“Where do we go from here?“

It’s a question rooted not just in policy but in the daily calculus of survival, identity and visibility for transgender immigrants in the United States. These individuals navigate both physical and personal borders in a political climate increasingly hostile to both.

LOS ANGELES – “I don’t have the luxury of choosing a job that fulfills me,” said Brett Zhong, a transmasculine USC graduate holding on to his work visa through a job he openly dislikes. “This sponsorship is literally the only thing keeping me here.”

Just weeks earlier, on March 20, Albus Wang, a transfemme nonbinary artist and photographer who spent more than a decade building a life in Los Angeles, was forced to leave the United States after their visa expired.

“I knew this day would come eventually,” Wang said. “But facing the reality of being forced out hit me harder than I expected.”

Their stories echo across a growing number of transgender immigrants, whose lives are shaped by exclusionary policies and by the invisible weight of navigating systemic disbelief, fear, and erasure. The U.S. immigration system already demands compromise and endurance. For transgender immigrants, it demands even more: survival at the intersection of bureaucracy and identity, with no safety net in sight.

“Every siren, every unexpected knock at the door makes me freeze.”

Mayorga

Few understand these stakes more intimately than Mayorga, a transgender woman from El Salvador who works overnight cleaning commercial buildings in East Los Angeles. She asked to remain anonymous due to fear of deportation, but her voice is clear and direct.

“When the news came out that Trump’s executive order would cut funding for clinics offering care to trans people, I thought, what if the free clinic I rely on shuts down next week?” she said. “I don’t have a doctor. I don’t have insurance. All I have are people who whisper names of places where I can go and not get asked for papers.”

Before she found help, Mayorga said she bought hormones and silicone from strangers on the street. “You just ask around. Sometimes they give you a number. Sometimes they sell it right out of a bag. It’s not safe, but it’s what we had.”

One injection caused such severe swelling in her arm that she couldn’t move it for days. At a clinic, she fled as soon as they asked for ID.

“Every siren, every unexpected knock at the door makes me freeze,” Mayorga said.

Over the past four years, she has cycled through 10 employers. Most paid her in cash and offered no protections. Her survival strategy, she explained, often begins with walking into local stores and directly asking managers if they are willing to pay under the table.

“That way they know I’m undocumented,” she said. “But if they pay cash, they avoid taxes. That’s how I survive.”

The system remains unforgiving. Once, a manager overheard coworkers gossiping about her gender identity and fired her the next day. “He said I was too much drama,” Mayorga said.

Mayorga’s story is not unique. It reflects the precarious reality for thousands of undocumented transgender people in the United States, where access to jobs, health care and even physical safety is tied to fragile legal status.

According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, 29 percent of undocumented transgender individuals avoid medical care for fear of deportation — more than three times the rate of the general U.S. population. With estimates ranging from 15,000 to 50,000 undocumented transgender adults nationwide, many live in the shadows of systems that fail to protect them.

Some, like Albus Wang, were forced to leave entirely.

“I had no choice but to leave.”

Albus Wang

Wang spent more than a decade building a life in Los Angeles as a transfemme nonbinary artist and photographer. The city’s queer communities and creative spaces allowed them to explore gender and identity with a freedom that felt impossible in China.

But that freedom came with limits. When their H-1B work visa expired, Wang lost the legal right to stay. “I had no choice but to leave,” they said from their temporary residence in Thailand.

Just days before their departure, on March 9, 2025, Wang performed at the LALA Feminist Open Mic, speaking publicly about their gender and sexuality. “It felt like a rare moment where I was truly seen and safe,” they said. “The audience was supportive, and for a brief moment, I didn’t feel the pressure of my immigration status.”

Watch Albus Wang on Love, Gender, and the Pain of Liking Men | LALA Feminist Open Mic

Wang first arrived in the United States on a student visa and later enrolled in a cosmetology school to obtain a vocational visa. Each step provided only temporary protection. Eventually, they applied for an EB-5 visa, an investor-based path to permanent residency, but their application has been stalled for nearly eight years due to shifting policies and bureaucratic backlogs.

“I don’t even know if I’ll ever get approved,” Wang said. “And waiting wasn’t an option. I couldn’t just stay in the United States indefinitely with no status.”

While Wang’s journey was cut short by bureaucratic delay, Brett Zhong is still holding on — just barely.

“They don’t see me as a person. They see me as something to gawk at.”

Brett Zhong

A recent USC graduate with a degree in economics, Zhong currently lives in Los Angeles under Optional Practical Training, a temporary status that allows international students to work after graduation. His job moderating TikTok livestream sales offers no personal fulfillment, but it provides something he cannot afford to lose: visa sponsorship.

“It’s nearly impossible to find another company willing to sponsor a transgender immigrant,” Zhong said. “So I stay.”

Now, Zhong is preparing for the H-1B visa lottery, a system with low approval rates and little transparency.

