As Lauren Milstein combs her fingers through her ribboned-curled hair, her hand stops, head tilts to the right, and forehead creases wrinkle like crumpled foil as she pauses to recall a strange fact about herself: she never saw her great-grandmother’s feet.

“She always wore flats,” the 20-year-old said of her great-grandmother, Thelma Zimmett. “I never saw her feet. Actually, I never saw her toes.”

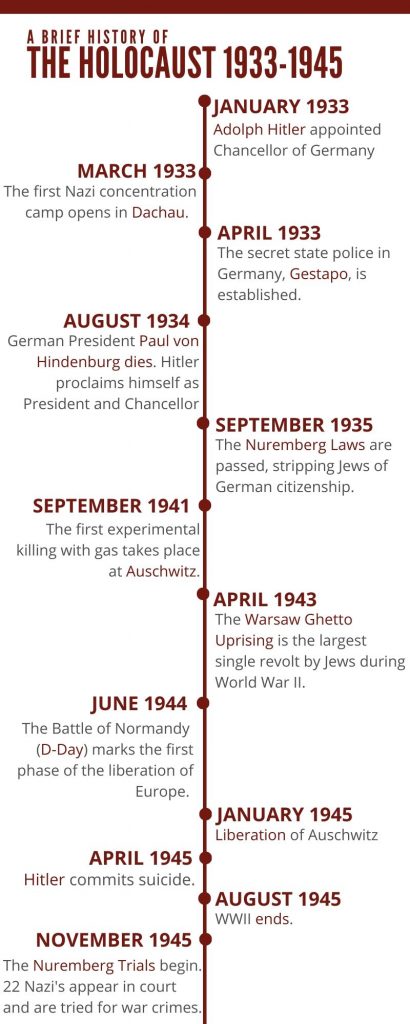

The reason behind this mystery is a story of survival. Lauren helped me understand this as she connected her childhood memory of her great-grandmother always wearing shoes to Thelma’s experience in the Holocaust. In the 1940s, Thelma and her late husband, Joseph, escaped a concentration camp in Poland and lived in a cave for two years. The living conditions were nearly unbearable, yet the two persisted. Due to the freezing temperatures of the cave, Joseph, a surgeon, had to amputate Thelma’s frostbitten toes. Hence, she never showed her great-grandchild her feet as she was covering up one of the many scars from her past.

As Lauren tells me this story, her head tilt restores its upright position, her forehead crinkles slightly ease up, and her ribbon-curled hair springs back into place. Meanwhile, chills run down my spine as I wrap my head around the hardships of Lauren’s family history.

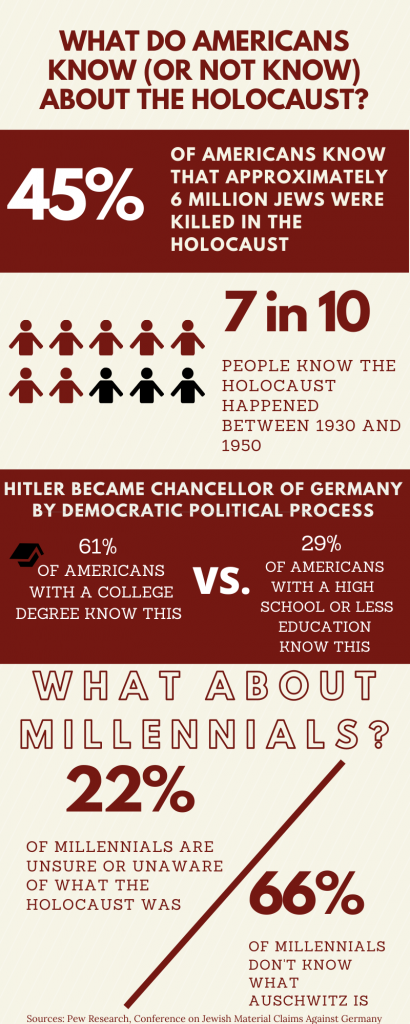

Thelma’s story, like many Holocaust survivors’, is a tale of repression, perseverance and legacy. This year not only marks 10 years since Thelma passed away, but also 75 years since the Holocaust ended. It has become the duty of young generations to keep learning about and remembering this time in history, yet we see millennials are losing power in their knowledge of this historical period. In fact, nearly a quarter of millennials, people between the ages of 23 to 38, are unsure or unaware of what the Holocaust was, and over half don’t know what the concentration camp Auschwitz is, according to a recent study by Pew Research.

