The Dealer

In 1957, a young Italian boy visiting an archeological dig in Tripoli, Italy pocketed a few fragments of a 4th-century AD vase that had captivated him. As he was leaving, a security guard caught him and ordered the pieces to be returned — until an archeologist on site intervened, telling the guard to let the boy keep his new treasured pieces of antiquity. The boy later had the vase restored and carried it with him through his years at Princeton and into his career as an art dealer in Rome, until well into his 40s, when an Italian magistrate seized it due to its lack of authentic provenance records to verify the Italian origin.

That boy was Edoardo Almagià, who would grow up to become one of the most infamous art dealers of the century, all while publishing blogs that detail his biography and business on his website, including the vase from his boyhood. By the time that vase was confiscated, Almagià had been illegally trafficking antiquities for two decades and had evaded U.S. and Italian law enforcement four times — in 1992, 1996, 2001 and 2006.

He had been organizing tomb raiders, or tombaroli, to raid archeological digs and smuggle antiquities into the U.S. where he would use his Princeton network to market Italian antiquities with fraudulent provenances into the most esteemed museums, galleries and private collections of the western hemisphere.

The vase from Tripoli was the first of 221 antiquities, valued at almost $6 million, that authorities would eventually confiscate from him. Even so, those are but a dent in the 2,000 total stolen antiquities, valued at tens of millions of dollars, that the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) has attributed to the dealer since starting to track him in 1992.

He evaded arrest for the past three decades until this past October, when the DA delivered an 80-page warrant. Almagià, now 78, faces charges of conspiracy, scheme to defraud and criminal possession of stolen property from the Manhattan DA in the broader scheme of art trafficking. With Almagià now residing in Italy, the DA relies on a “red notice” filed with Interpol for an arrest to take place under Italian jurisdiction.

Almagià himself, who agreed to speak briefly over the phone but would not discuss certain topics without the promise of an in-person interview, maintains that the charges are “completely ridiculous.” He says he has read the warrant himself, and on account of the DA’s narrative, says, “We are really dealing with science fiction here.”

The stories of antiquities deals detailed in the arrest warrant do indeed read like an action movie, complete with villains and thieves and heroes, some featuring Almagià himself, others featuring side characters with spin-offs of their own.

According to the warrant, in 1986, former vice director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art allegedly smuggled a Greek pot known as a lekythos out of Greece in a diaper bag, as he bragged while discussing the donation of his 166-piece collection, including the pot, to the Tampa Museum.

In 2006, an Italian prosecutor brought trafficking charges against Almagià and his network. Almagià’s “primary supplier” cooperated with law enforcement, admitting to raiding “tombs and archaeological sites in Cerveteri… and [selling] his finds to Almagià.” The supplier was Mauro Morani, who one convicted antiquities dealer described as “a greedy man, a playboy who loves expensive suits and cars, and, therefore, is always ready to partner with traffickers who agree to pay in advance and ensure good profit-sharing.”

