Gen Z is falling into sports gambling addiction. Some companies may be betting on it

The sports gambling epidemic has hit the younger generation with its in-your-face marketing, and the damages are only continuing to increase.

“I’m not gonna lie, it gets me really excited to be 21.”

That’s not in reference to alcohol. Not about drugs or tobacco. That’s what Ethan Makle, an 18-year-old senior at Bethesda Chevy-Chase High School in Maryland, said about being able to gamble legally on sports betting apps such as FanDuel or DraftKings.

Makle is just one of many in Generation Z — born from 1997 to 2012 and raised in the internet age — who have taken up the new hobby since it became legal federally in 2018. There have been few to no regulations on the practice in its new, digital form as legalizations state by state shape the new market.

Apps like PrizePicks and Underdog allow those 18 and over to risk money on what they classify as “daily fantasy sports.” On an app like PrizePicks for example, you are not betting on a team’s performance, rather, you’re just gambling on the performance of a singular player. This does not meat the legal definition for a “sportsbooks,” which allows these other companies to operate with different rules.

Currently, 32 states along with Washington, D.C. offer mobile sports gambling through regulated United States sportsbooks. But in every single state, you can wager money on sports in some fashion — whether through mobile sportsbooks, daily fantasy betting or tribal gaming opperations — except for Idaho and Hawaii.

Another popular app that moves around the loopholes that is growing in popularity — with 120,000 5-star reviews on the Apple app store — is Fliff. Unlike the other apps when making an account on Fliff, you aren’t prompted to verify your age until you try to withdraw your earnings. You can bet and “deposit” money — Fliff revolves around virtual currency, instead of “real” money — freely while underage.

If you win enough Fliff coins, you can then redeem them for gift cards from Amazon and other companies.

Local governments and advocacy groups have called into question the marketing tactics employed by some of these companies that lured millions of new users in the past few years. And there are some who are trying to rein it all in.

On April 3, the city of Baltimore sued both DraftKings and the parent company of FanDuel, Flutter Entertainment, accusing them of “engaging in deceptive and unfair practices to target and exploit vulnerable gamblers.”

“These companies are engaging in shady practices, and the people of our city are literally paying the price,” Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott said in a statement to ESPN regarding the lawsuit. “DraftKings and FanDuel have specifically targeted our most vulnerable residents — including those struggling with gambling disorders — and have caused significant harm as a result.”

FanDuel declined ESPN’s request to comment in response to the lawsuit.

While the city of Baltimore takes action against these sports books, almost nobody else is, and the public is left without much of a defense against what some call predatory practices.

The Big Boom

The domino effect began with the 2018 Supreme Court case Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association, which struck down a federal ban on states authorizing sports gambling.

For a long time, the sports world confronted issues with gambling and leagues opposed it. From the 1919 Black Sox rigging the World Series, to Pete Rose being banned from the Hall of Fame for gambling on his own teams, to NBA referee Tim Donaghy rigging games, there were always problems.

“[Look at] basically all of cinema: Sport would be portrayed as something innocent, like the Garden of Eden, and then gambling would come in, and it would be [depicted] like the serpent,” said Daniel Durbin, the director of the USC Annenberg Institute of Sports Media and Society. “In [Gen-Z’s] lifetime, it’s gone from being an absolute anathema that should not be allowed anywhere near sport to more or less a widely accepted part of sports activity.”

Since the 2018 Supreme Court case, the number of these apps has grown — and so has the user base. The total amount of money wagered on sports in 2017 was $4.9 billion, according to a JAMA Internal Medicine study.In 2024, that number ballooned to $148.8 billion.

“There’s always somebody dumb enough to bet something, and you have a new territory where you don’t have the level of regulation, where you don’t have the regulation of community and where you don’t have the level of a feeling of corporate responsibility for other people,” Durbin said. “So you have this place now where your sense of responsibility to others is pretty much nil, and gambling, which is a huge money-making proposition. … If you open the door to it, of course, it’s going to flood in.”

