Digital Blackface: The New Face of Blackface

Blackface is known to take the form of darkened skin, overdrawn red lips, and curly fros, but today Blackface is back but this time — digitally.

The Origin of Blackface

Traditional Blackface originated in the 1860s after the civil war as a way to dehumanize and ridicule Black people in America. Many people think that Blackface is largely a phenomenon of the past, but the internet has allowed for a resurgence of Blackface particularly seen through social media apps.

“Digital blackface,” a term popularized by feminist writer and University of Chicago doctoral candidate, Lauren Michele Jackson, is the “practice of white and non-Black people making anonymous claims to a Black identity through contemporary technological mediums” (The Awl). These depictions are commonly seen through reaction GIFs, social media avatars, and the frequent use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

The New Face of Blackface

University of Southern California student, Amy Lopez, believes that digital Blackface manifests on social media apps like TikTok where users emulate the language and actions of Black women through the use of soundbites.

“A lot of the instances I have seen on TikTok are white girls using audios of Black people. I’ve noticed most of the time it happens to be Black women rappers, and they tend to make very exaggerated movements or gestures that they wouldn’t typically make in any of their other TikToks, so it suggests to me this is their depiction of Black people. This is what they believe Black people to act like,” Lopez said.

USC senior Nailah Patrick, is active on all social media platforms and has seen a proliferation of digital Blackface on all social platforms but specifically on Instagram, where non-Black influencers gain massive followings for appropriating Black aesthetics. Examples of this appropriation include the rise in the Brazilian Butt Lift surgery that adopts the body type that Black women have historically been scrutinized for.

“We don’t get a choice, whether or not we want to have a big ass or certain other stereotypes. We are brown. This is how we look versus for them, it’s for the aesthetic, and they get to choose to put themselves in our position. Because we don’t have a choice, as a result, Black people stay scrutinized and over-sexualized for their body,” Patrick stated.

While the dominant culture often profits off of elements of Black culture like the aesthetics of their body, the Black community has historically responded to theft with innovation. Eric Deggans, a full-time TV critic at National Public Radio (NPR) discussed this reaction of innovation.

“I think one thing that Black culture has always done is it’s always innovated. It’s always about finding new expressions and new ways of taking what we have and turning it into something that is really cool. As long as we keep doing that then mainstream culture will keep dipping into that and taking from it,” Deggans said.

The Appropriation of Black Language

Ultimately, the harm in digital Blackface derives from the impersonation by non-Black individuals who are trying to emulate a sense of “Blackness” without actually being aligned to the realities of the Black identity. In fact, the adoption of Black culture from the non-Black majority has become so commonplace in the younger generation that the use of AAVE, a language created by African Americans has even become synonymous with the “Gen Z” language.

Amanda Elimian, who has a YouTube channel with over 200,000 subscribers, frequently discusses social issues related to media on her channel. Elimian believes that a part of the reason people may fail to see the harms of adopting language from AAVE is that they do not take Black people seriously.

“They’re not taking AAVE or Black people seriously as having their own culture — and I mean, it’s cultural to Black people and Black people only — you think you can just take and grab certain things you hear because you like them, or you say, ‘I saw this person online saying this word, I’m going to start regurgitating it,’” Elimian said.

Equating AAVE to slang or Gen Z language has become so habitual that in a recent SNL skit called “Gen Z” hospital, cast members appropriated the real language of AAVE and minimized it to a simplistic form of mockery for comedic relief.

Rafiat Animashaun is an account executive at Vanguard Communications as well as a Master’s student in public relations and advertising at the University of Southern California. Animashaun views the appropriation of language as harmful as it minimizes the real language that millions of Black people use every day.

“They’re mocking the way in which Black people talk every single day and that’s because it’s translated to social media and people think that’s how people talk on a regular day. No, there’s meaning. There’s context,” Animashaun said.

The effect of disregarding context from the language used on social media can devalue Black people to a type of entertainment.

Derek Blackwell, a professor at Praire View A&M University has researched digital media for the past years and currently focuses his research on hip-hop and Christianity. Professor Blackwell emphasized the harm in decontextualization of language on the lives of Black people.

“It can be exploitative, I think in certain contexts, and I think it can also be offensive and demeaning too. It can make someone feel like a token or like a mascot of sorts as opposed to the whole sort of being,” Professor Blackwell stated.

It is important to acknowledge that there are certain contexts where speaking AAVE is seen as acceptable and even “cool,” while in other contexts it can be seen as an unprofessional and inferior way of speaking. However, non-Black people speaking the language of African Americans was not always seen as cool.

In fact, as Blackwell describes these AAVE phrases were “markers of inferiority in the eyes of some white communities that then get flipped into cool and reappropriated as ‘okay, we kind of like have this now.’ But then when it manifests itself in a different context, like a job interview, then it goes back to being what it was before, which is a marker of inferiority in their eyes,” Blackwell said.

