But Willis wouldn’t leave. He sat in an abandoned lot across the street – the SWAT team sent by the city wouldn’t allow him to watch on the property – and saw the last remnant of his former empire reduced to rubble.

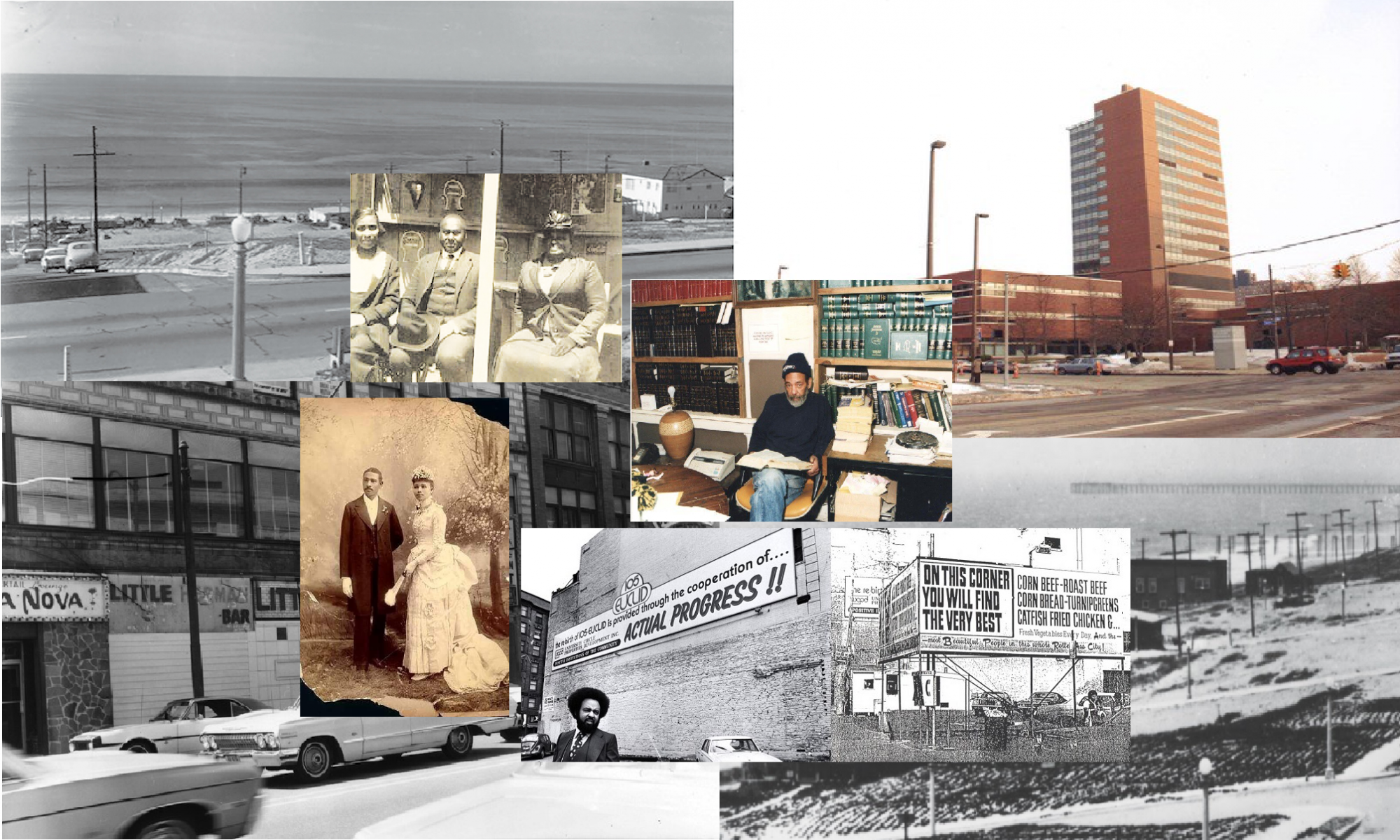

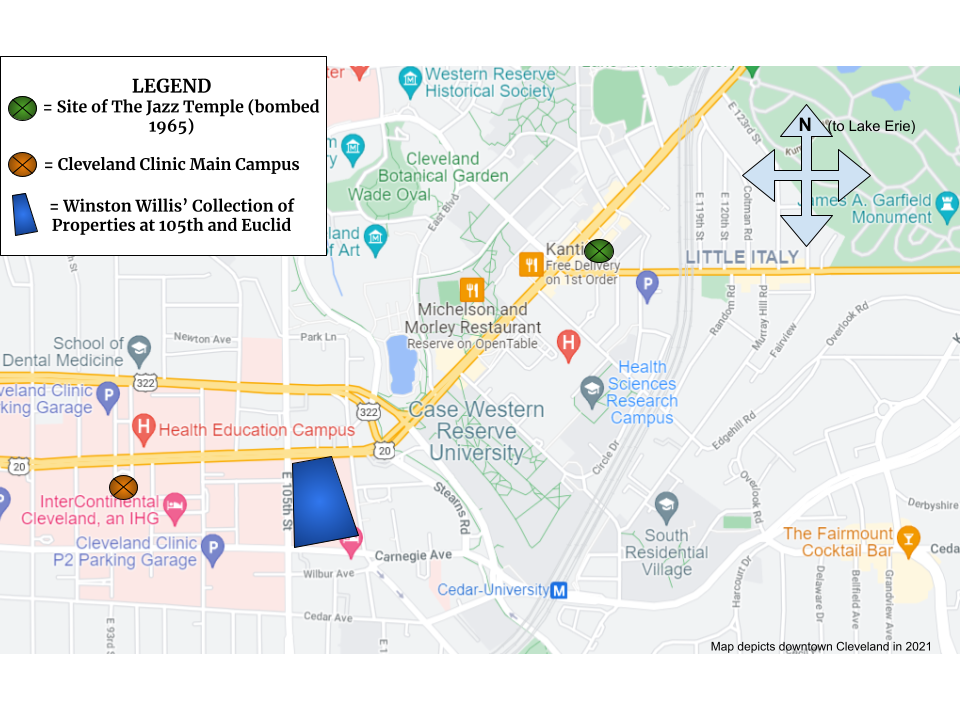

Decades prior, the building had been a warehouse, the place where Willis stored the kitchen equipment for his various other enterprises. They were many, over the years, and included restaurants, theaters, arcades, clothing stores and more. All in all, Winston Willis ran about 30 businesses and employed roughly 400 people at his peak in the 1960s and 70s. Most of those employees were people of color from the downtown communities Willis’s businesses had rejuvenated. Folks called his blocks an “inner-city Disneyland” and “Winston Willis’s Miracle on 105th St.” Among his community, he was revered as a local icon and symbol of unabashed Black pride, success and resistance.

Winston Willis had been a businessman since his childhood. As young as four, he’d worked out a deal selling candy door-to-door on behalf of an old widow. His family were part of The Great Migration, leaving their Montgomery, Alabama home and heading north to Detroit. There were five Willis children in all: Winston, at age 15, was number three.

While he started a business in town – a local advertising circular called the Western Detroit Shopping News – the Detroit public school system didn’t hold much luster for young Winston. It also didn’t help that he’d discovered the pool hall on his long walks to and from the high school. He dropped out in tenth grade and dedicated all his efforts towards pool and craps, quickly becoming very skilled. At age 19, he moved to Cleveland to make his fortune.

Two extremely important things happened to Winston Willis on his very first night in Cleveland. First, he met and befriended Carl Stokes, the future mayor of Cleveland. Second, and perhaps most importantly: he won big. $35,000 big, to be exact, shooting pool. Willis took the money and began investing in his business plans.

