“There are some people who have more things in life and some people who have less things” says Matthew Troyer, who sponsors the Glassell Park community fridge.

Troyer works at L.A. ROAD Thrift Store on Eagle Rock Blvd. As a sponsor, he allows the community fridge to be placed in front of the store and plug into their power to keep the fridge and freezer running. He also helps to fill and clean the fridge when needed.

Like many involved in the growing community fridge movement, Troyer is motivated by the sense of rising inequality and the fact that many within his community struggle to find the food they need to survive.

Community fridges offer free food and water to anyone who wants them. All they have to do is show up and help themselves.

The community fridge program was started in Germany and reached the United States in 2019, but only really took off in response to the pandemic in 2020. It operates on the principle that communities can come together to create a system of mutual aid.

Today, there are around 200 across the country and an estimated 16 fridges in Los Angeles.

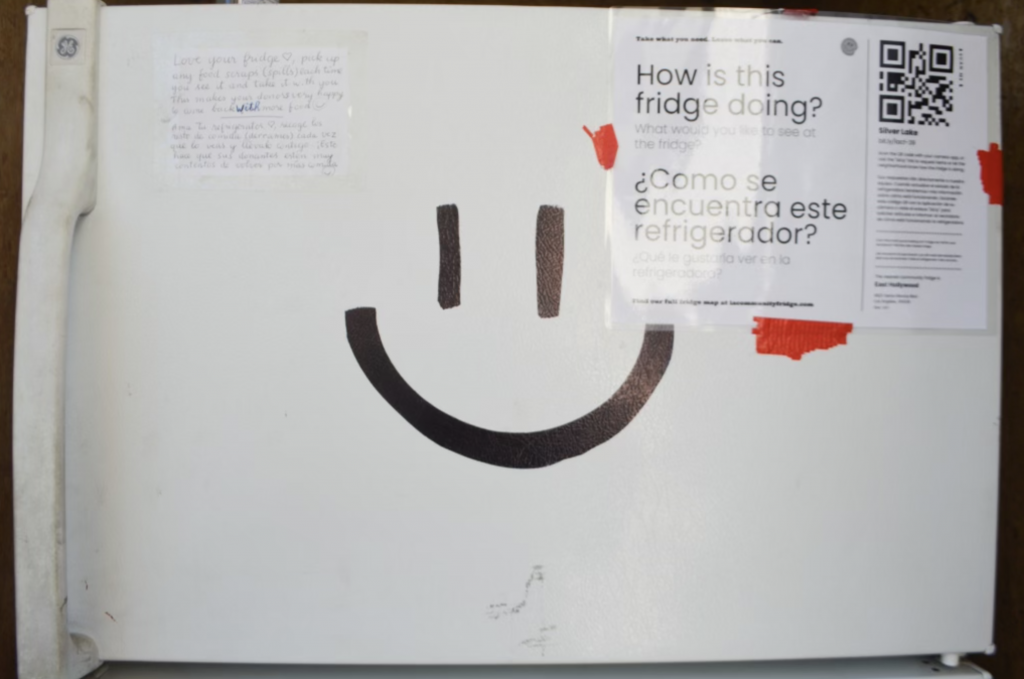

There is one tucked inside a laundromat on 1148 N Alvarado St in Echo Park. Others are on street corners. Many are brightly colored and decorated by local residents to make them stand out. Most have signs in English and Spanish announcing that they offer free food.

They bring together a wide range of volunteers and local business owners in what Gabrielle Datou calls an act of solidarity not charity

Datou runs a community fridge next to her cafe, Murmurs Café, on 1411 Newton St in the South Arts District of Los Angeles. It has been in operation since August 2020.

Datou oversees a refrigerator, freezer and pantry from which people can simply take whatever food they need. It particularly serves her street’s large community of people experiencing homelessness.

In summer, the fridge is kept stocked with bottled water, while the pantry offers canned and dry goods. The fridge’s focus is on staples such as milk, eggs and pasta, which can be used to make simple, nutritious meals. A local bakery brings leftover baguettes at the end of the day. EveryTable, a food service that’s mission is to “make fresh and delicious food accessible to everyone,” donates excess ready-made meals that volunteers can pick up, like a pesto pasta dish.

“Sometimes we fill the fridge at the café ourselves when it’s looking really sad, but we have an Instagram for the fridge where we’ll post things that we need and can gain tons of volunteers that way.” said Datou.

The community fridge program is as much about changing attitudes as providing people with food, she said. It is not a charitable program but a grassroots collaboration that looks to bring people together

The motto of the community fridge program is “Take what you need; leave what you can.”