“It’s not about qualifications,” he said. “It’s just luck. And that’s exhausting.”

Even at work, challenges persist. At a company gathering, Zhong was cornered by coworkers who asked, “Are you a T?” — a slang term in Chinese referring to a butch lesbian. He explained that he is transmasculine but was met with blank stares.

“So… you’re a T,” one of them repeated.

“They don’t see me as a person,” Zhong said. “They see me as something to gawk at.”

For Zhong, staying in the United States means accepting constant misrecognition, instability and the risk of invisibility. Leaving is not a real option either.

“I don’t have the privilege to find a perfect situation,” he said. “I’m just desperately clinging to anything that allows me to stay.”

Zhong’s experience of being reduced to a label, rather than seen as a person, resonates with Nevaeh Li, a transmasculine USC senior from China. For Li, misunderstanding runs deeper than workplace ignorance. It is tied to cultural expectations around gender, silence and who gets to be believed.

His transition across two countries has forced him to examine how others perceive him and how he has learned to perceive himself.

You can hear more of Li’s story in the podcast episode below, along with an Audiogram clip where he reflects on transitioning in China versus the U.S., and how not being questioned by American doctors felt both liberating and disorienting. He speaks about navigating language barriers, family expectations, and the quieter forms of gender policing that persist across borders.

Watch Audiogram Clip “Am I Trans Enough?” From Podcast Episode: From Silence to Self with Nevaeh Li

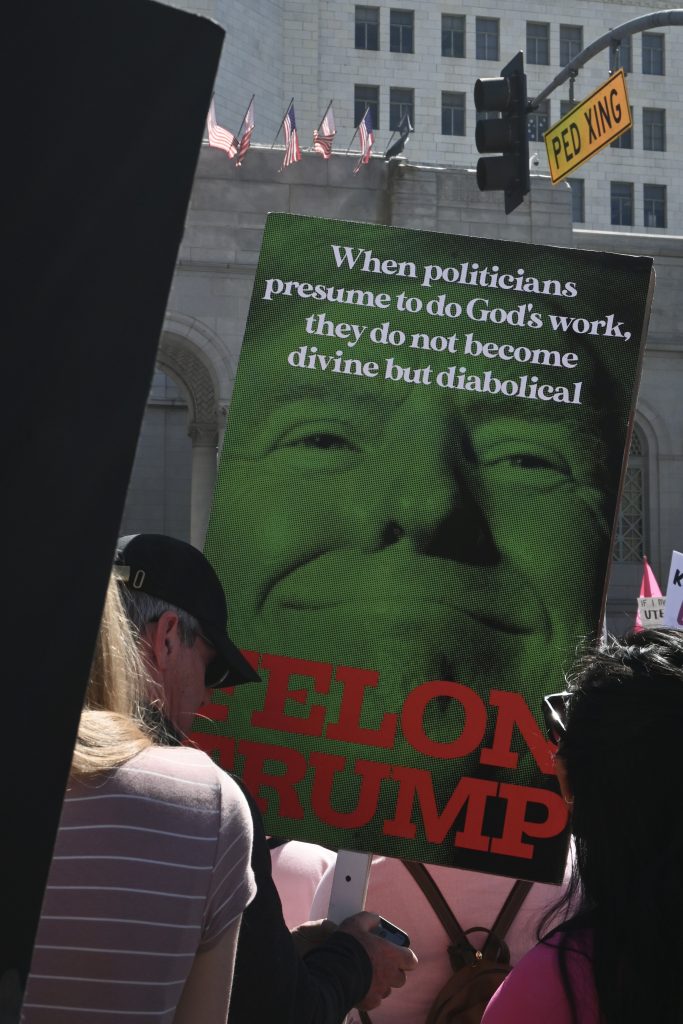

These stories reflect personal hardship and an increasingly hostile political environment. In his 2025 inaugural address, President Donald Trump declared, “There are only two genders: male and female,” a statement that set the tone for a wave of executive orders rolling back protections for transgender people.

Days later, he signed orders dismantling federal diversity, equity and inclusion programs, revoking recognition for nonbinary identities and labeling gender-affirming care for youth as potential child abuse.

At the same time, immigration policy grew more aggressive. “We will carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history,” Trump pledged during his campaign. That promise has since shaped policies targeting undocumented immigrants, including transgender people like Mayorga. Critics say these directives not only threaten civil rights — they institutionalize erasure.

“These policies don’t just sit on paper,” Mayorga said. “They travel all the way down to people like me. I lose jobs. I lose care. I lose sleep.”

The following timeline shows how, in just a few months, a series of federal actions reshaped the lives of transgender immigrants and turned political rhetoric into daily obstacles for survival.

Even within LGBTQ spaces, transgender immigrants often encounter exclusion. Bella Pritzkat, a transgender woman who serves as senior manager of activities at the Los Angeles LGBT Center and as a peer support specialist at Painted Brain, has seen it firsthand.