An article published in Refinery 29 titled “Be Your Authentic Self At Work — But Only if You’re White,” exemplified the inequitable disparities many Black people face in the workplace for being themselves.

Journalist Ludmila Leiva said that “Professionalism has long been a synonym for whiteness, especially given that dreadlocks and other natural Black hairstyles, the use of Spanglish, Chicano English, or African American Vernacular English (AAVE), and many other non-white cultural signifiers are routinely flagged as inappropriate in the workplace” (Leiva).

Source: YouTube

When non-Black people simply choose to appropriate the language of Black people without fully understanding the privilege of falling back into their racial privilege, the authentic identity of Black people (that cannot be taken off) is disregarded. Furthermore, there are diverging perceptions of Black people who conform to certain elements of African American culture and non-Black people who simply adopt it.

“Very often not to toot our own horns, but very often Black culture is the impetus for anything that is cool. And when we do it, it’s tacky, it’s ghetto, it’s this, that, and the third. But once you transition to a white celebrity or white creator, then they’re like, ‘Oh, this is cool, this is innovative, this exceptional.’ It’s always been some type of Blackface with this society and we’re just transitioning into online,” Animashaun said.

The Tie Between Black Culture and Hip-hop Culture

While the appropriation of elements of Black identity by non-Black people can be viewed as a type of theft, a lot of what we conceive as Black culture is actually rooted in hip-hop culture. Therefore, there is a complex component of ownership when considering what we label as “Black culture.”

“A lot of what we recognize as Black culture in language and things like that is equal parts hip-hop culture and so then it becomes a matter of how we understand the ownership of culture. Hip-hop culture is deeply rooted in Black culture but now exists in such a mainstream accessible way that you have people of all racial and cultural backgrounds embracing it and identifying with it and using it in their own everyday lives,” Professor Blackwell said.

Since hip-hop and Black culture more generally, are now experiencing significant societal appeal, it can be hard to delineate the line between appropriation of identity and appreciation of culture. However, just like traditional Blackface, Digital Blackface is a choice.

“It’s not something that you just like do off a whim. You’re not just emulating Black randomly. You’re not kind of pushed into Blackness. You made a conscious choice to not act as yourself on the internet, but to act as what you thought was cool or different, which is Black,” Elimian said.

The Impact of Decontextualization

While it is almost impossible to know the context behind every GIF, soundbite, or meme, it is important to acknowledge the impact of this ignorance on the real lives of people within media. Animashaun details the experience of a popular GIF that circulated on social media involving a Black woman turning away in disgust. People would use this reaction GIF frequently without being aware of the circumstances of the situation until the woman in the video explained it.

“A few months later there was a video of her explaining what had happened. And this was during a moment when the London towers collapsed down and there was a fire. Hundreds of people lost their lives in that space because there wasn’t adequate equipment,” Animashaun said.

Animashaun admits that even she had used the reaction GIF when communicating but was not aware of the pain behind the digital face.

“People just see this funny reaction. But there’s a whole other traumatic tragic context. So imagine that person seeing her face consistently at that moment in the darkest point of her life being used in comical settings. And I think that is one of the harmful ways in which digital Blackface takes those moments, removes the context, and makes it sanitized to work for certain situations,” Animashaun said.

The decontextualization of media elements involving Black people is a growing occurrence. A sound bite on TikTok used the audio “Damn, double homicide” and went viral as a trend used to emit a sense of comic relief while disregarding the real situation of the audio. The audio involved a Black woman on a reality show, crying while describing her traumatic experience aborting twins. Someone in the back yelled “Damn, double homicide” in reaction to her disclosure.

“When white women have their videos, like their trauma video taken out of context, it’s an automatic ‘we have to take this down’ because it’s not right to do that to anybody, but it’s a very different reaction when it’s a Black woman,’” Elimian said.

The Mindset Behind Digital Blackface

The pain of Black people, specifically Black women is a problem that transcends digital Blackface. In fact, the mentality of disregarding Black pain can lead to fatal outcomes.

“I’m in medical school and we learn that people really don’t believe that Black people can feel pain to the exact same degree as white people and you’re just becoming desensitized to that. It’s not just the internet, people on the internet are people in real life,” Elimian said.

