Part One: The Biracial Question.

Above photo: a collage of the writer and her mixed family in the early 2000s.

I sat poised in my seat in front of the camera, eagerly waiting to take my college graduation photos, when the photographer readying the shot asked me the age-old question.

“What ethnicity are you?”

Usually, I receive that question in the form of “What are you?” or something equally dehumanizing – the word “ethnicity” was a step up from that, at least. I rattled off the answer with all the enthusiasm I could muster after 21 years of the same.

“My mother is Black, and my dad is white.”

The reaction I’m used to is almost cartoonish expressions of disbelief. I don’t look like their idea of a Black and white biracial American. Are they expecting a green-eyed, blonde-haired girl with caramel skin? Instead, they are met with a tan, dark-haired woman with mixed features. One who doesn’t “look” white, but doesn’t necessarily “look” Black either.

Instead of the usual denial (as if I would lie about my racial background to a stranger poking into my personal identity for the sake of assuring their own nosiness), the photographer started to wax poetic about how beautiful biracial people are. How especially interesting we look. How interesting we are to photograph. How interestingly exotic our features are in magazine spreads.

I’ve had a lot of weird things said to me about my ethnicity, but I had never been fetishized to my face.

Biraciality and fetishization go hand in hand. Today, prominent white families like the Kardashians have children with Black men; their daughters face scrutiny of their appearances at a higher rate than their white counterparts. Khloe Kardashian’s daughter, True, has faced anti-Black sentiment for her darker skin and Black features – even as an infant. If not ambiguously exotic, or white-passing, your biracial identity is the subject of endless criticism and fascination.

Facebook pages dedicated to posting photos of biracial babies and toddlers gather hundreds of thousands of likes and followers.

The comments range from fawning over the children to racist epithets. “She is ABSOLUTLEY [sic] FIERCE,” repeated one commenter under several posts of little brown girls with curly blonde hair and green eyes. “Can I have some of that beautiful hair?” asked another.

Under a different post, a commenter says “What is that?” Another adds an animated GIF of a kiss between actor Charlton Heston and a monkey scientist portrayed by Kim Hunter in the 1968 film Planet of the Apes. The implication there is clear.

While the invention of social media has allowed racist internet trolls and appearance-obsessed parents-to-be access to endless photographs of biracial children to examine and idealize, the fetishization of multiraciality has roots that run throughout the entire country.