At the center, she leads support groups under the Trans* Lounge program, where she has helped newly arrived transgender immigrants find community, resources and language access.

“A lot of folks come in with trauma. Not just from their home country, but from trying to survive in the United States with no papers, no hormones and no support,” she said. “We connect them to legal aid, but more than anything, we make sure they’re not isolated.”

Still, she says queer spaces are not immune to gatekeeping.

“There was pushback from some older gay men about having trans men or transmasculine people in their support meetings,” she recalled. “Luckily, I’m the one running them. So I said, Too bad. Everyone stays.”

Through both her roles, Pritzkat sees a common pattern.

“The system pushes people out,” she said. “And if we’re not careful, even our own community starts doing the same. That’s what I fight against every day.”

While grassroots support is vital, broader structural change demands organized advocacy. Few embody that fight more than Bamby Salcedo, founder and president of the TransLatin@ Coalition.

“I turned that pain into something bigger than me.”

Bamby Salcedo

A longtime activist and formerly undocumented transgender woman, Salcedo began her work after surviving abuse and detention in immigration custody.

“I was treated like I wasn’t human,” she has said in public talks. “But I turned that pain into something bigger than me.”

Under her leadership, the TransLatin@ Coalition has expanded rapidly. In 2024 alone, it opened new centers in El Monte and Orange County, expanded its Hollywood headquarters and provided more than 11,000 services, ranging from legal aid and ID document changes to transitional housing and HIV care.

“These are not handouts,” Salcedo said at a recent event. “They are life-saving interventions for people who have been systematically erased.”

The erasure she refers to is legal. As executive orders accumulate, organizations like the TransLatin@ Coalition and the Transgender Law Center have stepped in where state and federal systems have failed.

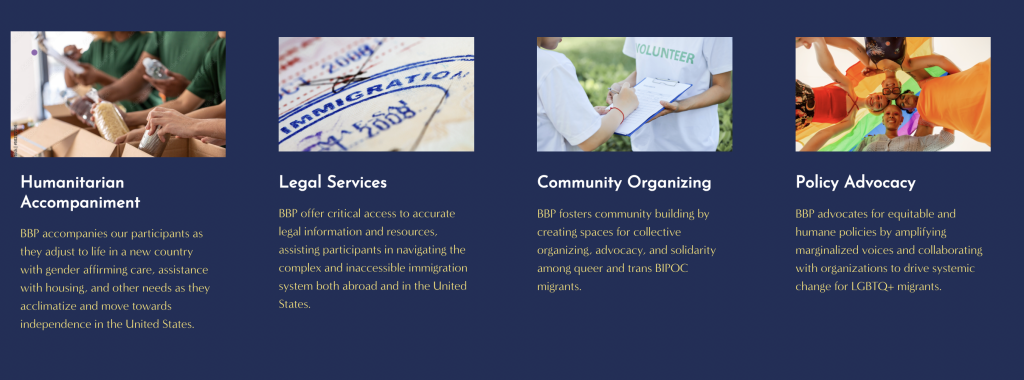

Kennedy Richardson, an outreach coordinator at the Border Butterflies Project at the Transgender Law Center, said policy decisions have immediate consequences.

“Every ICE memo, every anti-trans bill, becomes a barrier someone has to live through,” he said. “For immigrants, a mismatch between your ID and your gender isn’t just inconvenient. It makes you a target.”

Richardson added that while recent court injunctions have blocked parts of the Trump administration’s executive orders, those victories are temporary.

“Real safety doesn’t come from injunctions,” he said. “It comes from structural change. We need policy that sees us and protects us.”

As legal protections remain in limbo and political hostility intensifies, transgender immigrants like Mayorga, Wang, Zhong and Li remain suspended in uncertainty. They are caught between countries, documents and identities. For many, visibility is both a necessity and a risk. Survival depends not only on legal status but on community, care and the ability to keep being seen.

Both Wang and Zhong describe feeling trapped between two unwelcoming worlds.

For Wang, returning to China as an openly transgender person carries serious risk.

“There was once a thriving queer scene in Beijing,” they said. “But now it’s almost impossible to live openly.”

In May 2023, the Beijing LGBT Center, a cornerstone of the city’s queer community, was forced to shut down. It cited “uncontrollable forces” amid increasing government pressure.

In the United States, that same visibility comes at a different cost: politicization, violence and exclusion.

“My immigration status can’t be changed overnight,” Wang said. “But through my art, I can assert our existence and humanity.”

The stories of Wang, Zhong, Mayorga, Li, Pritzkat and Salcedo reflect a shared question. It runs beneath policies and paperwork, beneath job titles and support groups.

“Where do we go from here?“

There is no single answer. But the people who live that question each day are already building one through survival, community and resistance.