A hairpin curve at mile 11.

That is the exact location where runner Monica Hebner realized her identical twin, Isabel, was no longer trailing behind her shoulder.

The sisters had prepared to run the U.S. Olympic Marathon Team Trials in Orlando, Florida side by side. Thousands of miles of training, hundreds of hours of recovery, countless carbohydrates, and decorated collegiate cross-country careers led them to the starting line in which a trip to the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris was a properly paced 26.2 miles away.

After a sub six-minute mile to start the run, an irregular step during mile two derailed Isabel’s race — and affected the twins’ hope for a joint work trip to France.

“That feels wrong,” Isabel told her sister, “but nothing hurts. I’m fine.”

Despite the drive to persevere in a moment of adversity, the irregular step led to a stress fracture in her foot that made the 5:59 marathon pace fall apart, and by mile seven, the seemingly inseparable twins were separated.

But the separation only lasted four miles. At mile 11, an already emotionally drained Monica stepped off as well. If it wasn’t going to be both of them, she decided, it was going to be neither of them.

Running, whether track or cross-country, is often an individual calling. It can be a runner against a clock, a runner against a course, or a runner against their own self. While the larger goal is to defeat opponents, most runners will tell you a personal record is more gratifying than any sort of competitive win.

Individuality aside, it’s interpersonal relationships that often push world-class athletes to not only their peak as Olympic performers, but also as humans. Although all interpersonal relationships hold value, there are unique properties in the ones that can be categorized as intra-family. Whether it be a relationship between twins, an older and younger sibling, a parent and their child, or even two friends who are close enough to call one another brothers, a story lies within the bond.

In modern sports, there is no shortage of prominent sibling pros: Peyton and Eli Manning, Jason and Travis Kelce, and John and Jim Harbaugh.

As for the Olympics, they have welcomed Serena and Venus Williams who have both won four gold medals in women’s tennis, Bob and Mike Bryan who have collectively won one gold medal in men’s tennis, and Pau and Marc Gasol have won two silver medals and a bronze medal in men’s basketball.

While the trophies and medals may be what spectators most often remember, the relationships and intra-family bonds that are strengthened — or weakened — on the road toward success is often where the most poignant stories lie.

Famous Olympic Siblings of the 21st Century

Competing Sisters —‘Where Is She?’

The city of Orlando “was running nerd Mecca,” said Isabel Hebner. Masses of people lined the streets to see who’d represent the United States in the summer 2024 Olympic Games. With high humidity and scorching hot pavement, one would not say Orlando was the perfect environment for such a high stakes race, but to the Hebner twins, who train in the heat of Austin, Texas, it felt like just another race day.

“To be in a race with every man and woman that you looked up to throughout your running career, all at the same starting line, was something that was super unbelievably cool,” said Monica.

Although the race was packed with some of the country’s most prominent distance runners, the Hebners’ road to the starting line on North Rosalind Avenue didn’t come easily, or directly.

“It felt like a once in a lifetime experience, but I hope it’s not a once in a lifetime experience. I hope it’s the first of my lifetime,” said Monica.

Upon entering Northern Highlands Regional High School in Allendale, New Jersey as teenagers, the twins were avid lacrosse players. Like many other distance runners, they started doing cross-country after a coach tried to persuade them to stay in shape for the lacrosse season.

When looking for an activity to participate in during the fall season, Monica immediately showed interest in field hockey, a sport in which Northern Highlands consistently ranks among the best in the state. By nature, Isabel wanted nothing to do with field hockey, she wanted to give cross-country running a shot. After a bit of convincing, Monica succumbed to her twin’s pressure and decided to run with her sister.

A rather small decision in the moment eventually led them to quit lacrosse, the sport they once called their favorite, and focus all of their attention towards distance running. After four seasons of varsity cross-country, and indoor and outdoor track, the twins both received state and national recognition for their running abilities.

The conclusion of high school marked the first time that both sisters went their separate ways in their sporting careers. Monica went on to run at Duke her freshman season, then at UCLA for the rest of her undergraduate career, before moving to the University of Texas at Austin for her season as a graduate student. Isabel spent her freshman season at the University of Pennsylvania before transferring to the University of Texas at Austin for her time as an undergraduate and graduate student. The years apart brought them greater independence.

“Growing up running together made us the athletes we are,” said Monica. “But going to college separately was also super helpful because aside from being athletes, we got to be our own people. For the first time we weren’t ‘the twins,’ we were Monica and Isabel.”

Despite ‘the twins’ identity fading during their collegiate careers, grappling between being competitors, having raced against one another since high school, while simultaneously being teammates throughout their entire training regime, persists in the minds of both sisters to this day.

