The 3400 block of Olympic in Boyle Heights is busy on Tuesday mornings. Cars are packed with stressed parents and angsty teens zipping to get to school on time while the acapella battle between the neighboring auto body shops is in full swing of who can sing louder to Juanes between every sharpening tool being ignited.

Positioned between the chaos of horns, sirens, and cursing auto body workers is Raul Ortega’s food truck.

Wedged between two cars, this all-white truck printed with Christmas-colored font that reads in capital letters, “MARISCOS JALISCO,” has been parked across from the Lou Costello Jr. Recreation Center for the last two decades.

On the truck, Ortega is removing the tortilla shells from the crackling oil. Stuffed in these hot, fresh, corn shells is a buttery blend of fresh shrimp and vegetables. Ortega shuffles to the right of the prep line, places the two crispy shrimp tacos on their styrofoam plates, lathers on five shavings of fresh avocado, and ladles a generous pour of fresh salsa on top of the tacos. The salsa is perfectly situated between a chunky pico de gallo and smooth red salsa. With the second pour of salsa, it is impossible not to notice the red and blue ink inside of Ortega’s forearm that reads “MARISCOS JALISCO.”

Ortega’s love for food and his empire is evident beyond the tattoo but also by the taste of the crispy shrimp taco. From the crunch of the flakey-corn shell to the butter shrimp mixture with the tanginess of the salsa, customers are constantly returning to the window to buy yet another taco, for $2.50.

Ortega’s journey begins in his hometown of San Juan de Los Lagos in Jalisco, Mexico. After migrating to the U.S. at 18-years-old and then permanently relocating to Los Angeles at 23, Ortega has worked at a variety of jobs before entering the street-food industry.

“I worked everywhere and did anything just to make a buck…I was selling CDs and movies on the streets…I used to buy cars from different sites…I was just trying to make a living out of anything,” said Ortega.

That entrepreneurial mindset is the root of Ortega’s success. After returning to what he knows and loves best—food—he invested himself into what he knew people would like: authentic Mexican food.

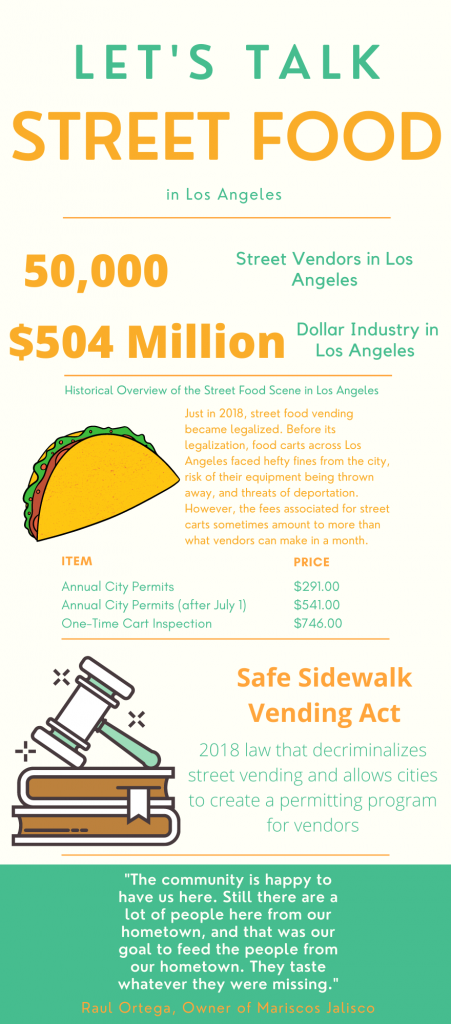

“The community is happy to have us here. Still there are a lot of people here from our hometown, and that was our goal to feed the people from our hometown. They taste whatever they were missing,” said Ortega.

Ortega’s first truck on Olympic quickly grew to three different trucks and one restaurant in different parts of the city, after gaining national recognition from a feature in the esteemed Jonathan Gold’s “101 Best Restaurants in Los Angeles.”

“Every time he wrote about us there were waves of people who I would never think would come to a food truck. He changed the perspective [of street food] for everybody,” said Ortega.

Ortega summed up the attitude shift towards street food that a lot of food experts and writers have witnessed in the last decade. There are around 50,000 “microbusinesses” located down every street block in Los Angeles that sell everything from fresh fruit to birria style tacos to tupperware and belts (Next City). This compilation of street vendors makes up the exponentially growing industry that accounts for $504 million annually (Next City). Street vendors, specifically food vendors are only gaining in popularity.

Farley Elliott is the Senior Editor at Eater LA and the author of “Los Angeles Street Food: A History From Tamaleros to Taco Trucks.” Elliott has witnessed the evolution of street food and hopes people continue to have an open attitude towards the industry.

“I am really looking forward to the day when vending is seen by diners as a viable way to spend an evening, not a stop off or it’s 3 a.m. and ‘I was the bar before,’ but a real opportunity to sell to people of all classes in all neighborhoods at all price points,” said Elliott.

Having esteemed writers like Jonathan Gold, Farley Elliott, and a host of other bloggers, Instagrammers, or Tik Tokers post and share their experience about that taco truck or fruit cart in different parts of Los Angeles exposes people, who wouldn’t normally try that food, to another culture, story, and region of the city.

“We are not talking about the boiled hot dogs in Midtown Manhattan, we are talking about regional food in every corner of Los Angeles that cater to serve the communities in which they are located. You may be a participant in a small way to a street food stand or tamale vendor but that isn’t to say they are for you or belong to you, but that is part of the beauty that they are meant to serve communities that you wouldn’t normally interact with anyways,” said Elliott.

Getting people to venture into different areas to try those foods that are out of their comfort zone already brings its own host of obstacles.

The life of a street vendor, specifically a street food vendor has not always been particularly easy. From Ortega’s personal experience, one councilwoman was very against street food vendors to the extent that she made him move his truck every 30 minutes until he brought the case to court and won.

Street vending was not legalized until 2018, which means city officials and workers up until three years ago were being kicked off that street, having their grills confiscated, harassed, charged fees, and forced to close.

According to Sarah Portnoy, a USC Professor and expert on Latino food and food justice, explained that before the vending act was unanimously approved in 2018, vendors were “ticketed, abused, and stripped of their merchandise.”

The fees associated with purchasing a street and health permit, taxes, and other city fees for being a street food vendor are expensive.

“Some of it isn’t realistic, to buy city permits and county health permits account for well over $1000 dollars and if you’re someone living paycheck to paycheck it can be a lot of money,” said Portnoy.

The reason for this tension between city officials and street vendors is for multiple reasons. Some of the reasons include street vendors are looked at as “eye sores,” there’s been a rise in gentrification, and the brick-and-mortar businesses and Small Business Association feels like they are paying “greater overhead in terms of rent and other associated costs” than the street vendor parked out front, according to Portnoy.

Like Ortega, a majority of street vendors are immigrants. Even though street vending has been decriminalized, Portnoy explained the difficulties for these micro-entrepreneurs.

“If you don’t speak English, you don’t have papers, or the cultural knowledge to know how to do things, your economic opportunities are limited,” said Portnoy.

Despite the obstacles, Ortega has no plans of closing anytime soon.

“I love my job. I get to meet new people everyday…and get satisfaction from the loyal customers and everything that comes with it. I am so proud,” said Ortega as he flashes his arm tattoo brandishing the name of his self-built, street taco empire.