University of Oregon student Elle Rogers gave up many cornerstones of college life – drinking alcohol or caffeine, and exercising – to donate her eggs. For three weeks in October 2018, instead of doing her usual workout routine of cardio and weight lifting, Rogers was busy injecting herself with hormones that caused mood swings, loss of appetite, fatigue and bloating.

“Once you’re taking three injections a day, it’s hard to find a spot on your belly that isn’t bruised or hurting,” Rogers said.

And these side effects were worth it for Rogers, a 5 foot 9, green-eyed, caucasian 22-year-old, who used the $7,000 she earned from her donation to fund a post-grad trip around India and Southeast Asia. “I love to travel, and I’ll do anything to get there,” Rogers said. “I was willing to do whatever it took to have the senior trip that I have always dreamed of.”

This is true for many college women who put themselves through prescreen testing, hormone injections and an egg retrieval process for cash. Once an applicant is selected as a donor by the intended parents, the physical egg donation process takes less than a month, and the payout can be tens of thousands of dollars, so young women are increasingly seeing egg donation as a quick and financially rewarding option. In fact, a study from the Journal of the American Medical Association found that the number of egg donations in the U.S. has more than doubled since 2000. In 2014, the CDC reported 20,481 donations.

The donations help intended parents who are unable to conceive themselves, such as same-sex couples and couples experiencing infertility. According to Jessica Chan, MD, a fertility specialist in the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cedars-Sinai, most of the patients seeking egg donors she sees are older couples who have gone through unsuccessful rounds of in vitro fertilization (IVF) themselves.

“Because they haven’t achieved pregnancy with their own eggs, they’ve had to have a third party to assist in reproduction,” Chan said, “but many still have an interest in carrying the baby themselves.”

Rogers’ was told her eggs went to a same-sex male couple in Israel, where gay couples recently won the right to adopt after a 2008 court decision. For her, the ongoing contention of this topic in Israel made the donation even more rewarding. “Doing this experience was huge for them, and that makes it all the more better,” she said.

Although agencies accept all fertile women ages 20 to 30, the age by which women have lost most of their eggs, the conversation is especially prevalent on college campuses. Many fertility agencies advertise their services in college newspapers and on campuses. Rogers, who donated last year, decided to donate after speaking with an agency at the University of Oregon.

“Oregon Reproductive Medicine was tabling at our school, which they do a lot actually,” Rogers said. “I found out that egg donation groups go to a lot of colleges.”

Catherine Fan, the cofounder of New Care Fertility Consulting and a six-time egg donor herself, said her agency doesn’t target college-aged students specifically. She did say that egg donation can be especially lucrative for college students because donors get paid more if they have a degree.

While desired characteristics in a donor vary depending on the wants of the intended parents, fertility services find that certain traits are more desired by buyers time and time again – and parents are willing to pay additional thousands for them. A 2012 study found that more than one-third of websites recruiting egg donors pay more for certain attributes, such as a certain race or higher education.

According to the Los Angeles Times, “supply and demand” has allowed “Asian women “to command about $10,000 to $20,000 for their eggs… [while] women of other ethnic groups typically get about $6,000.”

Fan confirms that Asian donors tend to get paid more because of their so-called supply and demand. “Asian donors are harder to find because they are more close-minded about egg donations.”

Fan also said if a donor has a higher degree, their compensation, which is taxed, also tends to be higher. From her experience at New Care, Fan said that a high school graduate will receive around $6,000, but someone with a double Ph.D will start at around $25,000. She also had one client who was Asian and had a Harvard degree got just under $60,000.

While some traits have proven more desirable among egg receivers, there are some that make an applicant ineligible to donate, such as inheritable mental and physical diseases. Rogers described a thorough prescreening process which included physical and psychological examinations and family medical and mental history checks. Through these tests, fertility agencies determine if they think the applicant is fit for donation. She said she had to share “everything” about her family history with her fertility agency, such as how her grandparents died, if her brother has ADHD and photos from each stage of her life.

Although donating eggs can have a high payout, it can also have a high physical and emotional price. In the weeks leading up to the egg retrieval, the surgery during which eggs are removed from the woman’s uterus, the donor takes hormone injections to overstimulate the ovaries. Usually, eggs die during ovulation, but the injections prevent the eggs from dropping and instead make them grow until a fertility specialist retrieves them with a tiny needle attached to a ultrasound probe. Fan said, “if you don’t give [the eggs], they will die anyway, so why not?”

Because the procedure retrieves eggs that would have otherwise been lost anyway, egg donation does not affect fertility later in life, according to Chan. She says the 10-minute procedure isn’t typically painful.

“Because she’s getting conscious sedation, she doesn’t feel any discomfort during the procedure herself – nothing sharp, nothing pokey,” Chan said. “She usually doesn’t even remember the process.”

However, there are risks such as blood clots, fluid in the lungs or abdomen and ovarian torsion, which is when the eggs get heavy and twist. According to Chan, less than 5% of donors experience a condition called ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, which can cause vomiting and weight gain.

