When Frankie MacTavish first started go-go dancing — as a 21-year-old in 1989 — he never expected it would lead to him being a witness in a courtroom. But when the Los Angeles Police Department’s Vice Division raided the fetish club he was performing at in 1993, that’s just what ended up happening.

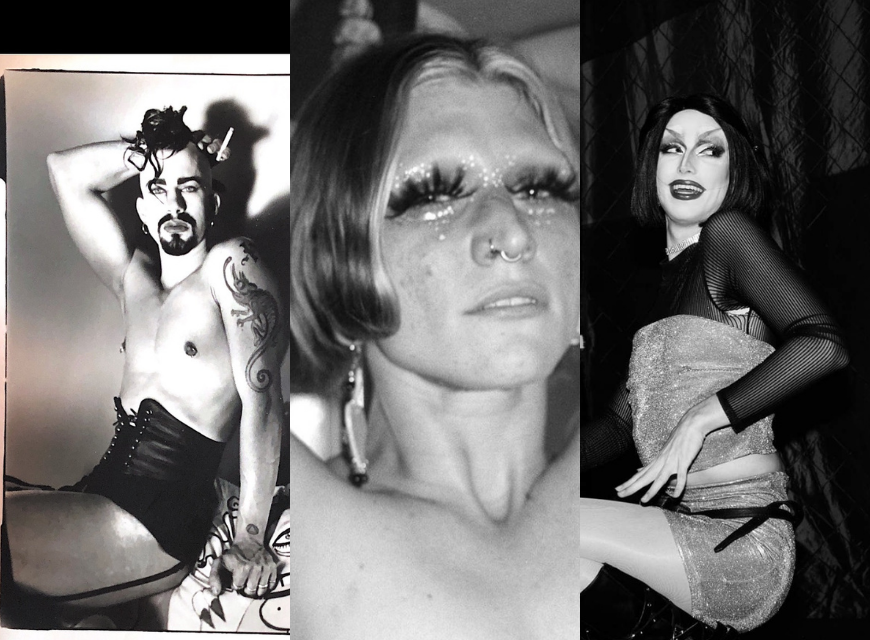

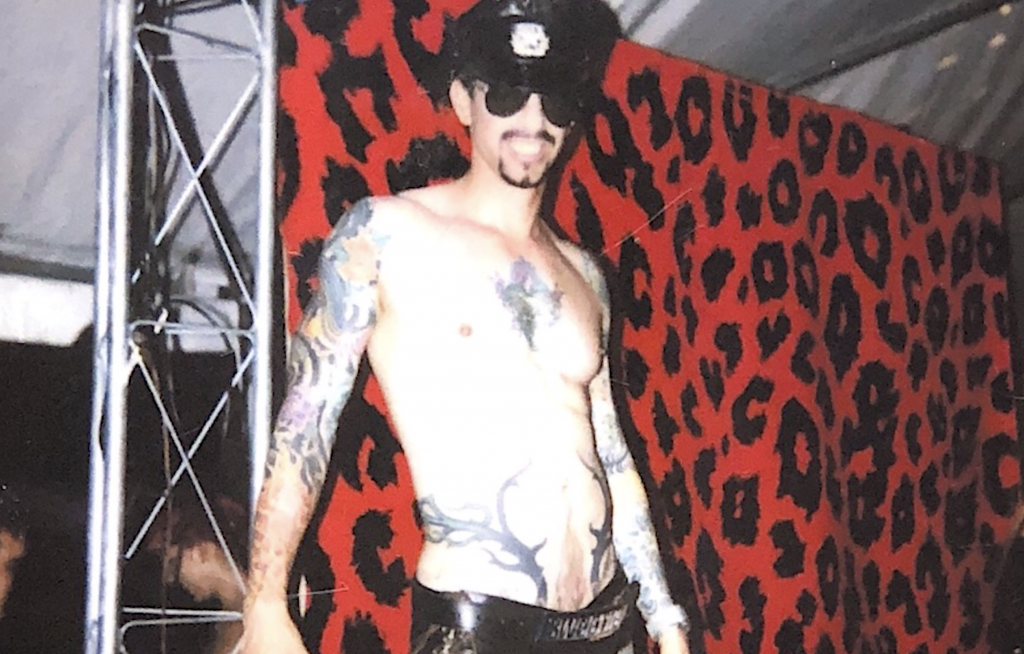

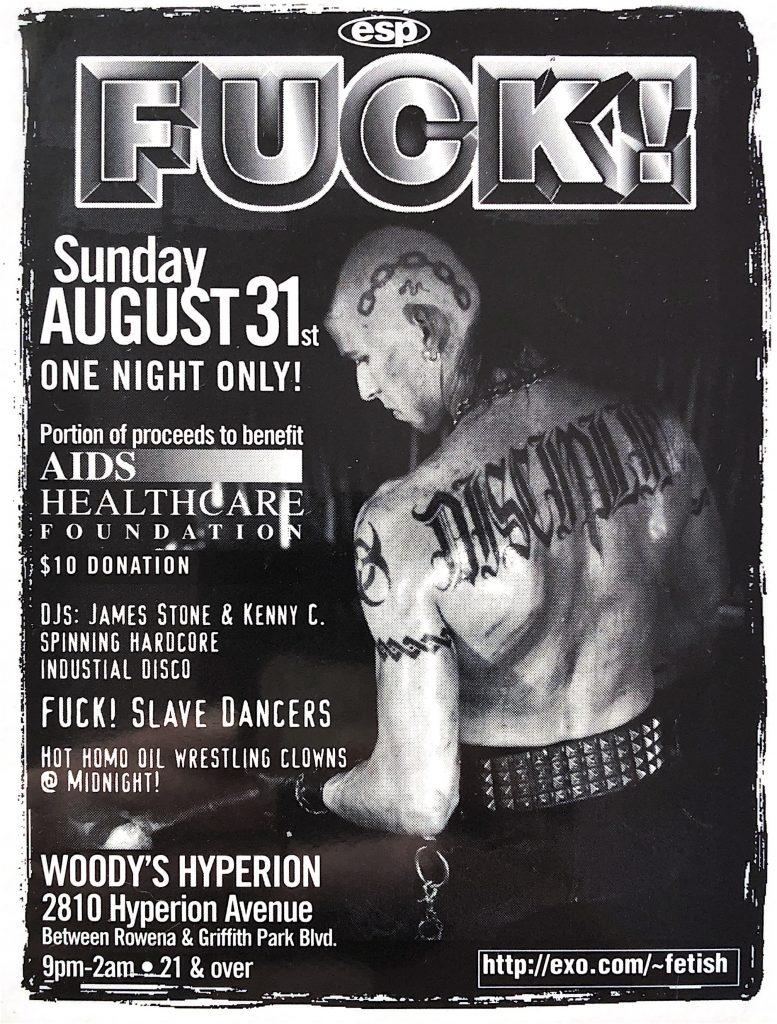

The nightclub, first based at Basgo’s Disco in Silverlake, then at the Dragonfly in West Hollywood, had a name most newspapers wouldn’t even print in full: Club FUCK! According to MacTavish, now 54, the name had less to do with sex, and more with, “fuck what the establishment thinks of us.” Held on Sunday nights, the weekly party had everything, from live piercing and body modification acts to legendary performance artists, drag queens and go-go dancers like MacTavish. It was a revolutionary space that accepted freaks and queers wholeheartedly, and mirrored similar queer punk movements happening in New York and London around the same time.