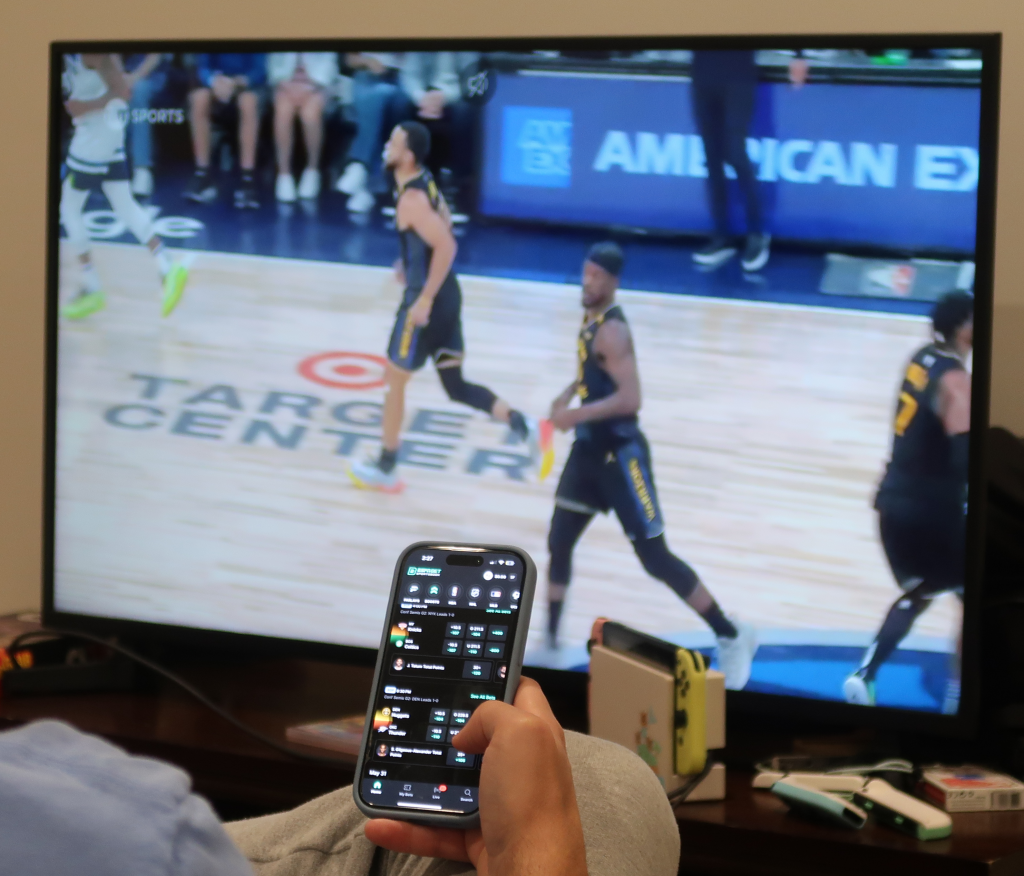

It’s taken a hold on the sports community. When people watch sports on TV, they’re flooded with advertisements about gambling, and many people jump right in — especially young people.

Syd Fryer, a 21-year-old junior at NC State studying political science and Spanish, saw how all of her friends started sports gambling as soon as they hit 21. When she finally did, she decided to as well.

“I was excited to start doing it, just because I’ve, seen all my friends doing it … I used all eight of my bonus bets [on the apps] within a couple of days, because it just was fun,” Fryer said.

A 2023 survey of just over 3,500 18-22 year olds by the NCAA found that 58% “have participated in at least one sports betting activity,” while 67% of those living on their university’s campus bet on sports and tend to bet at a “higher frequency.”

“I’m always asking all my friends, and they ask me ‘Yo, what bet did you place today?’” said Cian Schott, a senior studying Neuroscience at the University of Colorado. “If a game is on, I feel like I have to throw some money on it, because then I’ve got something to root for.”

