“The only reason I came to know what calories are and why people track them is because of TikTok. And I did track my calories for a really long time during quarantine, which was horrible for me. It’s a terrible habit for anyone, especially for a teenage girl like myself,” — Ava M. — a 17-year-old high student from Santa Monica, CA.

Ava and her two friends, Riya and Dominique, downloaded TikTok at the start of quarantine. Their last names will be kept anonymous, out of respect for them and this sensitive subject matter. Like so many of their peers, they were looking for a distraction from the rigor of their school work and the monotony of the COVID-19 lockdown, through short, funny videos of the latest dance moves or other new trends.

“I think that it’s a fun space for some people to relieve stress or just dance and make funny videos,” Riya said.

But for many young women, TikTok has proved to be a tricky platform — posing inescapable challenges to their mental health. It’s not solely dancing videos and lighthearted entertainment — it can be fad diets, intermittent fasting, calorie counting, detailed food diaries, and weight loss transformations.

“Most girls who come up on my ‘for you page’ are really really skinny and look like the beauty standard. I sometimes wonder why I don’t see people with other body types on my feed. It feels harmful that people so casually look good and honestly, after quarantine, all of my friends were affected in some way,” said Ava.

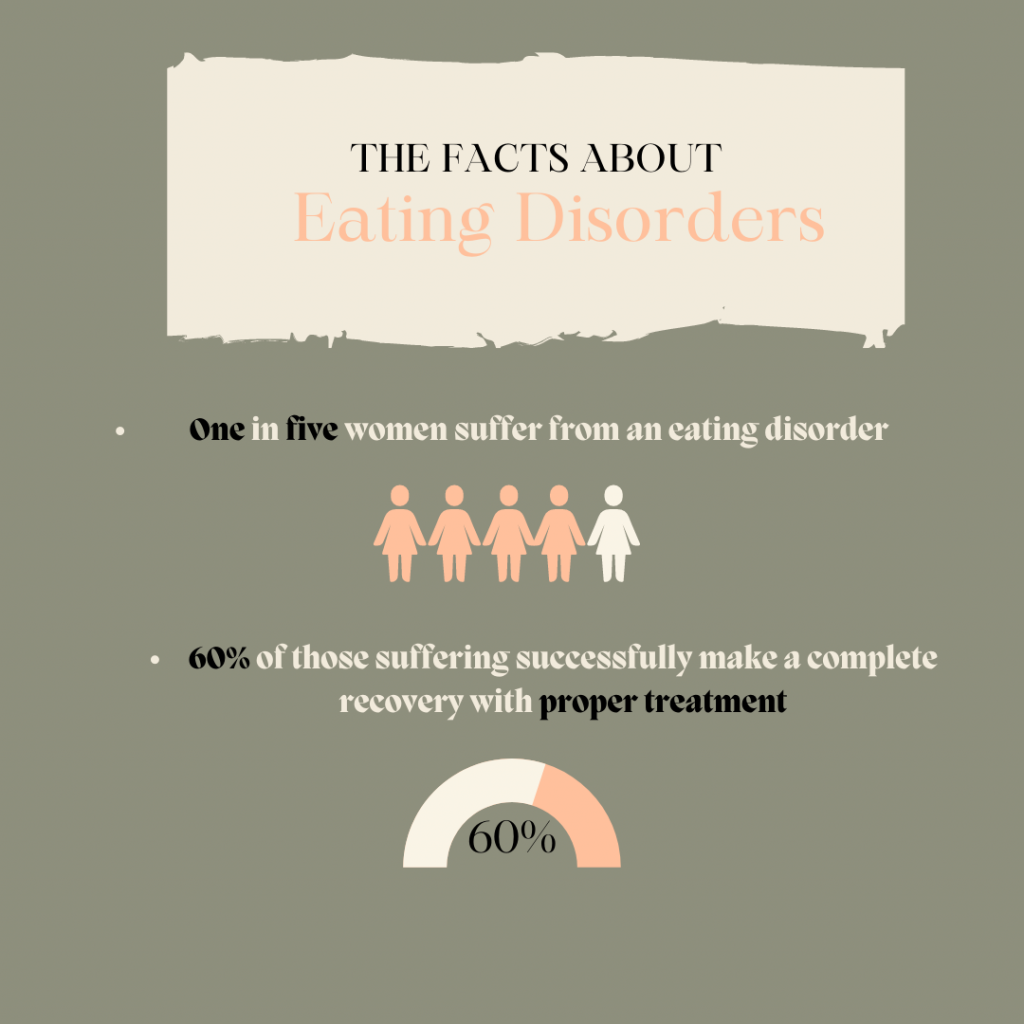

Dr. Barbara Cadow, a long-time specialist in depression, anxiety, food-related issues and eating disorders, said her Los Angeles based clientele is getting younger and younger with each passing year. Recently, Cadow has been treating more young women ages 14 to 15 years old. The majority of her clients are on social media and nearly all of them are on TikTok. To Dr. Cadow, the constant comparison of TikTok is the most concerning aspect for her clients.

“It’s obsessive, compulsive, perfectionistic..and totally out of the realm of reality,” — Dr. Cadow, psychologist, Los Angeles, CA.

Cadow saw that many of her patients turned to TikTok during quarantine, partly because of boredom and a need to distract themselves. Many of her patient’s eating disorders worsened over quarantine, which she attributed to increased anxiety and confinement. With the isolation that COVID-19 inflicted for many, it’s no surprise that eating disorder rates blossomed in the last year and a half. Unfortunately, TikTok flourished, too.

Now that COVID-19 restrictions have loosened, Cadow worries that her clients will struggle to reacclimate to in-person life after nearly two years online. She said the term “FOMO” or the “fear of missing out” is a very real anxiety for young women. With the constant need to post online, TikTok has made this problem even worse, she said.

“It makes everything so glorified. I know it’s only what people choose to film, but it made me think that’s what my entire life should look like. I feel bad, sitting at home, thinking about what I should be doing,” — Dominique K., a 16 year-year-old high school student, Pacific Palisades, CA.