By the spring of 1993, the club had gained some mainstream popularity, with write-ups in the L.A. Times and Vogue, and was beginning to attract more patrons from outside the fetish scene to which Club FUCK! catered. One of these “outsiders,” put off by the extreme nature of the club, called the police to report what they had seen, according to the ONE Archives, USC’s LGBT library. MacTavish said he jumped down from the box where he was go-go dancing in time to avoid arrest, but many of his friends didn’t. He ended up being called upon as a witness in the courtroom, with the prosecution asking him whether he saw one of his friends putting his fist inside another dancer.

“And I just said, ‘Could you repeat the question?,’” MacTavish said, “because it was so preposterous that [he] would be fisting [anyone] at the club. That type of thing didn’t happen.”

Following his lawyer’s advice, MacTavish told the truth about the goings-on at Club FUCK!. They were certainly provocative, but always in the name of art and spectacle. Along with the rest of the dancers, he was able to avoid any lewd conduct charges on the grounds that patrons at the bar knew what they were getting themselves into.

“So it eventually got thrown out, which was great, and we had a big celebration and a party,” MacTavish said. “But yeah, we were all really scared that we were going to have to sit with like, you know, sexual misconduct or, you know, those kind of charges that come and stick with you.”

Such charges, and often more serious ones, were common at one point in history for queer people who were simply trying to enjoy a night out in Los Angeles. In fact, one of the first documented LGBT protests against police brutality, before the Stonewall Inn in 1969, was at the Black Cat Tavern in 1967, after undercover police officers arrested more than a dozen men for “public lewdness” for kissing on New Year’s Eve. (Two of those men were forcefully registered as sex offenders.) The Black Cat Tavern eventually became Basgo’s Disco, which is where Club FUCK! was founded.

After the trial, Club FUCK! was forced to shut down for good, and MacTavish continued dancing at other venues like the popular Club Cherry on Fridays, and fetish club Sin-a-matic on Saturdays, both in West Hollywood. It’s hard to describe the nature of such venues, which were unlike anything the city had seen before. One L.A. Times article from 1991 about the latter club wrote, “In one advertised and heavily attended spectacle, a large crowd watched a drag queen cover a young man’s bare feet with whipped topping and pancake syrup and lick them clean.”

Joseph Brooks, who created all three of those clubs and many more in the ‘80s and ‘90s, said he was less concerned with the law and more interested in bringing Los Angeles a new club scene inspired by the London punk scene. He moved to LA in 1978 from Northern California, first opening a record store and then beginning to host parties around the city.

