Last December, in a brutal crackdown against student protests in Iran — what became the deadliest political unrest since the Islamic Revolution 40 years ago — over 1,000 student protesters were killed when they took to the streets to protest rising oil prices. One of them was the cousin of Artem Anvar, an Iranian-American activist with the National Union for Democracy in Iran based in Washington D.C.

“I don’t think anyone can understand how much you can hate a government until they take away something you can never replace,” Anvar (27) says bluntly.

The government Anwar is speaking of is the Islamic Republic of Iran. And what that government took from him, he says, far exceeded the freedom and opportunity that it has been taking from Iranian citizens since the regime rose to power.

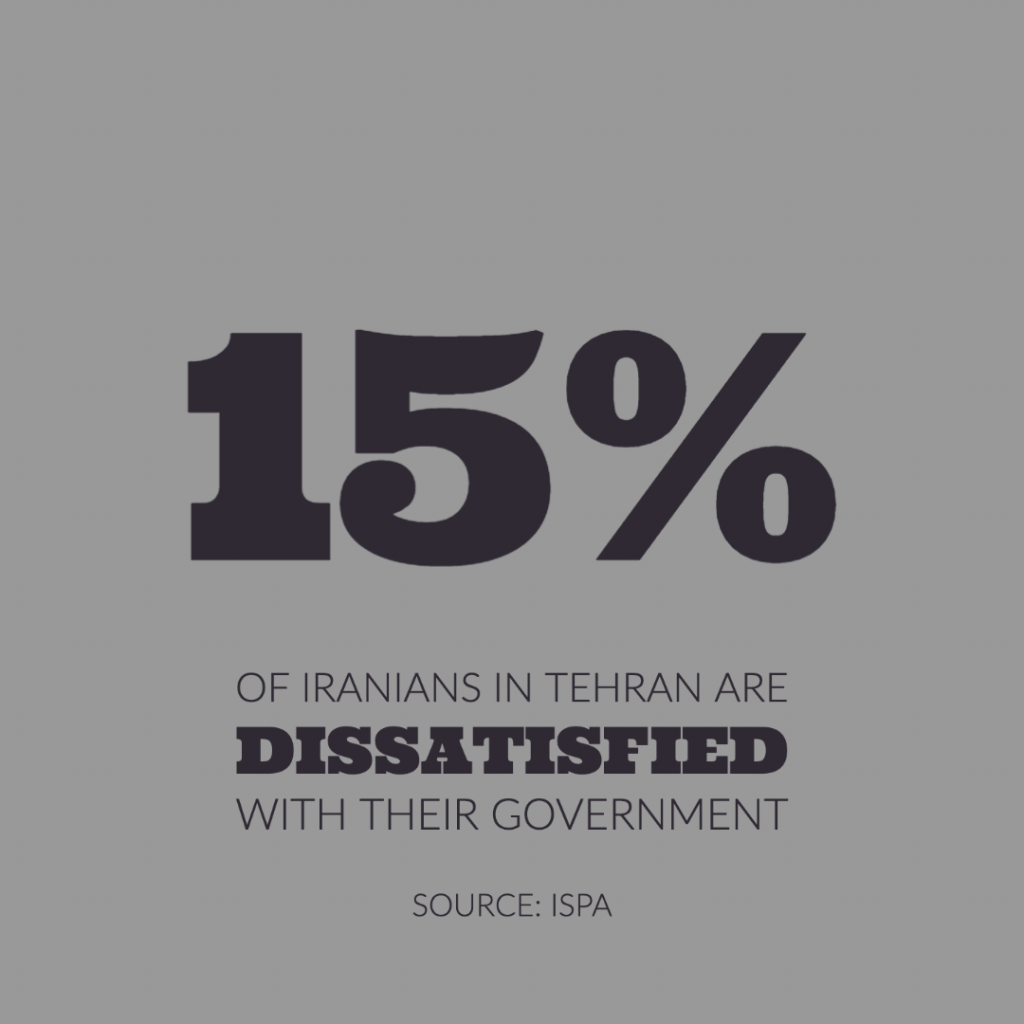

Although Anwar speaks with strong emotion, he is not dramatizing any sentiment that many Iranians have not shared. According to a poll conducted by the state-run Iran Students Polling Agency (ISPA), just 15 percent of the people in Tehran are satisfied with the Islamic Republic’s performance in the country.

