When Owen Luebbers plopped down on the couch after a long day at an Irish dance competition in 2013, he opened up his iPhone and found his life – or at least dance career – had changed forever. A Vine of him performing original Irish dance choreography to “Am I Wrong?” by Nico and Vinz had blown up online.

As the video went viral on Vine and Twitter, Luebbers experienced a dopamine high he never had before – not even from winning international dance competitions.

“It was the craziest adrenaline, blood-pumping experience,” he said.

Almost 10 years later Luebbers is still chasing that high on TikTok, where he has over 250,000 followers. His videos have been shared by Fifth Harmony, Britney Spears and Ryan Seacrest. The attention is in part thanks to the cultlike Irish dance community, where the phenomenal champion dancer is, in a word, revered.

At age 5, Luebbers started dancing at the Campbell Academy in Philadelphia, before moving on to the Broesler School, where he remained for 12 years. Irish dancing runs in his family. His maternal great grandparents immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s from Donegal, Ireland. Luebbers’ mother took to Irish dancing to keep her family’s culture alive. Luebbers and his siblings, Ian and Cassidy, followed in her footsteps.

“I was basically dancing from the time I could walk,” said Luebbers.

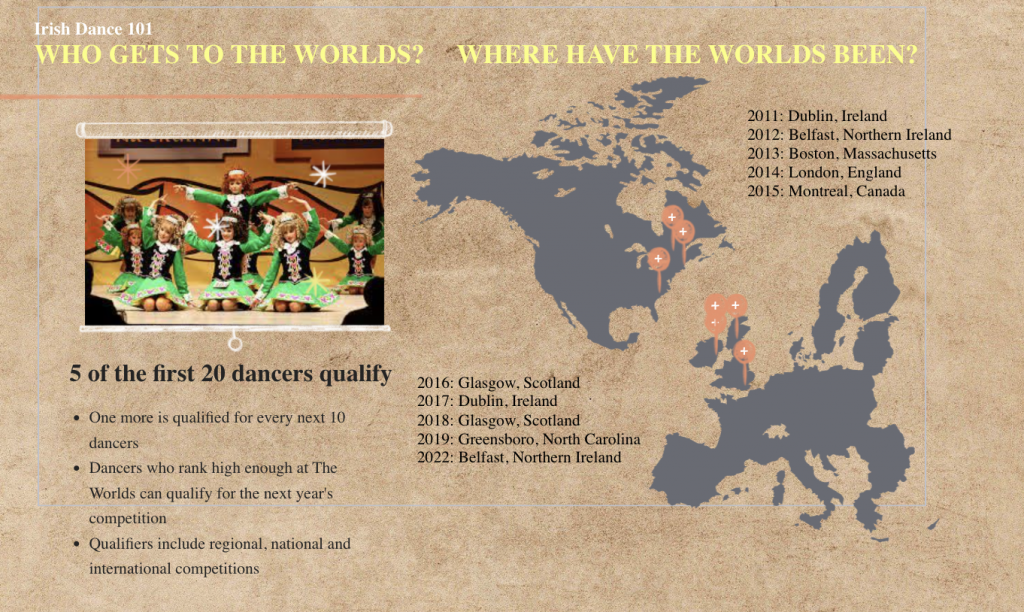

Since the 1970’s, Irish dancing has become a fiercely competitive culture. Dancers start as early as age 3, sometimes working over 20 hours a week to strengthen their craft. Competitions, or feisanna, take place regionally and internationally, culminating each spring with the World Championships. Few dancers will ever have the opportunity to grace the World’s stage.

Irish dancers compete not for cash prizes, but for reputation and acknowledgment that their dancing is the very best. Brand deals and careers with Riverdance, Lord of the Dance or other professional dance troupes come as a bonus, but it is the feeling of standing on top of the podium that drives most to sacrifice birthday parties and weekends to the sport.

Luebbers won his first regional championship, or Oireachtas, at 7 and has gone on to win every major Irish dancing competition, including the World Championships.

Before his first Mid-Atlantic Oireachtas — where he was a year younger than his competition — Luebbers told his family and teachers he was going to win.

“People would kind of laugh it off,” said Luebbers. “But then I did it. I think that [win] set a standard for the rest of my Irish dancing career.”

It also taught him to go into competitions with a winning mindset. Over Thanksgiving weekend 2021, Luebbers won his 13th regional title. Luebbers has only lost the regionals once. He also won the World Championships in 2017.