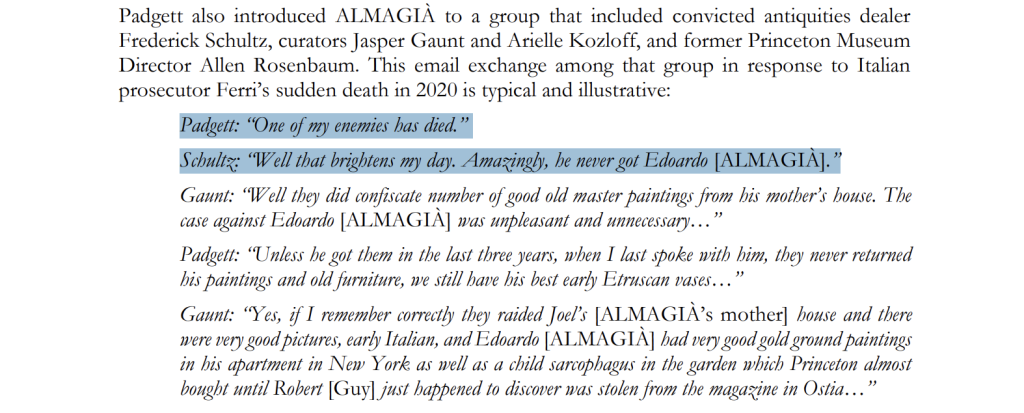

The Italian prosecutor of that 2006 trial, Paolo Giorgio Ferri, suddenly died in 2020 while working with the ATU on investigating Almagià. According to the emails seized for the warrant, when one of Almagia’s dealers found out about Ferri’s death, he texted convicted antiquities dealer Frederick Schultz, “One of my enemies has died.” To which Schultz responded, “Well that brightens my day. Amazingly, he never got Edoardo [Almagià].”

The warrant is littered with these vignettes of criminal activity that the DA obtained through access to his and his network’s emails. They feature Almagià speaking candidly about coordinating how to loot a dig site or the timelines of faking provenances. The warrant reads, “Almagià was this candid about his ongoing and criminal trafficking network. Indeed, he appears to have been quite proud of his mini-empire.”

Even so, this “mini-empire” revolves around antiquities that often sit at the lowest fine art price points, even while the sale of many of them accumulates to a successful career for dealers.

The federal government rarely pursues antiquities investigations. Robert Wittman, former founder and senior investigator of the FBI’s Art Crime Team (ACT), remarks that he never worked on an antiquities deal in his 20 years at the FBI, partially because “in the past, it was pretty much turning a blind eye to these types of things,” he said of the undercurrent of the crime within this industry.

The art world actors and their status only dramatize the crimes within it.

Matthew Bogdanos, chief and founder of the ATU, tells me how seriously his team sees their job of chasing down these good old boys clubs, according to him.

Almagià, however, says Bogdanos is “a part of the game, but he doesn’t know it.”

Michael Padgett, allegedly Almagià’s “complicit assistant” who has been dismissed of all charges since 2010, alike, warns me of the “morality play” I am involving myself in as a journalist. He and Almagià maintain that Bogdanos pursues them on his “witch hunts” only to “keep up the parade of seizures and triumphant news conferences if he mines the veins of past sin,” says Padgett. Still, while these larger-than-life characters, from tomb raiders to self-righteous dealers to vengeful cops, the criminal activity in the opaque antiquities world rages on, protecting the ultra-rich buyers and sellers from facing prosecution or jail time for decades of crimes.

Gentlemen’s Agreements

Almagià isn’t the only one of his kind. He belongs to a legacy of dealers that approve of and promote this kind of dealing. They say it’s how things have always been done.

Padgett, also a Princeton-educated art curator who worked at his alma mater’s own museum as the lead curator for ancient art, is still named frequently across the most recent arrest warrant.

It claims Padgett “attribute[d] stolen antiquities to ancient painters, thereby creating impressive pedigrees for unprovenanced antiquities” and helped to connect Almagià to prominent collectors and institutions who would acquire these antiquities for prices influenced by those fabricated records.

He, however, claims “almost all of the privately owned antiquities were not excavated by archaeologists.” Before the DA focused on this area of crime and many institutions changed their policies, Padgett said Princeton museum managers instructed him to find ways for objects with shady export records to make it into the galleries. In an interview, he told me he would encourage sellers to say they had no idea where the objects came from, rather than mention they could be from Italy but they did not have an export permit. That way, he could evade certain standards of verification, especially if the owner was willing to gift the object, not sell it.“That was my job,” he said. That was the “age of innocence,” he said, “when nobody thought it mattered.”

Padgett explained to me the difference between what dealers consider “stolen” versus “stolen stolen.” To Padgett, a work would be “stolen stolen” if it were taken from a person or a museum, but a work is only just “stolen” if it is dug from the ground or taken from a dig site.