After finishing their graduate degrees in 2023, and beginning their professional careers, the urge to compete never seemed to fade away. Monica now works as a Business Consultant at FTI Consulting, and Isabel works as an Investment Banking Analyst at TD Securities. While the 24-year-olds live their own separate lives, the bond that track and cross-country has provided them has allowed the two to remain close.

“When we started training for marathons, it changed very much to teammates. I think in college we were definitely competing against each other,” said Isabel. “In college, while we were teammates, I was always racing Monica. I was always looking for her. ‘Where is she?’”

Many people may often let a younger or older sibling win. Whether it’s playing basketball in the driveway, knee hockey in the basement, or Connect 4 on the kitchen table, there’s sometimes that faint voice saying, “Maybe they can have this win.” But for the Hebners, the competitive drive to win seemingly always overpowered their ability to concede.

“I could tell by the way she breathes, I know if she’s about to come hunt me down, and I’m always like ‘no way in hell is that going to happen,’” said Monica.

Raceday in Orlando

The idea of trying to qualify for the Olympic marathon wasn’t an obvious proposal.

“It was Monica’s crazy idea,” said Isabel. “But I wasn’t going to let her do it alone. If she was going to do it I was also going to do it.”

80 mile weeks, long days in the Austin heat, and a qualifying time at the McKirdy Micro Marathon in Rockland County, New York led them to the starting line in Orlando.

As bystanders and supporters lined the streets, a jubilant start to the race for both twins, mostly powered by adrenaline, quickly went south after Isabel’s stress fracture.

The immediate goal was to simply get out of the downtown area. She wanted to let the crowd simmer down and the adrenaline to disappear. She figured that once she got to the six mile mark she’d be more capable of determining what was truly going on with her foot.

At mile seven Isabel stepped off, she could go no further. A possible trip to France was no more because of a tiny crack in her foot.

Monica had no idea what was going on behind her. Not being able to hear Isabel’s breathing made things suspect from the get go, but to her it was simply another race, just one where her twin was maybe not as visible in her peripheral vision.

“It was so loud. I can tell by her breathing when she’s next to me, but I could not hear her from the start, so I never knew she fell off the pace,” said Monica. “So I did this hairpin turn at mile 11, I saw the person in last place and saw no sign of Isabel. That’s when I knew she must have stepped off.”

Contrary to how the journey of Olympic marathon running began, this time it was Monica who made a sacrifice for Isabel. “I decided I was going to stop when I didn’t see her at the hairpin turn,” said Monica. “I didn’t want to do this by myself.”

While she did cite Isabel’s injury as one of the reasons why she chose not to continue, even Monica herself appeared to not be entirely sure why exactly she stopped. It could have been guilt, sadness, possibly physical fatigue, or maybe it was just an instinct.

The two may be twins, but it’s Isabel who’s older by two minutes, and like a true younger sibling, Monica did not want to go forward without her older counterpart.

The two together could have been consumed by this great sense of failure, but they chose otherwise. Everyone hates losing, or in the case of a runner, not finishing, but there was a specific sense of pride the twins took in this journey of both sisterhood and marathon training. While they won’t be at the Paris Olympics, the sisters have a plan. If they can find the drive, determination and sisterly motivation, the goal is to be sharing the podium and winning medals at the 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

The Brother and Sister Duo

Deaths, breakups, friendship problems.

Stress, chronic exhaustion, and insomnia.

Anna Benedettini, another participant in the 2024 Olympic Marathon Trials, lived this nightmarish scenario every day during her time as a member of the University of Michigan cross-country team.

Upon arrival in Ann Arbor everything was great, but after the initial few months a rather stable career of Anna’s was completely flipped upside down.

“It was just a six to eight month span that no 20 year old should have to go through,” said Benedettini.

As a runner, or as any athlete, if you’re not properly recovering then your body will feel the consequences. The stress, exhaustion, and insomnia that were by-products of the ongoing challenges in her life were not allowing her body to heal from the extensive training she was actively doing.

This resulted in countless stress fractures in her feet and shins, which completely derailed her collegiate career.

When faced with such adversity it’s fair to say that many people in college often turn to things that could worsen their problems — extensive partying, drinking, or maybe drugs.

But Benedettini turned to Waco, Texas, and her older brother, Jordan.

Due to their differing genders and ages the two have never run against each other in an organized race. Still, as siblings, they have been there for one another at every step along the journey of life. For Anna, that journey began in middle school.

“Growing up I had no aspirations to do well in school or sports, that was so out of my realm,” said Benedettini. “At the end of middle school, my parents sat me down and told me I had to do something with my life.”

Viewed as the odd one out, due to her parents running in college and her brother being a superstar soccer player and runner at their high school, she eventually became content with giving something a go. Logistically, high school cross-country made the most sense, and it only took one practice for Benedettini to realize she made a great decision.

“I started going to practice, and I loved it. I loved putting in a lot of effort and getting immediate results, because never in my life had I tried for something and then been successful at it,” said Benedettini.