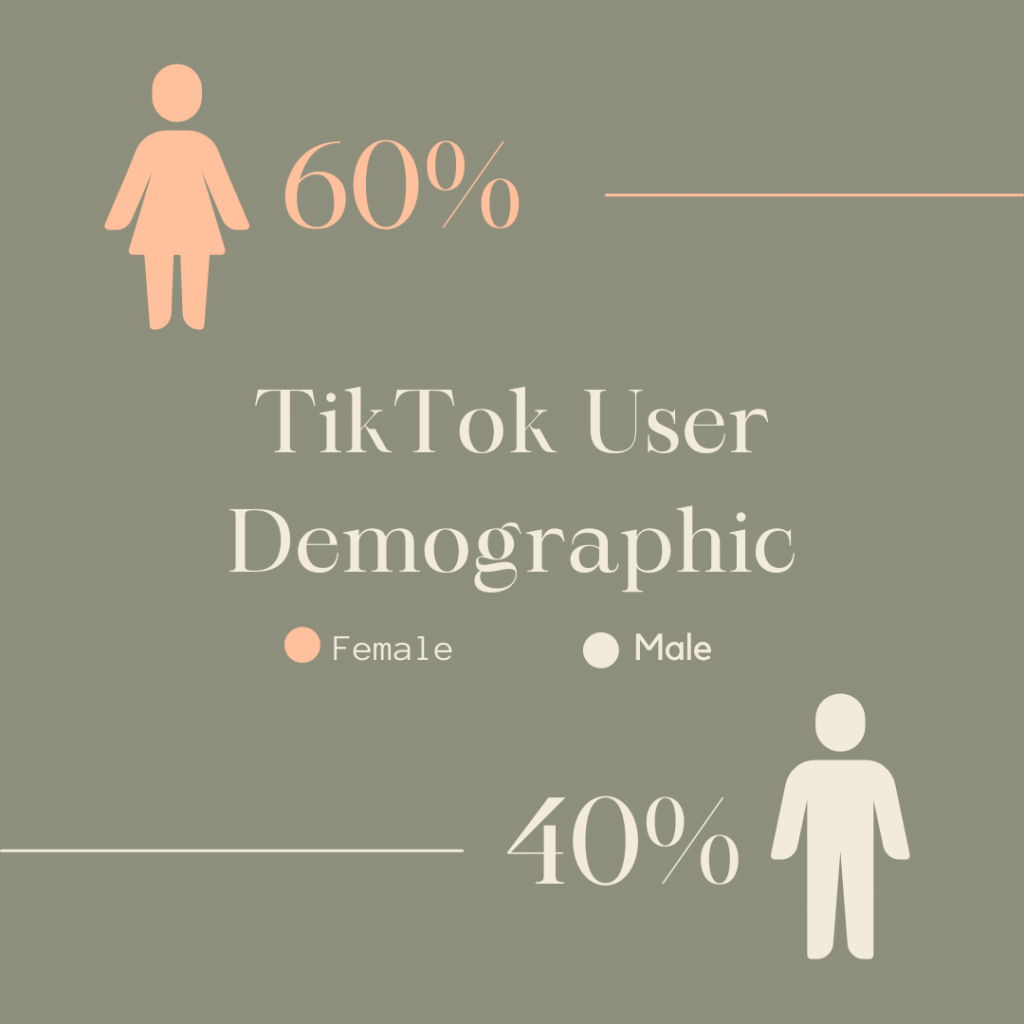

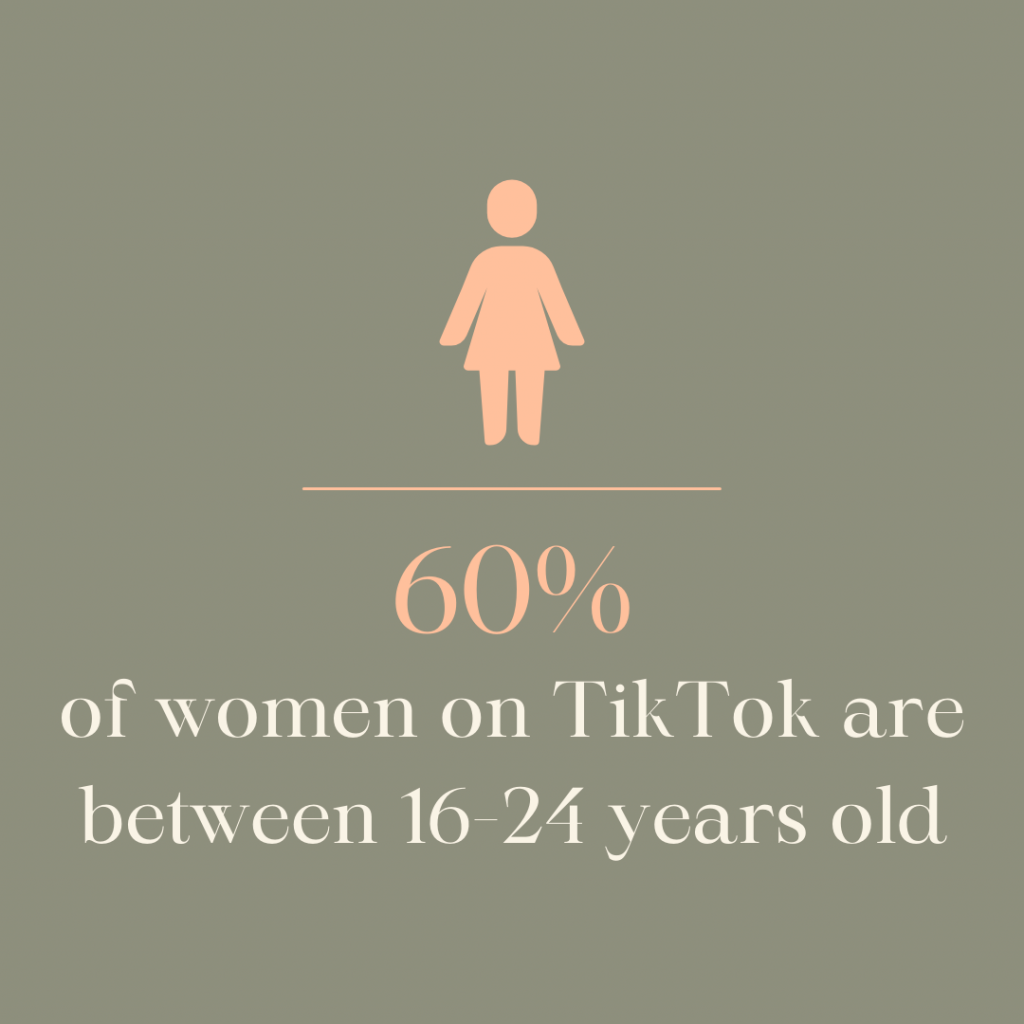

TikTok has nearly 1.2 billion active users globally and over 800 million monthly users. In the United States alone, TikTok has roughly 80 million monthly active users. More than half of those are female — and 60% of those women are between the ages of 16 to 24 years old. TikTok’s minimum age requirement is 13-years-old, but one of TikTok’s former employees who recently left the company told the New York Times that the app does very little to restrict or remove videos from underage users. According to the Times, the company’s internal documents show there are roughly 18 million TikTok users in the U.S. alone that are 14-years-old or younger. TikTok has continued to defend their position, remarking that they are constantly implementing new ways to monitor the app’s age restrictions. The former TikTok employee told the Times this is not true.

Bottom line: one of the world’s most widely circulated apps in history is used by a great majority of young people — and young women, including very young women.

“All of my friends have TikTok, I don’t know anyone who doesn’t,” said Ava.

Middle schoolers, young women between the ages of 12 to 14-years-old, are grappling with their bodies changing, friend groups shifting, and academic life becoming progressively more difficult. The culmination of these adjustments often leads to feelings of rejection, despair, depression, and anxiety that can linger on into early high school years, said Cadow.