While the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz is paralleled by a dying generation of its survivors, a lack of education on the Holocaust amongst millennials and a rise in anti-Semitism, efforts across the nation are coming to fruition to commemorate this period of history. Museums in the United States have set up special exhibitions in honor of this anniversary, such as the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York. This museum created a living memorial to the Holocaust in a new exhibit called “Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away,” which has curated over 700 original objects and 400 photographs from the Holocaust. In effort to increase museum attendance, the Illinois Holocaust Museum is offering free admission on the 20th day of each month in 2020. Over on the west coast, the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust is partnering with USC Shoah Foundation to create a new interactive exhibit entitled “Dimensions in Testimony” where people can virtually interact with Holocaust survivors by asking them questions that will prompt responses from pre-recorded interviews.

The digitization of Holocaust education efforts come at a critical time in history: archives are modernized to help us remember survivors, and to adapt to lifestyle changes in the midst of a pandemic that prohibits visitors from Holocaust museums. That said, Holocaust remembrance remains strong despite setbacks in physical distancing. On April 21st, the United States Holocaust Memorial in Washington D.C. aired the first live stream of Holocaust Remembrance Day. The online ceremony featured tributes from survivors and featured a pre-recorded statement from Elie Wiesel, who is best known as a Holocaust survivor, activist, and founder of the museum. The viewers were also able to participate in reading the names of Holocaust victims, a tradition that pays homage to those lives who were lost. One of those lives, Thelma Zimmett, carries a story that is undocumented in history and only the Milstein family passes on the oral legend of this Holocaust survivor. Lauren gave me the privilege of sharing Thelma’s story with you all now.

“I want people to know the Holocaust happened and my family is a direct impact of it,” Lauren said, as she shares about family history. “If you don’t believe it or think it’s wrong, well this is what happened to me and you need to know it happened.”

Thelma Zimmett was the type of great-grandmother that never missed one of Lauren’s dance recitals, that left long voicemails on the answering machine as if you had picked up the phone and had a recipe for the perfect pistachio pound cake that no one can seem to repeat. On top of that, Lauren says her great-grandmother was a “fighter.”

Thelma didn’t share much with her family about her experiences in the Holocaust, but she did talk about the horror of watching one of her five sisters get shot right in front of her by the Nazis, the hope she had to find to survive in a cave after escaping a concentration camp in Poland, and the prominent scar she had on her chin that she got from splitting it open after hitting it on the boat she rode to immigrate to America.

Holocaust education was engrained in Lauren’s childhood as she grew up hearing these stories from her great-grandmother and seeing her family as physical evidence of products of survival from that era. In the classroom, however, this was not the case. “When we covered [the Holocaust] in high school it was a section of a chapter,” Lauren said. “It was six million people killed and they’re just going to graze over this like nothing happened. It’s crazy to me.”

Efforts to honor the anniversary of the Holocaust extend beyond cultural means and are now being seen in education and legislation. This year on International Holocaust Remembrance Day (January 27th), the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Never Again Education Act. This bill strives to enhance Holocaust education in America by expanding the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s education programming by providing online resources to teachers across the nation to increase Holocaust awareness. The nearly $10 million fund would expand the Museum’s programs to set up workshops for students and pair teachers up with different Holocaust education centers to refine their curriculum. This bill is currently being reviewed by the Senate and it needs to pass in order to reform education across the nation. If passed, the funding would help shore up a deficient Holocaust education; only 11 states require schools to teach the topic. This statistic prompts the question; Will younger generations be accurately informed about this time period and what happens if they are not?

“With the passing of the Holocaust survivor generation, that voice is not as prominent, it’s not as visible, it’s not as widely heard,” said David Myers, director of the Luskin Center for History and Policy at UCLA. “I do think there’s a generational piece to this and it just reminds us of just how much more vigilant we need to be.”

For millennial and Los Angeles native, Rachel Glouberman, she, like Lauren, grew up with knowledge of the Holocaust as a staple of her education. Rachel, 23, attended private Jewish schools from kindergarten through 12th grade and refers to her childhood education as a “bubble” of Jewish studies in a world where Holocaust education isn’t always prioritized. “It didn’t even cross my mind that people didn’t really know what the Holocaust was or didn’t think it happened,” Rachel said. “It’s really important to learn about it not just as a Jew, but it’s a big part of history and learning about the past makes you more sensitive to other types of people. We all need to learn from past mistakes and history to not have it repeated.”

A recent study by the Claims Conference found that while there were over 40,000 concentration camps and ghettos in Europe during the Holocaust, 49 percent of millennials cannot name a single one. This misinformation poses a threat to the Jewish community with the current lack of knowledge on this period in history, Myers said.

“I think the more ignorance we have, the more likely it is that hate speech and behavior will increase,” Myers explained. “Education and exposure to not just the depths of the tragedy but the human dimensions of it can have the effect of immunizing against a descent of that kind of violent nature.”