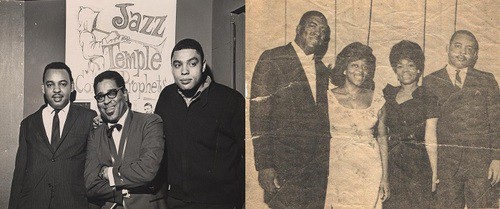

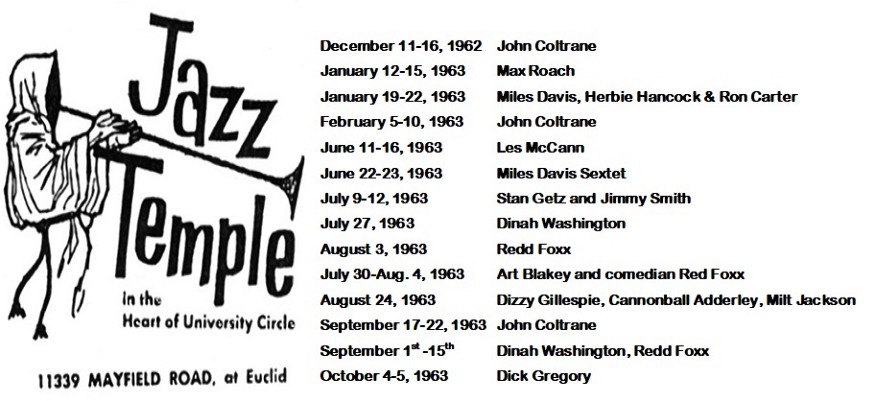

In 1961, Willis opened The Jazz Temple. It was a coffee house/nightclub, directly adjacent to Case Western Reserve University, featuring live jazz and free thinking. Many greats, including Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Dizzy Gillespie were known to frequent the Temple, and it was seen as somewhat revolutionary in the heavily racially-polarized Cleveland.

Aundra Willis Carrasco, working at the Temple as a cocktail waitress for her brother, remembers the pioneering nature of the club.

“There was a lot of interracial dating, so the neighbors didn’t like that. We would get bomb threats all day long,” she said. “I would say, ‘Winston, do you know what they just said?’ He would just say, ‘Hang up the phone, hang up the phone.’”

The terror was unrelenting – if the racial hate wasn’t enough, the property was also directly adjacent to the territory of the Cleveland mafia. Several bomb threats turned out to be legitimate, with one early morning explosion finally bringing the building down in 1965. Fortunately, no one was inside the club at the time, and Willis’s spirit remained indomitable. He continued his other endeavors and in 1968, Willis finally had another turn of good luck. He won a three-day crapshoot, netting a lucrative half million dollars and affording himself the opportunity to buy up the properties around the intersection of Euclid and 105th.

They were properties which had been largely abandoned by white storeowners following rioting in the mid 1960s, allowing Willis to purchase significant chunks at once and further the reach of his growing empire. In tandem to his own personal success, he revitalized a previously defunct neighborhood. While some of Willis’s businesses were certainly adult-oriented – at times he was referred to as Cleveland’s “Pornography King” thanks to his adult cinemas – 105th and Euclid maintained a reputation as a relatively safe place for shopping and recreation thanks to the bouncer population Willis hired to enforce security at almost all of his establishments.

Unfortunately for Willis, while the property had little value to the white storeowners who’d previously occupied the space, someone else had their eyes on it. That someone was the Cleveland Clinic, a hospital of international renown and Ohio’s medical jewel. In Cleveland, no one entity has as much power as the Clinic – beyond the city itself, it’s the single largest employer in Ohio and brings billions of dollars into the state.

The Clinic’s goal was to connect their main campus with nearby Case Western Reserve University. The plan was simple, except they had forgotten to account for the iron will of Winston Willis. Willis had no intentions of selling, so he alleges the Clinic turned towards the power of the government and eminent domain law to steal away his land.

