My first pair of colored contact lenses was purchased inside an accessory shop in Koreatown. A middle-aged Korean clerk convinced my then-teenage self to fork out $30 for hazel contacts that would lighten and “enhance” my eyes. Actually, he didn’t have to do much to convince me. A YouTube video had already persuaded me.

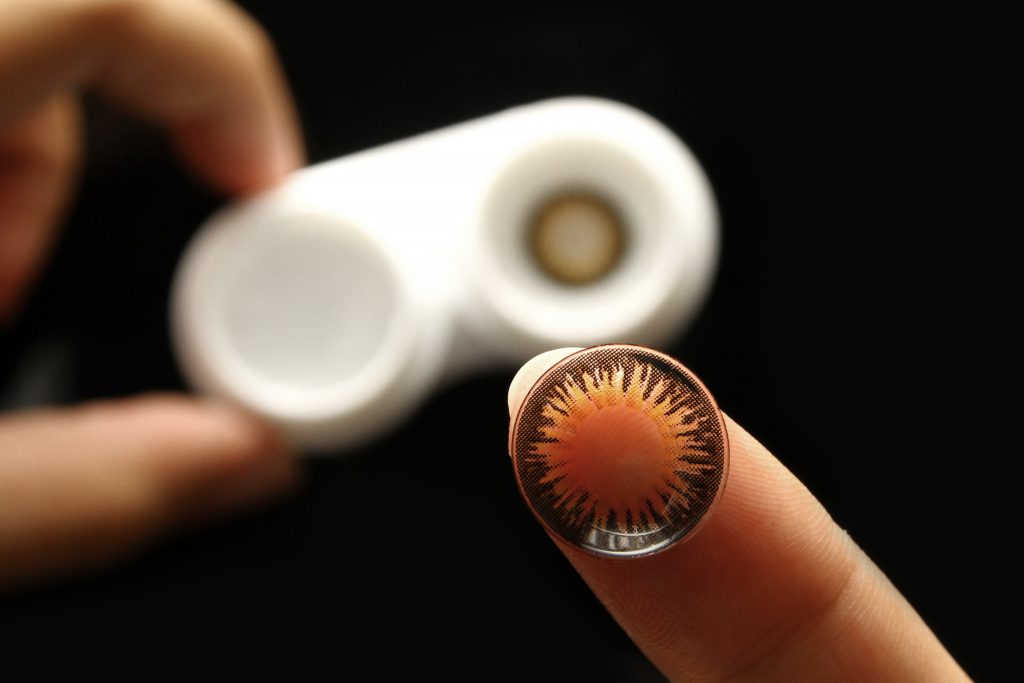

In 2010, Michelle Phan — now considered the pioneer of beauty YouTube — uploaded a viral recreation of Lady Gaga’s makeup in the Bad Romance music video. Around the video’s six-minute mark, Phan popped in a pair of gray circle contacts, blinking rapidly as her eyes morphed into an unnatural, doll-like shape. Circle lenses, which are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, create the illusion of larger eyes through color patterns on the iris. “See how big they look now?” reads a caption in the video.

The cosmetic lens fad began more than a decade ago in Asia, and through YouTube, blogs, and online forums, the trend proliferated — spreading among young women and cosplayers, people who dress up as characters from pop culture. Months after Phan’s viral video, the New York Times published a story on the risk behind eye-enhancing circle lenses, which are not approved by the FDA.

(The FDA requires vendors to register products on its site before they can be commercially distributed; it’s a process overseas vendors can afford to neglect since their businesses don’t rely solely on American customers.)

Widespread concern over these unregulated lenses subsided over time, but every year, the FDA, Federal Trade Commission, and American Academy of Ophthalmology remind customers to be wary of purchasing colored lenses without a prescription, usually around Halloween. They warn of the potential for severe eye infections and even partial blindness. Luckily for me, I didn’t seriously injure myself. While I was told they would last me a year, I threw out the contacts after a few months because they dried out my eyes and I have been skeptical of them since.

