I started to feel it as I was coming into the final turn of my fist lap — the familiar squishy crunch above my left heel that serves as the precursor to achilles tendonitis. I wondered how this was even possible. A quarter mile into my run, and my legs already couldn’t hang. I quickly realized that all the working out I’d done the past year had made me stronger but hadn’t improved my fitness. In fact, if it put me at risk of getting hurt, I was actually becoming even less fit. I slowed to a stop, defeated, and couldn’t help but think “What if I have to run to catch a flight… Am I going to tear my achilles or pull a muscle?” It was frustrating as I had always considered myself a good runner – I ran cross country throughout high school, and played lacrosse and baseball growing up. I’d never considered that one day I wouldn’t be able to run a short distance without pain.

I’m part of the latest wave of a trend that’s been growing in America for the last 40 years — the boom of boutique fitness. Instead of donning my headphones and hitting the YMCA, Gold’s Gym or LA Fitness, I’ve opted to join a smaller, more intimate gym and take classes led by a coach. Many of us feel we’re more productive when we work out with a timer, knowing our performance is going to be scored at the end. Many also tend to think these classes are more fun than going solo because we feel a connection with each other. All of us, for one reason or another, are willing to spend a lot more on memberships.

A typical membership to one of these gyms, whether it’s OrangeTheory, Crossfit or select yoga studios can run anywhere from $100-$300 per month. Meanwhile, a single-club membership at LA Fitness has a monthly fee of $24.99 after a one-time $99 initiation fee. Despite the considerable difference in price, boutique fitness has seen massive growth — total revenue generated from U.S. gyms went from $3 billion in the 1980s to $27 billion in 2016. That’s an increase of 450%, according to recent reports. This happened while the U.S. population grew by only 36% and GDP increased by 300%. Put simply, more Americans are spending more on fitness than we ever have.

Also on the rise is cardiovascular disease. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that the leading cause of death in America accounts for over 600,000 casualties a year, or about a quarter of annual total deaths in America. Cardiovascular disease is most commonly caused by atherosclerosis — build up of fatty plaque in the arteries that weakens the heart and leads to serious health complications. The plaque comes from poor diet and lack of exercise. And that 600,000 is only the tip of the iceberg; I can only wonder how many people develop less serious health problems or injuries from lack of exercise.

So if we’re spending more on fitness, why are we becoming less fit? This question has been stuck in my head for over a year now, when I, wanting to find a social circle outside of work colleagues and drinking buddies, decided to become more serious about exercising regularly. Every week day I was up at 5 a.m., working out by 6 a.m. Then I’d go to my classes at University of Southern California before heading to work in Venice Beach. I also started following a strict diet once I began to focus on adding size. Every day included three high-carbohydrate protein shakes, one after my morning workout, one with lunch and one before bed. Coupled with the food I was eating (tons of breakfast burritos, poke bowls and cheesesteaks) I was consuming 5,000 calories a day. Every day also included 12 grams of creatine, a popular supplement that helps the body produce more ATP — basically, if taken consistently it gives your muscles more energy.

The results came: I dropped body fat and added 30 pounds of muscle. I went from weighing 165 lbs to 200. But now I couldn’t run a quarter mile without serious pain, and I still felt at a loss if I ever attempted to explain to friends how to eat more efficiently, or how to exercise for fat loss versus building muscle. I found that few people, even among this healthy community I’d joined, had the answers.

One of the most interesting kinds of businesses riding on the coattails of the fitness industry boom is in the world of advanced fitness data. Companies offering testing from sweat rate measurements to complex blood work readings have sprouted up throughout the country, promising access to data that can help people make healthier life choices. Previously, this kind of testing was reserved for elite athletes; Gatorade’s Sport Science Institute offered testing to their sponsored athletes, as did Redbull. But more people investing in their health throughout the last four decades has created a new market for testers to sell their services to, meaning just about anyone can access data regarding their level of fitness.

I decided to use myself as a guinea pig to see if collecting this data actually helped to inform healthier life choices and get to know my body on a deeper level.

I needed to witness how finding this data could help me train more efficiently in order to reach a goal while avoiding injury. So right after I ran that quarter mile and went limping home, I signed up for the Los Angeles Marathon and began trying to run long distance.

Training for a marathon when I wasn’t able to run figured to be a challenge. I called a former running coach I’d had named Meredith Dolhare — a sponsored ultra runner whose completed some of the hardest endurance races in the world. Luckily, she was coming to LA and we agreed to grab coffee. Dolhare told me that shortly after beginning to train for 50 mile foot races and triathlons, she took tests to find her metabolic efficiency, sweat rate and sweat sodium concentration among other things in order to design a diet and training routine to help her body adjust. She also told me far more information and stories than I could ever write about, so we decided to record a podcast. Here’s a quick preview:

It was mid-November and the race was in March so I needed to move quickly. My first stop was Sparks Systems, based in Phoenix. Founded by former collegiate soccer player and coach Anna Sparks, the business offers metabolic efficiency testing coupled with continued health coaching (including design of exercise programs and nutritional guidelines) for clients tailored towards specific health goals.