Dan Field is a clinical director of West Side Gambling Treatment who specializes in gambling addiction therapy. Field added how dangerous sports gambling is, especially for those who are so young and still learning.

“It’s kind of like if someone had a really, really great experience with alcohol or cocaine as an adolescent — like a really heightened experience. That big spike in dopamine and remembering that experience can then make them want to drink or use coke in the future,” Field said. “Similarly, if people are part of a big gambling win, whether it’s a three-game parlay or a crypto coin that they chose, that can create a lasting imprint on the brain that makes someone want to return to that feeling or that potential to earn a lot of money.”

David Carter, an adjunct professor of sports business at USC, noted that that’s what the companies want. They want for that feeling to be replicated and to create life-long customers.

“I enjoy it and it’s a fun thing to do with my friends, but I don’t do it just for the money. I just do it for the feeling I get from it,” said Oskar O’Geen, a 18-year-old freshman studying agricultural and environmental technology at the University of California, Davis.

The House Always Wins

Many see sports gambling as a fun pastime and a different way to engage with sports. But at its core, it’s still a vast moneymaker for those offering the bets.

The American Gaming Association reported that $13.71 billion in U.S. sports betting revenue was generated in 2024. This was an increase of 25.4% from 2023, and the numbers are projected to continue to climb according to the AGA.

The Wynn sports book in Las Vegas is home to thousands of bets every single day. Photo: Stefano Fendrich

“[These apps] are looking back and saying, ‘How do we push the limit based on what the government allows us to do, based on what our consumers feel is inappropriate?’” Carter said. “There’s no reason to think they’re not going to continue to uncover ways to entice the gambling audience with greater greater opportunities, slicing up the bets, even more so the profits.”

Certain apps, such as PrizePicks and Underdog, only take parlay wagers, the least profitable form of sports betting for a gambler. As Washington Post contributor Danny Funt points out, on a typical bet, if one team is going to win the game, a sports book will make $5 for every $100 wagered. For parlays, customers tend to lose $30 for every $100 wagered.

But the enticement to win big is too much for some people to resist.

“I talk to people my age and people [in Gen-Z], and they only bet parlays, especially like 10-leg parlays that are basically just buying a lottery ticket,” Millennial Funt said. “The odds that you’re gonna pick 10 things, and they’re all gonna be successful, is astronomical. … Parlays are just lighting your money on fire.”

Funt is currently writing a book about sports betting legalization. He’s been following some of these companies for years and has seen some of the new tactics these apps use to make it even easier to gamble.

“If you’re not a ‘traditional’ sports bettor, you’re like, ‘I don’t want to go up to a counter and say a bet and get it wrong and then, this guy who’s taking bets, gets mad at me.’ So that has been a barrier to entry for people, and they’re trying to do away with that,” Funt said. “On PrizePicks or Underdog, often instead of saying ‘This combination is +300’ — like traditional gambling verbiage — they’ll say, ‘3x your money,’ so that it’s as universal as possible.”

Funt even noted a unique marketing tactic Underdog would use to entice people to bet. He saw that the app introduced a dating app-like interface to place your bets. The user would just need to swipe right to add a pick to their parlay or swipe left to see the next selection.

“You can imagine how it just makes it as frictionless as possible and it disguises how bad the odds are,” Funt said.

The decision behind implementing the “Superstar Swipe” interface is to promote a switch of fandoms from teams more toward players, according to Underdog’s senior director of sports betting and business development, Matt Garrigan.

“At the core of the Underdog Sportsbook thesis is giving customers a unique and friendly way to engage with our products, and constantly iterate and innovate to build formats they will love to play,” Garrigan said in an August 2024 interview with EGaming Review. “Superstar Swipe is an example of that commitment to our customers.”

Sports gambling apps want to make it as easy as possible for their customers to bet, removing the barrier to entry as much as possible Carter added.