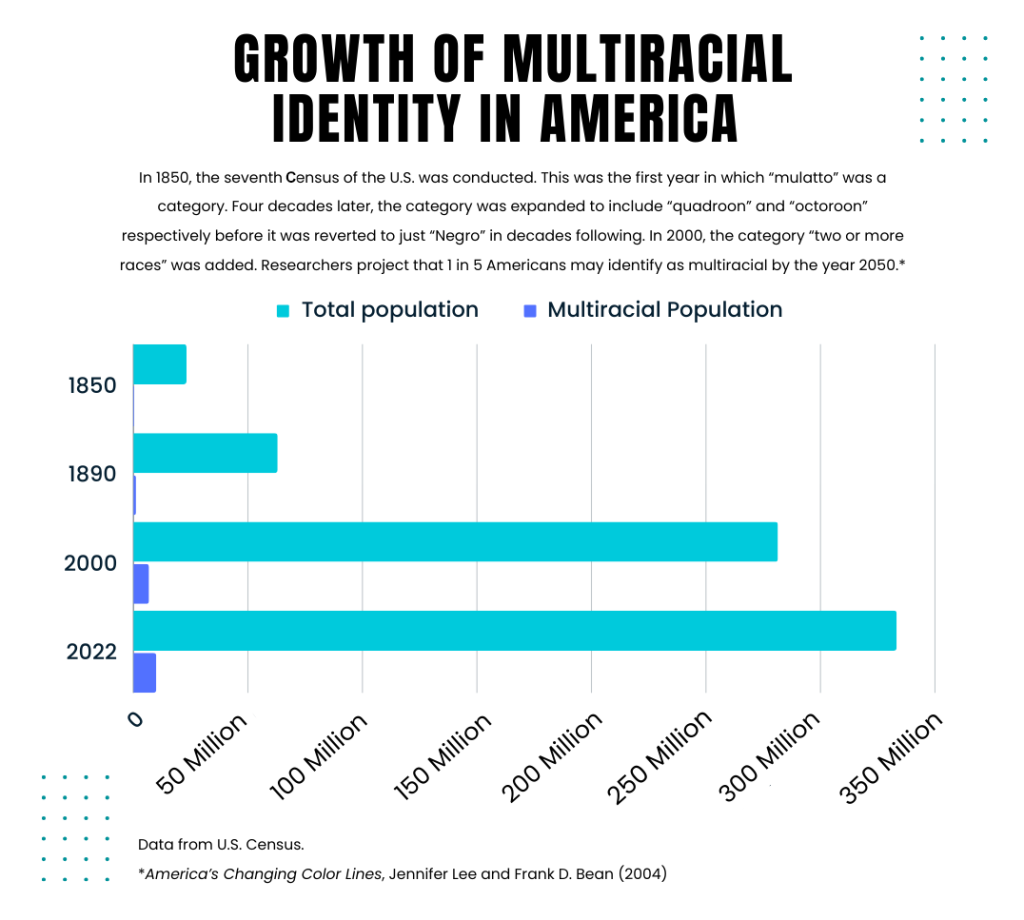

The reality is that the history of Black biraciality goes back to slavery and rape. The condition of slavery allowed for enslaved women to be systematically assaulted by white slave masters. The babies produced from these mixed race copulations were called “mulatto.” The terms quadroon and octoroon were also utilized to describe someone with more white “blood” than Black. In the year 1850, the U.S. census not only started counting Black people, but also introduced the category “M” for mulatto. A new problem emerged from this, as Census counters marked anyone mulatto who they considered “racially ambiguous,” specifically not visibly Black or white, such as Native Americans.

Many abolitionists in the antebellum South asserted the existence of biracial people was directly connected to one of the “fundamental moral issues” of slavery, according to historian Robert Brent Toplin in “Between Black and White: Attitudes Toward Southern Mulattoes.” The idea of white slave masters being tempted into infidelity and sexual promiscuity by enslaved women was the cause, they posited; thus, he wrote, if slavery were abolished, the production of “mulattos” would end.

Consequently, it did not. The population of multiracial people in America has grown by almost 9.6 million since 1850, according to U.S. Census data. As the population grew undeniably, society began to discuss biracial existence beyond the numbers.

Most of the first films and books that delved into biracial identity in women revolved around what the Jim Crow Museum describes as “personal pathologies;” the “tragic mulatto myth” perpetrated by early filmmakers and writers involved themes of extreme self-hatred and sexual promiscuity. The tragic mulatto trope revolved around typically white-passing biracial protagonists who managed to distance themselves from their Blackness at a cost.

“He said, ‘Yeah, but from where in Africa?’ And I was like, ‘I don’t know.’”

Rachel Dawson

The cost usually was despair, self-loathing and eventually having their identity discovered by their white peers. While the trope is oversaturated, grappling with cultural and ethnic identity stripped away by the shared trauma of slavery is indeed something Black and Black biracial Americans alike must deal with.

Brenda Arjona is a professor of anthropology at the University of San Francisco. According to her research, the way marginalized peoples today view their identities is tied to settler colonialism.

“[Anthropologists] pushed theories like linear evolution, saying that human beings evolved from savagery to be ‘civilized’ – civilized being white, European, male,” Arjona said. “At the same time, the colonizers used those same academic theories to say certain people are less than human, so it’s okay if we just wipe them out and take the last right. The way that that affects identity is because our identities are tied to our culture – it’s not just something that’s static. Identities are going to keep evolving, not just culturally, but individually.”

Rachel Dawson is a business student at the University of Southern California currently studying in Milan. Her father is Black, and her mother is Dutch-Indonesian. During her time traveling across Europe and Africa, Dawson said one of the biggest questions she faces is the timeless “What are you?” But just “Black” isn’t an acceptable answer.

“A lot of people don’t understand ‘African-American,’ because for them, [the idea of] slavery is not a thing like it is in the U.S,” Dawson said. “I remember one night I was talking to this guy from France and he was asking me where I was from. ‘Oh, I’m African-American, Dutch-Indonesian.’ He said, ‘Yeah, but from where in Africa?’ And I was like, ‘I don’t know.’”

