Nov. 29, 2023

Disclaimer: The name of a student has been altered to protect their identity

One day during the midst of the pandemic, Mia Harris opened her laptop and logged into her scheduled Zoom consultation with a doctor. She had been struggling to maintain basic levels of attention and hoped to come away with some sort of verification of the symptoms she had been experiencing, ideally in the form of a diagnosis.

Instead, she was offered drugs.

“I essentially logged on to Zoom and proceeded to tell her I thought I had ADHD,” said Harris, now a senior at the University of Southern California. “Instead of asking me why I thought that, or running any diagnostic tests, she just proceeded to ask me if I wanted normal Adderall or Adderall XR.”

Adderall, the stimulant Harris was prescribed, is one of the most common forms of ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) medication. Along with other forms of prescription stimulants, and in large part amphetamines, it has become increasingly prevalent in recent years, barring a recent shortage.

The pandemic was a primary facilitator of this increase, particularly due to the rapid growth of telehealth at the beginning of the current decade.

Prescribing in the Pandemic

For as long as stimulants have been prescribed, individuals have attempted to obtain them using a variety of means, often through a process called malingering, or rather trying to feign a condition by faking or describing its symptoms. Yet during the pandemic, doing so successfully became a lot easier. What once was an in-depth consultation became a brief chat through a screen.

“As an ADHD clinician, we spend an hour to an hour and a half with a person trying to understand their history, to be able to get a good sense of what other conditions might explain ADHD,” said Dr. Kevin Anthsel, a professor of psychology at Syracuse University. “To do a telehealth appointment in 10 to 15 minutes and walk out with an ADHD [diagnosis], to me that’s concerning.”

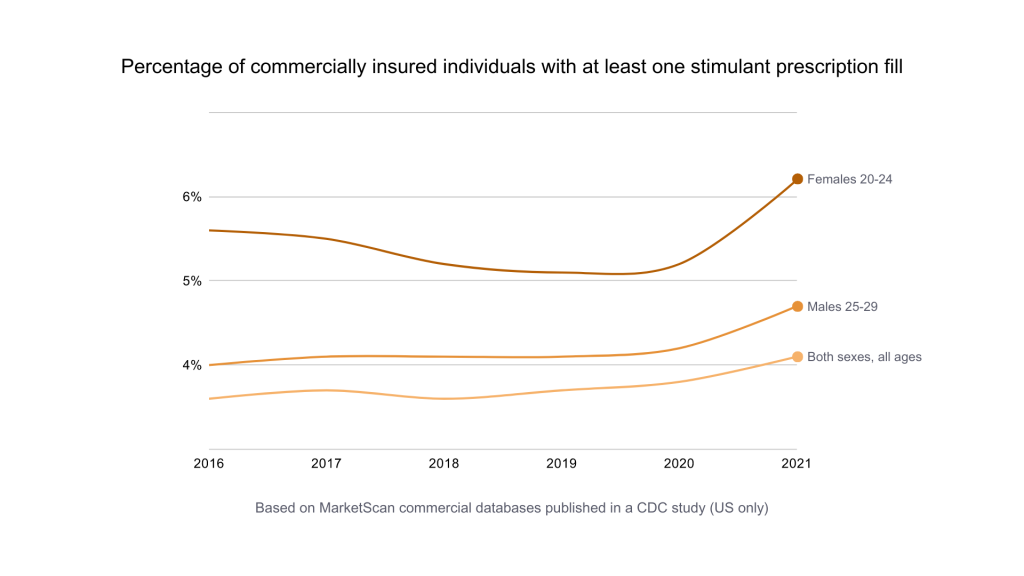

A study published by the CDC in March found that the percentage of commercially insured young adults (females between 15 and 44 and males between 25 and 44) with prescription stimulant fills increased by more than 10% between 2020 and 2021, during the early stages of the pandemic.

Compounding the issue is the fact that there is not a single test to identify ADHD, according to Dr. Terry Church, a professor at the USC School of Pharmacy.

“It’s my clinical judgment to decide if I want to give them a prescription or not,” said Dr. Church. “Nine times out of ten, if you if you tick off the right boxes, they’re going to default to providing the prescription.”

While some individuals misuse stimulants that they have been prescribed, this is not always the case. A significant portion of stimulant misusers are those who aren’t prescribed the drugs but obtain them through other means. A recent assessment conducted by the American College Health Association found that of a group of college students who had used a stimulant within three months, nearly two-thirds hadn’t done so on a prescription.

The issue isn’t isolated to college campuses, either. Another new study found that in certain middle and high schools across the country, as many as one in four students reported that they had abused ADHD medication.

‘Bottleneck of Need’

At their core, stimulants are meant to increase brain activity and help those with attention disorders like ADHD to better focus and stay alert. For those who need them, they can be a lifeline in keeping up with peers.

