It’s 2021. Lockdown has somewhat ended, but grey skies and heat waves remain.

When lockdown hit in March of 2020, virtually no cars shuttled to and from work. Many experts expected that the historically smoggy city of Los Angeles would see air quality improvement — which did happen… for about 20 days. However, the year of 2020 ended frightfully with 157 total “bad days” for ozone pollution — the worst air quality has been since 1997, according to Coast Air Quality Management District, a branch of the California Air Resources board.

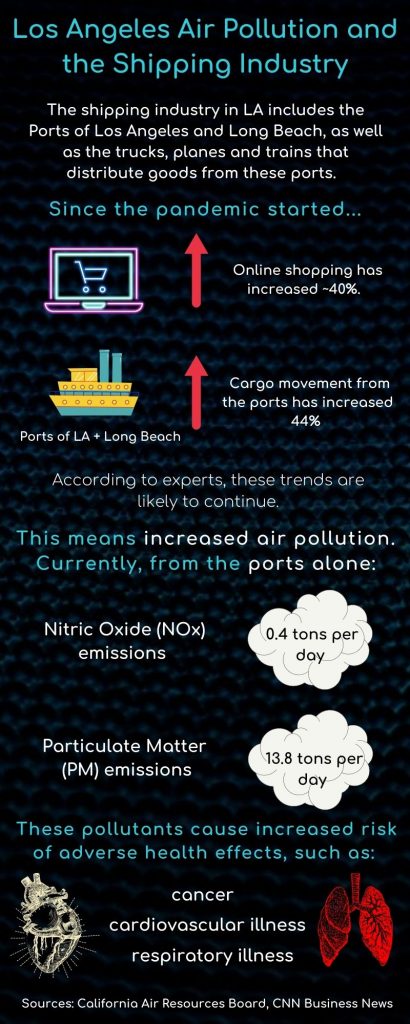

“What happened was, even when folks continued to work from home, the trucking industry went on. They still had to go to the port to pick up goods. People are still buying stuff online,” said Raj Dhillon, the Senior Manager of Advocacy for Breath Southern California, which is a nonprofit organization that promotes improving air quality and health. In fact, online shopping has increased nearly 40 percent since the start of the Pandemic, according to a CNN business article interviewing the Google’s president of commerce.

As we approach the holiday season, Angelinos’ air quality could be a concern. The city of Los Angeles is centered around one of the Western Hemisphere’s largest shipping industries and a major air polluter. The shipping industry here refers to the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, along with the trucks, planes and trains that distribute goods brought from the ports — basically, all the moving parts that bring that new sweater to your doorstep. While the shipping industry is not entirely to blame for air quality in Los Angeles and the rest of southern California, it was to blame for nearly half of it as of 2019, according to the California Air Resources Board. This number is likely much higher now, considering that the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach have seen a 44 percent increase in cargo movement compared to since 2019.

Will Angelinos see the air quality effects of holiday season shipping immediately? Perhaps not. In general, though, the trend of shipping and shopping sees no sign of stopping.

“Our Port Optimizer data indicates significant volume headed our way throughout this year and into 2022,” Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka said in a statement.

The problem with increased shipping activity is the resulting increase in health-damaging emissions spewed into the air. Specifically, this means Angelinos breath in high levels of particulate matter (PM) emissions and smog-forming oxides of nitrogen (NOx), the major harmful emissions. Exposure to PM and NOx can have severe health effects, including increased risk of cardiovascular events like heart attacks, or respiratory issues like asthma or bronchitis. For those with pre-existing respiratory issues, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), even small increases in PM and NOx emission can cause conditions to worsen dramatically, according to Raj Dhillon.

The difference in air quality between Los Angeles and cities located further from the shipping system is striking. Joe Saltzman, an 82-year-old professor at University of Southern California (USC), says he had zero breathing issues during 2020. He attributes this to being able to teach class online from the comfort of his home in Palos Verdes, which is further from the shipping industry. Now that USC classes are taught in-person, he must commute to downtown Los Angeles every day and has noticed significant smog-induced breathing issues and allergies.

“Every time I drive into LA and spend a whole day here, when I go home, I will have problems breathing tonight or tomorrow morning because I spent all day in LA,” Saltzman said. “There’s no question, I can feel it immediately.”