“When I see a high school student that comes in that is depressed and or anxious, I ask them when it started. And they all say the same thing. Middle school,” she said.

There are 15.3 million students enrolled in grades 9 through 12 and roughly 4 million 7th graders and 4 million 8th graders in the United States. With nearly 18 million users in the United States under the age of 14-years-old, it is clear that the majority of American middle schoolers are on TikTok.

“They are adapting to their bodies…maybe they have acne… and they look online and they see perfect people.. it shapes women to feel like they’re less than, they’re ugly, they’re not good enough. This is when disordered eating can start,” said Cadow.

Roughly 30 million Americans have or have suffered from an eating disorder. Over their lifetime, about 0.9% of American women will develop anorexia nervosa, 1.5% of women will develop bulimia nervosa, and 3.5% of women will develop binge eating disorder. Eating disorders are not limited to these three diagnoses or just women in general — but the association of disorder eating to women is strong.

Laeti Decaru, a body positivity influencer with a TikTok following of 763 thousand users, began her career online after dealing with an eating disorder for nearly 15 years of her own life. Decaru’s goal with her platform is to create content that she would have needed as a young girl — posting candid documents of her self-confidence journey and raw footage of her mental health battles.

“I do believe TikTok can start eating disorders because it’s so accessible. You scroll all day. Parents have no control over that. It can be so easy to compare yourself, ” said Decaru.

TikTok, unlike any other photo or content sharing app, is video-based. Creators and users can generate up to a three minute video of themselves featuring almost any type of content — food, exercise, dancing, art, home decor, sports, social commentary and comedy. In terms of mental health and women, there is a heavy “eating disorder recovery” community on the app, as well as a staunch “body positivity” community, a “keto” community, an “intermittent fasting” community, an “intuitive eating” community and the list goes on. The problem with these various communities — with every view, like, or share, your algorithm learns what catches your eye. An individual can view one Tik Tok with a seemingly positive message and consecutively scroll past another with a negative message. The result: a confusing environment for young women that leads them to ask the question — what should I really look like? Am I good enough? Where do I belong?

Female creators like Decaru aim to change the narrative surrounding lifestyle videos by videoing and photographing authentic accounts of real life — the highs and the lows.

“People have lifestyle videos, where they show what they eat in a day or how they exercise. A lot of times, those videos are just to show how skinny they are. And they’re basically saying, ‘if you eat like me, you’ll look like this.’ It sends a really negative message,” said Ava.