Within the past two years, there’s been a subtle resurgence of colored contact lenses from overseas vendors with whimsical names like TTD Eye, Ohmykitty4u, Uniqso, and Pinky Paradise. They cater to specific customers: TTD Eye is popular among beauty influencers who prefer lenses in striking shades of hazel and gray, while Uniqso is a haven for cosplayers who aim for vibrant, distorted-looking circle lenses.

Since it’s 2019, the marketing platform of choice is now Instagram instead of YouTube. And these contacts aren’t just worn by beauty gurus, makeup artists, and micro-influencers trying to become big-name influencers, but also your regular consumer.

On Instagram, vendors command a network of hundreds of thousands of followers built on sponsored posts and affiliate marketing. Companies scope out lifestyle and beauty influencers for affiliate partnerships, offering them free lenses and the potential to earn am commission in exchange for a post or a video.

Others have more lax standards for their influencer-like partnerships, requiring only a blog or an active Instagram account to promote products. But for the most part, these partnerships and products appear to be unregulated online, creating a free-for-all marketplace where a contact lens brand’s popularity dictates consumer trust.

When Caitlin Alexander ran an alternative fashion blog in 2015, she cycled through five different pairs of circle lenses a week, with colors ranging from electric blue to mustard yellow. It was a rebellious habit, one she stopped shortly after a pair of “bad contacts” severely impaired her vision for a day.

She had worn a pair of soft pink lenses from Uniqso, a vendor from Malaysia, for eight hours the day before (as she usually does) and woke up with eyes that were extremely sensitive to light.

“When I took those pink contacts out at night, my eyes were slightly blurry,” the 28-year-old recalls. “But the next day, I couldn’t even look at any light source and couldn’t see right for a few hours.”

Colored contacts aren’t necessarily harmful; there are federally regulated brands like Freshlook, Air Optix, and Acuvue that require a prescription to obtain. Contacts sold from overseas vendors are comparably cheaper and can be bought as singular pairs. Lenses retail for as low as $15 a pair before shipping costs, but prices vary depending on the contacts’ length of wear, prescription, and brand.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19293517/pink_contacts_sig_ii.jpg)

Interested lens buyers tend to congregate on online forums or blogs and discuss which vendors are most reputable and have the best prices. Some are wary of brands that don’t verify a customer’s prescription or ones that take weeks to ship out an order.

Still, the problem with purchasing decorative lenses online is that there’s such a vast marketplace of options that some products — especially ones that can be obtained without a prescription — might not be tested as safe for use.

As a 2015 study in the Journal of Forensic Sciences found, a product’s safety depends on how it’s manufactured and the chemicals used in the process. Since there are so many lenses available, the study concluded that optometrists should be skeptical about the quality of most colored lenses.

A lens prescription typically comes with a specific set of parameters, says Mike Shea, an optometrist in Connecticut. Even if customers order decorative lenses online according to their prescription, there’s still a margin for error when it comes to the contacts fitting properly. With colored contacts from overseas vendors, Shea adds that the bigger issue is sterility and cites the 2015 Journal of Forensic Sciences study.

The study, which was conducted by researchers from Japan’s University of Tokushima, examined the safety of the chemicals used to tint five different colored lenses. The lenses were “obtained arbitrarily without a prescription” online or at a pharmacy, and varied in design and color pigments. The researchers discovered that the colored chemicals within these lenses could be exposed to lens wearers, putting them at risk of corneal infection. And based on the vast market of colored lenses available, it’s difficult to pinpoint the overall risk.

Alexander later emailed Uniqso to ask for a refund, but before the company issued her a replacement pair or a refund, a customer representative told her to cut the defective lenses in half, according to a screenshot of the exchange. In 2016, a year after the incident, Alexander decided to write a blog post detailing her interactions with Uniqso and her decision to stop promoting the brand.