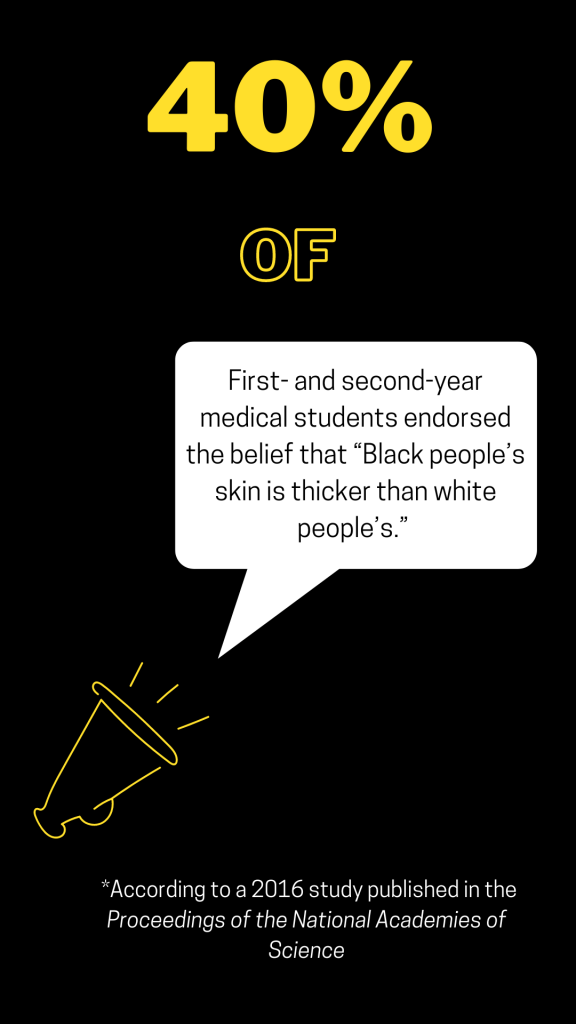

These people on the internet become doctors, lawyers, and police officers that impact many institutions within American society. A paper published in The New England Journal of Science and Medicine titled “Taking Black Pain Seriously,” examined the origin of minimizing Black pain.

Doctor Oluwafunmilayo Akinlade states that a “2016 study details the ludicrous yet common belief among medical trainees that Black people have a higher pain tolerance than Whites, perpetuating 19th-century slaveowner Dr. Thomas Hamilton’s fallacy that our skin is ‘thicker,’ made up of fewer nerve endings, and hence less sensitive” (Akinlade).

The belief that Black people do not feel pain in the same way as white people is another parallel to the racist foundations of the original conception of Blackface. Therefore, the impact of this mindset demonstrates that despite its name, digital Blackface does not stay digital. The implications of the mindset behind this appropriation can and does expand to more serious sectors of life.

“If you think you’re Black on the internet, what’s stopping you from trying to act Black in real life?” Elimian said.

What Does it Mean to “Act Black”?

It is also important to examine what “acting Black” even means. Certain phrases in AAVE like “finna, period, and cap” are indicators of a type of Black identity that has been co-opted digitally. However, there are many aspects associated with the digital Black identity that perpetuate negative stereotypes of “Blackness.”

“I think the overarching reason why people use digital Blackface is to seem not empowered, but almost aggressive. When they use AAVE terminology, it’s to be caddy, to be aggressive, to be in somebody’s space. It’s not often used to be friendly or cordial or like, ‘Hey girl, what’s up?’ It’s always in this aggressive attacking manner,” Animashaun said.

Furthermore, Animashaun elaborated that when people only encounter these online personas of Blackness that are often inauthentic to the reality of Black people, there is a real threat of misrepresenting entire identity groups.

“If you live in a place where you never run into a Black person or a white person, an Asian person or Hispanic person in your life, you’re going to turn to media — either social or traditional media to get an idea of what that culture is, what people of that community are… So if you see people with a profile pic that looks Black, they speak a certain way, they talk a certain way and you read it or you feel it’s aggressive towards you, it’s attacking you, you will automatically assume like, ‘Oh, well, I’m guessing Black people talk like that,’” Animashaun said.

However, the perception of Blackness is deeper than an assumption of the way Black people talk, many people will use these construed Black identities to create entire narratives of Blackness that minimize Black people to a form of entertainment.

“Being Black is more than just about being entertainment in America. What’s happening is people are picking and choosing when they want to acknowledge or steal from Black culture. The thing is that just simplifies our story because it muddles up what representation and storytelling should look like for Black people ’cause it’s more than just entertainment,” Patrick said.

Our current media landscape upholds “Blackness” as a type of cool trend to observe and adopt. However, as Patrick further notes, Black people’s lives are not a show.

“Black people are not just singers and not just athletes or comedians. They have a life in reality, but to some people, our experiences may be just politics, but to us it’s our reality. So that’s something that also needs to be told, not just when it’s convenient or when our face looks relatable,” Patrick said.

Some may ultimately contend that the appropriation of Black aesthetics actually helps Black people become more accepted in the dominant society. However, in a society that still sees Black culture on Black people as inferior to Black culture on white people, the “appropriation doesn’t reduce racism that much because the world has already decided to treat Black people differently,” Deggans said.