However, from 1967 to 1971, Winston had a friend on the inside. His pool buddy, Carl Stokes, was mayor of Cleveland, and would “deflect every attempt” to sequester the 105th and Euclid properties away from Winston Willis. Though they would avoid being seen in public together, the continuation of that friendship offered Willis a few solid years of relatively unaffected growth and prosperity. His net worth ballooned, and Willis began to dream of national and even international expansion.

But then Carl Stokes announced he wouldn’t be running for re-election, and some far less-sympathetic forces came into power. Over the next two decades, there was a string of mayors with no interest in protecting Willis’s property. First came Ralph Perk, who some believe used the Clinic expansion as a mere ruse to oust Willis and his indomitable nature from the area. Later would come George Voinovich (mayor from 1980-89) whom in particular seemed eager to have Willis completely removed. Both Winston and Aundra Willis allege that Voinovich had a special vendetta for Winston, having rubbed elbows with him during his time serving under also-unfriendly mayor Dennis Kucinich (whose tenure ran from 1977-79). Both, allege Willis, were more than willing to help the Clinic clear out his properties throughout their tenures.

In 1977, Winston Willis filed a $100,000,000 lawsuit against parties including the Cleveland Clinic, the City of Cleveland itself, and members of the government over the seizure of his land. However, he found no favor in the local courts, and spent decades appealing and re-appealing the decision.

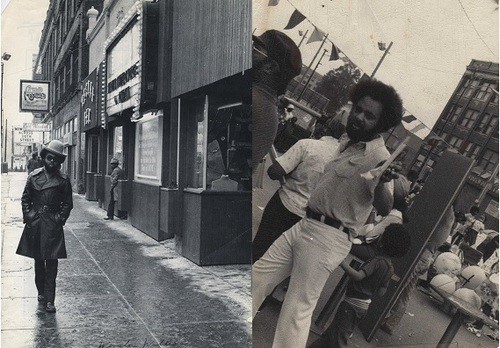

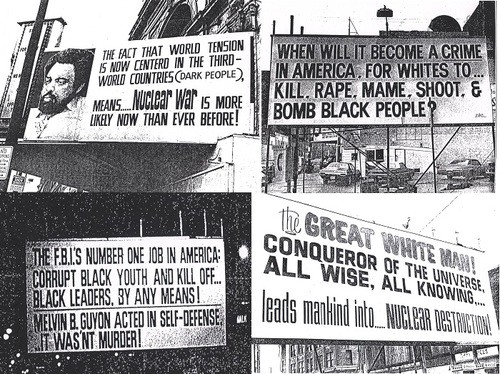

From the start of his post-Stokes fight in 1972, Winston Willis knew the strength of those who opposed him. Still, he wasn’t afraid to stand up to them. In fact, Willis seemed almost to relish fighting “the man,” according to his friend Mansfield B. Frazier. Willis’s well-known Black pride was terrifying to the white establishment of Cleveland, a fear only compounded by Willis’s famous billboards.

As soon as the powers that be started coming for him, Willis had his construction crew set up a huge billboard overlooking Euclid Avenue. He would rotate all caps, no-holds-barred messages across the signage, with slogans like, “WHEN WILL IT BECOME A CRIME IN AMERICA FOR WHITES TO KILL, RAPE, MAIM, SHOOT, & BOMB BLACK PEOPLE?” Willis’ billboards quickly became a cultural landmark for the Black community in Cleveland, and the man himself was elevated to folk hero status. Here was a young man unafraid to stand up to the powers that be, unabashedly pro-Black, wildly successful, and cool as could be. Winston Willis, driving around Cleveland in his white Jaguar convertible, was an icon.

The fight, despite Willis’s tireless efforts, was futile. His last billboard, before the properties started to go, read: “Farewell Friends & Neighbors. After 10 years serving this community, soon we must close our businesses to make way for…UCI — Cleveland Clinic — State of Ohio…To Build a New Hospital — for Whites.”

