Growing up as a first-generation Latina wasn’t easy for Evelyn Ramirez.

By age 12, she already knew how to file taxes. Her parents, always working, expected her to be a second mother to her younger sibling, complete a long-list of household chores, do well in school, and be a role model for her family.

“At that point I knew a part of my childhood was gone. I had to grow up and mature so much faster than other kids my age,” said Ramirez.

Now 22 and attending University of California, Irvine, Ramirez realizes these pressures contributed to her struggles with chronic depression, something she hasn’t discussed with her parents.

Ramirez says there’s a lack of communication in her family. Although she knows they love her, it has always been a struggle to open up about her feelings.

A sense of overwhelming pressure from home is a common theme among first-generation Latinas, particularly those who are the first in their families to attend college. Yet, there are few services targeted specifically for them.

According to Veronica Obregon, a professor in educational psychology at California University, many are also reluctant to reach out for help.

“Research has shown that Latinx don’t utilize mental health services as much as other populations,” said Obregon. “There’s still very much stigma around it.”

Statistics show why this issue is such a concern.

Young Hispanic women have one of the highest attempted suicide rates in the nation.

In 2017, 10.5% of Latinas between the ages of 10-24 attempted suicide.

A Deeper Look Into Childhood Trauma

The pressures first-generation Latinas face don’t disappear with time. They only get harder to navigate.

Catalina Lara, a 50-year-old first-generation Latina and mother of two, says talking about her childhood is still too raw.

The first time we speak and I can sense her hesitation over the phone.

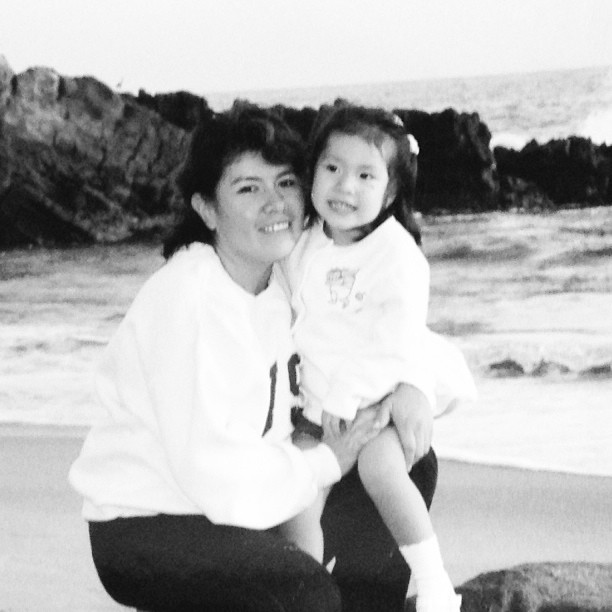

I tell her I’m a 22-year-old first-generation Latina myself, and I begin to share stories of my own childhood, especially my mom. I explain the strict rules she would enforce from a young age, the expectations to maintain a certain appearance, and how her love was shown through actions rather than words.

As I start to talk, I question whether my words will seem foreign to her. I realize my mom is only ten years older than her. Is there too much of a generation gap? Will she be able to relate?

Within a matter of minutes, she starts relaying similar stories of her childhood.

Lara reiterates there wasn’t a lot of communication growing up.

“Honestly, there was not a lot of me talking,” Lara admitted, “As of 12-years-old I fell into the mindset that [my mom] didn’t understand. Anytime I would try to, she would not say the things I expected her to say.”

She believes her relationship with her mom was typical to that of other first-generation mothers and daughters.

“It was just a lack of understanding and on my mom’s side I don’t think it was deliberate. I think she just couldn’t put herself in my shoes. She just couldn’t,” Lara said.

She tells me how she would never ask to go out because the answer would always be no, how the expectations for her and her brother were drastically different, and how critical her mom was of Lara’s actions and appearance.

“I was talking to someone today who was telling me her mom never said “I love you” and I was just like yeah that’s not a thing. They show by what they’re providing for you, and that’s just such a cultural thing,” Lara concluded.

We both understand our moms loved us. More than they could put into words, in a literal sense. We speak about our mothers with lightness. In both cases, they were trying their best to raise us in a new environment.

“I did respect my mom and appreciate a lot of what she did for us because she did do a lot, she did whatever it could to get us into programs and would take us to museums and the library…” says Lara. “She was trying to do better than her mom. Maybe if we had been in Mexico it would have been different.”

At the end of our conversation, despite the seriousness of what we have discussed we both can’t help but laugh at the similarities between our childhood.

I’m reminded of the “Latina Mom Memes,” I see on social media a little too frequently.

The ones where the mom is calling her daughter fat, threatening to call the cops on her for coming home late, or forbidding her to go out until she cleans the entire house.