This violent nature Myers described can be seen in the rise of anti-Semitism in the United States especially in the past few years. While there is not a proven correlation between a lack of education and anti-Semitic attacks, the surge in hate crimes against Jews is often tied with extremism and anti-Semitic beliefs, according to Myers.

“There are really two seemingly contradictory positions that one can hear,” Myers said. “One, that there was no Holocaust and two, that Hitler didn’t finish the job. Both of those things often come from the same source of extremist white nationalist right.”

The Anti-Defamation League tracks anti-Semitic attacks across the nation and found the year 2018 was the third-highest year of anti-Semitic attacks since the 1970’s. More recently, anti-Semitic hate crimes in Los Angeles increased more than 60 percent between 2018 and 2019, according to LAPD. Comparably, more than half of hate crimes reported in New York City last year were directed at Jews. More recently, this past April an Alabama synagogue was vandalized with anti-Semitic graffiti on the facade. These attacks continue to take place across the nation and often happen in our own hometowns. Such is the case with Rachel, who shared her experience after Nessah, a nearby synagogue in Beverly Hills, was vandalized in an anti-Semitic attack.

“It was a reality check,” Rachel said. “You often hear about attacks in America but this one was closer to home and just 15 minutes from my own synagogue. I can’t believe that attacks still happen, and I couldn’t have imagined it would happen so close to home but it’s just a reminder of how real this problem is.”

Anti-Semitic acts can be defined by assaults, vandalism, and harassment, according to the Anti-Defamation League. The organization’s research has proven that each of these forms of attacks have doubled in the past five years.

The question still remains, how can we increase our education about this period in history? One answer to this question lies locally in a hidden gem located in the basement of Doheny library at the University of Southern California.