To him, and to many dealers of antiquities, objects taken from digs are the standard. Padgett tells me the rules feel so alien to his work that he still is not sure “what would constitute collecting responsibly.” But more than anything, Padgett maintains that his dealings hurt no one. “There’s a lot of pain in the world, a lot of suffering, injustice, heartache, and none of it is caused by collecting undocumented antiquities. Get a life.”

The Cost

However, U.S. law enforcement monitoring and investigating these deals say the cultural norms don’t get a say in what is legal or not, and the consequences of these excuses are pervasive, even in sectors one wouldn’t expect.

Bogdanos is the central officer pursuing these crimes in the United States. As his unit’s niche is often an underfunded area of law enforcement, Bogdanos is essentially carrying the weight of prosecuting these crimes himself.

I asked him what he says to those who say antiquities trafficking is a victimless crime. He said,

“I guess they don’t really understand the value of art and antiquities and what it means to people around the world, especially in areas like Southwest Asia, where these are actually idols, objects of worship, which these people have worshiped for 1,000 years and were taken from them… It’s like saying to me, how do I respond to someone who says the Earth is flat? I don’t know where to begin.”

However, it’s not just cultural value sacrificed in these crimes. Bogdanos has been tracking the art trafficking out of the Middle East for years, and those art deals, among the powerful members of unstable regions where war goes hand in hand with the looting of cultural goods, often actually fund terrorism. “Not all antiquities trafficking funds terrorism. But some does, and enough does that it makes a difference. And when you consider exactly how much an IED or a bullet costs, $1 is too much,” he said.

Bogdanos says the important distinction his unit has made in the past years has been the concept of mens rea— whether someone knew they were buying stolen art or not. But today, many infamous dealers’ names are so popular in the industry that many who have acquired works should have known better.

“If you buy something from Giacomo Medici today, we are 100% certain you knew it was stolen. The whole entire world knows Giacomo Medici is a crook, Subhash Kapoor is a crook, Gianfranco Becchina is a crook, and Edoardo Almagià is a crook. Everyone knows that. So if you buy one today, that’s on you. You’re getting arrested flat out. But if you bought them from Medici in the 70s, nobody knew that Medici was a criminal in the 70s, so we never superimpose today’s knowledge on the individual’s knowledge. That’s the law, and we follow the law.”

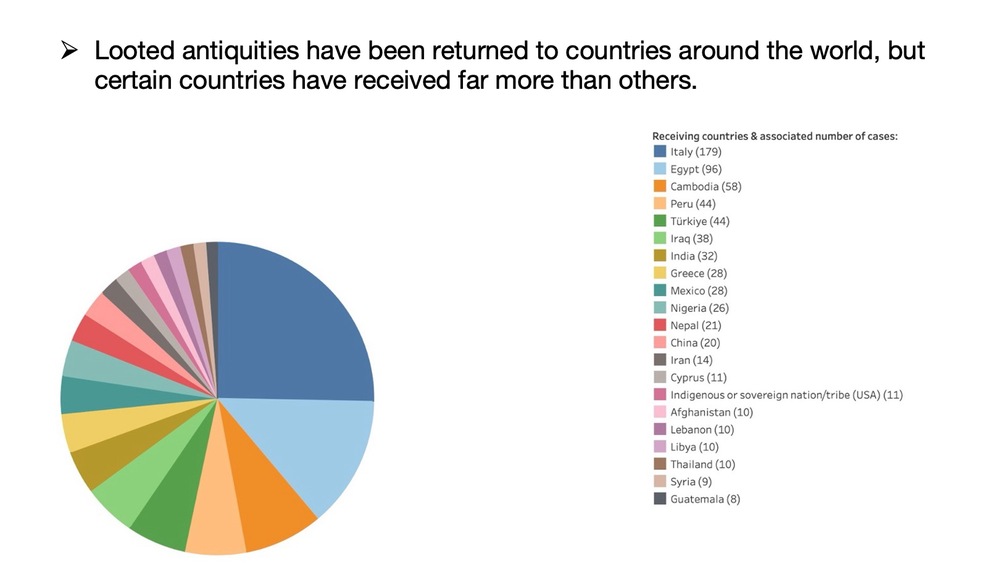

And the scope of these crimes is never-ending, considering how much of the ancient world is still buried in Italy, and how much simply lives in backyards in Italy or South America. Wittman says, “90% of everything that was in the ground in Peru is gone, and think of all the Italian antiquities that left the ground and ended up in collectors’ hands.”

