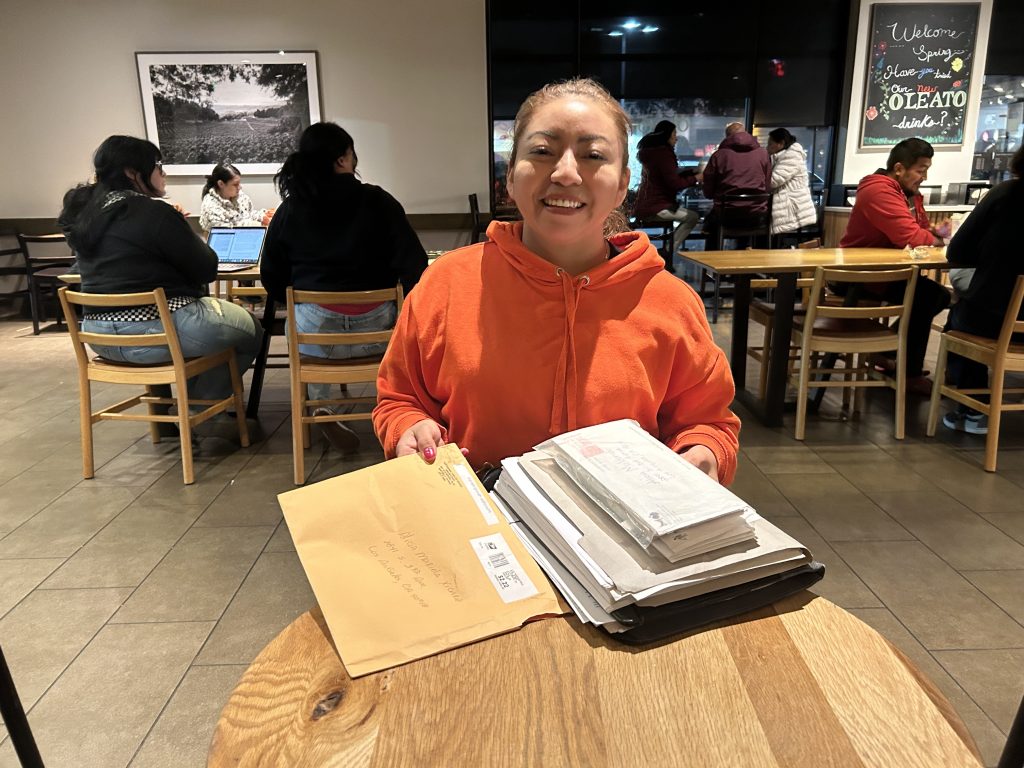

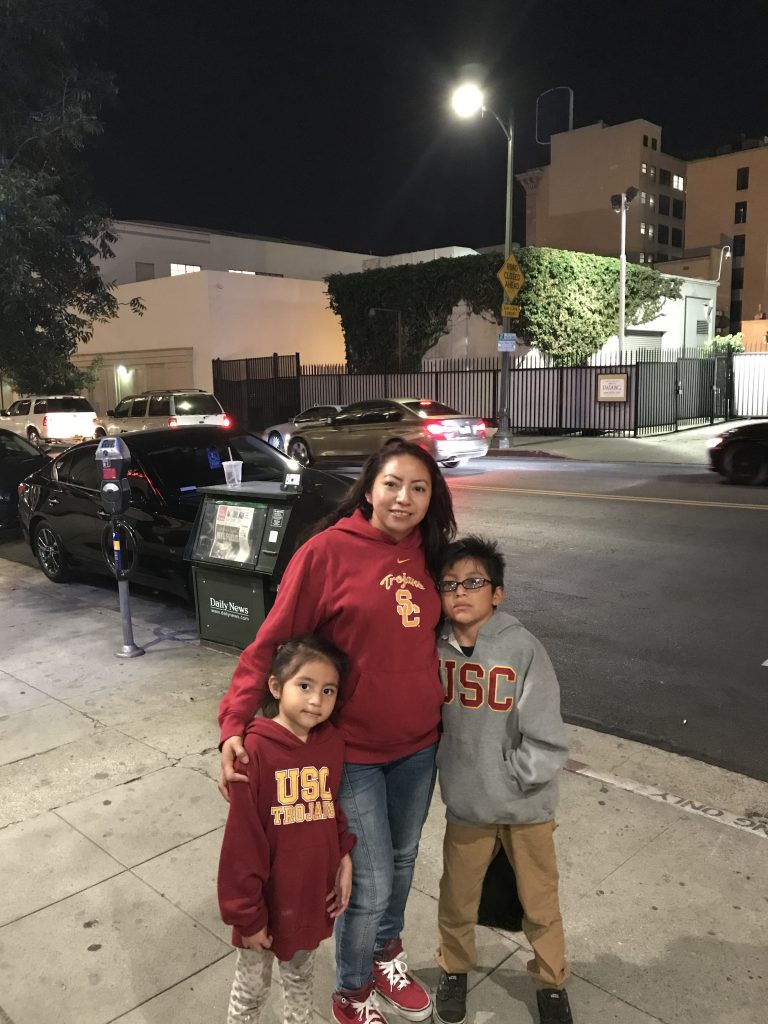

It was Aug. 2021, and Alicia Maldonado, a single mother of three and housekeeper who lives near USC, knew she wasn’t going to be able to pay her rent on time. Her kids — aged 17, 13 and 9 — had just tested positive for coronavirus, and without any family in the area, she took time off work to care for them.

Maldonado texted her landlord to let her know that her September rent payment would be late, and the landlord replied back that it was fine. But despite her assurances, Maldonado, who pays $950 a month for a one-bedroom apartment she’s lived in for 20 years, ended up facing eviction for that month’s rent.

Since Maldonado did not have an easy way to make up her missed income, she applied for a Covid Rent Relief Program and got the money approved. However, using her late payment as justification, her landlord didn’t accept the money approved by rent relief. Come November, Maldonado, whose apartment is rent-stabilized, found a “3 day notice to pay rent or quit” on her door, then soon afterwards an eviction summons.

With only five days to respond to the summons, Maldonado needed legal help quickly — and she found support with a lawyer from Legal Aid who represented her in court (having a lawyer defending a tenant in an eviction trial is rare, but the organization Stay Housed LA represents some clients).

During the trial at Stanley Mosk Courthouse in Downtown LA, Maldonado showed the judge text messages that demonstrated her landlord approved the late September payment. Since Maldonado had all the money to pay at that point, the judge told them to come to a settlement; the landlord agreed to accept Maldonado’s money, and the eviction case ended.

“I showed all my proof that I was enrolled in the program, and finally she [had] to accept [my payment],” Maldonado said. “In another way, maybe this time I [could have been] homeless with my kids. That’s why I think the program really supported me.”

Her landlord’s attempts to evict her didn’t stop there.

The Early Days of the Pandemic

Stories like Maldonado’s come during an increased push for tenant protections in light of the pandemic, rising homelessness and increasing rent costs. As the pandemic descended upon Los Angeles, the City feared total economic devastation. People would lose their jobs and be evicted from their homes, joining thousands of homeless residents already at greater risk of spreading the virus.

So the City acted fast, implementing eviction moratoriums, rent-relief programs and barring landlords from charging late fees on March 17, 2020. For the most part, it seems like these protections — at least in the immediate term — worked. Landlords still evicted people, but the catastrophic vision of a massive increase in homelessness never materialized.

However, John Pollock, the coordinator of National Coalition for Civil Rights Council, said that in many parts of the country there were “humongous enforcement problems” of the additional coronavirus tenant protections.

“The landlords, in some cases, just simply acted like those laws weren’t there,” he said. “And the courts were not acting as gatekeepers to ensure that the law was being followed.”