In 2022, the FDA declared a shortage of the ingredients used to manufacture Adderall. Shortly thereafter, other prescription stimulants like Ritalin and Concerta followed, and pharmacists found themselves amid a crisis. “It’s a hot mess everywhere you go,” said Dr. Kari Trotter Wall, the director of pharmacy at USC.

Though there is no official consensus, experts seem to believe that a multiplicity of factors led to the crisis, including the increase in prescriptions.

“There was such a such a proliferation of ADHD diagnoses being made during COVID that, actually, the pharmaceutical manufacturers were unable to keep up with demand, and we got into a shortage,” said Dr. Antshel.

Though pandemic-driven demand was certainly a key cause of the shortage of prescription stimulants, it was not the only one. Prescription numbers had been rising for years, and some of the large pharmaceutical companies that produce these drugs were facing labor shortages that led to understaffing, according to Dr. Church.

The shortage produced what Dr. Church described as a “bottleneck of need,” and led to downstream effects for recipients of the affected drugs. Finding the right stimulants became significantly harder both for patients and pharmacists.

“I feel like it’s turning into a full-time job for the average person that’s not a pharmacist,” said Dr. Trotter Wall. “The patient is now working for themselves, so to speak, when it used to be that we were working for you.”

Large numbers of students at USC were unable to obtain the drugs they needed and resorted to unorthodox methods, according to Dr. Trotter Wall, who painted a chaotic picture of the shortage.

Some students switched prescriptions, shifting from stimulant to stimulant until they found a drug that had any level of availability. Other students attempted to take matters into their own hands, and went back and forth in an ever-persistent game of telephone with doctors and pharmacies, hoping to land even a 30-day supply of a stimulant.

The pharmaceutical industry went into overdrive as it attempted to cope with the shortage, but students ultimately felt the impact.

“I feel horrible when I don’t have it and I can’t get it,” said Dr. Trotter Wall. “I know who’s in dire straits and who’s not, but we still remain first in, first out.”

The effect of the shortage was felt hardest by those with attention deficit disorders who rely on stimulants to get through their daily work. Yet, there is another category of people, particularly among student populations, that may not need to use stimulants quite as much.

These users, who either have no symptoms or mild symptoms of such disorders, begin to fall into the category of stimulant misusers.

‘Talking Themselves Into an Outcome’

The misconception at the core of the college stimulant misuse crisis is that no matter the circumstances, students believe that stimulants will improve academic performance, according to Richard Lucey, a senior prevention program manager at the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.

“Students who have non-medically misused a prescription stimulant, has it helped them get a better grade? To date, there’s been no large-scale research to show that that’s the case,” said Lucey.

Some experts, like Dr. Antshel, have actually linked the non-medical misuse of prescription stimulants with a potential negative impact on academic performance. Dr. Antshel said that students try to “talk themselves into an outcome that they want to happen,” though the data tends to say otherwise.

The issue is most rampant on college campuses, where stimulants are misused at much higher rates than elsewhere.

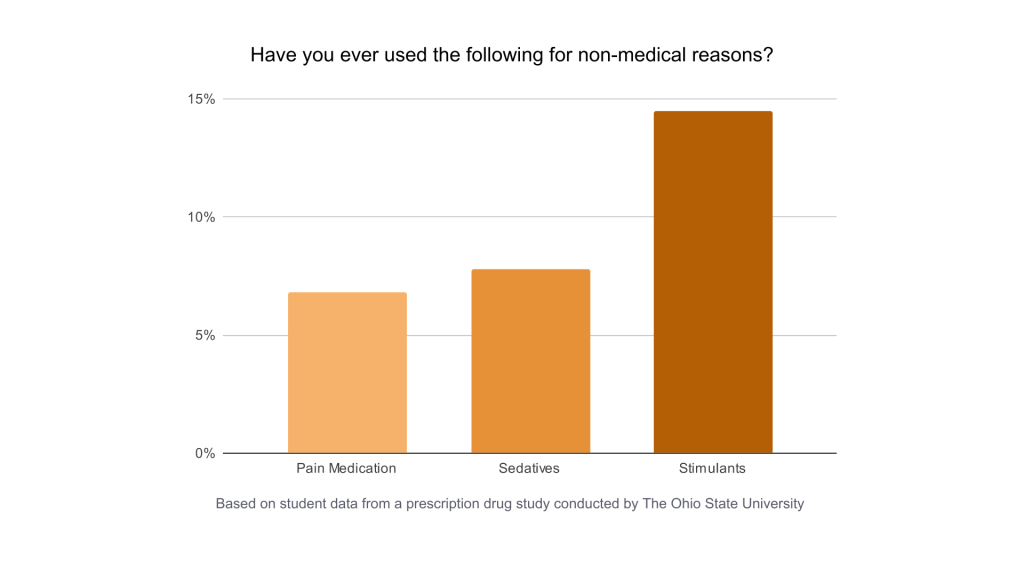

In the general population, the three most prominent categories of prescription drugs that are misused are opioids, sedatives, and stimulants, from most to least prevalent. Yet according to Lucey, on college campuses, this order inverts. Stimulants are generally the category of prescription drug most misused among university students, according to Lucey.

