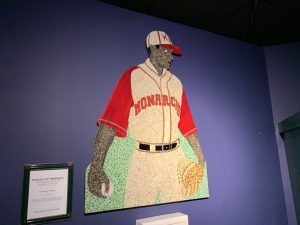

Kansas City, MO.—The sport of baseball has been around for well over a century and has produced countless stars and incredible moments. The New York Yankees, St. Louis Cardinals and Los Angeles Dodgers stand among the most historic teams in the sport, but alongside them existed such teams as the Kansas City Monarchs and Homestead Grays.

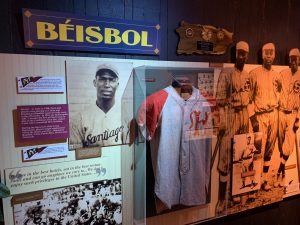

These teams operated alongside Major League Baseball and were part of a collective known as the Negro Leagues. At the time of the leagues founding in 1920, baseball had not yet been integrated, so rather than sit and wait, hundreds of black, Hispanic and even some women created their own teams and a league to compete in.

While these teams never appeared in Major League Baseball and some players never lived to see integration, their mark on the sport is undeniable. The teams that they were part of transcended the sport and were just as good and, in some cases, better than their white counterparts.

Still, while these teams transcended the sport and played a crucial role in American history, you will not find them in a traditional grade school history book. As a result, much of that history has been lost to time and at one point was on the verge of being forgotten forever.

View Negro Leagues historical map.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, MO. aims to change that by preserving the history of the league by informing baseball fans and non-baseball fans alike. In doing so, the museum channels the spirit of its players as it seeks to safeguard an important part of not only sports history, but American history.

Bob Kendrick, president of the museum, is tasked with safeguarding that history. “I think the Negro Leagues museum is one of the most important cultural institutions in this country because of the work that we’re doing to save a piece of Americana that was on the verge of extinction.”

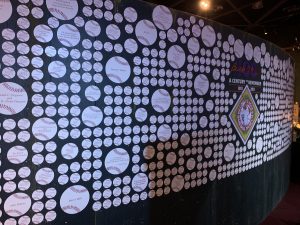

Situated in the historic 18th and Vine district, the museum is not incredibly large at first glance, but, once you step inside you are treated to a world of perseverance and triumph. Built in 1990 the museum occupies 10,000 square feet and features multiple exhibits, several films, hundreds of photographs and a massive collection of baseball artifacts.

While the story is rooted in segregation and the ugliness of America in the early to late 1900s, the museum is anything but sad. “This is a celebration,” Kendrick said. “It is a celebration of the power of the human spirit to preserve and prevail.”

Humble Beginnings & Difficult Moments

The museum is the brainchild of local historians, business leaders and former baseball players. What once occupied a small one-room office quickly expanded in the decades that followed. It now has full-time staff to go along with a board of directors. The museum holds charity events and welcomes dignitaries such as presidents and congressmen.

Sitting at the top is Kendrick, the president of the museum. Kendrick got his start in 1993 as a volunteer for the museum. Before becoming a full-time staffer, Kendrick worked for the Kansas City Star in the promotions department and had the opportunity to promote an event the museum was holding. He fell in love that day. Kendrick later became the museum’s marketing director and held the position for 12 years.

However, much like the story of the Negro Leagues, things have not always been this easy. For several years following the recession, the museum struggled with its finances. Its collapse was certainly imminent.

In 2010, Kendrick left his post, just one year after losing his bid to become the museum’s president. In his place, Greg Baker, a former assistant to the Kansas City manager, took over the museum and crafted a new path that stood in stark contrast to what the museum originally created.

A 2013 article by the New York Times reported that in 2009, the museum lost more than $300,000. In 2010, the museum held its Legacy Awards event in a larger hall with more costly arrangements in an effort to bounce back. The attempt failed greatly.

Betty Brown, a chairwoman of the museum, said at the time “We had never lost the kind of money we had lost that year in putting on the Legacy Awards.”

Baker later resigned in 2010 after coming under pressure.

Getting Kendrick to come home was not an easy task. He had already taken another job for a different sports group. “When I got approached about coming back, I had to really think about it,” Kendrick said. “I had to pray on it.”

While Kendrick distanced himself from the museum he says that the museum itself never left him. “It’s in your heart, in your blood. It’s something we’ve been so inherently proud of building and the work we had done.”

The decision was difficult due to the place the museum was at the time. Kendrick began to wonder what would happen if he could not bring the museum back. “They don’t remember the guy that was there and messed it up,” he said. “They’re going to remember who was there when it bottomed out.”