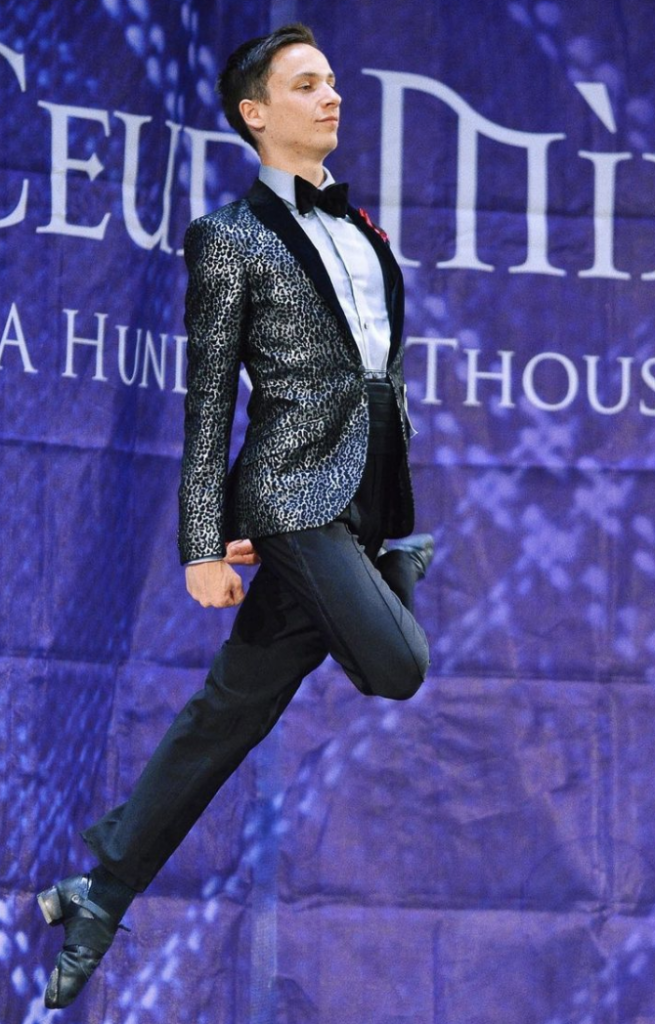

(Photo courtesy of Luebbers)

His competitive success aside, Luebbers has also become iconic in the closeknit community of dance fans due to social media. He was one of the first Irish dancers to begin posting videos of dancing, not just to Irish tunes, but also to pop songs like “Neighbors,” by J. Cole. These videos can inspire dancers to add new tricks and help styles evolve and stay fresh. But they can also influence results at competitions, as teachers – who oftentimes serve as adjudicators at major competitions – notice rising dancers.

“There’s a lot of corruption that takes away from the beauty of Irish dancing,” Luebbers said adding, “The people who are trying to build a presence for themselves tend to be the people who are doing better at competitions.”

Like figure skating and gymnastics, Irish dance is scored on a subjective basis. Competitors often see a variance in their results, and it can sometimes stem from who is dancing that day and who is sitting at the judge’s table. A dancer’s scores can be influenced by everything from toe height, to skirt length, to their dance school’s name.

Luebbers also feels misunderstood by a lot of fans who pay little attention to his personality outside of dance.

“Social media is a dopamine factory. I would post pictures of me at a school dance or whatever, and they would get less likes. It would be like, ‘Oh, so I guess people don’t care about this version of me,’” said Luebbers.

Many of his fans even took a sarcastic Instagram post from July 2021 seriously. It was a photo of Luebbers in a vest with a friend wearing a white dress. The caption read, “I got married today!!!! My beautiful wife and I had a quiet ceremony followed by a reception surrounded by family and friends!!! Here’s to forever.” Despite its cheeky tone, he received countless well wishes from earnest fans. He believes this misunderstanding stemmed from the lack of engagement with posts about his rich life outside of dance and competition.

“That post is the kind of joke I would make,” said Luebbers. “There’s just like so many context clues that, like, anybody I feel could pick up on — but just didn’t.”

Another Irish dance world champion and one of Luebbers’ closest friends, Julia O’Rourke, has a different problem. She rose to dance fame in 2011 with the release of Sue Bourne’s “Jig.” It was the first feature-length documentary about the sport. Julia’s road to her first World Championship win was intimately documented, propelling her to become an Irish dance icon and role model.

“I seriously love all the messages that I receive,” said O’Rourke. But, she added, “On [competition] days, I really wanted to focus on myself… It was overwhelming with hundreds of little dancers coming up to me and taking pictures of me.”

She has also found that idolization comes with hate — something that was especially hard to deal with as nearly her entire dance career has been recorded and judged on social media. O’Rourke made an Instagram at 13 — two years after “Jig” — and gained thousands of followers in a matter of months.