One of the primary reasons why stimulants are misused more on college campuses is that they are incredibly easy to access.

Oftentimes, students with stimulants tend not to completely use up their supply, and maintain a sort of “cache” of extra medication, according to Dr. Antshel. Students, who have a newfound sense of independence, can misuse these extra pills themselves, or give them away to friends.

“You can tell when it’s happening on campus,” said Dr. Church. “It’s usually around midterm season and then again around finals, where students who have the prescription who might be managing their disease perfectly well, and might need a little cash, will start diverting some of their prescription to students who don’t need it.”

Students also misuse stimulants in part due to academic pressure.

Today, according to Dr. Antshel, levels of perfectionism are at all-time highs in student populations. This extra weight could be driving students towards drugs that they think will boost their academic achievement.

And the perceptions regarding stimulants only further contribute to their misuse in higher education. Not only do students tend to believe that non-medical use of stimulants will improve their long-term academic performance, but students also seem to overestimate how many of their peers are using the drugs.

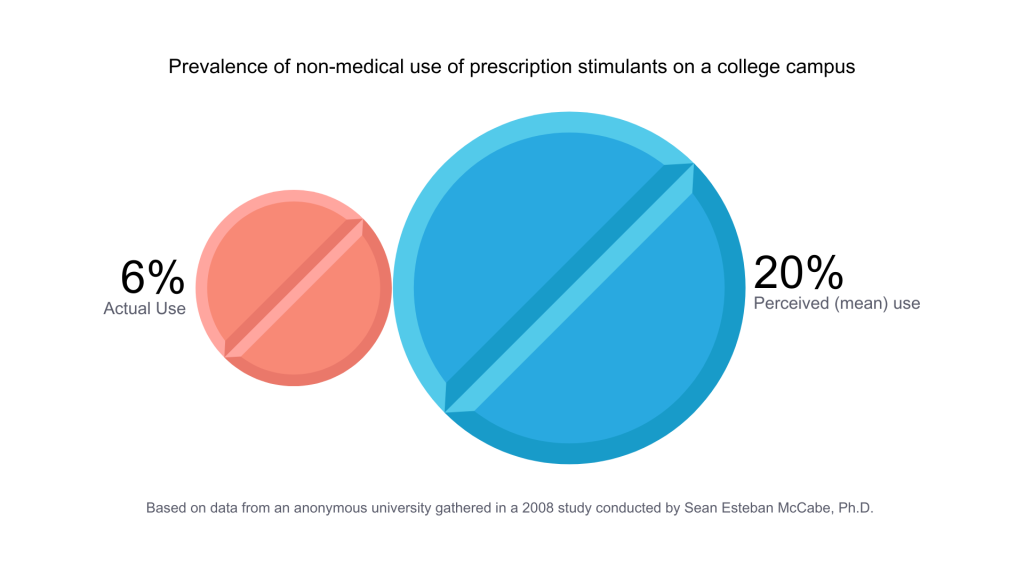

While research in this area is somewhat limited, a 2008 study determined that within a specific university, students on average believed that 20% of a student population participated in the non-medical use of stimulants, when the actual figure was more than three times less.

‘A Dark Side’

The impacts of the non-medical use of prescription stimulants extend far beyond their academic outcomes. While stimulants in general tend to be much safer than other categories of misused prescription drugs, they can still have detrimental physical and emotional effects, including addiction.

“You have these long periods where you’re not sleeping,” said Dr. Church. “You might not be eating very well. Weight fluctuates among these individuals. They have periods of intense activity followed by intense laziness.”

Stimulants can leave users feeling gray, dull, or even nervous when coming off of the substance. According to Dr. Church, activities that are performed while under the influence of a stimulant can become increasingly difficult to do or enjoy without the drug, which can ultimately lead to a form of psychological reliance and addiction.

This reliance often persists as misuse after college, according to Dr. Anthsel, who said that a large percentage of students tend to retain their non-medical stimulant habits post-graduation. The misuse of stimulants is also often “associated with risk for misuse of other substances,” according to Dr. Antshel.

‘Peer to Peer’

Efforts to decrease the ongoing misuse of stimulants range widely, but experts tend to want to focus more heavily on preventative measures than remedial ones.

Some experts, like Dr. Antshel, have taken issue with the way that certain institutions have handled the issue. “Some schools have taken to making stimulant misuse and honor code violation,” said Dr. Anthsel.

The worry, according to Dr. Antshel, is that this categorization outlines misuse as a form of cheating, and lumps it in with activities that – when successful – will improve an academic outcome. According to Dr. Antshel, “the outcomes for stimulant misuse are not in the direction that they’re likely to be considered as helpful.”

According to Dr. Church, education needs to be a central part of any successful preventative program.

“There needs to be honest conversation,” said Dr. Church. “That conversation can’t come from a professor like me. It can’t come from a physician. It can’t come from someone at the manufacturing site. It needs to be peer to peer.”