Unlike a soup kitchen, “the nice thing about the fridge is that it’s not a set time every day and a specific day of the week. It’s always there,” said Missy Moulton-Church, a network wide volunteer.

It’s not about giving or even giving back. It is about changing out relationship to food and community.

Conrad Green, 49, has been using the Eagle Rock community fridge since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. He credits the fridge with supplying him with food that he would otherwise struggle to afford. It also has taught him to improve his diet and has had a positive impact on his overall health.

“It has made me a far more responsible person in terms of my diet.”

– Conrad Green

I know that with the community fridge you can not only be greatly assisted, but you can also go incredibly wrong and it forces you to make better decisions not only about what you eat but how you organize your day,” Green said.

He points to new foods that the fridge has introduced him to, such as mango gummies covered in rice paste to protect them from contact with their plastic wrapping and the interesting people he has met and exchanged advice with and shared information about particular products and new approaches to diet.

There is no way to tell exactly how many people use community fridges around Los Angeles, but estimates begin in the thousands. For many, like Green, the fridges have provided a lifeline in time of need.

It is estimated that one in five people in California currently suffer from food insecurity. This means that almost eight million people in the state suffer from occasional or constant struggles to access the food they need to maintain a healthy life. The pandemic, which has seen incomes dry up for people across the world, has only made the problem more urgent. In Los Angeles County alone, one million households faced food insecurity in the past three months.

Kelly Opdycke, 38, who runs the community fridge on Eagle Rock Boulevard, reports that her fridge is typically empty within a few days of being fully stocked. Anyone can take food from the fridges, and while there are no restrictions on what people can take, most people who use the fridges carefully choose their items according to their needs. All kinds of people use Opdycke’s fridge.

“There are a lot of unhoused people in the neighborhood who use the fridge. I’ve also seen moms and kids use the fridge. I’ve also seen people of all types donate to the fridge on a pretty regular basis,” Opdycke said.

Moulton-Church, 39, stresses that the need of community fridges differs based on the population they serve.

“If you’re going to South Hill or South Arts District where you see more of an unhoused population, usually things that are grab and go are best or foods that don’t require cooking. Anything that can just be taken and put in a backpack and eaten as is is really good,” she explained.

However, many users of the community fridges are housed and need food that they can take home and cook. There is also a need for water and for milk, which is especially important for families with children.

Moulton-Church, a longtime activist and organizer, believes that community fridges “provide easily accessible food in communities that have often not had easy access.” The other main purpose is to reduce food waste.

“Places like Trader Joe’s or bakeries where food is going to be disposed of even though it’s technically still good to eat, they just can’t resell it. It needs to be taken off the shelf based on its date,” Moulton-Church said. “Those things can come to the fridge instead of going to a landfill and can be enjoyed.”

The LA Community Fridge Network brings together fridges all over Los Angeles.

“We have a tech team that manages the website, we have communications and a social media team, we have people who manage fridge donations and transportation of fridges, people who build fridge shelters, we have artists who paint the shelters, we have translators,” said Moulton-Church.

“There are a thousand different ways that your skill set might be able to really help us.”