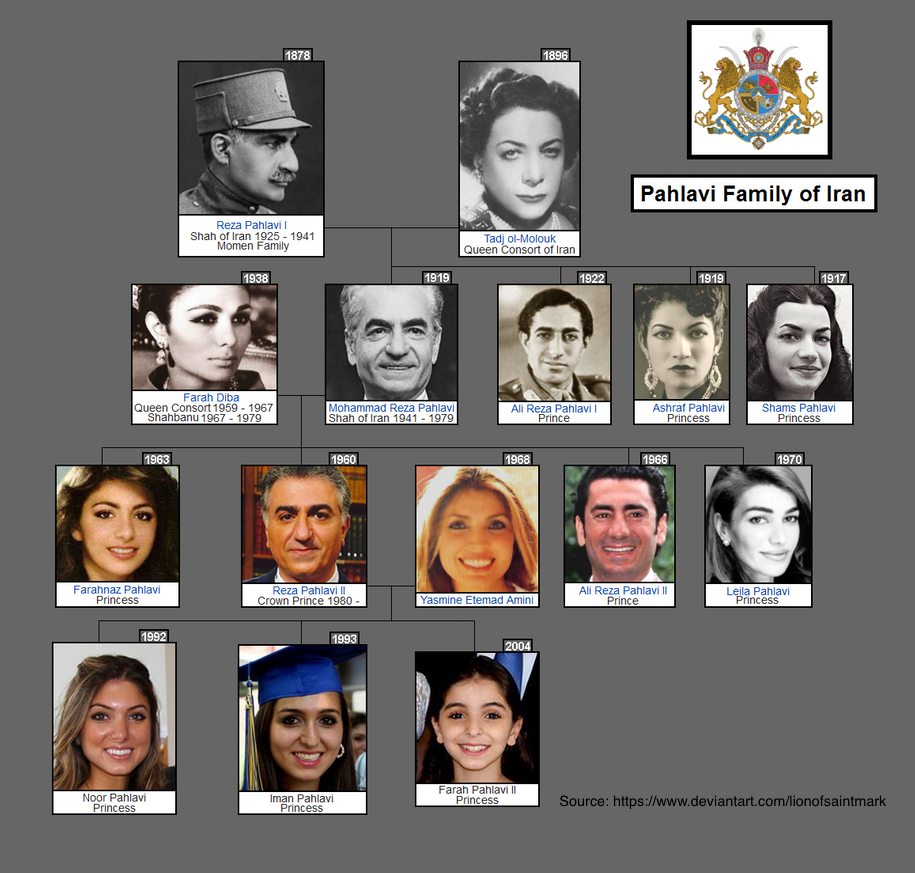

As a result, Anvar has joined a movement along with thousands of others to dive deep into their roots —their parents roots —with the National Union for Democracy in Iran (NUFDI) a nonprofit committed to fighting for a free, democratic Iran by promoting the stories and struggles of Iranian citizens to western audiences. And they are doing so by recognizing Prince Reza Pahlavi, the shah’s eldest son, as a symbol of national unity.

Prince Reza Pahlavi is the heir of the Imperial State of Iran, the crowned prince of a monarchy that has been exiled since the 1979 Revolution. Many Iranians who fled Iran after the Revolution recognize the Pahlavi family as the true symbol of Iran, and this organization links the nostalgic sentiment with policy to work its way into Washington.

“We are working with political leaders, the White house, and the media to share the Iranian people’s voices to promote the idea that Iranians want a free state,” NUFDI Director of Publicity and Press Cameron Khansarinia says. “They want to go back to the rights they had with the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.”

