KATHERINE WILES

LA WAS SLAMMED BY STORM AFTER STORM THIS YEAR. WHERE DID THE WATER GO?

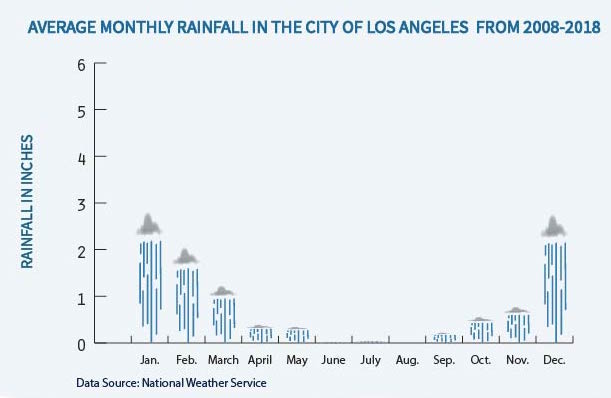

A mere trickle of slimy-looking water at the bottom of the Los Angeles River is not an uncommon sight in the middle of the region’s average “rain season,” which stretches from October to April in Southern California.

Algae grows on the stagnant water, which is some shade of brown, and an unpleasant stench wafts off the river’s surface.

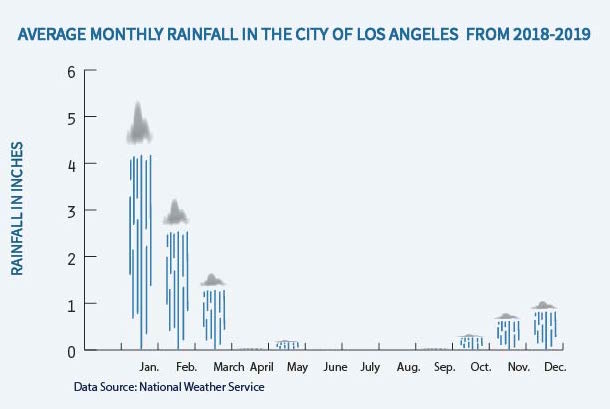

But for the first time in years, Los Angeles residents saw water rushing down the typically bone-dry concrete. An estimated 18 trillion gallons were dumped on the city throughout the 2018-2019 season by seemingly uncharacteristic storms and an atmospheric river. The LA River flowed once more.

And as it flowed, people started to wonder where all that rainwater was going.

“We’re very fortunate this year in that we got so much of it. But it’s kind of made a lot of people realize, ‘Oh, we’re not doing anything with this water, and that’s really dumb,’” said Devon Lukasiewicz, who works for TreePeople, an environmental nonprofit advocating for sustainable development and environmental awareness. “It was really dumb.”

TreePeople has been pushing for more responsible water usage for years, most recently backing a measure that raises money for increasing stormwater capture in Los Angeles County. The nonprofit has a massive cistern at their campus in Coldwater Canyon Park. The underground unit has a capacity of 216,000 gallons, and it’s been full practically the whole winter. The water collected is used to maintain the park during dry seasons and droughts.

Lukasiewicz noted that sustainable water management is important because with climate change already taking place, water will only continue to become more scarce.

“If we had a better method of collecting that rainwater … then we’d have a much better shot in the future as a sustainable city, because we’re going to need it,” she said.

“It’s our duty as a city to be on top of that and be ready, and to fight for sustainability and a future for everyone, because if not, we’re screwed,” Lukasiewicz added.

The city seems to be on the same page. LA Mayor Eric Garcetti has made sustainability a priority of the city through the Sustainable City pLAn, announcing an even more aggressive proposal in late April. The city will have the capacity to capture 150,000 acre-feet per year by 2035, and 70% of all water will be sourced locally, compared to only 15% between 2013 and 2014.

A crucial component to the plan is the extension of spreading grounds, a flat area of land that is positioned to collect large amounts of rainwater. The land has a few feet of gravel and sand layers, which the water percolates through. The naturally purified water collects in a groundwater aquifer, which is like a large underground lake.

The Watershed Management Group, a division of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, has been working to improve and expand spreading grounds in the region. As of February, the capture capacity had already increased by 10,000 AFY.