Kendrick eventually made his decision and elected to return. It required a lot of thinking as well as the blessing from his wife. His decision was also heavily influenced by the late John “Buck” O’Neil, a former Negro League player, manager, the museum’s face and Kendrick’s close friend. Part of the downfall in the museum could be contributed to O’Neil’s passing in 2006. In essence, O’Neil was the museum’s lifeline.

“I’m trying to convince myself every reason in the world for why you shouldn’t come back,” Kendrick said of making the decision. “Every time I did, ‘ol Buck is on the other shoulder saying, ‘Come on back home.’”

Kendrick did just that and returned home some 13 months after leaving. If the museum were to fail, he would live with the results.

Since then, the museum has done anything but fail. Attendance has greatly increased and according to the New York Times, it turned a $300,000 profit in 2012. The sponsors that at one point left have returned.

In 2017, the MLB and MLB Players Association jointly donated $1 million to the museum. MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said at the time, “…It occurred to me that the foundation of our effort with respect to African-American players had to be an effort to make young African-American players understand the Negro Leagues, understand the significance of the Negro Leagues to African-American history and to American history.”

The spirit of the players that envelops the museum, which at one point was nearly lost, has since returned.

“We’ve been able to turn the ship around,” Kendrick said. “We think we’ve just scratched the surface of what this museum can potentially be.”

The museum’s potential is aided by research done by historians that not only preserves a part of history but expands the story as well.

An Unorthodox Historian

Phil Dixon asserts himself as the foremost historian on Negro League and black MLB research. Dixon, 62, has been doing research on the Negro Leagues for well over 40 years. He has written countless books, recorded thousands of interviews and toured hundreds of cities.

Dixon, a lifelong baseball fan, credited his thirst for knowledge in pushing him to pursue history. He had read about the leagues before but noticed a trend in which many books only focused on big-name players. Dixon wanted to change that.

“When I started to do research, I wanted to write about the rest of the people on the team as well as those people they were talking about,” Dixon said. “While that would sound like no great revelation, it was back then.”

When Dixon began his hunt, there was no internet or advanced technology that would aid in his quest. More so, Dixon carried no formal historian education. So Dixon had to get creative in achieving his goal such as visiting towns, tearing out phonebook pages or writing letters.

“I think people feel like they can sit at home,” Dixon said of obtaining information. “Sure you can sit at home and get the census on the computer, but nothing compares with actually rolling your sleeves up and going out and doing the work in the community.”

Recently, Dixon wrapped up a 200-city tour that he began in 2014. His tour took him all across the Midwest and beyond. The tour aimed to improve race relations through the sport of baseball by educating people about the Negro Leagues.

“America is made from all these diverse communities and many people have participated in this great thing called diversity,” Dixon said. “Yet they’ve never been celebrated.” Dixon aimed to change that.

To make the experience more authentic, Dixon drove to all 200 cities in the same way that many Negro League teams traveled to their matchups. His motivation? “A love for the game, a love for people, and a love for the thing that made America great, which is diversity.”

Dixon’s research has not only spurned people in the Midwest to check the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum off their bucket list but has also given people across the United States and beyond a chance to learn about the leagues.

“I hope to leave the legacy of the men who talked to me in the most authentic was possible,” Dixon continued. “…If I can tell their story and get it to the next generation, they don’t die. So far they haven’t.”

While both Kendrick and Dixon have reached success, the museum has not been without its problems.

An Institution Under Attack

In June, vandals cut a water pipe on the second floor of the Buck O’Neil Research and Education Center causing $100,000 in damages. The research center, which is being housed in the Paseo YMCA building where the Negro Leagues were founded, suffered massive damage.

“It broke my heart,” Kendrick said. “We were going to save that old historic landmark and convert it into an education and research center in memory of Buck O’Neil.”

The project began as a grassroots effort that has been ongoing for some time. In 2006, the Kansas City Enshriners coalition of businessmen contributed $50,000 in order to jump-start the project. Another $1 million was pledged by Julia Irene Kauffman, daughter of Ewing Kauffman whom the Kansas City Royals’ stadium is named for.

“You’re ready to give up on people,” Kendrick said after describing the damage he saw that day. “But then you realize you can’t give up on people.”

As Kendrick and the surrounding community reeled, many stepped up to help. Some community members began to clean up, others donated to help with repairs and other associated costs. “You don’t want the hater to have the last word,” Kendrick continued.

