California is the only place in the United States where fishing drift gillnets are still used legally. Gillnets have already been banned in other territorial waters in the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, and off the west coasts of other states such as Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and Hawaii.

“Drift gillnet fishing is a really indiscriminate form of fishing,” says Shark Stewards director David McGuire. “ It doesn’t truly target catch well, at least 66% bycatch meaning…things that are caught accidentally that end up dead or dying or sometimes alive and thrown over the side while the directed capture is maintained onboard.”

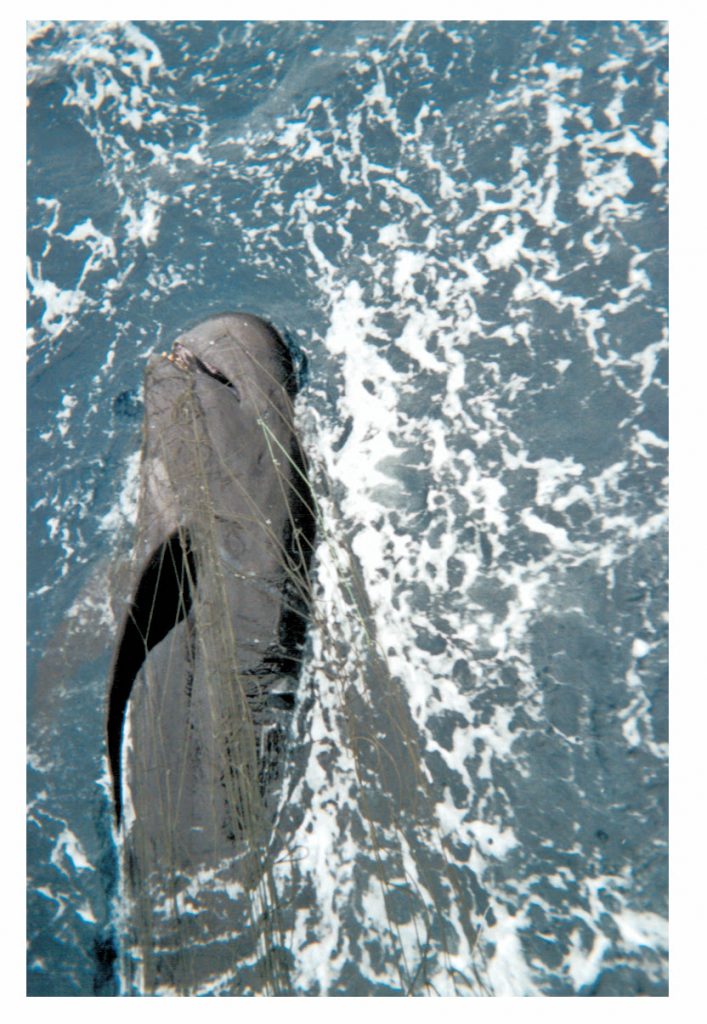

The use of large drift gillnets as a fishing practice has been proven to be detrimental to a vast array of marine life, indiscriminately capturing seabirds, turtles, sea lions, swordfish, sharks, dolphins, and whales. Drift gillnets harm marine ecosystems in a multitude of ways consisting of bycatch, derelict fishing gear pollution and ghost fishing.