For Ava, the video based aspect of TikTok is specifically challenging for her and her friends.

“Videos are more real life than a photo. When you’re looking at a photo, everyone can think you’re posing or sucking in. If you look at a video, you think it’s really raw and the perfect representation of how someone’s life is,” said Ava.

Ava said that her relationship with TikTok can be confusing and difficult. One day, her algorithm can be purely positive — showing videos of recipes, exercise, or fashion. Next, her algorithm will highlight more intense accounts of weight loss or dieting.

“I can’t think of one girl I know that’s really confident in their body and themselves,” — Ava M. — a 17-year-old high student from Santa Monica, CA.

TikTok’s algorithm has an inherent dark side. As soon as you download the app and enter your information, TikTok starts compiling personal data about you — your location, gender, age, and even your facial data. At the beginning, your algorithm will feel impersonal and random. But with the more videos you “like” or accounts you follow, TikTok becomes knowledgeable about who you are.

Dr. Kalinda Ukanwa, a professor of marketing at the University of Southern California in the Marshall School of Business, studies algorithms and algorithmic bias. Dr. Ukanwa said that algorithms are purely a list of instructions. They learn from previous data or past behavior. Their goal is to have as many people view content as possible. Based on the patterns that the algorithm learns, or what a certain group of people tends to click on or “like,” the algorithm will circulate more of that similar content to you.

“When you see pro-anorexia content being fed to girls that are too young to even contextualize it’s dangerous and harmful. The root cause of that… is because at some point early on in the system, there were girls of that age clicking on that content. Then it starts to learn and generalize to other girls, who have no interest in that content..this group seems to like this,” said Dr. Ukanwa.

Dr. Ukanwa makes it clear that this is not the fault of young women. She said there needs to be a higher level of responsibility than just simply having an algorithm learn from past data and letting it run wild without having checkpoints of morality, fairness, and bias.

Decaru said that her videos that emphasize her stretch marks, acne, and cellulite often get banned by the app. She feels frustrated that the unflattering traits of her body can be censored, while more thin creators who fit the beauty standard often post revealing videos in bathing suits and workout gear, said Decaru.

“Fairness and change means holding TikTok accountable for protecting creators with more followers than me, or who look a certain way that fits the beauty standard,” said Decaru.

For women and girls, the intelligence of the TikTok algorithm can be specifically problematic. It is common that most women will initially see a type of fitness content. Whether it is workout ideas, healthy recipes, or even other women attempting to lose weight — because women in the past have interacted with this content. These videos can set an unhealthy trap. Once the algorithm senses a remote interest in this genre of content, videos can quickly alter to showcasing severe amounts of under eating.

The hashtag “#whatIeatinaday” has nearly 9 billion views. These videos commonly highlight detailed food diaries of what various people eat throughout the day. They can be harmless and normal. More commonly, they are triggering and unhealthy. Experts highlight that not only can “what I eat in a day” videos be a toxic trigger for those with mental illness or a past history of disordered eating, but they can provoke unusual eating habits for people with no prior history of an illness. They are frequently combined with “body checking,” a compulsive check-and-check again behavior loop where an individual scans themselves for any apparent physical changes. The combination of toxic “what I eat in a day” videos with body checking can be a catastrophic mix.

“When quarantine started, I went on TikTok a lot. Looking at people’s ‘what I eat in a day’ videos really started to get to me. It just makes you feel bad” said Dominique.

Dr. Jamie Sidani, an assistant professor of medicine at The University of Pittsburgh, said that the social comparison of “what I eat in a day” videos can be the largest trigger for young women. In a 2016 study conducted by Dr. Sidani, it was found that both Youtube and Facebook had a high amount of “pro-anorexia” content. Dr. Sidani describes “pro-anorexia” content as when individuals with eating concerns seek out each other online. Those who encounter one another may make pro-eating disorder groups, where they discuss loneliness, ways to undereat, tactics to manipulate weigh-ins, and photos of other thin women. Because TikTok does not have the “group” feature such as Facebook does, “pro-anorexia” content can materialize more subtly in the form of restrictive “what I eat in a day” videos or severe body checking. Similarly to Dr. Ukanwa, Dr. Sidani argues that the app needs a higher level of responsibility. Until then, it is the job of parents to teach their children how to interact with harmful content.

