As she read the blog post, she knew something needed to be done to help the Bruce family. She recognized all the typical hallmarks – the racism, the redlining, and the property stripped away from a thriving, successful Black enterprise. So she got to work.

Ward’s activism is unrelenting: she always commits 100% to her justice efforts. While living in Washington, D.C., Ward went “back into poverty” thanks to a five-year legal battle with an organization and former employer who she (and other employees, all part of a class-action lawsuit) accused of racial discrimination. Despite being lauded for her bravery, Ward says she was “blacklisted” off of every other job in the city. It was an exhausting experience for her, only Ward’s poetry kept her grounded through the tumultuous times. She decided to move to California, “hoping to get away from the activism.”

But as Kavon Ward will readily tell you: “as a Black person in America, activism is essentially always a part of your life.” And though she hoped for respite on the west coast, America caught up to her. This time, with the murder of George Floyd. Sitting at home, in COVID, Ward felt the same overwhelming anger and frustration shared by so many Americans. In the “Facebook Mom groups” she was a member of, Ward watched her friends’ voices silenced over claims of being “too political.”

“This is not political, this is personal,” she said. “My people are dying, you know?”

So she and a group of those friends started the “Anti-racist Moms” group (later “Anti-racist Movements”) in the South Bay of Los Angeles. Their goals were initially broad, but a pair of blog posts about the Bruces and their Beach focused Ward’s anger in like a laser.

“I read about it, and I just felt that fire again. That fury bubbling back up,” she said. “I said, ‘We need to do something about this.’”

It started humbly: the group held a picnic at Bruce’s Beach on Juneteenth of 2020. A little over a year later, on September 30th, 2021, Governor Gavin Newsom would be standing at that same spot – thanking Kavon Ward specifically for her activism in helping to return the land to the descendants of the Bruce family.

It was a busy year for Ward, between petitioning politicians like LA County Supervisor Janice Hahn and spreading the word online about what had been done to Charles and Willa Bruce. In the end, it was Senate Bill S.B. 796, introduced by State Senator Steven Bradford, that finalized the return of the land to the Bruce’s descendants. Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law at Bruce’s Beach on September 30th, and offered the apology, “that the city of Manhattan Beach won’t.”

Today, the property is worth roughly $75 million dollars. Bruce descendant Anthony Bruce told The Guardian that the return of the property to his family was “a reckoning that has been long overdue.”

That return itself was almost entirely unprecedented, but the speed with which it was achieved was something that Kavon Ward and Where is My Land organization partner Ashanti Martin never predicted.

Ward chalks it up to several factors. “I think it was a timing situation,” she said, “I think it was a spiritual situation. I think it was a squeaky wheel situation. But for the most part, I think it was a timing thing.”

That timing means the success isn’t all wine and roses. Both Ward and Martin reflected on the conflict they feel about their success being indebted in some part to the death of George Floyd.

“Obviously, it’s a tragedy for him to die the way he did, at the age he did,” said Martin, “but I think his death has really resulted in seismic shifts in this country.”

Compounding that conflict is the inherently exhausting nature of activism, a job which is too full of thankless moments and inherited trauma.

“It’s not just messed up with George Floyd being the catalyst,” said Ward, “It’s also messed up how much trauma activists have to deal with in order to get justice. You know, there was a lot of resistance from Manhattan Beach, from the people of Manhattan Beach, but people don’t realize the impact resistance has on the people fighting this fight.”

Martin and Ward are aware that they alone will not be able to carry out the fight.

“This is not sustainable,” said Kavon Ward. “We’re all volunteers. It’s not sustainable to expect people to work their full-time jobs and earn a living, and do this work, and raise kids.”

But weariness hasn’t held back Ward and Martin, whose new organization Where is My Land has been receiving hundreds of inquiries from Black Americans all around the country who believe they or their families have been similarly wronged. It’s an astonishing burden to imagine any few people shouldering, but Martin says Where is My Land hopes to be merely a piece of the overall movement (albeit the catalyzing one). With Martin in Philadelphia and Ward in Los Angeles, the organization quite literally has its sights on the entire country.

“It’s very important for us to spark a movement, keep the movement going,” she said. “We need people to not look at these instances as, as discrete cases, as unique stories of injustice. Because well, honestly, it’s just a piece of a story of injustice. We need to show that land taking was indeed systematic, and had systematic impacts for Black Americans for generations after the thefts.”

While some might classify their work under the umbrella of reparations, Martin says it should be separated.