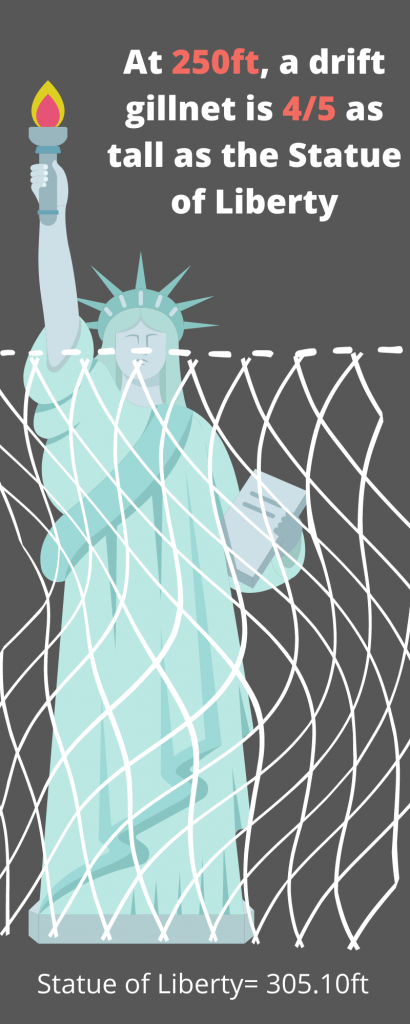

Constructed to ensnare swordfish and various shark species, drift gillnets are made of monofilament, or multifilament, nylon netting with a mile-long width and a depth of 200-300ft below the ocean surface. These nets are suspended in the water column by weights and buoys, often left overnight. The mesh pattern is big enough for a fish’s head to swim into, but not its body resulting in the fish becoming entangled by its gills.

“Gillnets, like any type of gear, run the risk of becoming lost at sea,” says California Regional Coordinator with NOAA’s Marine Debris Program, Christy Kehoe. “So, some ways that gillnets become derelict are breaking free from floats, entanglement from the bottom surface and interactions and entanglement with, actually, other gear present just to name a few.”

In 2018, the Driftnet Modernization and Bycatch Reduction Act was passed in California in efforts to phase out large mesh drift gillnets in state waters by giving fisherman monetary rewards for returning their nets. Despite the progressive win, congressional action is still needed to ban them in federal waters. Following, in 2020 President Trump vetoed the federal bill on January 1st which would have worked to provide similar protections in federal waters over a five-year period as well as allow the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to support the commercial fishing industry in their transition to sustainable fishing gear.

In 2021, U.S. Senators Shelley Moore Capito and Dianne Feinstein reintroduced the bipartisan bill which was passed by the Senate this fall on September 14th. As of now, the Driftnet Modernization and Bycatch Reduction Act is under the consideration of Congress.

In a public statement in January 2021, Feinstein shared, “California is the only U.S. fishery that uses large mesh drift gillnets. Our bill would phase out these dangerous nets and help the industry transition to more efficient, sustainable and profitable methods like deep-set buoy gear. Testing has shown that 94 percent of animals caught with deep-set buoys are swordfish, resulting in far less bycatch than drift gillnets.”

One of the ways that Drift Gillnets are detrimental to marine life relates to the substantial impact from bycatch. Marine biologist and shark advocate, David McGuire, has explored the world producing media centered around ocean and shark conservation and awareness. McGuire is the director of Shark Stewards, an ocean health and shark conservation nonprofit that has contributed to the raised awareness of drift gillnets as an unsustainable and unnecessarily destructive fishing practice.

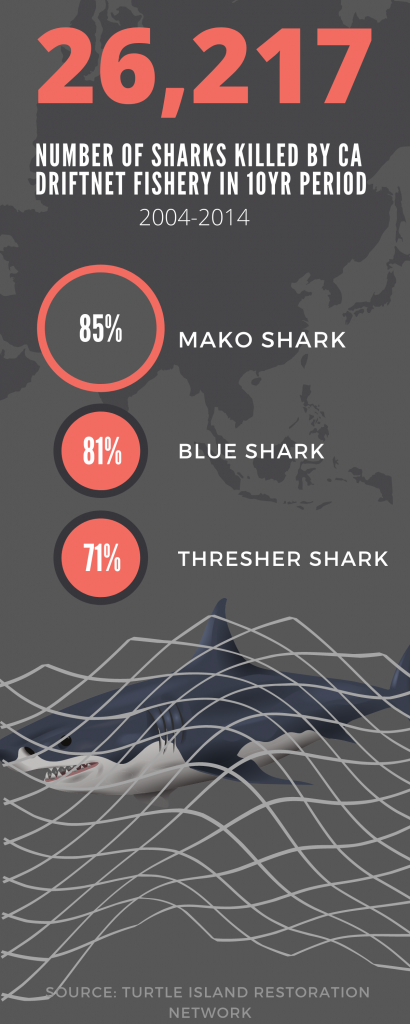

“Sharks are important to the ocean for many reasons. The large sharks are critically important as the regulators. As apex predators, they influence the trophic levels of the food chain below them. So, when you remove the apex predator, it’s like taking the roof off the house—the rain comes in and the walls fall down and then the whole system becomes degraded. By removing those species, you’re actually causing what’s called a ‘trophic cascade’ to the trophic levels below it and it disrupts the balance of that ecosystem,” says David McGuire.