Bogdanos says he is motivated by his love for the ancient world and his desire to protect the record of it. A Classics man himself, earning his Master’s while getting his law degree from Columbia University, his personal motivations are clear. He even quoted a Latin poet in our interview, “Who will guard the guardians, right?” His answer?

“We will, with a code of conduct.”

The Law

And these officers have a point, the laws on art crime have become incredibly sophisticated in the last 50 years. However, they are also getting increasingly more complicated.

During the 1970 UNESCO Convention, a new international standard of art trading was established. The convention produced the suggested legal framework for the definitions of international cultural trade and ownership. Most notably, it set 1970 as the landmark year for the art market to require verified provenance of every object outside of its country of origin. This meant dealers had more paperwork, and even more cause for concern. The legal record of how they sourced and acquired works for trade was flipped on its head, a process that had previously been riddled with shady deals and, often, theft. However, UNESCO offered a suggested framework, not international law. Each country still decides its own laws of ownership and exporting.

For example, the U.S. has very different patrimony laws given that most of the art traded here wasn’t dug out of the ground like it would be in a country like Italy, which has ironclad patrimony laws. The Italian government ruled in 1939 that everything underground in Italian soil belongs to the Italian government, no matter who owns the above-ground land.

E. Randol Schoenberg, a lawyer who argued a landmark art patrimony case at the U.S. Supreme Court, says this discrepancy between countries is one of the reasons why dealers and law enforcement experience such a disconnect in the art world. “That’s hard for Americans, especially people not versed in the law, to grasp,” he said. “It is counterintuitive for Americans, because we don’t have those laws on public ownership of stuff underground. So, a lot of these cases involve that complication.”

There’s also the legal matter of a “good faith purchaser” that changes across borders. In the U.S., law enforcement operates on “once stolen, always stolen,” according to Bogdanos. Meaning, if a piece of art is stolen and then sold, the new owner never “acquires title” to that work of art — they never truly own the art because it was stolen, even if they were not originally aware. But abroad in countries like France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland, some of the most thriving art markets in the world, anyone who buys art without knowing it is stolen can legally still own the art even once law enforcement discovers it was stolen in the past. Bogdanos says that’s a huge flaw in those legal systems. “That’s not a society I want to live in. I don’t like rewarding criminals,” says Bogdanos.

Almagià says “most of the things I sold, I bought them in Switzerland and England.”

Each dot on this interactive map is an illegal Almagià deal across 40 years.

While the laws vary by country, and enforcement remains difficult while institutions deny awareness of any theft, Bogdanos says it’s not stopping him from pursuing prosecution where he can. When I asked him if he wished there was more clarity in the legislation or legal precedent, he said, “There’s no need to change the law. It’s a poor carpenter who blames his tools. [The ATU has] got 17 convictions, more than 6,000 seizures from one unit alone. We’re doing fine. I have more active investigations than I can handle.”

The Dealers Left Behind

But dealers offer a different perspective. They argue the rules changed like a rug pulled out from under them. They don’t feel like criminals; they feel like heroes, and they particularly hate how Bogdanos speaks of them.

Padgett says, “We can’t just wheel out our mores and manners of today and expect everyone in history to acknowledge them.”

The arrest warrant for Almagià, written by Bogdanos, even features an email chain between Padgett and another convicted dealer writing that his “dream is for Bogdanus [sic] to come seize a [fake antiquity], trumpet his success on TV, and then be outed as a fool and a publicity hound.”

But beyond the feuds between the dealers and Bogdanos, these dealers say they don’t feel they are stealing the objects of history, but rather, saving them.