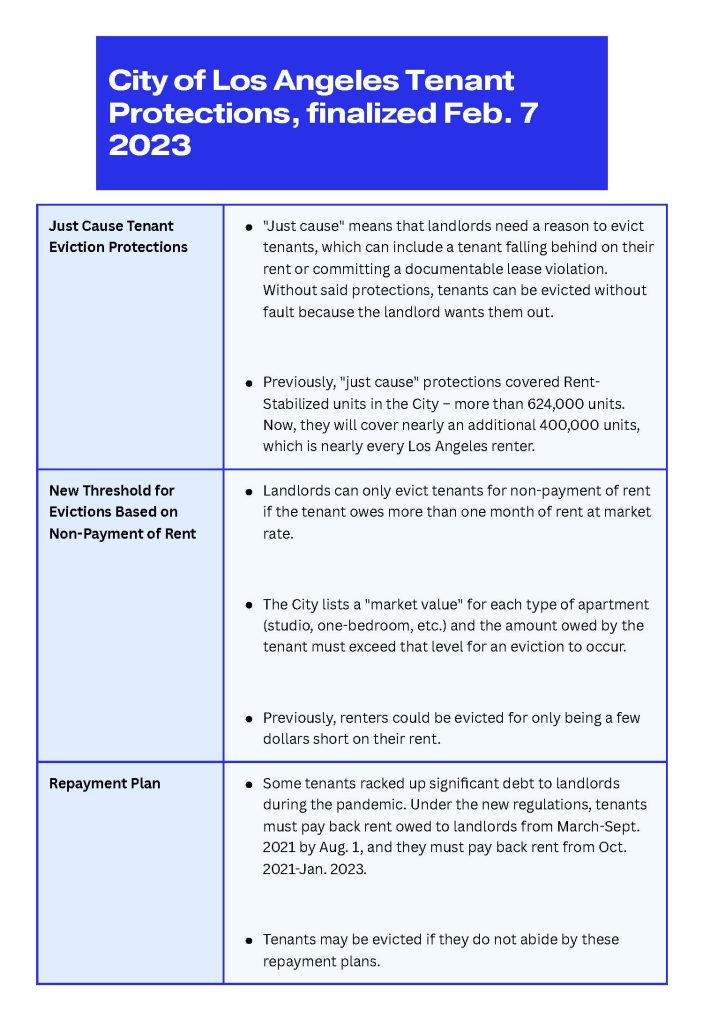

After multiple extensions, and after similar emergency protections had long expired in cities across the country, the protections were slated to finally end in February, 2023. But a week before the deadline on Jan. 20, the City Council made permanent many of the protections enacted during the emergency period, a potentially sweeping change to the City’s rental market.

What are the new tenant protections?

The new rules break down into three parts: first, there’s a just-cause rule — a requirement that states tenants can only be evicted for non-payment of rent or a “documentable lease violation.” In the past, tenants in many units could be evicted when an owner decided on it without a specific reason.

Second, tenants must now be behind more than one month of market-value rent to be evicted. If tenants are less than one month late on rent, the landlord cannot evict them. Had this rule been in place for Maldonado, she would not have faced eviction after her September rent was late.

Third, tenants have until Feb. 1, 2024 to pay back rent owed during the pandemic — and landlords will need to pay tenants relocation assistance if they raise rents more than 5% plus the inflation rate (a maximum of 10%).

These specific protections only apply to the City, and the County — as well as cities throughout it — have all had their own patchwork protections, varying in strength by place. The County’s coronavirus eviction protections expired Apr. 1, 2023.

Proponents of the new protections such as City Councilmember Nithya Raman praised the City’s ordinances as “the most significant since the institution of the Rent Stabilization Ordinance.”

Others, such as the California Apartments Association, said that the new rules unfairly burden landlords and add unneeded bureaucracy to the housing sector—ultimately hurting tenants by driving up rents.

Just-cause provisions work in theory, said Fred Sutton, Senior Vice President of Local Public Affairs of the California Apartments Association. In practice, however, he argued that most evictions are “just cause.” These specific provisions simply allow tenant attorneys to extend the eviction process because proving lease violations are difficult, Sutton said.