It took her a year, Alexander says, because she was convinced she had worn the lenses wrong or that it was an isolated case.

“Shortly after I published my blog, people accused me of not knowing how to put contacts in or trying to make Uniqso look bad,” she says. But years later, Alexander still receives comments and emails from people who’ve had similar issues with their lenses.

“I don’t really play games with my eyesight anymore,” Alexander tells me. “I just wear prescription glasses.” Despite her cautionary blog, she’s still worried that many customers are too trusting of online lens vendors, especially “young impressionable people” who trust influencers’ reviews.

“I don’t really play games with my eyesight anymore”

Caitlin Alexander

“People believe that influencers have their best interests in mind,” she says, but no one takes into account that these influencers aren’t health professionals. “I’m sure they do, as I did.”

Colored lenses have become ubiquitous — at least according to my Instagram algorithm. They pop up in selfies, photoshoots, and makeup tutorials. There is one type of video that keeps showing up on my Instagram Explore page that is eerily similar to Phan’s: A beauty influencer holds up a colored contact lens on a plastic applicator, concealing her face. She quickly inserts one, then two lenses before blinking at her online audience.

These short “try-on” videos are pulled from a playbook of social media marketing tactics used by lens vendors. Most of them are based in Asia, where cosmetic lenses originated, and very few require customers to verify their prescription before purchasing.

Most vendors do not manufacture lenses, but they are still the middleman — responsible for sourcing products and ensuring their safety and usability before shipping them to customers.

Pinky Paradise, a vendor in Malaysia, was the only company out of the four I contacted that responded to my questions and confirmed that it checks prescriptions before processing an order. It’s also one of the only overseas vendors I’ve seen that requires customers to submit their prescription before ordering. (Having this process in place doesn’t necessarily mean that a vendor’s products are registered with the FDA.)

According to Pinky Paradise founder Jason Aw, the company carries a variety of brands from Korean manufacturers and sources products that meet Korean and international health standards.

“We wouldn’t sell any products that were not approved by high-standard legislation certification,” Aw wrote in an email, adding that Pinky Paradise has been in the lens business for more than a decade. Most Korean manufacturers are focused on getting approval from European and Asian regulatory bodies, he added. When I asked Aw about his competitors and how they don’t seek out prescription verification, he declined to comment.

“We just want to make sure that on our part, we are doing it right and safe,” Aw wrote. “But as a vendor too, we do think that complying with the regulations is necessary in the long run.”

E-commerce platforms have made it quicker and easier to purchase illicit lenses, says Barbara Horn, president of the American Optometric Association. Before these platforms, it was easy for regulators to track down illegal sellers in brick-and-mortar shops, like gas stations and corner stores, and fine them for violating the law.

In recent years, the AOA, FTC, and FDA have directed their efforts toward Amazon and eBay, Horn says. But Instagram is a tricky turf to regulate, especially if vendors aren’t selling directly from the platform.

An FDA spokeswoman told me that the agency has staff “who communicate regularly with these online vendors and work to make sure devices that are misbranded or adulterated are appropriately handled.” She offered examples as to how the FDA has fined and even jailed illicit American sellers who’ve imported and resold counterfeit lenses from Asia.

Still, the FDA and the optometrists’ association offered no concrete solutions that would curb how decorative lenses are sold and marketed online, specifically through incentives like discount codes and free giveaway items. The bigger question remains: Are customers aware of this risk? And if so, will they care enough to stop buying them?

When I spoke to influencers who promoted these lenses, they told me that they chose to partner with vendors that seemed reputable. But on Instagram or YouTube, a brand’s reputation among potential buyers is typically cemented by influencer promotions. Buyers and even other influencers are often introduced to a company through its social media presence and who chooses to work with the brand.