Almagià says antiquities cannot be trusted in the hands of law enforcement who he claims do not have the academic background to know what they are confiscating. “Look at the conditions of antiquities in Italy: monuments falling apart, places filled up with garbage, collapsing buildings…” Almagiá claims that antiquities seized by the government “end up in boxes in basements of museums called the ‘concentration camps of archeology.’” To him, it is natural that “the others get stolen.”

Schoenberg remembers the museum which he fought against during his trial believed it was their “duty to keep stolen property by any means necessary.”

Custodians or Criminals?

Law enforcement says this justification is a symptom of a larger issue, one of “willful blindness,” according to Schoenberg, in an industry that survives off some of the wealthiest powerful people across the world who are continuing to collect.

Shoenberg says, “There is a general feeling on behalf of people, whether they’re government or private institutions, that the default should be not to give things back. They feel that they’re the custodians and have a duty to the public and to the trustees of their organization to maintain things. And so if there’s any reason to keep something, they want to keep it.”

In fact, in his case which involved a painting stolen by the Nazis during WWII, he argues that the Austrian museum fighting to keep the painting “compounded the injury of the initial wrongdoing by doubling down and saying ‘we’re gonna defend this.’” In his case, both the original family estate that once owned the painting and the museum that bought it without knowing it was stolen argued that they had the right to it.

Today, the problem lies less in the lack of enforced standards and more in the jurisdiction of those standards. Bogdanos, after years in this field, says, “The good news is there has been a sea change” among the U.S. institutions. Wittman agrees, saying the bad press from Bogdanos’ many probes is encouraging better behavior. “No museum or auction house wants to be involved in illicit antiquities trading because it’s not profitable,” he says, remarking that the cost of fighting for an antiquity rarely outweighs what institutions paid for it.

However, the mismatch of expectations and definitions is still reflective of a status issue within the art industry. The dealers within it, surrounded by cultural objects of beauty and mystique, consider themselves a part of a privileged class that shouldn’t have to confront the technicalities of trade, or if they do, they don’t consider any rules they have broken to be worthy of prosecution. What dealers see as a cultural norm of their practice, law enforcement sees as the criminal negligence of ownership, export, and trading of an asset class.

But Bogdanos says that’s all in service of a centuries-old boys’ club that promotes “off the books, private, gentlemen’s agreements” in service of “the way it was done forever.” Bogdanos, called a “pit bull” in his Atlantic profile, a retired Marine colonel and amateur middleweight boxer, tells me there’s no logical mercy for these excuses. “Rich people who have all this income to buy antiquities may not like the law applying to them with equal force. But the law against stolen iPhones is the same law against stolen antiquities. Once stolen, always stolen, no matter how many times it changes hands, no matter how many borders it crosses,” he says.

And law enforcement says, even while they pursue dozens of cases at a time, this crime is rampant and difficult to retroactively prosecute. “A lot of people that did it got away with it absolutely a whole lot more,” says Wittman. “We don’t catch the smart ones.” And Almagià says “dealing is the tip of the iceberg.”

The “smart ones” are those who leave the U.S. As mentioned, the patrimony laws in Europe allow for a “good faith purchaser” to acquire title legally. Meaning that any collector, gallery, museum or auction house that buys a work of art but did not know that it was stolen, or at least can prove in court that it didn’t know, can trade stolen antiquities freely. Bogdanos sees this as simply exporting crime abroad. “It’s one of those secrets that nobody wants to talk about,” he says. “Good stuff comes here and the price goes up, and the bad stuff goes to Europe.” There, those “names that everybody knows are radioactive” and indicative of a false provenance don’t cause dealers any trouble.

“Why did Sotheby’s, four years ago, move their entire [antiquities] operation to London and Paris? Why did the European Fine Arts Fair, again, one of the largest in the world, reduce their New York antiquities sales and now focus primarily on Maastricht and London?” he asks me. “You know why, and so does everybody.”

All historical images from almagia.it. All artwork photography from 2023 warrant.