Logistically, cross-country made the most sense because after every practice she’d have a ride home. The ride would come from her brother, Jordan, who was a Senior on the team at the time.

Every car ride home was viewed as a debrief of that day’s practice. Whether it was the goods and the bads or the rights and the wrongs, everything was talked about. But regardless, from day one, Jordan always looked to instill one thing in Anna, and that was confidence.

“I’m seeing you in practice, and I think you could be really great,” Jordan would say. And for Anna, that’s all she needed.

Jordan went on to run cross-country and track at Baylor University, and after graduating high school Anna joined him. After immediate success at Baylor, Benedettini’s desire to be a part of a more successful program took over. She was running so fast that Baylor’s roster no longer had anyone she could practice with, so as a result she transferred to the University of Michigan.

At the conclusion of a rather challenging collegiate career at Michigan, one of Benedettini’s main goals was to find joy in running again, and the one person she looked to was Jordan. Jordan, who still resides in Waco, Texas became Anna’s pacer, a role that essentially allows Anna to run without using her mind or intuition.

Anna, who moved to Austin after graduation, would spend weekends doing long runs in Waco. “Most weekends, people in Austin would go crazy and go out and party, but I would drive to Waco to hang out with Jordan,” said Anna. “I would go up Friday, run with him one day, long run with him the other day, and drive back Sunday night. We just had that bond. Whether we were doing a workout, an easy run, or anything, it was so enjoyable to me, it was such an escape.”

Despite pacing Anna throughout training, the two have only run one marathon together. Similar to the Hebners, that was the McKirdy Micro Marathon in New York this past October in which Anna OTQ’d (Olympic Training Qualified), allowing her to run in Orlando.

The bond, which they consider to be unbreakable, is one you can see not only off the course but also on the course.

“I accidentally clipped the back of his foot, because I like to run very close to the back of the person in front of me, and every time he’d pretend to pull a muscle,” said Anna. “He was also trying to do something dramatic to make me laugh.”

After completely outpacing themselves in New York, the two found themselves two miles away from the finish line with plenty of time to spare. “He looked down at his watch. And he’s like we could run so slow right now. And you’re still gonna qualify for the Olympic trials,” said Anna. “So we spent that next lap just laughing, and telling stories.”

Despite a failed attempt in Orlando to qualify for Paris, Anna, like many young emerging distance runners, has her eyes set on Los Angeles in 2028. Although this time around, in addition to looking out for herself, she also hopes to help Jordan complete his goal of running in the 2028 men’s olympic trials as well.

Bonded by Experience

“I think Norman will be a bit disappointed and he has become a tad hit or miss over the last twelve months,” said members of the nationally televised Olympic broadcast team.

These words echoed throughout households in the early hours of August 5th, 2021.

That is the day when Michael Norman, who was labeled as a rising star in the track community at the time, finished fifth in the men’s 400m dash at the 2020 Olympic games.

Outside of blood relatives, camaraderie can lie anywhere. There are friends, romantic partners, or even work colleagues.

But there are also training partners. A term in which even those who identify as such aren’t sure if they’re competitors or teammates. A term that is universally known. There is no direct relationship connecting the two people, but they know everything about one another. They see all the highs and all the lows. All the good reps and all the bad reps.

Michael Norman, a World Champion and Olympic gold medalist, has a massive support system. Every time he steps foot on the track to run the 400m dash he has coaches, trainers, friends, nutritionists, and an entire country standing behind him.

On the surface, world class athletes seem hyper independent. Norman has a heavily tailored weekly training regime on the track, individualized weight training routines, and notebooks filled with his daily macro and micronutrients. The seemingly large team of people helping him succeed drastically shrinks when the starter pistol goes off, and the only person there to help him become victorious is himself.

Despite the ability to rely heavily on oneself, in the face of adversity there isn’t much that is more helpful than a familiar face to look to.

For Norman, that initial wave of adversity came during the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo.