“It’s unequivocal. There are records and there are documents and witnesses, and it affects individual people and individual families,” she said. “Really, it’s not even a matter of reparations and ‘what is owed,’ it’s a matter of theft. And what should be given back as restitution.”

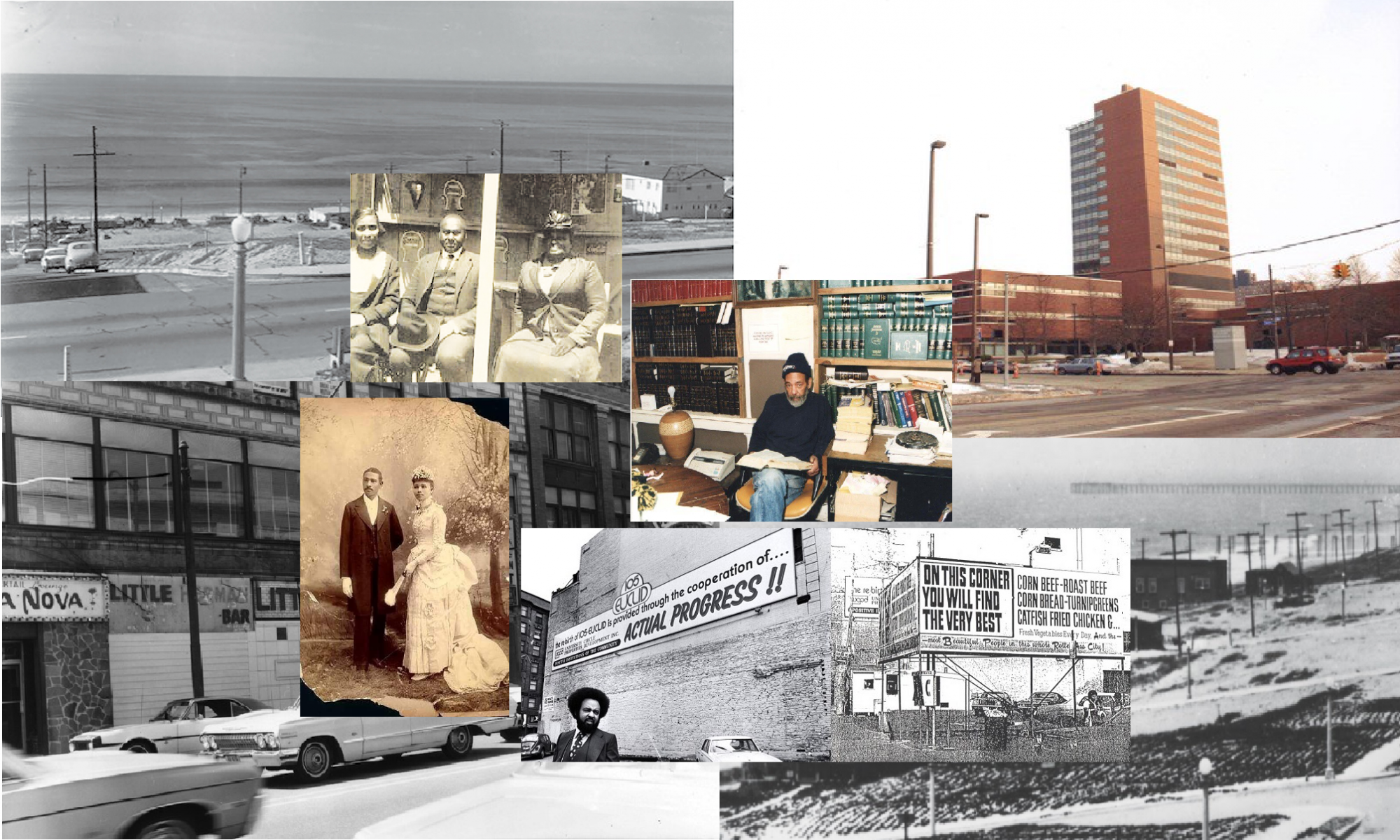

The Winston Willis case, which came across the desks of Where is My Land in April, fits that mold perfectly.

“It’s disgusting,” said Ward. “Some of this man’s land was taken at gunpoint. Some of it was taken while they threw him in jail. The Cleveland Clinic better be ready. We’re gonna lay it on them thick.”

Ward summed it up: “You’ve got Black entrepreneurs being told their whole lives, ‘Pull yourself up by your bootstraps, pull yourself up by your bootstraps,’ and they do. And then the boots are stolen, and the straps are stolen. They take everything.”