Every Weekend, Of Every Month, Of Every Year

They gather before sunrise at Pan Pacific Park for their typical weekend activity: three to four games of pickup basketball. The February winter weather has been deterring the casuals lately, but the group can still count on its regulars to arrive.

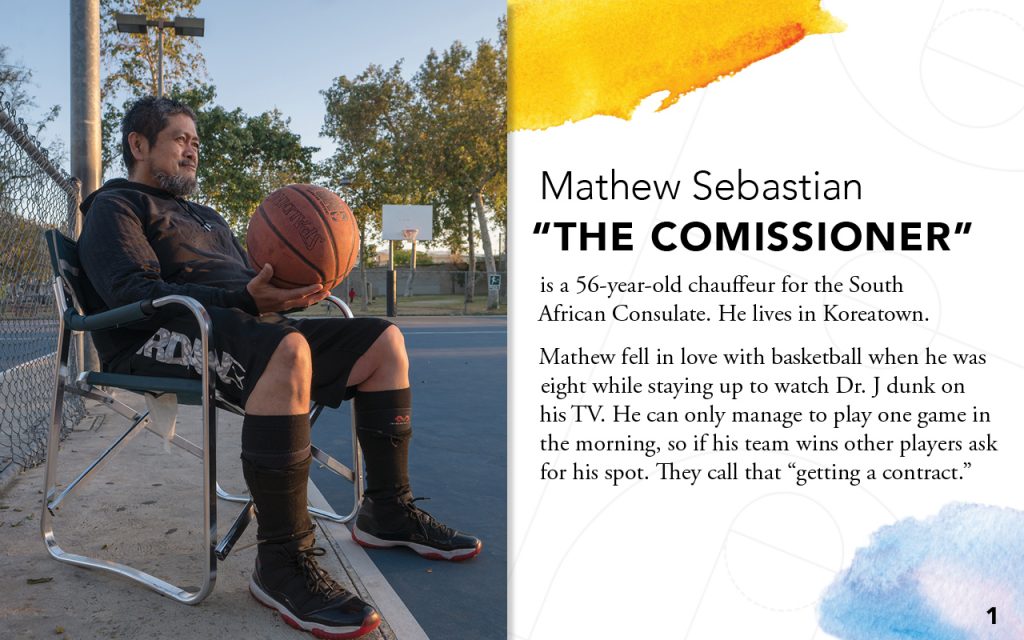

One of the first is “The Commissioner.” Waking up at 4 a.m., an hour earlier than his weekday job, is automatic to him.