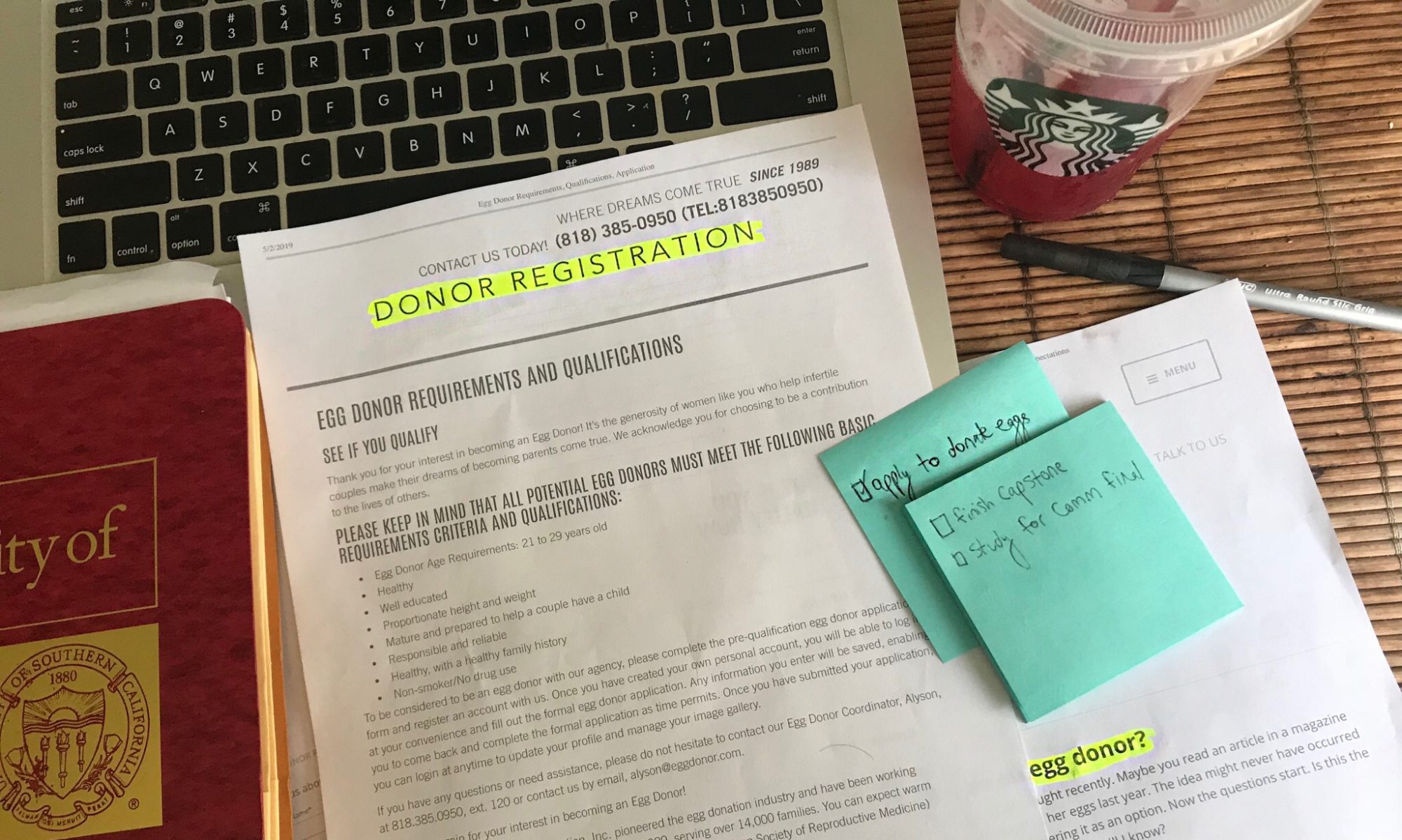

These complications are rare, and many donors are willing to take the risk. Sydney Walker, a chemistry student at the University of Southern California, applied to be an egg donor because her part-time job at Starbucks wasn’t enough to get her out of the debt she went into from buying flights to New Zealand, where she’s moving after graduation in May. Although she hasn’t yet been selected by intended parents, Walker is excited about the opportunity to get paid for helping a family.

“If another family is so willing and so invested in having a child, and I have healthy genes as far as I know at this point, I would love to be able to provide that for another family,” Walker said. “But of course, the compensation is also really great.”

While some donors, like Walker, consider helping a family to be a benefit of egg donation, some donors struggle with the idea that another family could raise their biological child. Jacqueline Baltz, a University of Southern California student, said despite the possible benefits, she would not consider donating. “I just want to know where my children are going,” she said.

However, donors undergo psychological testing prior to donation to prevent negative reactions, and research suggests that while some egg donors experience regret about donating and continuous worry about whether or not their eggs produced a child, this only occurs in a minority of donors.

“For me, I just don’t see it as [my child]; I see it as the possibility of a child that somebody else really wants,” Walker said.

Rogers agrees, saying that she’s “pretty good at desensitizing” herself from that aspect of the donation process. “It’s cool that my biology is out there, but I would always think of it as their child.”

Chan said that the donors she’s worked with have had overall positive experiences. “In general, I think most women feel pretty positive about the whole experience because they’re helping another family, helping another woman,” she said.

Rogers was content with her egg donation process and even reapplied to donate a second time. Unfortunately, she was denied from a second donation because her eggs didn’t grow as quickly as her agency wanted them to, but she has advice for other young women who are considering donating: Do it.

“First of all, do it,” she said. “It’s a tough process to go through, but you are rewarded in a great emotional sense and a financial sense. There are so many people who really want a child to love.”