But he had made an impact, before they had been able to shut him up. One of Willis’s billboards even revealed, to some public outcry, that the Cleveland Clinic had no Black physicians on staff whatsoever, resulting in the Clinic’s first Black doctor being hired. The Cleveland Clinic has a history of classism and racism, refusing to administer care to Black folks as recently as the 1950s, and has a reputation for neglecting its surrounding neighborhoods. In 2017, the Cleveland Clinic also came under fire for its “persistent financial support” of President Donald Trump.

Even after he had lost his lawsuit, and properties had begun to fall, Willis didn’t give up his fight against the government and the Clinic. He began studying law in hopes of finding salvation in a legal code which had previously offered him so little, and petitioned the highest courts in the land to hear his case.

Winston Willis was also arrested in 1982, over an alleged bad check he had written for $400. The fact that his CFO had signed the check, it seems, was secondary – Willis was the target. He alleges his banker, John Bustamante, was being blackmailed to tamper with his accounts; although no such blackmailing has ever been proven in a court.

Regardless, they came for Winston. They took him to five different detention center, Winston says, because each Warden would refuse to hold him on account of lack of evidence. However, at the fifth jail, says Willis, the warden received a phone call and immediately proceeded to lock him up.

Just a few days later, says Willis, he was approached in his cell and placed in solitary confinement. When prompted for a reason for his punishment, Willis says the guard had no response. They put him in the hole for ten days. During those ten days, the city cordoned off and bulldozed a huge chunk of Willis’s remaining properties. They didn’t want to wait for Willis to give up the fight, it seems, and decided it would be easier with the man well and truly silenced (if only temporarily). The Cleveland Clinic expansion finally was able to move ahead as it had been planned two decades prior. Willis kept fighting, trying to hold onto the few properties he had left, but it was to no avail. When the final warehouse fell, so too did Winston Willis’s last residence. He became homeless in the city where he’d once been a prince among men, under the glass and steel of the Cleveland Clinic.

Aundra Willis Carrasco, though she’s sinced moved from Ohio, knows the Clinic as “the very citadel of power in Cleveland.”

“They own it, they manage it, and everyone in Cleveland is in their grip,” she said. “I know for a fact.”

Aundra does know plenty about her brother’s fight with the government and the Clinic: she’s been helping him fight it for the past 20-plus years. A writer by trade, Aundra stopped up at her brother’s place on Halloween weekend, 1999, in order to help him draft his petition to the Supreme Court. She ended up staying with him for four years, and has been tirelessly telling Winston’s story anywhere she can ever since. In Cleveland, Aundra alleges, the story has been repeatedly hushed by the Clinic.

“The Clinic has all the local media in their grip, and they will not cover the story. I have relatives that live there, and it’s not being seen or talked about anywhere,” she said.

The Clinic, when contacted, chose not to comment on the allegations made .

Even throughout the rest of the nation, Aundra says she struggled to find truly interested or sympathetic parties. That is, until April of 2021, when she was put in contact with Kavon Ward at Where is My Land – someone else unafraid to stand up to the Cleveland Clinic.

Today, Winston Willis is in an assisted living home with early onset dementia. However, the fight is not over, even if the goals have changed slightly. There is no way to recover that which was taken from Willis and his progeny, and no one knows that better than the man himself. Now, he and his family would just like to see the Cleveland Clinic’s W. O. Walker Building, standing atop the remains of Willis’s former empire, returned to the community it was taken from. They want to see it as a community health center, not an elite oasis.

The story of Winston Willis is a true tragedy. The man was not been an angel, as he will readily admit, having plenty of personal troubles with relationships and family. And while he was a symbol of Black success, he wasn’t on the cutting edge of any civil rights battles. As Mansfield Frazier remembers , “his goal as far as I could tell was to advance black accomplishment only to the extent to which it applied to him — increasing his wealth.” Still, Winston Willis was able to accomplish something that most Americans only dream about and inspired plenty of others along the way, only to have it ripped away from him by racism and the powers that be. The promise of the American Dream feels miles away from stories like his.