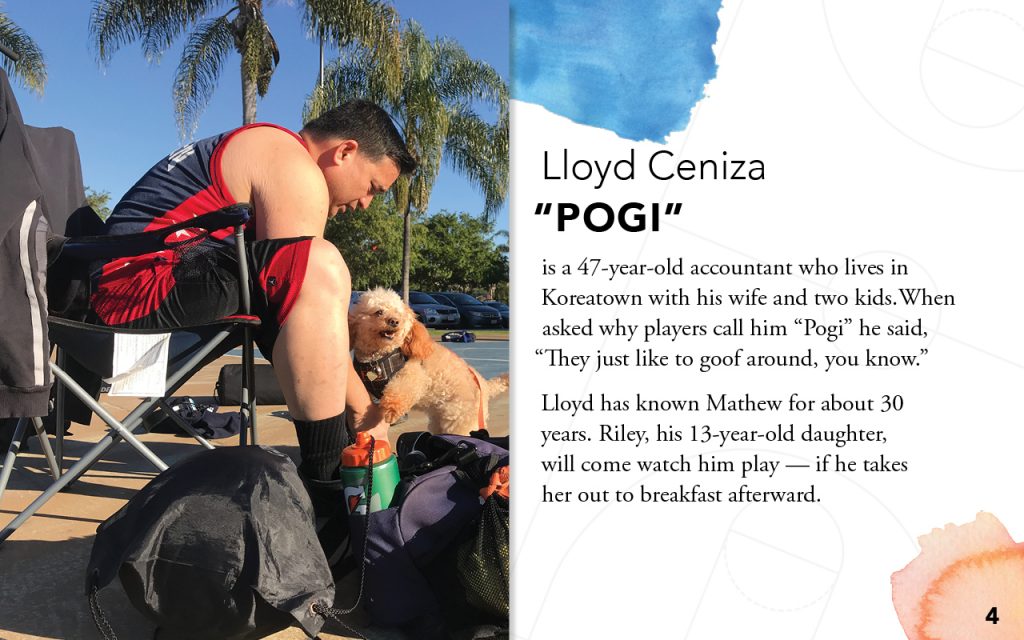

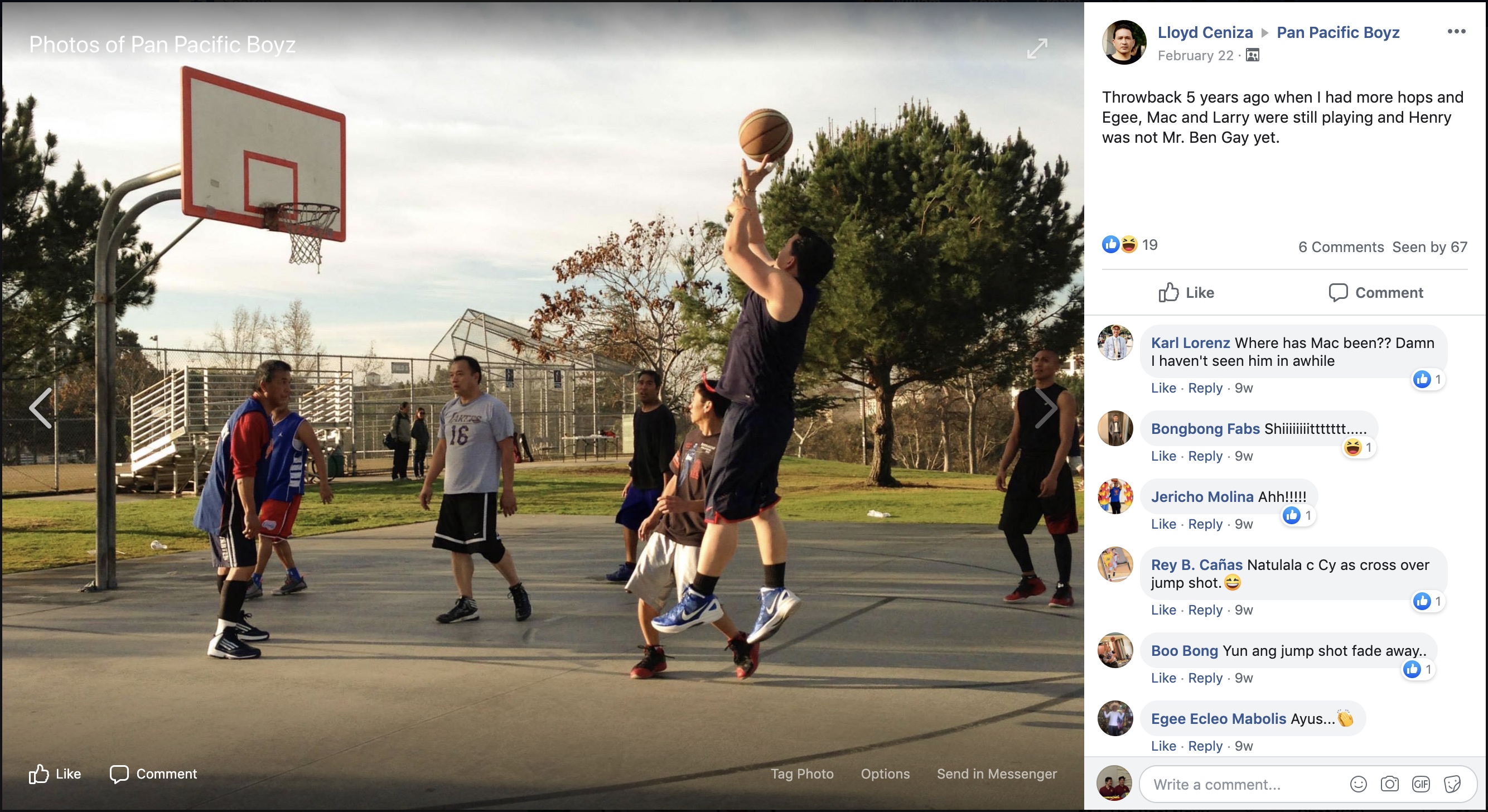

“You’ll see the typical 10 people that show up here at 4:30 a.m. in the morning. They’ll never miss a weekend…There’s die hard guys,” said Lloyd Ceniza, who the players unofficially call “pogi”, “pretty boy” in Tagalog.