If there was any kind of checklist of an effective organization, NUFDI may have won the jackpot. While combining an extensive network of professors, lawyers, politicians, and activists to create a coalition with strong connections in politics, its leaders are using an emotional appeal to do so.

If you ask anyone about the era of the Shah, many will emphasize the notion of the good old days. My mother’s eyes instantly well up every time she speaks of how much she loved the Shah growing up.

“The family was just so classy,” my mother recalls, with a tint of sadness in her voice. “They were the true symbol of Persian culture and we were proud to be citizens of Iran. We were allowed to do whatever we wanted. The women didn’t have to cover themselves unless they wanted to.”

The pro-West Pahlavi family, with their once massive and beautiful palaces, exotic clothing and jewelry, and elaborate architecture, were what made them a symbol of the Iranian dream. It also became the reason for their demise. While the family lived lavishly, and the country did seem to be doing well economically, many grew wary of the Pahlavi’s exuberant lifestyle and wondered if Iran’s vast oil supply was actually being invested in the country.

And as it turned out, the Pahlavi family was taking money from their resource-rich country to fund their luxurious life, at the expense of the Iranian citizens. Anyone who spoke out was jailed and it became illegal to say or do anything that opposed the government. There became a paradox between what the citizens loved most about their rulers, and what they hated most about their rulers.

“The Shah’s regime was very corrupt,” says USC Professor of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science Muhammad Sahimi, who left Iran just before the country exiled the Shah.. “We had social freedom, sure. But no one could speak up about anything that was going on.”

So, why is the sudden interest in the revival of the Shah growing in popularity? His Twitter account alone has nearly 400,000 followers and continues to grow everyday, having activists and celebrities alike reposting and sharing his message.

Assal Rad, a research fellow at the National Iranian American Council who has a PhD in Middle Eastern History with an emphasis on national identity formation and identity in post-revolutionary Iran, claims that the idea of Prince Reza Pahlavi as a popular political figure is much more pronounced in the diaspora than it is within Iran itself.

“Growing up, I had this idea of what being Iranian meant– the history, politics, language. When I went to Iran, I found out these were very different realities…The idea of monarchy and the Pahlavi family is a nostalgia of the past in people that are no longer part of that country and have not watched it evolve,” Rad says.

Rad explains that the notion of the Shah revival exists primarily within Iranians who fled the country after the Revolution, or in the first generation of Iranian-Americans who hear stories from their parents about the glorious past.

It’s hard to tell what is reality. Has the country really “evolved” as Rad claims? Are Iranians really just clinging on to an idea?

On one hand, as an Iranian-American myself, I fall prey to listening to stories of a gilded past, sitting wide-eyed and in awe as my parents describe their days in the beach towns of Iran, the highly efficient educational institutions, and the flourishing economy of their childhood days. Yet I always sit equally as wide-eyed when my father tells me of the horrors that fell over the country after the exile of the Shah and the introduction of the Islamic Republic. Or the civil unrest beforehand, when his town got burned down and he and his family had to flee everything they had ever known.

Iranians are no stranger to protests and mass demonstrations. In fact, that is precisely how they ended up in this situation to begin with. Yet, there is no denying that despite the downward spiral that resulted after protests that led the Shah to flee Iran, the protests now are faced with a different kind of fate.

My own father took part in protests against the Shah’s corruption in the late 1970s. “We were mostly students, we thought we knew everything,” he told me. “We wanted to be like America and have political freedom, so we protested for the Shah to leave. But after everything that happened, I wish we never did. Anything would have been better than this.”

NUFDI, the organization Iranian-Americans like Anwar are committed to, utilizes the ideology of Shah revivalism to push its anti-Islamic Republic agenda. In light of the current rising tensions of unrest in Iran, this is a useful tactic and when analyzed, shows that this nostalgia is in fact quite common.

Perhaps, in a way that Americans gravitate towards the notion of “Make America Great Again,” Iranians seek desperately to make Iran Great Again, and cling to certain sentiments that may have never truly existed, just to escape their current situation.