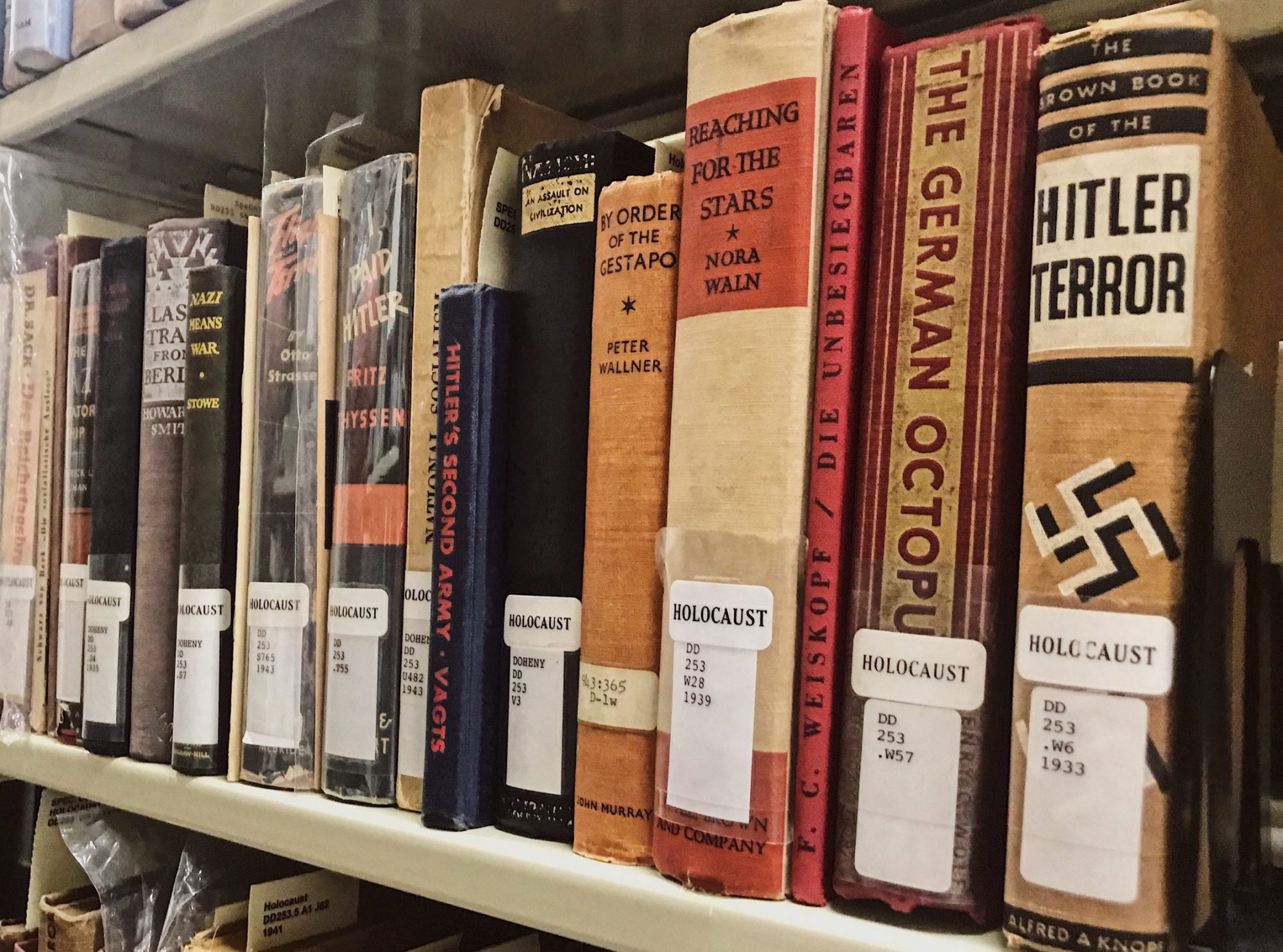

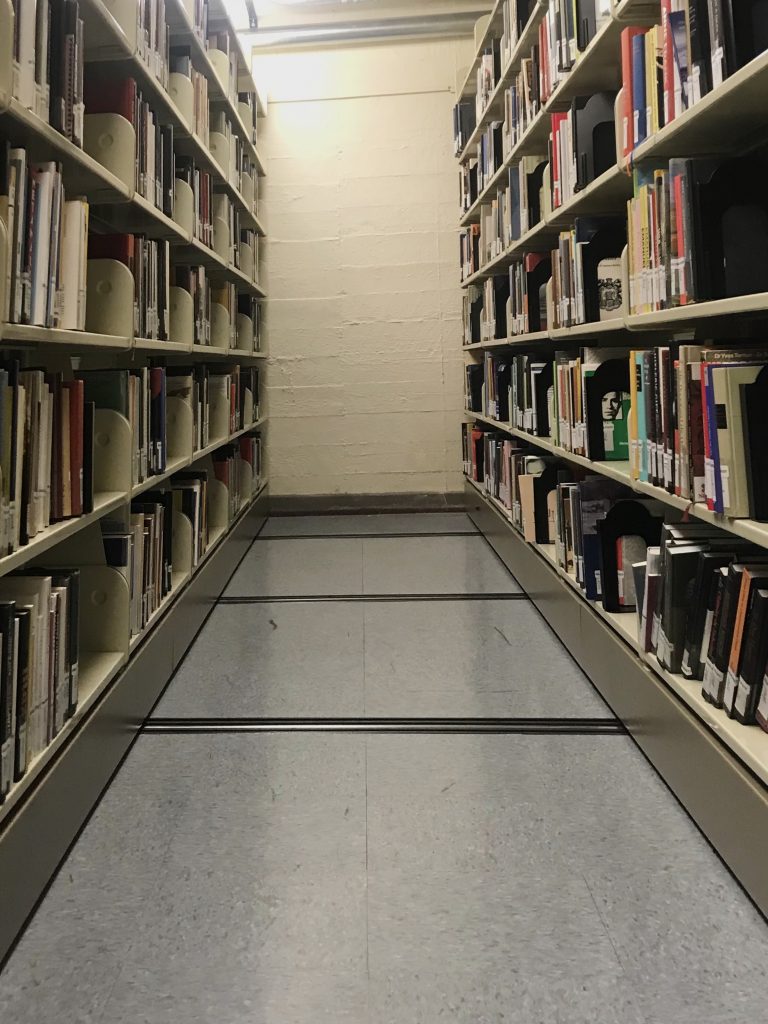

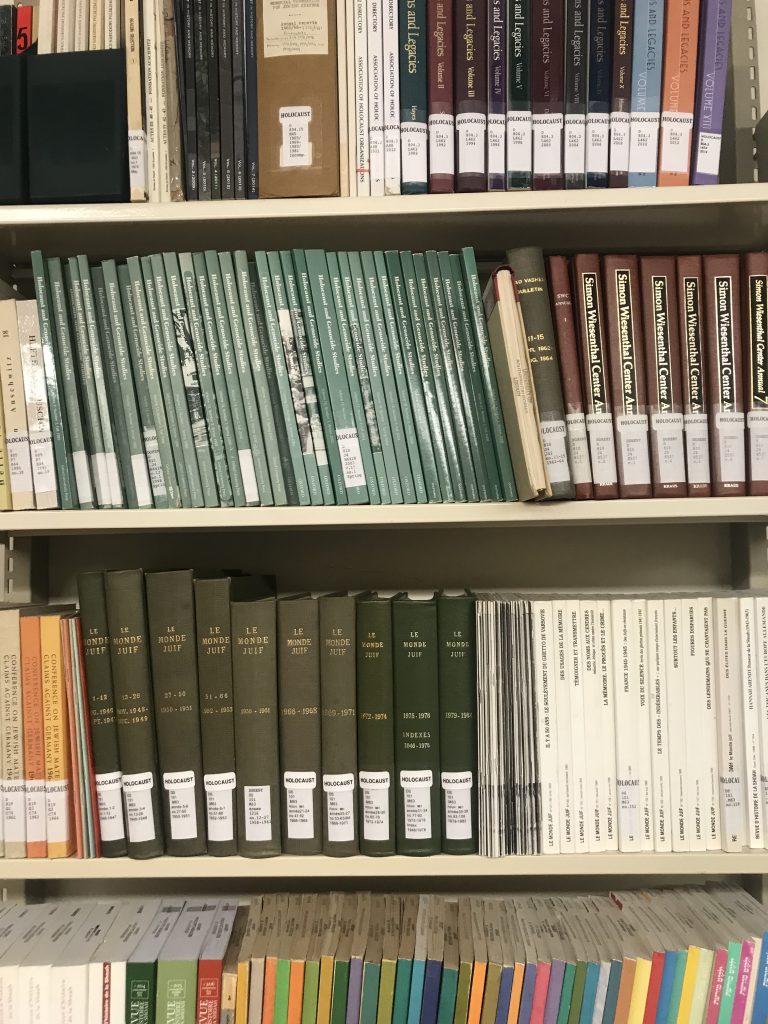

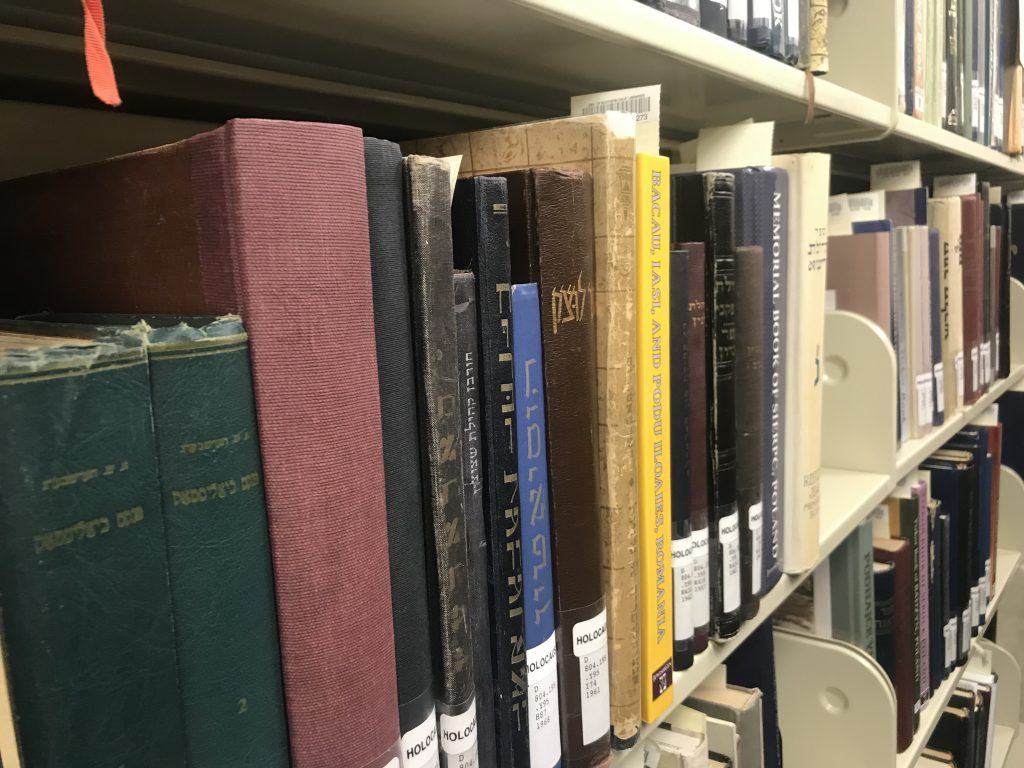

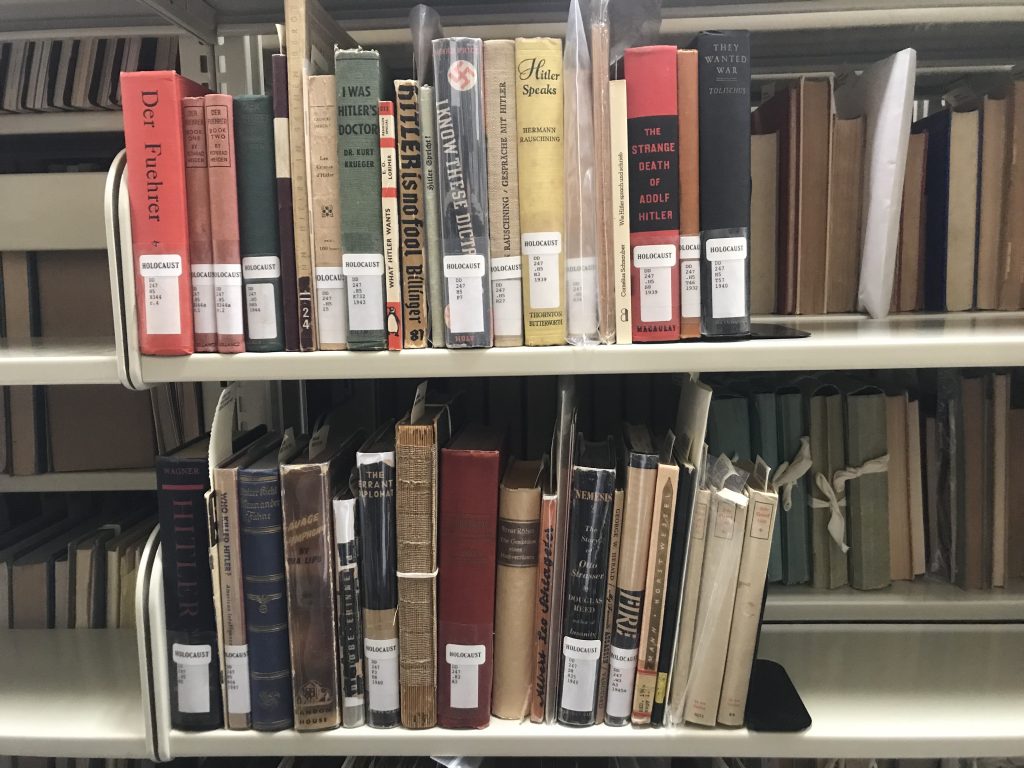

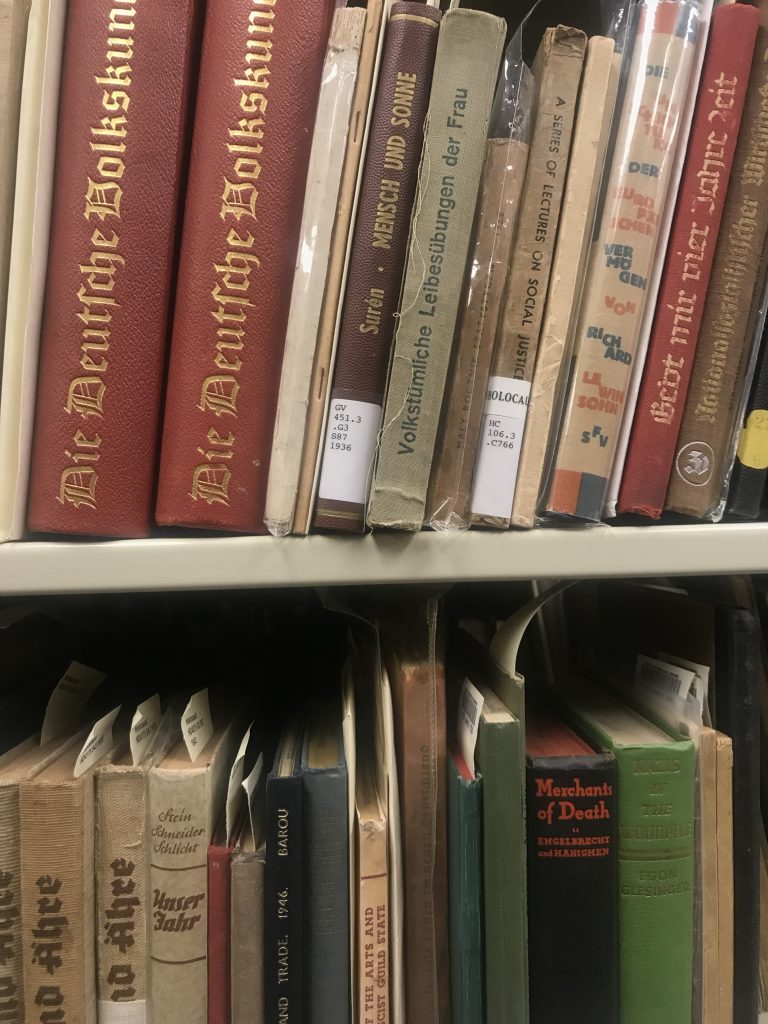

This hidden gem is USC’s Holocaust and Genocide collection found down two long winding flights of stairs upon entering Doheny library. The staircases lead to a mundane small door that looks into a room seemingly like any other room in a library. Opening the door to the entrance of the collection, however, the initial sight of thousands of books that line the shelves is simultaneously powerful and overwhelming. To be more precise, 19,000 volumes of Holocaust and genocide books are categorized, alphabetized and perfectly placed in what seems like endless aisles of historical records, informational works and educational resources.