– Missy Moulton-Church

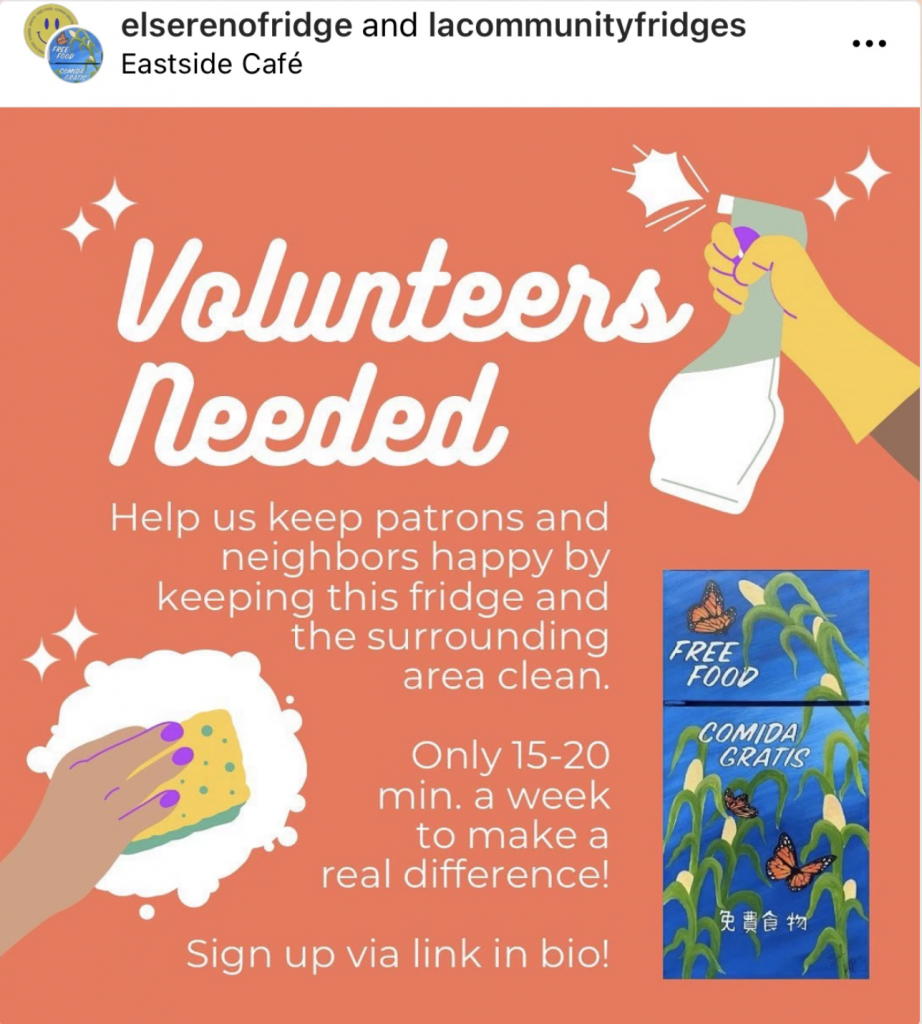

Typically, volunteers are recruited through a project’s Instagram account. However, lately, Datou and other organizers have seen some signs of fatigue and burnout.

“Last year it was easy to get volunteers. It’s been a little bit harder recently to get more volunteers,” Datou said.

Fewer coronavirus restrictions are also having an impact.

“Six months ago, we really started seeing it because people were required to go back to work. People’s priorities changed, people’s time availability changed, everyone got a lot busier. Including me. I had to reevaluate how much I could participate,” Moulton-Church said.

Moulton-Church believes it is important for volunteers to take breaks and not feel pressured into overextending themselves.

Opdycke believes that another way to combat burnout is to remind volunteers the way that the exchange is not simply one-way and how it connects to wider issues of social justice.

“The real way to avoid burnout is making sure that you know that you’re working with other people and taking on an issue. If you need to take a step back, you can vocalize it. There will be other people who will be able to step up for you,” Opdycke said.

“We aren’t used to asking for help or saying we need to take a step back, but I hope in mutual aid cultures we get better at asking other people to step up when we need them to step up.”

– Kelly Opdycke

The project is not without its critics. Neighbors adjoining Datou’s community refrigerator have petitioned to have it shut down and even called the police.

They see the project as attracting undesirable elements into the neighborhood and reflect what Datou calls the “pathologizing” of people experiencing homelessness.

Moulton-Church has experienced similar concerns from local residents.

She says, “I know that there’s a lot of people, like the nimby people who view this as something that will bring in more unhoused people into the neighborhood, which some people seem to be scared of. It’s usually a gentrifying business that perceives the fridge as drawing an undesirable crowd into their neighborhood. Which we usually view as it’s the gentrifying business that’s new to the neighborhood and that is pushing out this so-called undesirable community. In my opinion, they’re usually looking at it backwards.”

Sometimes, however, the residents win and succeed in closing a community fridge down. In the case of the Highland Park community fridge, local residents filed reports with the Department of Public Works Bureau of Street Services Investigation and Enforcement Division. The fridge received two citations and was eventually closed.

“Some fridges, like Highland Park, just weren’t possible. So unfortunately, that fridge was shut down because people didn’t like the visual of seeing hungry people outside nice restaurants, which again is like you’re looking at the problem wrong,” explained Moulton-Church.

The hungry Los Angelinos who help themselves to food at a community fridge give back by volunteering and by collecting food for others who cannot make it to the fridge themselves. It is not unusual to see one person collecting for several homebound individuals in his or her building.

For Datou, the project has brought her street together. The people who use the fridge, many of whom are currently unhoused, keep an eye out, preventing vandalism and excessive graffiti.

“They watch out for the block,” she said.

Opdycke says the movement will continue to grow if people who care about food inequalities in Los Angeles get involved.

“If there isn’t a fridge in your area, start a fridge in your area. Start them with people who are in your community. Start it and leave it with a good foundation. Use your creativity to think of other ways like the community fridge to help people who are food insecure. It took someone with bravery and creativity to get this started and now we have them all over LA. Use that creativity for good and see how you can help other people.”