After more than a decade, everyone knows the routine like clockwork. As soon as each member arrives, he puts his name down on a signup sheet. Games here are first come, first served. Tip off is at 7 a.m., promptly after the sun rises, and the last game ends at 9 a.m., just as the local park-goers trickle in.

For two hours, players hysterically shout at each other in Tagalog. Some coordinate plays on the fly by calling their teammates’ nicknames. The more competitive players berate each other: “I was open!”, “Why you hotdogging?”. “Kobe” is the most vocal. With his Kobe Bryant gear and a fiercely competitive drive to match, he’ll nag you if you’re not making your shots. “Jordan”, also known for wearing his namesake’s athletic clothing line, is ironically less driven. He prefers to goof around, playfully wagging his tongue while he shoots on the inside and drives layups.

At 8:40 a.m., players congregate on the sidelines in foldable camping chairs while watching the last match unfold. Pogi and another man hold toy poodles on their laps. One disappointedly recounts his loss in the tournament they had a week ago. Two passionately argue over Rodrigo Duterte — one for, the other against. Some discuss Filipino politics, while others are purely there to make jokes and talk smack. But everyone is reveling in the lively atmosphere they’ve created.

The conversations had on these sidelines, about anything from politics, to health, to women, are just as important as who won or who lost that morning. They form a familiarity among the men, even family.

This one calls themselves “The Pan Pacific Boyz.”

More Than Just A Hoop And Some Concrete

The Boyz drive to the Fairfax District from neighborhoods across L.A. to play — from Koreatown and Echo Park and as far as Burbank. A public court momentarily bridges their spatial divides.

“Lots of racial and ethnic groups look for and embrace and revel in those opportunities to be together with one another.”

Michael DeLand

Members typically hang out at each other’s homes to drink, eat, and watch an NBA game or a boxing match. Per tradition, they hold biannual summer and winter tournaments in the indoor gym, followed by a massive outdoor picnic. Last week’s tournament hosted 14 five-man teams, 70 players total. Each pitched in $30 to have someone buy meat and fish to marinate and grill at the park. One orders the lechon, or whole roast pig, and another brings the massive pot of rice. Everyone lines up buffet-style to fill up their plates, eat and socialize under the shade in the foldable camping chairs.

Some dads even bring their sons, high school basketball players, to the court. If a dad is working that morning, his son will even bum a ride from someone else and play without him.

“They like hanging out with folks that’s their dad’s age, but you know, we all get along,” Pogi said.

Catch up with any events you might have missed on the “Pan Pacific Boyz” Facebook group, created two years ago, where they share photos, make more jokes and talk more smack, just like they do on the court. One member, Karl Lorenz, is a photographer. He shares photos from recent games and tournaments.

Being around other Filipino men allows players like Pogi, who moved to Koreatown from the Philippines when he was 12, to reconnect with their homeland.

“My Tagalog has gotten better hanging out with these guys,” Pogi said. “My grammar is OK, but you know, I try and I think they respect that.”

Some buy the Filipino channels on cable to stay updated with current events in politics and entertainment and discuss them on the sidelines that following weekend.

“If your local park is populated by people who are racially or ethnically similar to you, then what you’ll find is that this becomes a place of embracing or enhancing your solidarity to that group,” said Michael DeLand, a professor of sociology and criminology at Gonzaga University. “Lots of racial and ethnic groups look for and embrace and revel in those opportunities to be together with one another.”

Their Camaraderie Is Unique, Especially in L.A.

It’s an archipelago of what DeLand has called more than a hundred “cultural islands,” isolated from one another by a concrete sea of interconnected freeways and streets.

Although the city is diverse as a whole, decades of racist housing policies designed to bar people of color from securing housing have created powerful socioeconomic boundaries that remain to this day.

“Los Angeles is quite dispersed, so for people to bond through sports and games can be quite hard,” said Ben Carrington, a professor of sociology and journalism at the University of Southern California.

L.A. lacks a discernible center, unlike its fellow world cities. In New York there’s Manhattan, London the West End, and Tokyo, a central area comprised of five wards. It’s an archipelago of what DeLand has called more than a hundred “cultural islands,” isolated from one another by a concrete sea of interconnected freeways and streets.

On each of these islands, you can find one or two public courts that “reflect something about the character of life in the surrounding area,” according to DeLand. In South L.A. you’re more likely to find courts with players that are predominantly African American. In East LA they are Latino, and in Brentwood, white.

Courts transcend these biographical barriers. They become a converging point where men with diverse backstories engage in intense, emotional interactions with one another, according to experts who study the sociology of sport. This particular group’s existence was entirely built around Pan Pacific Park; the evidence is in their name.