In interviews, landlords have said that they’ve faced challenges with tenants, specifically regarding evictions.

Javonna Wright, a landlord in South Los Angeles, owns five houses and has six tenants. While she’s had good experiences renting her places, there have been times where tenants have “destroyed [her] property – thousands and thousands of dollars.”

“The landlord is depending on the tenant to pay the mortgage … I can go to court, but what is the probability of me collecting that rent? I can get a judgment,” she said. “What does that mean? Nothing, if they don’t have the money to pay it.”

On the other hand, interviews with tenants have shown tenant protections’ ability to keep people housed.

After being evicted twice and experiencing homelessness, Dennis, who lives about a mile from USC and is using only his first name due to fear of retaliation, found a stable shared apartment through the unemployment office and his disability payments. However, during the pandemic, he encountered a unique problem that would put his new home at risk.

For the past three years, he had been feeding three stray cats out of a little cathouse that he built in his front yard — and one of them had just gotten pregnant. All of the sudden, there was a litter of 20 cats that came to his yard for food, and his landlord was threatening to evict him for having them on his property.

“One week, she said ‘Get them out of here by Friday or I’m gonna evict you,’ so I’m supposed to get rid of all these cats with nowhere to send them,” Dennis said.

Since Dennis has been evicted before, he knows that landlords cannot just evict him without going through a formal process. So he checked out the website for Los Angeles City rental ordinances and found that because of coronavirus tenant protections, landlords could not evict tenants for having unauthorized pets.

As soon as he told his landlord about that rule, she stopped threatening him and left him alone; Dennis was safe in his home and, on his own, decided to “get the cat population down to four or five.”

Relationships between tenants and landlords

While Sutton and some landlords spoke about the need for tenants to live up to their end of the bargain and pay rent in full, interviews with tenants suggest that landlords also often do not live up to their end of the bargain.

Brandon Stewart was a month into his lease when he first noticed something awry, as water began leaking through the ceiling and soaking the dining room table. The landlord dismissed all complaints until Stewart, who is 34 and lives in Jefferson Park, showed him a video of his soaked dining room table — and he began patching up the holes.

A few months later in June 2021, amid additional leaks, Stewart — an Amazon Marketing Manager — found a loaf of bread with a hole in its packaging. That marked the beginning of what Stewart called a “nightmare”: a months-long battle against rats and other vermin in his apartment with minimal help from his landlord, all while he and his brother continued to pay the full rent.

“I could hear them running upstairs in the roof, like in the attic area,” Stewart said. “And when I say running, I had a ceiling fan — and the ceiling fan would move.”

Greg Mayben, who lives near Downtown Los Angeles, said that he has been without heat this entire winter despite attempts to contact his landlord and the City. Another time, his landlord – after the building was sold – sent out a notice telling tenants that they needed to leave their apartments because of remodeling. Mayben knows he has rights, so he didn’t leave; but once he didn’t comply, the landlords stopped providing maintenance to the remaining tenants.

“We knew that as long as we paid our rent, they couldn’t evict us,” he said. “But from that moment on, we simply became invisible to them.”

His bathtub broke and water poured out of the wall for more than a week during a drought – and his landlord didn’t respond to his maintenance request. Mayben only had it fixed, and was only able to use his bathroom again, after threatening to call the media and asking the maintenance man for help directly rather than the landlord.

While he’s seen plenty of landlord misbehavior, Mayben said that with stronger laws for tenants during the pandemic, many people in his apartment building stopped paying rent and conditions worsened. Some tenants even dealt drugs within the building, he said. As regulations eased, those tenants started being evicted, half of Mayben’s building left and the problems went away, he said.

“There’s two sides, or multiple sides, to every story. Part of the issue during this moratorium of lack of eviction was: the purpose of the program to help protect people that really needed it. Unfortunately, as is always the case, you have people that take advantage,” Mayben said.