In order to figure out the answer to the European version of “What are you,” Dawson used DNA testing service 23andme to ascertain her exact ethnicity. Although she discovered that her father’s side could trace their roots to Nigeria and other various African countries, it was not as satisfying a find as she’d expected.

“[My Nigerian identity] felt like a small percentage,” Dawson said. “I never grew up with it culturally, so sometimes it feels a little bit like – not like I’m faking it – but if you are told on a piece of paper that you are something and then that’s your only tie to that heritage, it’s just not the same.”

The field of Black biracial media is oversaturated with art about not knowing how to define one’s identity. Why is the “stuck between two worlds” trope so deeply entrenched in the biracial community?

Part Two: Identifying as Black American in a world that steals, yet denies, its culture.

The answer is sociological. Humans are social creatures. We all crave human connection – connection by blood, by hobbies, by race and ethnicity. Humans have an almost supernatural urge to divide, to separate, to organize ourselves into neat little boxes. But what happens when the boxes are not-so-neat? Where do we go from here?

“Blackness is multiplicitous. It’s multifarious. There are many different ways of being Black.”

Jonathan Gómez

Rachael Somers, a fourth year student majoring in philosophy, politics and economics at the University of Southern California, says their identity as a non-racially ambiguous Black biracial individual results in a discrimination beyond desirability politics.

“When I think of the discrimination that I face, I really see it as anti-Blackness rather than about my mixed identity. Being taught to value my whiteness rather than me as a person, or my Blackness,” Somers said. “The hardest part [of being Black or biracial] is the internalized anti-blackness in America in general. And I think that’s one of the privileges of being mixed, is just not necessarily really being confronted with the fact that hatred is really powerful, but internalized hatred is like a whole beast of its own. Internalization of these feelings is why systematic oppression so effective.”

Somers was able to find a stronger sense of community within her Black family, friends and peers.

“I just feel really attached to my blackness. I’m grateful for the community. My mom is incredibly Christian [..] and we went to church in Detroit. I live in Ypsilanti [Michigan],” Somers said. “Because of that, every single Sunday, I would go to my Aunt Roc’s house where my Aunt Ruth, Aunt Janice and my cousin lived. I would be there every weekend; just being close to my own family is definitely a major place where I got to learn about my culture.”

Jonathan Gómez is a professor at the University of Southern California and musicologist studying music of Black Americans as well as that of the broader African diaspora. Gómez says the question of family lineage has in many ways caused the Black American identity to become its own culture, distinct from other ethnic identities in its own right.

“Enslavement denied Black people the right to familial histories in many cases. And while there are some black people who are able to trace their families back pretty far, not everyone has that opportunity or the ability to do that,” Gómez said. “It does affect culture. Not being able to trace back [lineage] due to the destruction of the family unit [during] slavery that split up families.”

Music is one way in which Black culture first emerged as a global influence. According to Gómez, much of the music produced by the Black community is used not only to speak out politically, but to uplift and celebrate Black joy and achievement.

In the 1920s and 1930s especially, the blues emerged as a music genre; it played a critical role in painting vignettes of the black experience beyond religious spirituals, which were associated with enslavement. Jazz musicians continued this trend in the mid-20th century, with artists like Max Roach and Nina Simone composing or writing songs targeted at the political and social issues of their day. While music served as a platform for political expression, it also celebrated black joy and interpersonal connections, illustrating the many sides of the Black experience.

“Music has been a way for Black people to express political [views], but also something that gets overlooked – Black joy, and celebration, and just Black people relating to one another. While performances were political, they also could be about other things as well,” Gómez said.

Black Americans are not a monolith. Blackness is inherently anti-Essentialist; there is not a list of dress, music, dance or food necessary to indulge in to be considered “Black.” Much is decidedly shared, but the beauty of Black culture in America lies in its variance; someone in the South has cultural fixtures that are different from those of someone on the West Coast that are different from the East Coast and so on. As such, the biracial/”mixed” identity is one thread in the ever-expanding fabric of the Black American culture.

“Blackness is multiplicitous. It’s multifarious. There are many different ways of being Black,” Gómez said. “My point, and that of many other people in Black studies is not that Blackness means one thing, but that we need to take it seriously – that it does have meaning.”

Below, listen to excerpts from a conversation with Professor Jonathan Gómez on Black narratives in music.