Companies like Sparks aim to educate clients on how to prevent and reverse health complications caused by unhealthy lifestyles like cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes through the collection and analysis of fitness data. So I went to Phoenix, and crashed with friends. To collect my resting metabolic rate (RMR), I was outfitted with an electrocardiogram, (ECG) a small device that detects the electric current produced by your heartbeat, and a mask to measure levels of different gases in my breath. Then I sat in a chair for 15 minutes while she monitored the data in real time. My heart rate told her how hard my body was working to simply stay alive — normal brain activity and regular breathing. My breath was telling her where my body was pulling energy from: Was I burning carbohydrates or fat?

This gave me an idea of how my metabolism functioned, especially on a day when I didn’t work out. I have a high metabolism like many males in their early 20s, and when I’m in a fasted state (hours after my last meal) exactly three quarters of my energy came from fat stored in my body as opposed to carbs. This info was a great point of reference for once I collected my working metabolic rate.

Next up, a resistance bike. I maintained 60 revolutions per minute on the bike while Sparks monitored the data coming from the ECG and mask and periodically increased the resistance on the bike to make me work harder over about 20 minutes. Once I couldn’t maintain the 60 revolutions per minute, Sparks would know I’d reached the peak of my working level and it was time to look at the data.

From this test I got to see how my body reacted to certain levels of working intensity, which would let me know how hard I needed to train in order to increase my endurance and cover longer distances.

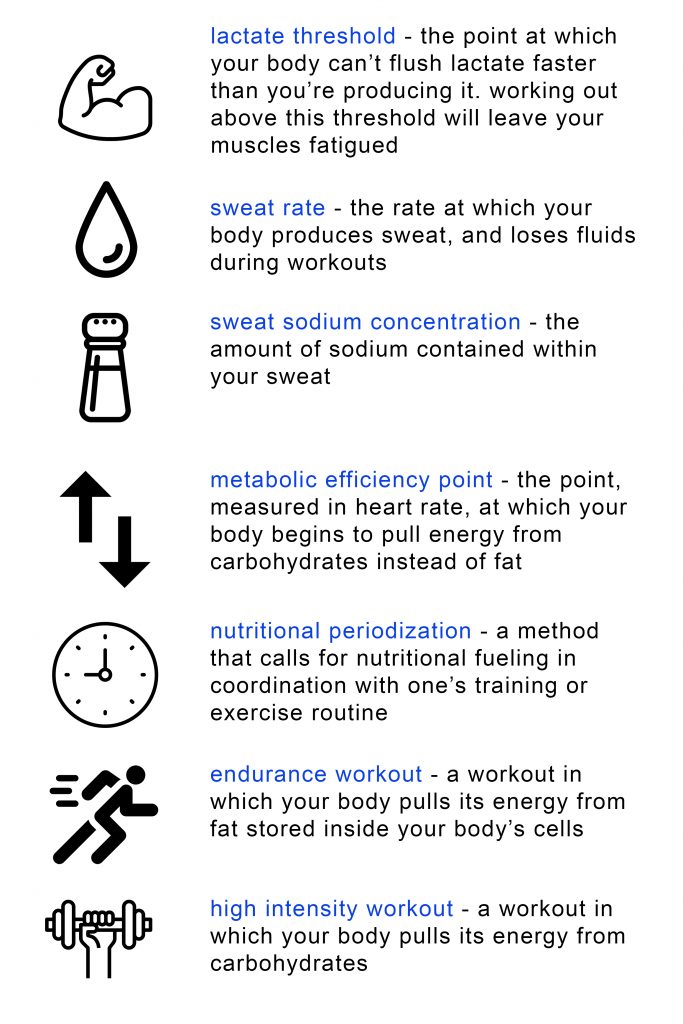

The MEP and LT were the most useful pieces of data I collected —- the MEP is a specific heart rate at which the body begins to use carbohydrates for energy as opposed to fat stored in the body’s cells. I learned that my high-intensity workouts coupled with my extreme diet had trained my body to rely almost completely on carbs – at just 115 beats per minute my body stopped using fat for energy. If I was going to run a marathon, I needed to change my workouts and diet quickly so that my body was conditioned to use fat at higher levels of work intensity.

Additionally, running above my LT (also on the lower side) would leave my muscles exhausted – meaning they’d begin to cramp up midway through the marathon and I’d be unable to finish. Running with severe leg cramps can also lead to much more serious injuries, like pulled muscles or damaged joints.

“People don’t realize they’re often overtraining and eating the opposite of what they need to in order to reach their goals” Sparks told me.