Some landlords, like Dorit Dowler-Guerrero, say they view renting out homes as something that can be a source of good in the world. Dowler-Guerrero owns more than five properties in the Los Angeles area that she rents out to veterans, tenants who have housing vouchers such as Section 8 and people at risk of homelessness.

With experience working in homelessness services and as a landlord, she supports tenants but sees both sides of the issue.

“The only real solution to homelessness is housing, housing and supportive services. The people we rent to who have vouchers, all have vouchers that are connected to social services, they get supportive services with them,” Dowler-Guerrero said.

Overall, she said, she is in favor of the City Council’s recent laws – as landlords should need a reason for eviction and tenants shouldn’t be evicted for pets they got during the pandemic nor unauthorized occupants. At the same time, she understands why some landlords are frustrated by the just-cause provision that requires a documentable lease violation for an eviction to occur.

“For example, you might not really have a definitive just cause that you can point to, but you have a nuisance tenant that really is bringing down the property and making you a bad neighbor,” Dowler-Guerrero said. “So I can understand why some landlords would be upset about needing to have just cause when sometimes there is no one thing to point out, but there’s just a really destructive tenant.”

No-Fault Eviction

At the same time, tenants face evictions without violating their leases or without owing rent.

In an old apartment in Echo Park, Erin, who is using only her first name for fear of retaliation, recently received a 60-day notice from her landlord. Erin doesn’t owe any rent and she hasn’t violated her lease, but she is facing an “owner move-in eviction,” meaning that the building owner aims to live in her unit. Weber, who has lived in the apartment for 11 years, is unsure of her future – and suspicious of the landlords’ explanation for her eviction.

“I’m just gonna try to do the best I can. I’m attending a lot of clinics and workshops, and I’m thinking about what I’m going to do. I mean, I’ve lived here for 11 years, so it’s going to take me a while to organize my stuff,” Erin said. “I have no place to go. I’m not going to rent another place – the rents are ridiculous.”

And for Maldonado, the challenges keep coming. In May, 2022, she faced another eviction – this time unrelated to rent payment; her landlord alleged that Maldonado did not allow her entry into the apartment for inspection. Once again, Maldonado sought legal help, went to court and won the case (her apartment has just-cause protections, so her landlord needed to show a documentable lease violation).

Throughout this whole process, and still to this day, Maldonado said she faces harassment from her landlord.

According to Maldonado, her trash can has long been broken and not fixed by her landlord, and her landlord has parked cars in the driveway in a way that makes it impossible for her to properly take out the trash. However, her landlord has threatened eviction due to her trash being unorganized. Maldonado also said her landlord has harassed her in other ways, such as sending people to needlessly enter her apartment, something that has scared her kids.

“My kids say ‘Mommy, I don’t wanna go to school,’ and I say they have to,” Maldonado said. “Then they say ‘[the landlord] can come and maybe she can close the door, and how would we be able to take everything out?’”

Alicia Maldonado

“My kids say ‘Mommy, I don’t wanna go to school,’ and I say they have to,” Maldonado said. “Then they say ‘[the landlord] can come and maybe she can close the door, and how would we be able to take everything out?’”

Now, Maldonado is once again facing eviction – this time because of her ex-husband, who she has a domestic violence restraining order against. Her husband still can see her kids some weekends, and on those days, Maldonado leaves – she has no contact with him. While he is on the apartment’s lease, he has not lived there for more than 2 years – something Maldonado’s landlord knows.

One weekend he was accused of assaulting and harassing Maldonado’s neighbors while visiting, and now Maldonado has received a three day notice for eviction because of the accusation against her husband. She has tried to still pay rent but had her checks sent back, so she is currently waiting for the eviction summons in order to start fighting the case.

“Maybe it’s time to take another place. But I don’t wanna get out like I did something wrong,” Maldonado said. “I don’t want my next landlords to say they kicked me out because I didn’t pay or something. I have paid my rent.”

Click on the other tabs to learn more about the eviction process, as well as how experts are thinking about the impact of eviction protections.