When Telling the Story Could Put Them at Risk

Before you move on to read about a family with El Salvadoran roots, it is important to understand the difficult decision that shaped how it was told.

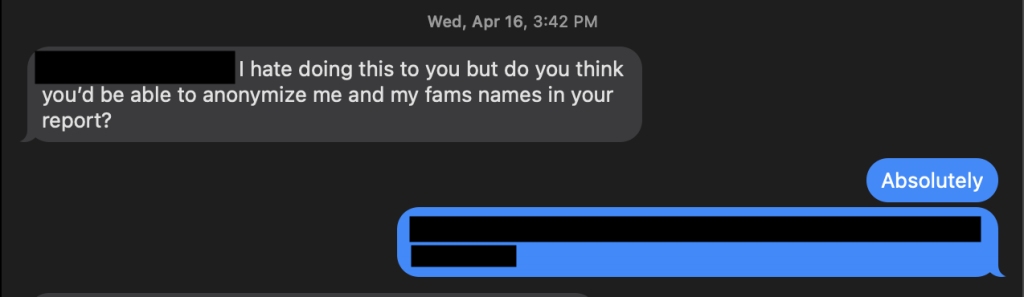

The family at the center of this story asked for anonymity due to mounting concerns regarding their immigration status. That choice was not made lightly, and it reflects the deep sense of vulnerability they feel simply by sharing their experiences. Throughout the reporting process, their openness was marked by understandable caution. They know that speaking publicly about their lives, their status, and their fears can carry consequences that extend far beyond words on a page.

In the end, they decided their story needed to be told, but not in a way that could expose them. Names in this piece have been changed. Personal details, including locations and professions, have also been adjusted to protect their privacy. These edits do not obscure the truth. They are necessary in order to share that truth safely.

Every word that follows is rooted in fact. Every quote is real. And every moment of uncertainty, resilience, and quiet hope belongs to them. Protecting their identity does not make their story any less urgent or authentic. It simply reflects the reality of telling stories in a world where even being honest can feel dangerous.

They Built a Life in America. The Law Still Calls Them Temporary.

They live as neighbors, workers, and friends, yet their right to remain has always been under scrutiny.

By James Garvey

Antonio never questioned where he belonged. His earliest memories are not from his birthplace of El Salvador, but of Los Angeles. He warmly recalls summer afternoons spent in his grandmother’s small apartment in Los Feliz, of running up and down the steep stairs, of family dinners where Spanish blended with the sounds of the Dodgers game on TV.

He grew up here, went to school here, got his first job here.

He watched friends plan summer trips abroad, heard classmates talk about study abroad programs, but for him, the thought of leaving the country was never an option.

“I always wanted to do that, to travel, to experience things, but I’m just very restricted. ‘Cause it’s like, you can probably leave, but you’re not coming back,” said the young man, who is being identified by the alias of Antonio given worries of his immigration status.

His parents, Carlos and Rosa, understand this uncertainty all too well. They left El Salvador in the late 1990s, seeking stability for their newborn son, only to find themselves caught in an immigration limbo that has lasted more than two decades. They arrived in Washington, D.C., before moving to California, where they relied on family to stay afloat.

“We lived in a closet at my mother’s house for almost two years,” Carlos said. The room itself was only about 6 by 10 feet.

Despite the hardships, they built a life. Now, decades later, they find themselves in a similar, if not more strenuous place — waiting, renewing, hoping.

“Every year we pay for new documents — like $1,500 every single 18 months,” Carlos said. “It’s terrifying.”

Every 18 months, he is reminded by a bureaucratic deadline that, to the government, he is still temporary. His life in the United States is a house built on shifting sand, dependent on an immigration status that could be revoked with the stroke of a president’s pen.

For decades, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) has served as a lifeline for immigrants from nations destabilized by war, disaster, or unrest. First created in 1990 as part of the Immigration Act, TPS offers temporary legal status and protection from deportation for nationals of countries experiencing war, environmental disaster, or other extraordinary conditions. As of 2025, countries like El Salvador, Syria, Haiti, Venezuela (recently revoked), and Afghanistan have had populations protected under the program. But TPS offers no path to permanent residency — recipients remain in limbo, subject to renewal every 18 months at the discretion of each administration.

For Antonio, it was a silent backdrop to his life — until he was old enough to realize just how precarious his situation was.

“I always knew there was no way of me becoming a citizen,” he said. “That was always distilled in me. I knew that every time the TPS expired, you would have to go every single time and do your biometrics.”

Now, with a new administration in power and immigration laws tightening, Antonio’s family faces an even greater sense of unease. In fact, as this story was nearing completion, after initially being identified, the family requested complete anonymity given the tenor of the political moment and their fears.

The Laken Riley Act, named for the murder of Georgia nursing student Laken Riley, overwhelmingly passed the House and Senate with all Republican and some Democratic votes earlier this year. President Trump made it the first piece of legislation he signed this term. The measure expanded immigration enforcement, granting federal authorities broader powers to detain and deport undocumented immigrants — including those who are merely accused of crimes, not necessarily convicted. Supporters of the bill framed it as a necessary response to public safety concerns after Riley’s death, which allegedly involved an undocumented immigrant with prior arrests. Critics, however, have raised alarm over the act’s potential to erode due process protections, arguing that deporting individuals based solely on accusations risks punishing people before they have had their day in court. The law also compels local law enforcement to cooperate more closely with federal immigration agencies, reigniting debates over sanctuary policies and the reach of federal power.