Before The Men Became “Boyz”

The Commissioner and Pogi, 56 and 47, are some of the Pan Pacific Boyz’ longest-attending members. When they met in the mid-to-late eighties, they shared little else in common but the courts they frequented and their lifelong devotion to basketball. Now, they’ve spent more than 15 years playing here, a vibrant and grassy park nestled in the heart of a residential area adjacent to The Grove.

When Lloyd started playing at Pan Pacific Park in 2000, there were already a small group of regulars — some whom he had recognized from 10 years ago at Silverlake, including Mathew.

In 1979, long before Mathew was The Commissioner, he was a 16-year-old boy who had just immigrated from the Philippines to the U.S. with his older brother. Mathew had just graduated high school. L.A. was an unfamiliar place and he missed his friends back home. Five years later, 12-year-old Lloyd moved from the Philippines to Koreatown — not far from Mathew — where he went to Berrendo Junior High School for a year. Every day during the summer, he’d climb or crawl through a hole in his school’s fence to play basketball with his friends.

When Mathew moved to the U.S., he had stopped playing for six years because he didn’t have friends to play with. “Back then it was adjusting time,” he said.

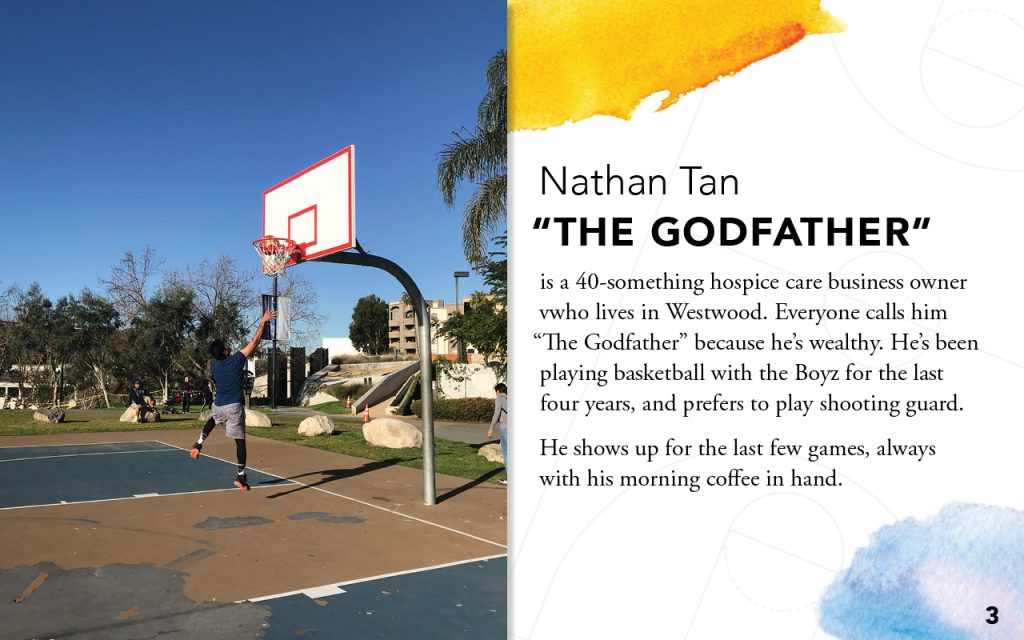

In 1985, a couple newfound friends invited Mathew, now 25, to finally play again at Belmont High School. By that time, Lloyd was already seasoned. He was a Reseda High School varsity team guard who was always looking for a game. Throughout the mid-to-late eighties they hit the same courts, occasionally crossing paths at Virgil Junior High School, Bellevue Park and Silverlake Park, yet they never got to know each other.

When Lloyd first started playing at Pan Pacific Park in 2000, there were already a core group of regulars, the original members — some of whom he had recognized from 10 years ago at Silverlake, including Mathew.

“I don’t remember exactly who told me about this park or if I passed by and just decided to pull in,” he said.

From that point on, The Pan Pacific Boyz grew by word of mouth. A current member invites his friend or family member to join, who stays and invite someone else, and so on. Those members become the new group, and over time, “[it] grows and recycles itself,” according to Pogi.

Unlike league games, there’s no referee in pickup. The game is commissioned by and for the players. They call their own fouls, keep their own scores, and settle their own arguments. At Pan Pacific Park, that’s done by taking a shot at the three-point line. Say Kobe calls a foul on you, and you barely touched him. “Hey, the ball went out of bounds off your foot!” What? No it didn’t.