Just one month prior to the vandalism, the home of Negro Leagues pitching legend Satchel Paige was set ablaze. And while the incident continued a startling trend, Kendrick will not back away from continuing his mission.

“These athletes never cried about the social injustices,” Kendrick said. “They went out and did something about it.”

The attack on the institution and the incidents that preceded it reaffirm both Kendrick and Dixon’s goal of informing the public and preserving the story.

Keeping the Story Alive

As the president of the museum and the embodiment of O’Neil’s stewardship, Kendrick believes it is his job to take care of a history that has often come close to being lost.

“It’s too important to allow this story to die when that last Negro Leaguer leaves the face of this earth,” Kendrick said. “The Negro Leagues Museum doesn’t need to survive. It has to survive.”

While keeping the story alive is a daunting task, both Kendrick and Dixon operate without fear. Both believe that the work that they have done and will continue to do will allow the story to live on.

“I’ve been able to use the stories to tell a history,” Dixon said. “Even if you are not a baseball fan, you like a good story.”

In sharing these stories Kendrick believes he is revitalizing something that Americans were cheated out of learning. “In doing so, it is poetic justice in its own way,” he said.

And the spirit of “Buck” O’Neil that Kendrick and others try to emulate, it is something that guides those at the museum and something he hopes rubs off and those who come in.

“That spirit is still there, and it emanates and resonates through all of us who work here,” Kendrick said. “We try to welcome people with that same “Buck” O’Neil zest, zeal and spirit. We hope they feel that.”

In showcasing that spirit, Kendrick hopes that O’Neil can live on forever. “O’Neil represents everything great about this country,” Kendrick said. “…He saw change, he was a part of change and he lived long enough to enjoy that change.”

The museum is a living embodiment of that change.

The general public are not the only people to have taken notice of the museum, many MLB players have also joined in.

A must-see exhibit

Many players have made a point to visit the Negro Leagues Museum whenever their team is playing the Kansas City Royals. Of the large number of athletes that pass through the museum annually, Kendrick says, “It never gets old.”

In the past black athletes such as Adam Jones, CC Sabathia and Curtis Granderson have all made the trek to the museum. However, trips to the museum are not just limited to black players. Many non-black players such as Bryce Harper and Ichiro Suzuki have visited. This year, Granderson took his Toronto Blue Jays teammates on a trip to the museum when they were in town.

In 2017, when Jones was berated by racist taunts during a game at Fenway Park, Jones made a point to visit the museum when his Orioles took on the Royals. He then made a donation for $20,000 to support the museum’s efforts. He said, “It’s about the game of baseball, about the Negro Leagues side of it, their point of view—the things that they didn’t have as much as everybody else, the things that they didn’t care about as much as everybody else.”

On the experience of going to the museum, Aaron Hicks, New York Yankees centerfielder, told the New York Post in 2017, “For me, it’s learning about my history…It’s something I appreciate every time I go there.”

Kendrick described the visits by these athletes as a “great time.” Previously, in-season visits to the museum were limited to players competing in the American League, however, interleague play has made it possible for players in the National League such as Harper to visit.

It is the hope of Kendrick that visiting players walk away with a greater appreciation for the game of baseball. “It’s all about perspective and I think we help them gain a better perspective,” Kendrick said. “And I hope a greater appreciation for those who proceeded them.”

In turn, the museum not only appreciates the boost in popularity it receives whenever a player drops by but the spread of the larger story at hand. “We want players to experience this and I hope build an affinity for what this story represents” Kendrick finished.

The Future

The museum is currently working on restoring the John “Buck” O’Neil Education and Research center. The project is something O’Neil said was “more important to me than any Hall of Fame.”

Recently, the museum held a three-day birthday celebration in honor of O’Neil’s 107th birthday. The three-day event included a fashion show, concert and gospel salute. Proceeds from the event went on to support the museum’s efforts.

The museum will also benefit from proceeds garnered through the MLB’s Winter Meetings auctions that are currently taking place.

As for Dixon, he is working on another book featuring stories from his 200-city tour. He also hopes to visit areas that he was unable to reach such as California and Florida. “As long as I’m able to I’m going to continue telling this story,” he said.

Finally, while the museum is focused on its larger goals, it is ever committed to its primary goal: to inform.

“The Negro Leagues teaches us that in this great country of ours if you dare to dream and believe in yourself, you can do and be anything you want,” Kendrick concluded.

If you go:

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

1616 East 18th St.

Kansas City MO. 64108

More information at https://www.nlbm.com/s/index.cfm