“It’s very scary,” Antonio said. “It passed, and there just wasn’t really much of a fight to stop it. It just gives such an ambiguous definition… even, I think, emphasis on ‘suspicion’ — you don’t have to have any sort of probable cause.”

As debates over immigration intensify, Antonio’s family represents a larger reality: immigrants who have built their lives in the U.S. but remain vulnerable to shifting political winds. Their story is one of resilience, fear, and the ongoing fight for a sense of permanence in a country that has been home for nearly their entire lives.

“It’s ironic calling it Temporary Protected Status,” said Antonio, given he has lived in the U.S. for more than two decades. “What the hell are we all doing?”

In 2001, Antonio’s family qualified for TPS after a devastating earthquake struck El Salvador. It provided them temporary relief, but not a path to permanence. The status is supposed to be renewed every 18 months, subject to the administration’s discretion. Every cycle brings new paperwork, new biometrics appointments, and thousands of dollars in legal and processing fees.

“It’s deceptively simple,” Antonio said. “If you know what you’re doing, it’s straightforward, but if you don’t… and for people where English is a second language, or they don’t even know any English — that just convolutes so many things.”

Rosa, Antonio’s mother, described it more bluntly: “For me, I never have… peace.”

That lack of peace extends beyond logistics. The threat of sudden policy shifts has become a feature of the family’s life. When the Trump administration announced its intention to end TPS for El Salvador in 2018, panic swept through the community. While the decision was later blocked by the courts, it cemented a message: nothing is guaranteed.

These threats became far more real with the passage of the Laken Riley Act and the administration’s revived use of the Alien Enemies Act. Together, the measures allow federal authorities to detain immigrants on suspicion alone and expedite deportations from countries labeled as national security concerns.

Janet Murguía, president and CEO of UnidosUS, the nation’s largest Latino civil rights organization, says these policies reflect a deeper erosion of democratic values.

“We are seeing extreme overreach, threatening a constitutional crisis here,” she said. “It leaves a huge loophole … around who can be subject to immediate deportation without due process.”

Lisa Navarrete, a senior advisor at UnidosUS, warned of the broader consequences: “Nobody can tell someone’s immigration status by looking at them … we’re seeing it already with people being picked up for things like speaking Spanish or the clothing they’re wearing or they have a tattoo.”

UnidosUS and its partner organizations offer legal clinics, policy advocacy, and community outreach to help families like Antonio’s understand their rights and navigate sudden shifts in immigration policy.

For Antonio, the fear is personal. With Venezuela’s TPS recently revoked, he worries El Salvador could be next. “You kind of feel like you’re on the chopping block,” he said.

And it’s not just about him. His family is part of a broader patchwork of communities whose futures hinge on the decisions of officials often far removed from the realities they face. Murguía put it plainly: “They can screw up, but it’s innocent people who pay the price.”

Despite the uncertainty, the family continues to build a life. Antonio’s sister, a U.S. citizen, has filed a petition to adjust their parents’ status, but the process is slow and uncertain. Antonio, meanwhile, is weighing marriage with his long-time girlfriend as one of the only viable legal paths to residency.

“It’s annoying and unfortunate, but thankfully … we were already planning on getting engaged, but now it’s just been fast-forwarded,” he said.

For Antonio, love and law are now uncomfortably intertwined. What should be a deeply personal decision has been accelerated by legal necessity. “We’ve talked about it more seriously in the past few months than we ever have,” he said. “It’s not how you picture starting a marriage, planning it around immigration paperwork.”

Still, he’s grateful for the option. Some of his peers don’t even have that. “I know people who don’t have a path at all,” he said. “It’s just survival for them. At least we have a few things we can try.”

For Murguía, stories like Antonio’s family’s are a source of both concern and inspiration. “Without a doubt, it’s our young people,” she said. “They are resilient and they’re incredible contributors … We should be embracing these communities.”

That embrace, however, feels elusive. From policy reversals to language that frames immigrants as threats, the environment has become increasingly hostile. Antonio feels it even when doing everyday things — shopping, driving, or applying for work. “A lot of jobs will automatically filter you out when you say that you need some sort of sponsorship,” he said.

Antonio’s path hasn’t been easy, but he’s made the most of every opportunity. He graduated from college and became a licensed CPA — an achievement that speaks not only to his drive, but also to the overlooked potential of immigrants with uncertain legal status.

Yet, he pushes forward. Recently moving to the Bay Area, he works full-time at a major consulting firm, contributing as anyone should, no matter their documentation. “You do what you can with what you have,” he said. “You don’t really have another choice.”

As the 2026 election cycle nears, UnidosUS has turned its focus toward civic engagement. “We’ve registered a million new Latino voters over the last 12 years,” Murguía said. “We want to make sure we can continue to leverage the voice and vote of the Latino community.”

But policy change is slow, and Antonio knows this.

For now, his days are filled with work, family, and waiting, always waiting. “You just have to hope for a better future,” he said. “But hope doesn’t change laws.”

And yet, he holds onto it.

Because hope is what carried his parents out of El Salvador. Hope is what kept them going through years in a tiny room, juggling jobs and raising kids. Hope is what kept Antonio pushing through when his classmates left for study abroad programs he couldn’t attend, pursuing strong academics, and contributing to his community.

Hope doesn’t change laws, no. But maybe stories like his can. Maybe if enough people listen — not just to the slogans and the headlines, but to the lived experiences of families like Antonio’s — change won’t seem so impossible.

“I’m here,” Antonio said. “I’ve always been here. And I’m not going anywhere.”