However, the systems were not able to capture a large amount of the rainfall LA saw this season. As the Los Angeles Times wrote in an eye-catching headline, most of that rainwater “simply goes down the drain.” It’s not that simple.

“All we really have to do is infiltrate that water down into the aquifer and that can be a viable source for us infinitely.”

Art Castro, Manager of Watershed Management LADWP Water Resources Division

“Our stormwater capture infrastructure is built on historical patterns,” said Art Castro, the manager of Watershed Management LADWP Water Resources Division. “Storms would come in slowly — not intense — so the ground would have time to capture, infiltrate, and be ready for the next storm in a week.”

Because this winter’s rainfall was more intense and more often than usual, the soil at the spreading grounds was too saturated to absorb a trillions-of-gallons deluge.

“When it gets saturated, there’s no room for it to infiltrate and it just runs off onto the street and down to the LA River and down to the Pacific Ocean,” Castro said.

The county owns nearly 30 spreading grounds, which are operated by the Flood Control District. The district was instituted in 1915 after major floods with the mission to protect life and property, as well as to improve water conservation.

Eric Batman, a senior civil engineer in the water resources division of LADPW, explained that while his department is interested in collecting rainwater whenever possible, if the spreading grounds reach capacity, they have to send remaining water down the storm drains and to the ocean to prevent flooding.

Spreading grounds help to recharge the groundwater aquifer, which provides potable water. It’s also less expensive to use more groundwater because LADWP already owns the water rights. The treatment facilities are already built, as is the pumping and distribution infrastructure.

“All we really have to do is infiltrate that water down into the aquifer and that can be a viable source for us infinitely,” Castro said.

Becoming more self-reliant in terms of water supply is important for Southern California cities. According to Kelly T. Sanders, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at USC and an expert in water management, “Ninety percent of all the water that enters Los Angeles comes from far, far away.”

That water comes from three main sources: the State Water Project, the Colorado River Aqueduct and the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Each of these pipelines is over hundreds of miles long, and only the Los Angeles Aqueduct is gravity-fed. That means that the other two pipelines require large amounts of energy to pump the water, which carries other environmental implications, Sanders said.

“Our water doesn’t come from here, which is dumb because we get trillions of gallons of water from rain that just goes right into the ocean with all this trash and oil and debris. Which sucks. It poisons our ocean,” TreePeople’s Lukasiewicz said.

TreePeople educates residents on how to capture rainwater in their own backyards.

“We take water for granted, and it’s time for us to stop doing that, because without it, we’re in trouble.”

Devon Lukasiewicz , TreePeople

That’s what George Nune has been doing since moving into his Highland Park house in 2015.

Four 50-gallon barrels in a collection system are lined up against the back wall of the house, connected to a gutter that runs down from the roof. They typically filled once or twice during winter months, but have been at capacity this entire winter as the city received nearly 18 inches of rainfall.

“The water gets a little frothy sometimes, which makes me wonder whether it has — you know it’s washing whatever is in the air and on the roof,” Nune said. “I wonder a little bit about the quality of water, but it seems to be OK.”

He uses it mostly for watering his garden.

Though Nune didn’t install the barrels on his house, he said he would be interested in a more extensive system now. If he decided to get more rain barrels, he could get a rebate through LADWP. Rebates are offered on 50-gallon barrels, as well as cisterns of all capacities.

BlueBarrel sells recycled barrels from the food industry to be used as rain barrels. The company supplies barrels all across the country. The company’s founder Jess Savou said that most of BlueBarrel’s customers stick to the two-barrel system, but the largest system one of their customers ever installed was 44 barrels.

“The truth is rainwater harvesting is an environmental benefit. It helps stabilize stream levels and base levels and waterways,” Savou said.

BlueBarrel used to have more customers in LA during the drought, but the number has since declined.

These efforts are just a small piece of sustainable water management. As Lukasiewicz explained, a sustainable future is critical, and water management is a key component of that.

“Without sustainable water infrastructure, we don’t have a future down the line. And that’s something we take for granted,” she said. “We take water for granted, and it’s time for us to stop doing that, because without it, we’re in trouble.”