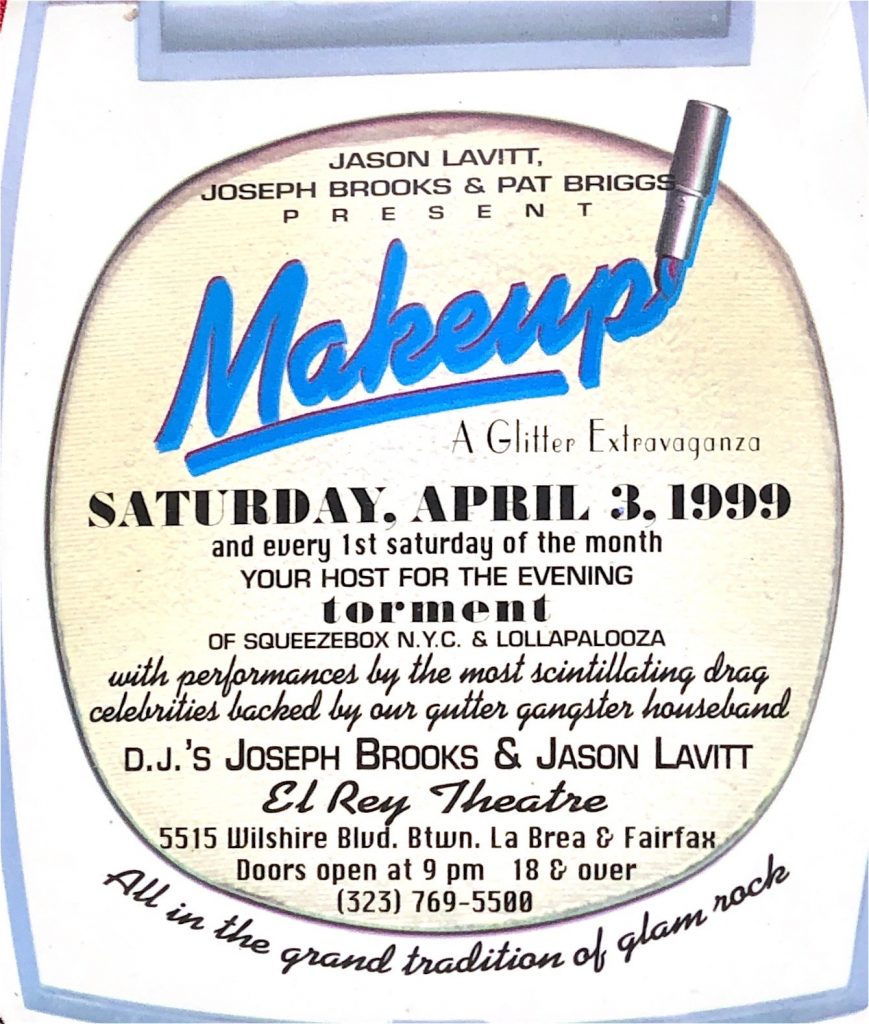

Iconic performers came through the ranks of his clubs, including the world-renowned burlesque artist Dita Von Teese and Raja, the winner of the third season of “RuPaul’s Drag Race.” Brooks said he never had any run-ins personally with police, and he left that responsibility to the bar owners, who were responsible for the liquor license. His job was to make the flyers — and change the culture, as well.

“We were completely not interested in reproducing what was going on in other places,” Brooks said. “We were trying to do something that was special and unique and served an audience that was special and unique and on the edge and not mainstream, and I think we did a brilliant job.”

Brooks said at first he wanted a space to play the music he wasn’t hearing at other clubs, like Depeche Mode and The Chemical Brothers. Once the music was playing, the people came. And those people were usually queer and interested in the same things he was, like performance art and body modification, both of which featured heavily at his events.

“People would freak out,” Brooks said. “Ron Athey would do piercings at the club. People would be like, “What the fuck?” But now you know, you can go to a mall in Idaho and get that, you know? It was just trying to do things fresh and new and keep doing that … keep moving it forward. The music changed, what we did changed, the performances changed. We tried keeping up with the times, and we did.”

Frankie kept his act fresh, too. He said he was always trying to “reinvent the wheel” when it came to his performances, and he started doing drag by the name “Aneeda Fix” just to “mix it up.”

At one of Brooks’ events in the late ‘90s, Club Makeup, MacTavish hired an ambulance driver for a “publicity stunt.” The emergency vehicle pulled up outside the club, sirens blaring, and MacTavish was carried through the crowd on a stretcher before getting on stage to sing live in drag, covered in syringes and glitter. The whole thing was filmed for E! News.

MacTavish said his drag persona, like much of the performance art at the time, was a response to the AIDS crisis that had taken so many of his friends. He performed once in a pageant called “Battle for the Tiara,” where he promoted needle exchanges, a harm reduction-based method of preventing HIV infection from used needles. Brooks said that at Club FUCK!, performance artist Ron Athey would do bloodletting on stage as a response to the anti-gay stigma during the epidemic. For MacTavish, tattoos and piercings also became a way of channeling the pain of the epidemic into something productive.

“The whole techno fetish club movement that we started kind of came from the repression of HIV and AIDS,” MacTavish said. “We would get notices that two people that you knew had died in the same week. And the memorial was on Sunday and you had to choose which person you knew better if you wanted to go to the memorial. And this is happening weekly. … The queer culture was coming up and filtering through all of the AIDS epidemic and finding ways to express ourselves and deal with the grief and the suffering and the loss.”