I learned that most of the effort in conditioning my body to use fat over carbs would take place in the kitchen, not the gym. Reducing the number of carbohydrates I ate daily would give my body a chance to use another source of energy. I also learned I needed to exercise below my MEP to prevent my body from using carbs while training. This meant I needed to keep my heart rate below 115 beats per minute. Over time, this combination of consuming and using less carbohydrates would push my MEP to a higher heart rate, meaning I could work harder and run faster without worrying about my body switching to carbohydrates and losing energy midway through the marathon. Collecting my metabolic data had shown me what I was doing wrong and allowed me to change my approach completely.

I didn’t stop there; I found another company, Live Well Assessments, to gather even more data on my heart’s activity. For five days and nights, I wore another ECG and kept an online diary of my activities from hour to hour, reporting everything I did.

Due to the information I received from my testing with Sparks Systems, I’d made considerable progress in my training. I’d completed several half marathons on my own, with my longest single run to that point being 16 miles. I’d dropped about 15 pounds and, though I still got sore, no longer had severe pain in my tendons. Feeling like I could handle it, I decided to go back to Arizona and run the Mesa-Phoenix marathon in February, just about a month before I was scheduled to run the LA marathon. I wore the ECG and reported my activity throughout the weekend.

The results show how my heart behaved on the day of the marathon. The blue periods reflect exercise that improved my aerobic fitness, the red being periods of stress and the green being time that my body actually reached a rested state for long enough to recover from the activities of the day. The rested state is reached when the body’s activity becomes controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system, which conserves energy and allows the body to expend more nutrients on repairing damage done to muscles throughout the course of a workout. Reaching the rested state is paramount for anyone looking to improve fitness throughout a training regimen; failing to properly recover from training sessions means you’re at risk of working yourself into injury or illness, and not benefitting from the training at all.

My body barely recovered throughout the day even though I was engaging in routine activities such as driving and eating. What I should have done is take a quick ice bath to reduce inflammation, then get in bed for a few hours. What I actually did was go to lunch with friends, then spend a few hours in the hot tub right before I cracked open a few beers and went to several bars to celebrate finishing the race. Drinking significantly inhibits the body’s ability to reach a state of recovery. So even though I went to bed around 1 a.m., I only got a blip of recovery time just after 8 a.m. the next morning.

“What’s more important than the number of beats per minute,” explains Live Well Assessment’s Patrick Khoo, “is heart rate variability. In other words, how consistently is your heart beating, and how long does it take for your heart to return to a normal resting heartbeat following exercise. This tells us how intensely you were working during exercise and more importantly, how efficiently your body can recover and prepare for the next training session.”

This is exactly the kind of data that informs healthy decisions. Because of what I learned from this test, I was able to recover more efficiently throughout the remainder of my training by making more informed decisions about when and how hard I exercised, how often I did, and what I ate, drank and did throughout the day.

The positive effects took place much more quickly than I would have thought. Just a few more weeks of training below my MEP and eating a reduced number of carbs allowed me to train harder without my legs experiencing pain. Adding in a revised approach to recovery in between training sessions helped me get more out of every run. Without having access to any of this data, I never would have made that progress. I would have continued to overeat carbs, overtrain my body, and make choices that drastically inhibited my ability to recover. Opting into the testing allowed me to visualize how I needed to improve my eating and training habits.

In the early hours of March 24, I lined up outside Dodger Stadium with close to 30,000 other runners preparing to run LA Marathon. The famous “Stadium to the Sea” route had us take Sunset Boulevard through West Hollywood, then head south and take Santa Monica Boulevard to Sepulveda. We briefly turned north before taking San Vicente from Brentwood all the way to Ocean Avenue in Santa Monica, where we crossed the finish line.

I’d be lying if I said I breezed through it – I finished in 4 hours, 37 minutes – but I wasn’t one of the runners whose legs locked up with severe cramps somewhere between miles 12 and 18, either. Most importantly, following the race I got my hands on some ice, drank nothing but water, and quickly got to bed. I’d gone from a quarter mile jog with severe pain to a 26.2 mile race injury-free within a matter of months, and I wasn’t going to let a few beers mess with my much-needed recovery from it all.

What this all has proven to me is that anyone – elite athletes to the average joe and everyone in between – can improve their heath by using data to get to know their body on a deeper level. It’s invaluable to know your current level of fitness according to your own heart, and to recognize how your lifestyle may be affecting your fitness in negative ways. Whether you’re overtraining, eating poorly or have lost motivation to exercise altogether, visualizing where and how you’re going wrong is a huge step in the right direction. And we’re part of the first generation of human beings who are capable of accessing this data – and that by itself is pretty cool, right?

Check out the fitsense podcast to hear in-depth conversations with the experts I met while training for the LA Marathon (available wherever you listen to podcasts).

Stuart Gill is a Los Angeles-based writer and producer of sports media. To contact Stuart and view more of his projects, head to his website https://stuartlgill.com/