The thing is, these memes are funny. The humor comes from being able to relate to them. But do they also call attention to bigger underlying issues that are difficult and painful to process?

Obregon believes they do.

“We need to identify what are our cultural values here and what is really trauma,” Obregon said. “A lot of what you see, a lot of the verbal and physical abuse is not cultural, what we’ve been doing is passing off trauma as culture.”

Trauma that has worsened by poverty and racism and passed down from generations.

As a first-generation Latina, Obregon says going off to college only made problems worse. She was expected to go back home regularly during her time as a student.

“My parents wanted to constantly be supervising me. It was a challenge growing up individually,” Obregon said, “It was a lot of pressure on me. I had these expectations from my family but also high demands at school to perform well and complete every assignment. I couldn’t do both.”

Obregon vividly remembers one night being woken up by the sound of her mother banging on her apartment door.

“I remember being really scared not knowing who it was. I asked her, ‘Why are you here? Why are you doing that?’ and her response was ‘I’m angry at you because you’re not answering your phone,’” Obregon laughed as she vividly recalled the story.

She believes first-generation parents don’t really understand the requirements of college. Having not attended, they don’t know what the workload is like or how rigorous their child’s schedule can be.

A study on first-generation students and their use of counseling services at universities showed they often face additional family, cultural, social, and academic challenges.

“First-generation students tend to have lower ratings of sense of belonging and satisfaction that non-first-generation students,” the authors write. “We found that sense of belonging is significantly related to mental health […] first-generation students have a higher frequency of reporting feeling stressed, depressed or upset.”

Many first-gen Latinas, like Ramirez, hope going off to college will help them escape the pressures at home. But in most cases, family-related pressures follow them to campus.

“I feel guilty that I’m not home and instead focusing on academics. It makes me feel selfish for wanting that for myself,” Ramirez admitted.

Ramirez says her time away from home has allowed childhood memories and experiences to resurface. She says a lot of the negative emotions she felt growing up, not only within her family but in her school and community, have only amplified over time.

“As a kid, I kind of felt bad about being Mexican. The city I grew up in made me hide my background,” Ramirez said.

“I had to suppress my own culture because I felt like I had to fit into these norms and fit in with the other students that were white. I would think to myself ‘Okay, this is white Evelyn now and she has to be present for academics.’”

Ramirez learned to keep to herself in classes. She would do her work, pay attention to lectures, and then pack up and leave without speaking a word to anyone else.

She says it wasn’t until this year, while taking a Latinx/Chicanx class at UCI, that she realized many other Latinx students shared the same pressures.

Being surrounded by a new community has pushed Ramirez to join groups like the Latin American student organization and SAFIRE (Students Advocating for Immigrant Rights and Equity).

UCI was recently designated as an HSI (Hispanic Serving Institution), which means at least 25 percent of students enrolled full-time are Hispanic. In turn, these institutions are eligible to compete for HSI-related federal funding.

Ramirez feels that UCI could be doing more to help the first-generation Latinx community on campus, specifically when it comes to mental health.

UCI did not respond to requests for comment.

Another HSI, University of California, Davis has set initiatives to provide more funding for Latinx mental health on its campus.

According to the website, UC Davis is actively trying to respond Hispanic mental health demands by increasing counseling services in student centers and housing locations, hiring new culturally specific counselors, facilitating easier access to healthcare providers, and creating a wellness program that other UCs can implement.

Other universities, like University of Southern California, are beginning to make efforts to serve the mental health demands of the Latinx community. While resources are not yet available specifically for first-gen Latinas, there are Latinx therapists at the student health center ready to help with culturally specific needs.

LA CASA, a Chicanx and Latinx community on campus, has been holding a Power Pan Dulce series where they bring in alumni, professors, and external resources to talk about pressing issues in the Latinx community.

The last event specifically addressed childhood trauma.

Billy Vela, director of LA CASA, says a lot of the problems Latinx students are facing are coming from childhood issues that haven’t yet been resolved.

“We’re always trying to see what else we can be doing to help,” Vela said, “if something isn’t working, we try something new. We’re not there yet, but we’re really trying to bring people together.”

“It’s about feeling like you belong. That’s it. A lot people don’t feel like they belong, they don’t find their community. Once you feel like you belong, you’re going to start to do the work, in a community,” said Vela.

A Brighter Future

Now with two teenage daughters of her own, Lara is doing everything she can to make sure she can be the best mother to them.

She has attended therapy sessions, several with her mom, to heal childhood wounds and stop the cycle of unintentional trauma from continuing onto her children.

Lara has also created a workshop for first-generation moms.

“Educating mothers is extremely important,” Lara said. “We talk about our experiences as first-generation Latinas, we look at statistics, and we really think about what we can be doing to support our children, especially when they go off to college.”