McGuire reveals the severity of bycatch in regard to marine ecosystems by discussing the ripple effects of overfishing keystone species, such as sharks, and further removing important members of the animal food chain.

Sharks are the oldest living predatory animal on Earth. Within the coastal ecosystem, they are considered the top predator and keystone species. A keystone species refers to critical members within an ecosystem where, without them, the ecosystem could not survive. Sharks are one of the major species involved in drift gillnet bycatch and, because of their position as a keystone species, this has dyer impacts on other species in the marine ecosystem.

“Sharks are the surgeons, sharks are the sanitarians, they keep the ocean healthy and they take out the trash. So we need doctors and we need our sanitarians to have a healthy city, just like we need a healthy ocean and to have sharks, both the bottom sharks but also the apex predators like the white sharks, the oceanic whitetip’s and typically the hammerheads, the ones that are most critically endangered,” says McGuire.

David McGuire, Director of Shark Stewards

Drift gillnets have the potential to harm marine life even after they’ve been lost or abandoned. As part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program, Christy Kehoe works with partners of the organization to remove existing gear pollution as well as prevent the introduction of additional lost gear. In 2006 by an act of Congress, the program was established as the federal lead to investigate and prevent the adverse impacts of marine debris.

A major area of marine debris that the organization focuses on pertains to “ghost fishing.” Specifically, this involves lost or discarded gear that is no longer under the fisherman’s control and becomes lost, or derelict fishing gear, also known as DFG’s.

“Gear can become lost in many different ways, this can be intentional or unintentional with storms, propellers, and interactions with other fishing gear,” says Christy Kehoe. “But once this fishing gear is lost, it can contribute to catching the species its meant to catch, as well as catching nontarget species such as fish, crustaceans, birds and other animals that aren’t meant to be caught so we use this term ghost fishing to reference that it continues to catch even after its intention.”

Lost fishing gear can impact species, habitat and the coastal community in a variety of different ways. Derelict fishing gear can continue to catch target and nontarget species and part of this issue is tied to the entanglement of wildlife, which is a global problem that impacts a multitude of different species. When animals are caught in driftnets, it could be difficult to swim or feed and the nets often cut into the organism’s body, leading to death. As this fishing practice is indiscriminate, vulnerable populations such as protected or endangered fish, turtles and marine mammals have the potential to become ensnared and or killed, resulting in direct impacts on those already threatened groups.

Ghost fishing gear can also create navigational hazards and degradation to the surrounding environment, like fragile coral reefs. Lastly, ghost fishing can even have harmful influences on coastal fishing communities because the gear can be expensive to replace, and any marine life captured by the derelict fishing gear results in less target species caught, and therefore less profits made, by the fishery.

“…There was a time when these nets were made out of biodegradable cord, or string, you know rope, and it also limited the ability of how big the nets could be,” says director of the Turtle Island Restoration Network, Todd Steiner. “The modernization of this fishery so that these nets get pulled up by gigantic wenches, they’re now monofilament line, they don’t deteriorate over time, and they’re so much lighter that they can be so much bigger, those are the reasons why this fishery has grown to the point where it’s so unsustainable.”

Driftnets have the potential to turn into derelict gear through a number of different ways. Oftentimes storms damage and tear gear, and interactions with other debris in the ocean has also been proven to contribute to ghost fishing gear. Considering those factors in alignment with the fishing practices of local communities, Kehoe reveals that there’s a large dependence on where the fishery is, the type of gear being used as well as the kind of environment— meaning if the gear often collides and interacts with the ocean topography, such as reefs and rocky bottoms.

Toddy Steiner shares how the history of the west coast driftnet fishery reveals how the practice originally started in state waters, but because it was wiping out large numbers of marine life, the fishery moved out to federal waters. In attempts to address and minimize the harm of these driftnets, the fishery tried to put lights and pingers on them, they moved the nets higher and then lower, and they moved them farther from the coast.

“No matter where you put a giant, invisible net in the ocean, you’re going to kill marine life. That’s the bottom line, it’s indiscriminate, that’s the problem, it doesn’t just catch what the fishermen want to catch, but it catches lots and lots of stuff, it all ends up drowning underwater,” says Steiner.