Many college students are falling into the trap. A poll done by Intelligent.com of 986 college students in December 2022 found that one in six college students who gamble on sports reported using financial aid or student loan money to place their bets. It also found that just under a third of those surveyed said they will run up their credit card or even spend less on necessities such as food to fund their gambling.

“The influx of promotional materials and marketing and advertising has made it seem [like] something that’s fun and recreational,” Field said. “All of these [marketing] elements are combining to create a space where people feel more normal when they’re betting and more supported by friends and because there’s a false sense that this could be a skill-based pursuit, that it might be a viable way of making money.”

You Get a Free Bet, You Get a Free Bet

The reason Schott first got into gambling was the allure of the “free bets” all of these sports gambling apps have to offer.

“I knew a lot of people that were doing it, and when I turned 21, everyone sent me their referral code to join,” Schott said. “There’s a whole bunch of different apps that’ll give you basically free money to just sign up.”

What Schott is referring to are the “risk-free,” or bonus bets that sports gambling companies use to entice new signups and entice people to start betting. Typically, for most apps, you send a referral code to a friend and, after they place their first bet or make their first deposit, you get a certain amount of “free bets” to place. These introductory promotional bonuses can range anywhere from $50 all the way up to $1,000.

DraftKings offers many promotions just to join the app in order to entice new bettors. Photo: Stefano Fendrich

“‘Risk-free’ means there is no risk. [But] there is risk. Undeniably, there is risk,” Funt said. “The thing is they don’t function the same as money, so that’s misleading. You don’t get the bonus money, you only get the payout. So in that case, if I bet 100 bonus dollars … on a -10,000 bet …, I make 5 cents off that. So that’s deceptive. I would say calling anything ‘free’ that you have to pay for, or risk losing money to get, is not free.”

USC professor Carter sees the “free money” as a different marketing tactic altogether.

“[The companies] are saying, ‘Hey, the lifetime value of one of these gamblers, particularly at a younger age, is tremendous, and so we can run these promotions and make them feel as though we’re giving away a lot of money and opportunity, when in fact, we know we’re going to get that back over time if we continue to market to them,’” Carter said. “It’s a way to get these young people in, knowing that if they’re of that age and they maintain a gambling presence for their adulthood, that’s going to be worth a tremendous amount of money to the gambling operations.”

Although many Gen-Z gamblers don’t have the “bankroll” to be placing many big-money bets, the addiction can start very early, regardless of how much is being lost on a single bet.

“Your brain isn’t fully developed until you’re like 25, so as a result, you’re particularly inclined to impulsive behavior or risk seeking, both of which are just classic traits of gamblers,” Funt said. “[As someone in Gen-Z], you’re basically predisposed to overdo it [with] betting, which is alarming.”

The marketing of sports gambling has been a point of concern for many, including those in the government. Right as March Madness — the NCAA’s end-of-season basketball tournaments — was about to start this year, U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat, and U.S. Rep. Paul D. Tonko, a New York Democrat, reintroduced the Supporting Affordability and Fairness with Every Bet bill.

The SAFE Bet Act seeks to create protections for consumers when gambling on sports, as well as standards for the mobile sports gambling industry. The bill would require states where sports gambling is legal to comply with a new set of federal regulations in three main categories: marketing, affordability and artificial intelligence.

“We have seen far too many — especially young people — driven into gambling abuse disorder, which is a disease. Like all addictions, we must take every step to prevent and treat it — not amplify or exploit it,” Blumenthal said in a press release when the act was reintroduced. “Sports betting has become a science for gambling entities. It is the science of exploitation and targeting and tracking individuals who are prone to addiction. The science of targeting and tracking gamblers who lose bets and enticing them to bet more and more until they are driven into ruin.”

Notable regulations include disallowing sportsbook marketing during live sports broadcasts, getting rid of “programming designed to induce gambling with ‘bonus’ ‘no sweat,’ ‘bonus bets’ or odds boosts,” prohibiting apps from allowing more than five deposits in a 24-hour cycle, and to ban the use of artificial intelligence to monitor a customer’s gambling habits and offer “individualized promotions,” based on the AI among other things.