Keiana Quallo, a 24-year-old YouTuber from Queens, New York, had only worn colored contacts purchased from a boutique shop for an old Halloween makeup tutorial. She hadn’t considered using lenses again until TTD Eye, a Hong Kong-based vendor, reached out to her. The brand’s diverse color selection and complementary effects on darker skin tones made her want to work with the company.

“I do tons and tons of research, especially with contacts,” she says. While she’s heard “horror stories” about some lens companies (“Not from any specific company but more in general,” she says), Quallo claims that TTD Eye is a tried and tested brand.

“When it comes to the beauty community, even with makeup, you have to do your research and trust your gut,” Quallo says, when I asked about the lack of federal regulations around decorative lenses.

Among the Asia-based lens retailers I looked into, TTD Eye was the most popular, boasting more than 600,000 followers on Instagram and a sweeping network of affiliate partners — influencers who are given a specific discount code to promote a product in exchange for commission brought in from that code.

Influencers are a loose description; a number of TTD Eye’s affiliate partners have less than 10,000 followers on Instagram. In addition to scouting for influencers, some brands like Uniqso allow people to request to join the affiliate program. TTD Eye did not respond to multiple emailed requests for comment.

“When TTD Eye reached out, I had around 5,000 followers,” says Tania Kwok, a 19-year-old New Zealander who runs the makeup Instagram @luciphyrr. “By the time the lenses came, my account had grown considerably.”

Kwok now has more than 36,000 followers, an increase she attributes to posting frequently and Instagram’s algorithm updates. She was previously contacted by a less popular contact lens brand, which she turned down because she didn’t trust its products.

Kwok explains that she “inherently trusts” TTD Eye since popular models and influencers have worked with them before. She describes the brand as “the fast fashion of colored contacts.”

Cosplayers and popular users on TikTok have also started to endorse TTD Eye on the platform, but a number of people have spoken out against the brand’s safety, claiming that its contacts have caused eye damage. Several have claimed that the contacts affected their corneas, and are encouraging others to not promote or wear products from the company.

The lens craze has “crept up” on the makeup community, according to Kwok, since lens sponsorships can appear more subtle than a fashion advertisement. When artists post their makeup looks on Instagram, it’s a common practice to list the products used to achieve the final result and tag the respective companies. And sometimes, colored contact vendors are tagged in that list, featured along with an artist’s discount code for lenses.

While the FDA and FTC have cracked down on illicit vendors, sponsored content plays an indisputable role in attracting customers to these unregulated products. Still, regulatory agencies don’t “attempt to survey all influencers or influencer posts, either alone or with social media platforms,” according to the FTC Advertising Practices Division.

As Suzanne Zuppello wrote for The Goods, “social media is an advertising black hole with limited tools to search and report non-compliant posts.”

Vendors that use a network of little-known influencers to promote their lenses are even less likely to receive scrutiny, especially if they’re touted as a decorative or cosmetic product. These posts are more of an endorsement rather than an ad, since influencers aren’t getting paid to post about the lenses. Their commission comes from the number of people who use their discount code in their purchase.

After going down a rabbit hole of videos and photos about colored contacts, I decided to purchase a pair of hazel lenses from TTD Eye in September. (I didn’t need to submit a prescription.) They cost $24.50 and would last me a year, according to the package — a bargain compared to my annual haul of clear two-week lenses.

What caught my attention wasn’t the lenses themselves, but a note printed at the bottom of the box that came with it.

“You win the special coupon code for 10% off,” it read. “Share this code to anybody who [sic] interested. If the code is used five times, you can win one pair of lenses.”

I’m not an influencer; I’m a consumer. That didn’t seem to matter to TTD Eye. Its strategy relied on attracting new customers from the social circles of its existing buyers. It’s a shrewd business move, which makes use of the trust people place in who’s recommending them the product.

Trust, as we’ve seen time and time again, can be exploited by influencers and companies for their bottom line. In this case, it’s even more nefarious. Influencers and even average consumers are promoting unregulated lenses, which are medically dubious at best and, in some cases, a serious health hazard.