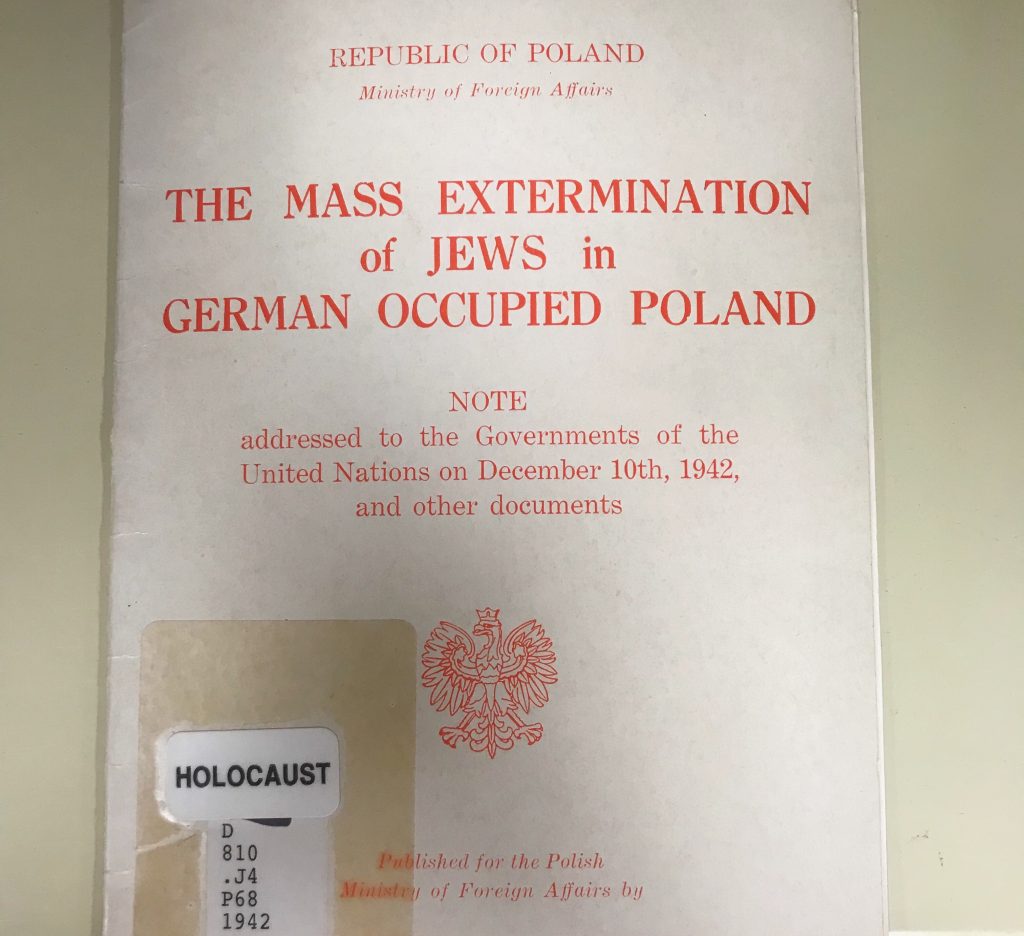

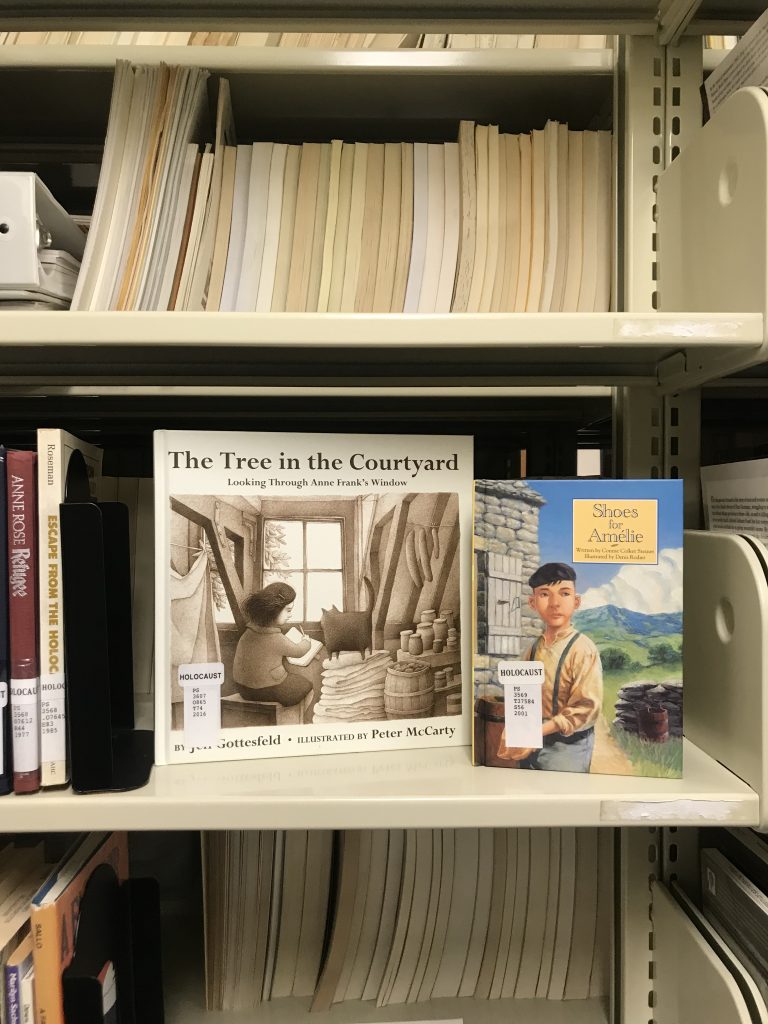

With over 36 languages represented in the collection, the topics range from original testimonials from survivors to art and music in the Holocaust to children’s books that help educators understand how to teach the topic to kids. There are even locked aisles that contain rare pieces to the collection that you need special permission to access such as an original Polish pamphlet from 1944 that is the first mention of what the Germans were doing at the time.

What is perhaps as interesting as the collection itself is the head curator for it, Lynn Sipe. The 77-year-old started this ever-growing collection 10 years ago and transformed it into the bountiful resource that it is today.

Sipe’s path to curating this collection was, as he says “serendipitous.” He grew up in a rural town in Kansas and never met a Jewish person until he went away to college at American University in Washington. “I didn’t know there were any Jews left,” Sipe said. “When I went to college, I didn’t know a lot about a lot things including the Holocaust for that matter. I’m not sure I never even knew the word until I was out of graduate school.”

When Sipe was working at USC, he came across a seller who was offering a collection of genocide books. He recalls quickly jumping on this opportunity and said he made the decision to start the collection from a research and structural point of view. “This story needed to be told and these records needed to be maintained,” Sipe said. “It’s not really a Jewish issue. It’s a human rights issue.”

Sipe purchased the initial collection and unpacked 385 boxes from the dealer in the same room that the collection exists in today. “The opportunity was very serendipitous that this collection came on the market at the right time we could curate a collection,” Sipe said. “Once that first purchase happened, it sort of all snowballed and took on a life of its own.” The collection has in fact snowballed into something quite extraordinary as it now serves as the largest academic collection of its type in the country.

