But this is not just any city park beach. Right here, on this same land where picnickers are now eating their food truck lunches and watching surfers slice across their waves, lies a long-repressed, dark history. One full of violence, hate, and racism.

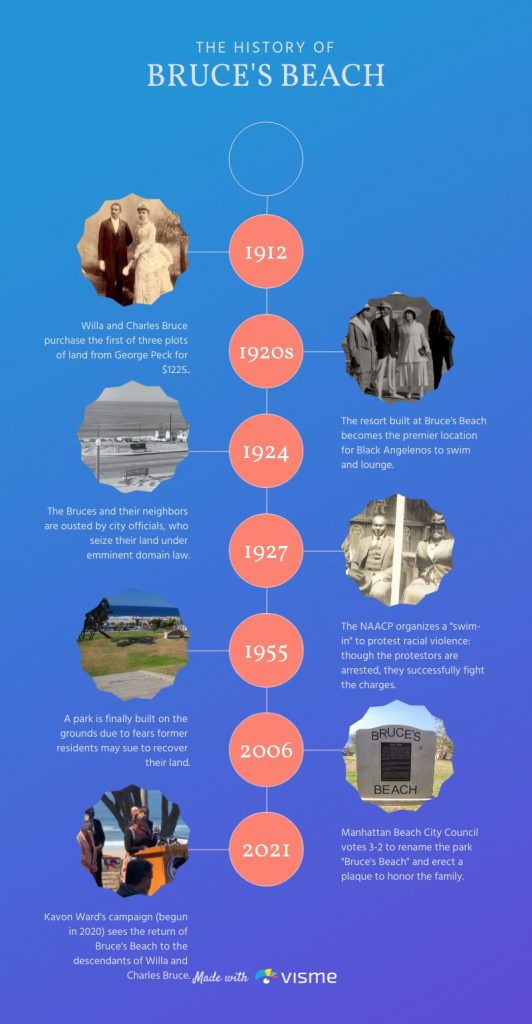

Los Angeles, 1910s-20s. Under the brand-new Hollywood sign, the city was racing forward into a new, golden era. It was a promised land, full of brand-new opportunities and prosperity. Newlyweds Charles and Willa Bruce were looking to secure some of that prosperity for themselves. In 1912, They bought some oceanfront property in the recently-established Manhattan Beach community for a little over a thousand dollars and opened a resort.

If you were a Black Angeleno in the early 20th century and you wanted to have a day at the beach, there’s a damn good chance you went to Bruce’s. It was one of only a few places in the city where you could swim and lounge freely, without fear of persecution – until it wasn’t.

Unfortunately for the Bruces and their customers, their success and geographic location had made them some jealous, hateful enemies. Worst of all – these enemies were powerful. Some residents of the newly-incorporated Manhattan Beach, the project of millionaire real estate mogul George Peck, were more than a little uncomfortable with the Bruce’s success. The city also had a very active chapter of the KKK, whose harassment of the Bruces and their guests included slashing tires, barricading other sections of the city to potential visitors, and attempts at burning down the resort. Once, they even tried to blow up a gas meter. The phone seemed to always be ringing off the hook – the threats wouldn’t stop.

But the Bruces hung on. Or they did, at least, until a white realtor named George H. Lindsey (who, unsurprisingly, had a hood and robe hanging in his closet) brought a proposal to the city’s Board of Trustees. He had found a loophole, he claimed, wherein the city could use Eminent Domain law to weasel the Bruce’s land away from them – all under the guise of using it as a park. The Bruces and their Black neighbors had no options to fight. Powerless, the Bruces accepted the small sum of money offered to them by the city – a fraction of the property’s value. Then, they got the hell out of town.

For decades, the property sat abandoned, until a park was finally built on the location in the 1950s over fears the Bruces and the neighbors would sue to recover the property. The park had many names over the years, including Beachfront Park and Bayview Terrace Park. It was only in 2006, by a vote of 3-2, that the Manhattan Beach City Council decided to rename the park in honor of the Bruce family and to erect a commemorative plaque to their stolen accomplishments.

“Those tragic circumstances reflect the views of another time,” it read.

Far too little and far too late, considering the Bruce’s descendants would’ve easily been millionaires today had they maintained ownership of the property. Fortunately for those descendants, Kavon Ward knew that a plaque wasn’t anywhere near enough. Within her year of activism, the awareness of the Bruce’s Beach situation increased dramatically. She had Los Angeles County Supervisors and State Senators on board to make one of the most significant (and unprecedented) land returns in modern American history. By the time Governor Gavin Newsom signed over the rights to the property to the family, it was worth more than $74 million.

In an Op-Ed piece for the Los Angeles Times, Bruce descendant Anthony Bruce reflected on the opportunities now available to his family. “It will allow my family to do what countless other American families have done since our country’s founding:” he said, “inherit property and build family wealth over generations.”

There’s more to the trauma of losing land than just finances – but finally, there’s some concrete improvement to the lives of the Bruce’s descendants. It only took a century of waiting, and one year of Kavon Ward’s activism.

“Property is the one thing we (Black folks) have to ensure we have some generational wealth to pass down,” said Ward, “and white people stole that too.”

Fortunately, now she’s discovered a method of recovery.