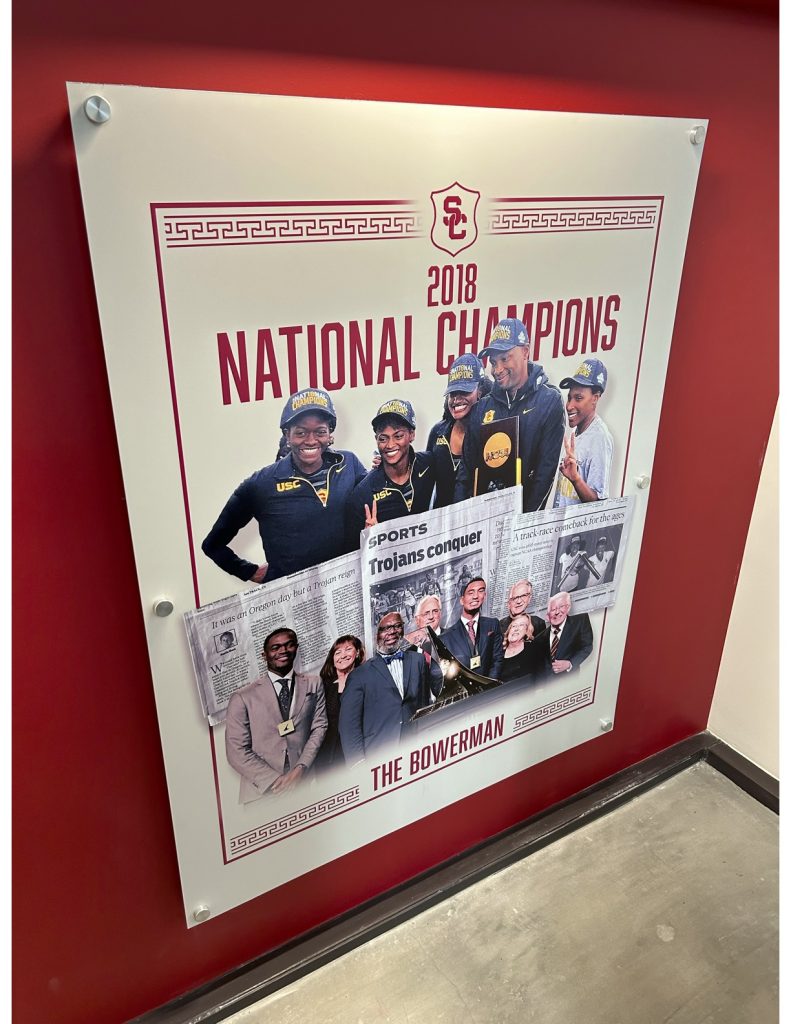

After a collegiate career that finished with him winning The Bowerman, the award given to the country’s best performing track and field athlete, Norman turned his attention to a professional career. Early success provided him the opportunity to compete for Team USA in the 2020 Olympics. Norman, who has great versatility as a track athlete, planned on competing in the 400m dash and the 400m relay.

The up and coming young star was the heavy favorite for the 400m dash, but after a shocking performance ended up finishing fifth.

“It was a pretty challenging time,” said Norman. “You start the year with high goals and high expectations for yourself, but going in as the favorite and underperforming hits deep. We spend so much time dedicated to the sport, so when you fall short of your expectations, and you know you can do better, it’s devastating.”

From the get go, Norman was filled with unknowns. After being assigned the eighth lane, one of the hardest lanes to win from, he didn’t know how good he was going to do and he didn’t even know how good of shape he was in. All he could do was hope for the best.

“There wasn’t any real confidence behind my running that season, and unfortunately, that ended up being a huge factor,” said Norman.

Immediately after the loss, Norman felt immense feelings of devastation and frustration. Losing aside, the incentive based sport would most definitely have its own consequences. Brand deals, salaries, and livelihoods would all be affected.

Despite his individual loss, Norman went on to win gold in the 400m relay with his three teammates, one of which is most notably Rye Benjamin.

Norman and Benjamin are self proclaimed best friends. The relationship between the two dates back to when they raced together at USC, and has continued to this day where they still train together.

After Norman’s 2020 Olympic loss, he refocused in hopes to get redemption at the 2022 World Championships. “I was very laser focused on getting back to where I wanted to be as an athlete. I used the frustration and disappointment from the Olympics as my main fuel and motivation going into the next year,” said Norman.

Norman’s work ethic eventually led to a gold medal at the 2022 World Championships in the 400m race.

Norman credits this accomplishment to living his life by two mottos.

The first being, “If it’s not going to make me a champion, I’m not going to do it.”

The second being, “If it’s comfortable, it’s too easy.”

Outside of Norman’s tightly knit relationship with Benjamin, he also heavily relies on the relationship he has with his father. “I think the easiest person to talk to in those moments would probably be my dad just because I can freely talk to him with no filter,” said Norman. “I tend to lean on him and vent to get through the emotions, and the harder parts of life in general.”

Norman and Benjamin, the Nike sponsored athletes, can be seen doing their daily track workouts on USC’s campus, and their weekly weight training workouts in the John Mckay Center weight room. All their current preparation is in hopes to compete for Team USA in the 2024 Olympic Games.

As for Norman, he’s grateful to have such a strong relationship with his training partner. “He’s somebody that I can talk to when times get tough. He keeps my head leveled in frustrating moments,” said Norman. “We have the same mentality when it comes to working out and trying to achieve our goals, which is great because when track gets tough, it gets tough.”

On the pavement, within the white lines on the track, and in life in general gratifying results and happily ever afters are hard to come by. But despite the stoic persona put on by some of the world’s best athletes, they know that the road to personal fulfillment never has to be alone.