Sipe retired five years ago but still volunteers two to three days a week to help maintain the collection. “Someday I will stop doing it, but I want the collection to continue,” Sipe said. “I never think of terms of legacy actually, but I want the collection to live after I’m gone.”

At the end of the day, this is a story of legacies. The history of the Holocaust and the tales of its survivors’ lives in an educational form in the words of curated books at USC. However, this type of legacy does not end when you finish a book or exit the library as it persists in the minds of our youth to continue to pass onto the next generation. Take for instance, Sipe. He was once a misinformed college student in regard to Jewish studies but now curates’ books on the Holocaust. Or Lauren, who serves as a modern day young adult working to change the narrative of ignorance on the Holocaust by sharing her story as a product of Holocaust survival. Whether it is 75 years since the Holocaust ended or 175 years, Holocaust education is multi-generational, and it starts with setting a trend now on creating a more informed future.

“My great-grandmother and her husband were people who stood up for what they believed in and didn’t let anyone get in their way,” Lauren told me as she reflected on her legacy. “Now, I want people to know this is my story. One day, I want my own great-grandchildren to know who they’re direct descendants of, and that’s a fighter.”

Hear from Holocaust survivors

The following videos were created by the Shoah Foundation. For more, visit https://sfi.usc.edu/video-topics.

Holocaust survivor Hedy Bohm on arriving at Auschwitz

Holocaust survivor Henry Flescher on survival

Holocaust survivor Lilly Ebert on liberation

Holocaust survivor Shalom Yoran on his mother’s last words