“I’m a big proponent of media literacy, which teaches young people how to critically analyze the media messages they’re coming into contact with…Understanding how these things work so that you can take a step back and see if it’s in your best interest or not,” said Dr. Sidani.

Hope Virgo, a woman who struggled with anorexia nervosa for the majority of her teen years, is an online advocate for a similar kind of media literacy — destigmatizing eating disorders. Virgo said that a large problem with TikTok is that many women will seek both self-worth and weight loss advice on the app. Because eating disorders are known to be competitive, it is dangerous for young women who are struggling to constantly see detailed accounts of other people’s weight or what they eat.

“Eating disorders are really competitive illnesses. The eating disorder will often tell you that you’re not sick enough, you’re not deserving of support.. all of these videos definitely fuel that competition because you end up looking at what someone else is doing and judging yourself,” said Virgo.

Virgo said that our brains are powerful enough to distort the reality of the videos we watch. Oftentimes, we believe that everything we see is raw, unedited, and unfiltered. Women commonly accept that because TikTok is solely a video based app, individuals cannot edit their videos — it’s impossible to retouch a blemish or physically alter the dimensions of your body. This unfortunate presumption is false. Various body image experts have attempted to make this known to the app’s users. Victoria Garrick, a former University of Southern California D1 volleyball player who has now dedicated her career to advocating for mental health and body acceptance, posted a video to her TikTok account with 1.1 million followers showing how it’s not only possible to edit a video, but edited videos can appear untouched and realistic. Garrick posted a video of herself in a bathing suit. She edited one clip to make her waist smaller and features thinner. She left the original clip untouched, mirroring them side-by-side to show how severe and realistic editing can be. Garrick’s video got nearly 9 million views and shares. She wants everyone to know those TikTok videos can be edited, just like photos on other platforms.

Sloane Elizabeth, a New York City based holistic wellness coach with nearly 20 thousand followers, deleted TikTok herself due to her own frustrations. Elizabeth believes in helping women eat with love and intuition. She uses both science and spirituality to encourage women to make space for anti diet culture rhetoric, release obsession and food rules, as well as find peace from food restriction and binging. Elizabeth said that unfortunately, women comparing themselves to one another is a difficult problem to overcome. Constant comparison can lead to or worsen depression and anxiety.

“Comparison can also re-work the neural networks of your brain, making comparison a severe habit that becomes easier over time,” — Sloan Elizabeth, Holistic Wellness Coach, New York, NY.

For Ava, Riya, and Dominique, the future of their mental health is dependent on how TikTok’s guidelines progress over time. Big Tech platforms such as Facebook and Instagram are facing scrutiny in Congress, in part regarding the safety of young, female users, it is possible that TikTok’s rules and regulations become stricter on the circulation of knowingly harmful content. Even though TikTok is Chinese owned, Ava, Riya, and Dominique hope that the recent pressure on American social media apps will cause TikTok to make changes.

“I hope as people get more and more aware of the negative effects, those pages and comments that are harmful will be taken down,” said Ava.

TikTok has taken precautions to stop the spread of pro-eating disorder content, such as banning the hashtags #proana or #anorexia, which had nearly 2.1 million views this past summer — an accurate account of just how catastrophic content can be. Users who searched for these hashtags were then directed to a support page with the headline “Need Help?” Preventative measures such as this one can be useful, but recent reports suggest that toxic hashtags are being purposely misspelled, making this content difficult to restrict.

“Until change happens, we can try and look at diverse content. Look at content that is helpful…take ownership of the content you’re consuming…Have some mantras at hand, such as ‘you are so much more than your body,’” said Virgo.

Virgo, and other female creators like Decaru and Elizabeth, said that trying to focus on what you can do for yourself, rather than what the app can do for you is our best bet in solving this problem until change occurs. This requires shamelessly blocking people that toil with your self worth or make you feel inadequate. The power of our phones is that we are one click or dislike away from reshaping our peace of mind. Consume content that makes you feel powerful and strong. Be in charge of what you see, even if it’s hard, said Virgo.