Before the modernization of driftnets, fishermen in California used to go out to sea and harpoon massive swordfish, weighing from 800-1000 lbs. Swordfish would swim to the surface to thermoregulate, to warm up in the sun, and back then there used to be enough swordfish for fishermen to capture them one at a time. Driftnets became popular because they were less labor intensive, making them easier, and they were faster. However, over the years, the fishing practice has proven to be unsustainable because the numbers of swordfish are depleted, and the ones that are there aren’t anywhere near the size they used to be.

Steiner reveals, “[fishermen] used to catch more swordfish in California one at a time by harpooning them, than they now do by putting these massive nets out there for days and days at a time every year.”

The west coast driftnet fishery off the coast of California harms marine mammals, sea turtles, endangered species, it has high bycatch, the target fish is high in mercury making them unhealthy for people to eat, and the nets contribute to ghost fishing.

The economic arguments against these driftnets describe how the amount of money spent by taxpayers to manage, and regulate, the fishery and to conduct all the various environmental impact reports, is more than the income recovered by the fishermen who fish, according to Steiner.

“Of course there’s going to be a short-term impact on the actual fishermen themselves…” says McGuire. “Until they’re able to get this support, they may suffer some down time and they already have—there’s been increasing regulations over the years because of lawsuits brought on by environmental groups from the Endangered Species Act being violated.”

The fishing community has already been experiencing a ‘squeeze out’ by conservationists and activist groups in the past decade. Today, there are less than half of the number of fishing boats used to capture swordfish.

There are also ecological impacts to outlawing the use of drift gillnets in federal waters because of the impact of removing apex predators. McGuire tells how both swordfish and sharks are apex predators, meaning they’re at the top of the food chain and because of their position among the trophic levels as predatory species, their bodies retain higher amounts of methylmercury due to bioaccumulation in the ocean.

“…The larger the animal gets, the more it bioaccumulates or even biomagnifies toxins that they’re not able to excrete,” says McGuire. “So methylmercury is a perfect example, the larger the tuna, the larger the swordfish, and the larger the shark, the higher the amount of methylmercury that fish will retain in its fat cells, or fat tissues. And when we eat that, whether it be a tuna or a swordfish or a shark, we’re getting a dose of methylmercury which is…a neurodegenerative toxin.”

Ingesting methylmercury through the consumption of marine animals like swordfish, shark, and even in some cases species of larger fish, poses serious health risks, particularly for pregnant women and children.

Alongside methylmercury, people also have to consider organotoxics, where plastics in the ocean absorb onto other larger pieces of plastic, and of which are being eaten by marine organisms and therefore contributing to the bioaccumulation throughout the animal food chain in the ocean.

“It’s so bad now unfortunately, especially with some of the plastics and pesticides that have been put into our ocean, that when an orca whale or a killer whale dies, it’s considered toxic waste under the Hazardous Waste Act (1972), because it’s such high concentrations of these toxins so it’s unfortunate that we’re doing this to our ocean and if we’re eating this fish, we’re doing it to ourselves.”

David McGuire, Director of Shark Stewards

Another argument made against the drift gillnet fishery, relates to the existence of substitution gear. The Driftnet Modernization Act, currently being considered in Congress, acknowledges the creation of sustainable alternatives to driftnets, like the deep-set-buoy gear. Considering that the deep-set gear is still in an experimental phase, however, the sustainable alternative uses a hook-and-buoy system that attracts swordfish with bait and alerts fishermen immediately after a bite is detected.

According to an article from the Turtle Island Restoration Network, gear testing has shown that 94% of animals caught are swordfish. This also means that the new sustainable gear will minimize bycatch because of its efficacy with capturing the fishery’s target catch.

“The deep set longline…will create significantly less bycatch – something like half or more, and the fish won’t be as damaged,” says McGuire. “So, the swordfish is actually worth more, in the deep set buoy gear than it is in the drift gillnet—almost twice as much. So the same fish, they’ll get twice as much money and less effort…It’s predicted that it will bring in something like 42 more jobs- or boats coming online, a 20% increase in revenue, and more tax money. ”

The hope among conservationists and environmentalists is that the Driftnet Modernization and Bycatch Reduction Act will be approved by Congress, and then move to President Biden for his signature to make it into law at the end of this year, in 2021.

To help support the passing of the bill, experts advise reaching out to your representative in the House of Representatives and demanding they support and vote for the bill.