“We’ll just say shoot for it,” Pogi said. “Ball don’t lie.”

Through having a say in the rules, players create their own significance from the game, making them meaningful and not just “mere play”, wrote DeLand. “The arguments, the imposing of rules is part of the fun, is part of what it means to be together in that setting.”

As Pogi got older, he found it was stressful and tiring having to argue with new people every time he played. There was no consistency. Every spot had different rules, different kinds of players and ultimately, a different feel at different times of the day. He’d show up not knowing whether there’d be people there in the first place, and whether those people were his same age and skill level.

“In some ways playing with strangers is hard. It’s hard work to create a new team together, a new dynamic,” DeLand said. “As folks get older…[they] find a kind of ease or a rhythm at a specific site where they can anticipate that at least a majority of other people who are going there to play know something about them.”

That’s why Pogi likes to learn everybody’s name so he can call on them during games. He believes that when there’s an established camaraderie, players work better together as a team.

Until Next Weekend

It’s pretty easy when, for two hours on a Saturday and Sunday morning, there’s a rhyme and rhythm to the routine that unfolds.

The Commissioner calls the shots. He customarily divides players into teams by height, skill, and age to make games more competitive — that is if Kobe doesn’t intervene. He might not admit that he tries to create “super teams” by handpicking the best guys.

Courtesy of Karl Lorenz.

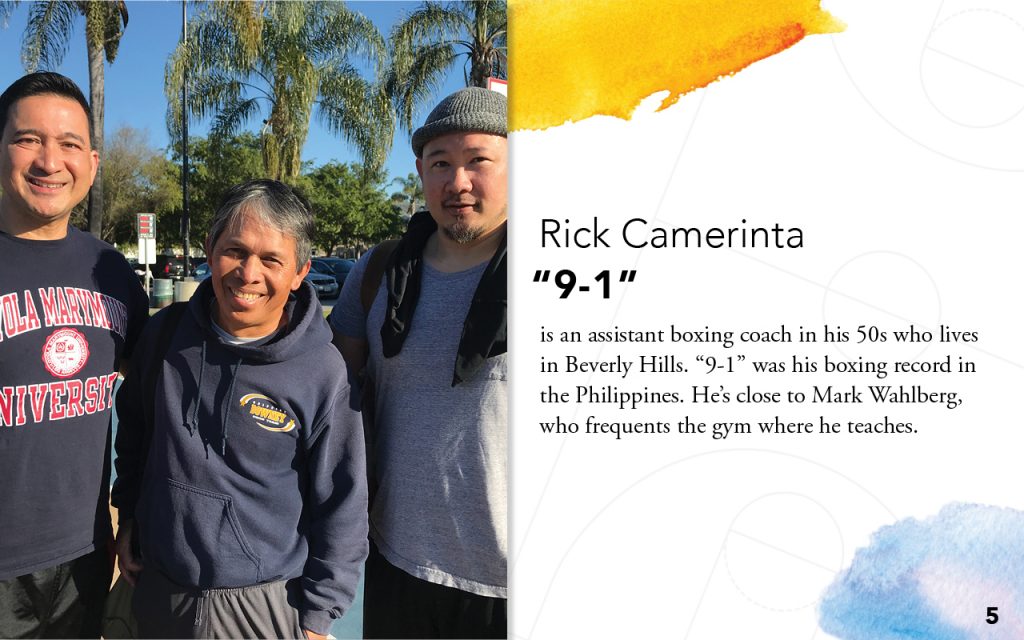

It’s 7 a.m. and the shouting has begun once more. Pogi’s 13-year-old daughter Riley takes videos of her dad from the sidelines. The Commissioner shuffles up and down the court. Jordan is at it again with his tongue. As if on cue, “The Godfather” shows up in his white Porsche at 8 a.m., just in time to play the last couple games. He’s a wealthy hospice care business owner who fronted the $600 needed to rent the indoor gym for the last Pan Pacific Boyz tournament. If you ask him yourself, he acts modest: “I handled the finances.”

By 9 a.m. most players have cleared the court. Some walk their dogs, come back with their families, or simply return home. Pogi unties his toy poodle Scout’s leash and takes Riley to breakfast. New park-goers breathe life into the park once more. Toddlers storm the playground with their mothers frantically in tow. A few African American kids from Fairfax take turns shooting at the hoop.

And the Pan Pacific Boyz resume their daily lives…until next weekend.