However, the efforts of Tonko and Blumenthal — as well as by the city of Baltimore— have been isolated. Since the Supreme Court decision legalizing it, sports gambling has largely gone unchecked in the eyes of the law. The city of Baltimore’s case is the first by an American public entity against online sportsbooks since the 2018 case that opened the floodgates.

“[Other than] these sort of sporadic efforts to regulate or lessen the aggressive marketing to kids, it really seems like the Wild West right now,” Field said.

Trust Me it’s a Lock

Sports gambling has turned into a communal thing, with many asking their friends for advice on what to bet on. Photo: Stefano Fendrich

Sports gambling has taken on a vastly different form since it became legalized. It has turned into a thing that pops up at every sporting event on TV, and that is all over sports media. It’s been glamorized in the way it’s promoted and talked about, but Gen-Z has seen the dark sides.

Darrian Merritt, an 18-year-old freshman journalism major at USC, has been gambling since his junior year of high school. He was able to move around the bans and place bets with his friends every time he would watch sports. Merritt recalled a “dark time” when he found himself “chasing” his bets — increasing his wagers and repeatedly betting after losing multiple times.

“I chased really hard on this one game because I just wasn’t that good at betting yet, and I decided to keep live-betting on the game.” Merritt recalled. “The thing with live betting is, it keeps flashing in your face, and then it’s gone. So it’s a heightened sense of urgency to it, since it’s only there for a short time. … I think I ended up making maybe five or six live bets on the game [after my initial bet lost].”

Live betting has become another big boom for sports books according to Funt. Especially for Gen-Z, where attention spans are only shrinking.

“Kids aren’t waiting for the result of a game. They don’t have the patience for that.” Funt said. “They’re, you know, betting on a specific play to happen … It’s like the crack cocaine of sports betting.”

And sports gambling is another addiction that is not easy to shed. In New Jersey — the first state to legalize sports gambling after the Supreme Court ruling — half of the people who bet on sports do it every day, but 70% of them say they wanted to stop altogether.

Field has been working closely with “problem gamblers” for over a decade and has seen the many sides to the addiction. He finds they tend to have a lot in common.

“What’s unique about gambling is the ‘chasing cycle,’ which is almost universal. You have a big win, and you have the feeling that that’s going to happen again, or that you’re ‘special’ and that it’s inevitable that, because of your ‘specialness’ or your ‘talent’ in knowing about sports, that what happened is going to repeat,” Field said. “Most people don’t understand that sports betting is really much closer to slots — it is pretty random, and that you may feel that you have an edge, but you don’t, in fact, have an edge.”

Field said that over the last few years, he’s seen an increase in younger patients, some as young as 15 or 16. He explained that the sports gambling apps are designed to make it easier to gamble and, thus, lose more money.

Field has seen first-hand in some of his patients the harm that sports gambling can cause.

“[On some apps,] it’ll take 72 hours to be able to withdraw your money, and if you’re a problem gambler, [it’s an issue],” Field said. “You’re up $7,000, which is what happened to this 16-year-old that I’m counseling, and he couldn’t get the … money out. He was like, ‘You know what? Screw it. I’m just going to try to turn my 7 into 10,’ and he lost it all. That’s where it became revealed to his parents that he, in fact, stole $4,500 from them, which is why they contacted me.”

Added Field: “It’s more than ‘The house always wins.’ The house knows you and what your behavior is and how to pull you back into action.”

Which is how Makle, the high school senior in Maryland, got drawn in at age 16 during the 2022 World Cup, by using Fliff, which permits underage people to gamble without using real money.

Three years later, Makle is betting with real money.

“Where things start to go south for me is when I start betting with my emotions, right? I’ll win a couple, and I’ll get happy,” Makle said. “Then I’ll make a big bet and I’ll lose it all, or I’ll lose a bunch in a row, and then I’ll get really mad, and I’ll make a big bet.”