Minority and low-income groups get hid the hardest, by far. These groups tend to live in neighborhoods along the goods movement path. That is, minorities tend to live closest in proximity to polluting areas like highways or ports. In addition to historically dealing with higher levels of pollution, Dhillon said minority communities experienced the biggest health impacts due to reduced air quality, which overlapped with resulting susceptibility to COVID-19.

“When you look at coronavirus and the COVID-19 pandemic, it was those disadvantaged communities that were hit the hardest,” said Dhillon. “Those were a lot of the frontline workers and individuals that do not have the resources that other communities have, such as proper air conditioning or the means to socially distance. So, you see a lot of overlap between the pandemic and the pre-existing high-pollution that burdens these communities.”

In addition to not having amenities like proper air conditioning, many low-income and minority communities also lack natural resources like access to parks and green space. A lack of these resources, which act as a natural buffer to pollution, causes them to be more succepstible to bad air quality, according to Monalisa Chatterjee, an assistant professor of teaching for the Environmental Studies Program at USC.

“Los Angeles is a critical area from an environmental perspective because when you don’t have green space, you don’t have that air purification process happening which trees can provide,” Chatterjee said. “The concentrate absorbs more heat, and creates what is known as a heat island, and the pollutants are more concentrated in these areas.”

The issue illustrated here falls within the concept of environmental racism. Historically, minority groups feel disproportionate effects of climate change — in any city — because these neighborhoods are normally located in high-polluting areas. But in Los Angeles, Chatterjee said the problem is amplified because of the affordable housing shortage. That is, even when efforts are put in to transform a high-pollution area into a more livable one — by adding trees, clearing toxic waste, or other methods — rarely do minority and low-income communities see those benefits.

“In places that go through the transformation, most of the time, the marginalized communities get pushed out because the value of the land goes high and richer people move in as soon as the quality improves,” Chatterjee said. “These original populations then get pushed into even worse conditions [by having to move to even worse-off neighborhoods].”

Chatterjee said that one way to ease this situation is by advocating for financial policies to help minority communities get housing loans so they can afford to continue living in a neighborhood once it’s been cleaned up, instead of being pushed out.

“It’s not only about making something affordable, but also about facilitating the capability of marginalized communities to actually go through the process of getting a loan and buying it,” said Chatterjee. “Historically, we have seen that that has played a very significant role.”

In order for any environmental or equity changes to take place, citizen education is necessary. Some experts said that greater reliance on the internet and social media during the pandemic has aided the average Angelino’s knowledge about climate change. Others disagreed or said it is not enough.

Elizabeth Rhodes, the Director for the LA County Department of Public Health Climate Change and Sustainability Program, said switching to using the Zoom platform to host previously in-person environmental meetings has increased community attendance. These meetings often include information about how to access community resources, for instance, where to find cooling centers during a heat wave. On the other hand, Rhodes said that social media has fostered a more polarized political climate, with more vocalizatoin from groups that deny climate change, impeding support for government efforts that reduce climate change.

“You know, really, our sole goal is to try to keep people alive and healthy. That is the motivation from which all our decisions are being made,” Rhodes said. “It’s really disheartening to realize that some people just don’t seem to understand that.”

Rhodes said that one approach to get people to care about air pollution and climate change is to appeal to health concerns. She said this is an “accessible and non-threatening way” to open peoples’ ears and lessen political lash back.

In this case of getting people to care about pollution from the shipping industry, appealing to health concerns might mean explaining the health-damaging nature of nitrous oxides and particulate matter.

On a different note, Dhillon said he does think Angelinos have more knowledge about climate change, however, their education is too general. That is, the media often focus on a national lens, not a local lens. Learning about environmental issues that specifically plague Los Angeles, or even a particular region of Los Angeles, is the key to making beneficial change.

“I’m not totally convinced that the typical Angeleno is aware of some of the driving forces behind climate change and what policies need to be addressed to meaningfully address the issue [at a local level],” Dhillon said.

Perhaps with more specialized environmental education by entities like the LA County Department of Public Health, and more citizen advocacy, solutions can be found to cure the air pollution plague that had infected Los Angeles.