“It was all a shock to me… I had to mature really quickly on social media, because you want to be personable with people,” said O’Rourke. “But at the same time, it becomes a personal hazard if you post too much about yourself.”

In between glowing comments, Instagrammers were not afraid to share their opinions about everything from O’Rourke’s pre-teen outfits to her placements at the World Championships. Others made hate accounts. She said her mother had to help her deal with the stress by encouraging her to delete harmful messages and remember haters are just hiding behind a screen.

“Everyone knew who I was and kept an eye on me,” said O’Rourke.

(Photo Courtesy of Luebbers)

In the past few years, the Irish dance universe has been especially fixated on Luebbers, who has endured personal adversity throughout his career. It began with his primary teacher, and the founder of the school where he trained for 12 years, Kevin Broesler.

“There was an aspect of duality to him as a teacher and as a dad or family guy,” said Luebbers, adding “Then there was a third side that not a lot of people knew about, and I didn’t know about until I was at the point where I was going to leave the school.”

In December 2019, at least two lawsuits alleging Broesler sexually abused minors were filed in New Jersey’s Bergen County Superior Court. The alleged instances occurred at dance competitions between Broesler and dancers who were not his students.

A week later, Broesler penned an open letter to the Irish dance community in which he denied the allegations and suspended himself as an instructor.

Luebbers had already left Broesler’s school – before the lawsuits– in the spring of 2018. He was following his brother, Ian, who in the fall of 2017 had transferred to the Holly and Kavanaugh School in Dublin. Luebbers says he was never assaulted by Broesler. But he did cite a problematic power dynamic between the two, including multiple instances where the Luebbers family was threatened with expulsion from the dance school.

These occasions were especially difficult, because Luebbers was homeschooled. His entire social world existed within Irish dance and, he said, what he describes as Broesler’s toxicity consumed him. It wasn’t made any easier by the tens of thousands of dance fans who weren’t afraid to voice their opinions about Luebbers’ transfer and the purported legitimacy of the lawsuits against Broesler.

This only worsened in June 2019, when his older brother —and fellow world champion— Ian died by an apparent suicide.

“In the first couple of days, we knew that we were going to have to say something,” Luebbers said.

But it was already too late. Posts about the death circulated on VoyForums, an Irish dance message board, before the Luebbers family announced the death.

“One post alluded that [Ian] killed himself because he didn’t win The Worlds, which is just so insensitive and messed up,” lamented Luebbers.

The speculation continued. At an Irish festival in Maryland, Luebbers dedicated a performance to his late brother. When he got off stage, an unfamiliar dance mom pressed for information about the death of Ian, likely out of a sense of “morbid curiosity,” said Luebbers.

This period made Luebbers want to quit dance. He struggled during his return to training in Dublin.

“[Ireland’s] where we bonded as brothers and as friends,” Luebbers said, “Sometimes it’s painful, but then there are some times where it’s euphoric… [I’m] trying to figure out how to balance those.”

The pressure of being constantly in the public eye via social media made it all the more agonizing to process the death of his beloved brother.

(Photo courtesy of Luebbers)

Still, he said, “I see dancing as this gift that I was given. The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve come to understand what it means to have a gift and what it means to share that.”

His current teacher, Niall Holly, is a world champion dancer, former Lord of the Dance lead, and Irish dance adjudicator. He applauds Luebbers’ focus and resilience when training.

“Dancing has been a savior for Owen in many different respects,” said Holly, adding “He’s somebody who knows how to channel dancing in the right direction for achieving that sense of elevation from the outside world.”

His resilience shines not only for his teachers and friends, but to anyone lucky enough to watch him.

(Photo courtesy of Luebbers)

“Every time he walks on stage you can see the love and joy in his performance,” said his sister, Cassidy Luebbers. “No matter what happens he commits and goes for it.”

She’s talking about his most recent win over Thanksgiving weekend at the Mid-Atlantic regional championships. During Luebbers’ final performance, his music – which is always played by a live musician – was much too fast. He made it work well enough to secure his 13th regional title.

O’Rourke, his close friend, has also been one of Luebbers’ biggest fans for the last 15 years.

“You can see the amount of hours he practices and how much he loves it [on stage]… Everyone roots for him,” she said, “because he works so hard.”

In the run up to the 2022 World Championships – the first one in three years – Luebbers will be training hard and, as always, documenting his life and creativity on Instagram and TikTok.

“I just think I owe it to my brother to have the experience that he had of living in Ireland and dancing… I think it’s something,” he said, “that I just need to do.”