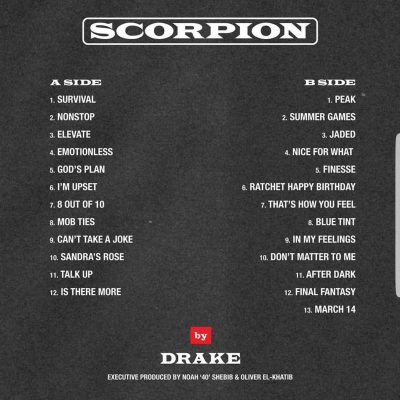

The end of Drake’s 2018 album cut “After Dark” doesn’t feature just any radio aircheck. It’s the voice of disc jockey Al Wood from Buffalo, New York’s 93.7 WBLK station, during a late-night broadcast of the Quiet Storm.

In a seductive tone, Wood lists musical acts Hall & Oates, Troop, Jill Scott, Luther Vandross and Chaka Khan — all characteristic of a Quiet Storm broadcast marked by smooth and romantic R&B.

Though the Toronto rapper included a nod to a Buffalo, New York station’s version of the format, the Quiet Storm and consequential genre has its roots in 1970s Washington, D.C.

“Back in the day, in the ’70s, black folks lived in the District,” said Dyana Williams, who is a former radio host and co-founder of the International Association of African American Music Foundation. For Williams, this is a crucial detail to note of the Quiet Storm’s origins.

Just three years before the first Quiet Storm broadcast aired, she took a job as a radio host at D.C’s 96.3 WHUR station, owned and operated by the historically black college Howard University.

Williams describes Washington, D.C. in the 1970s as a black utopia. Coming off the heels of the civil rights movement, the town, known as “Chocolate City,” had gotten a taste of black leadership with Walter Washington serving as the city’s first mayor.

D.C.’s black middle class was booming.

“I had a black dentist, a black gynecologist, [and] I banked at a black bank; everything black, black, black, black,” Williams said.

Central to the city’s community was the music of the time, with key ’70s artists like Marvin Gaye, born and raised in the city, Gil Scott-Heron living close by in Virginia, and the city’s own genre, Go-go reaching peak popularity.

Radio was also an important part of black life in D.C. and in other urban areas across the country.

In the ’60s, urban radio stations were vital players in the civil rights movement, encouraging listeners to attend protests. Moving into the ’70s, “over 250 stations aired primarily black artists, up dramatically from 100 just a decade earlier,” according to Forbes.

With programming known for providing “360 degrees of the total experience in black music,” WHUR was the “clarion voice for black folks in the nation’s capital,” Williams said of the station, with a slogan: “Sounds Like Washington.”

“We would play reggae to Miles Davis, from Earth Wind and Fire to Gil Scott Heron… it was a gumbo of [black] music, of all our different expressions and various genres.”

Williams, a Harlem native, dropped out of school to pursue a career in radio where she went by the name of Ebony Moonbeams, playing the newest black artists of the era. And during her time in D.C., she developed a relationship with two of the Quiet Storm’s key players: Cathy Hughes and Melvin Lindsey.

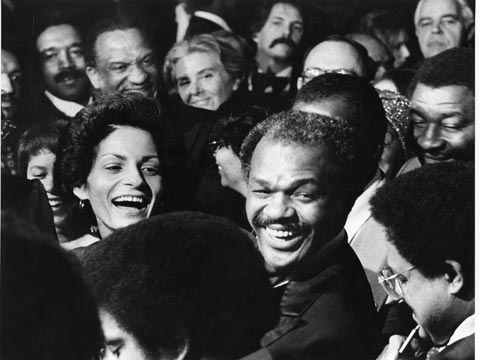

Marion and Effi Barry on January 2, 1979, after Barry was sworn in as mayor. (Photo credit: Star Collection, DC Public Library; © Washington Post)

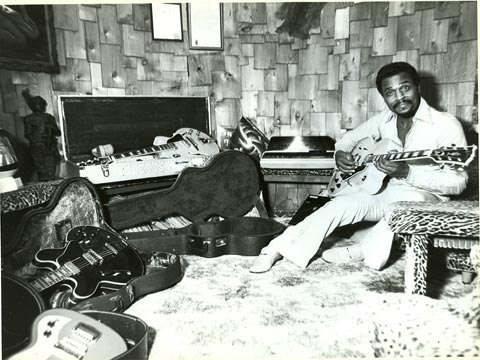

“The Godfather of Go-go,” Chuck Brown. (Photo courtesy Chuck Brown’s estate)

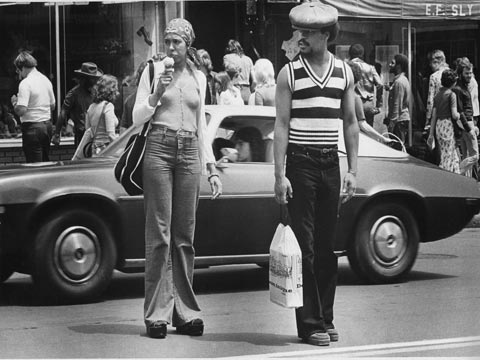

Pedestrians in Georgetown, July 1974. (Photo credit: Star Collection, DC Public Library; © Washington Post)

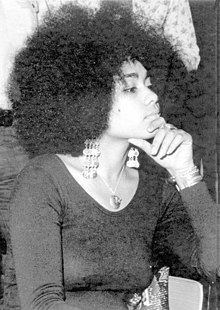

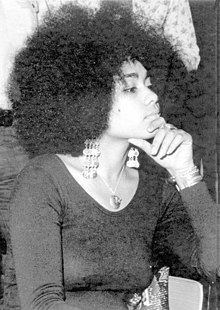

Dyanna Williams in the 1970s

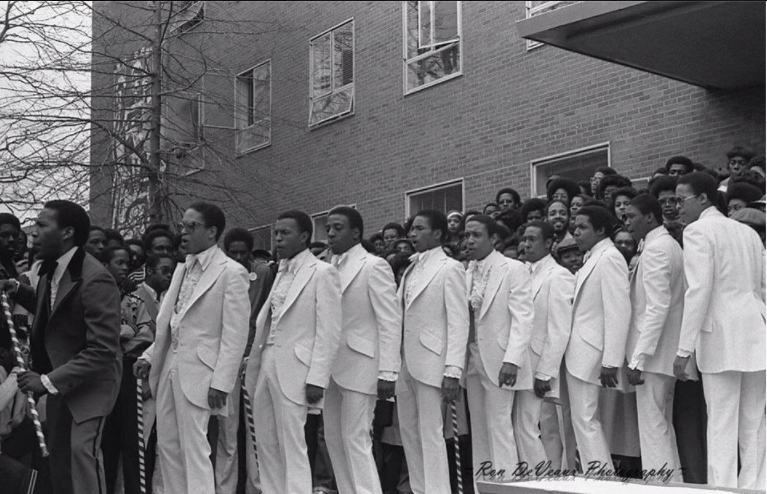

Howard University’s Bloody Xi Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi, 1979 (Photo courtesy of Elmer D. Ellis)

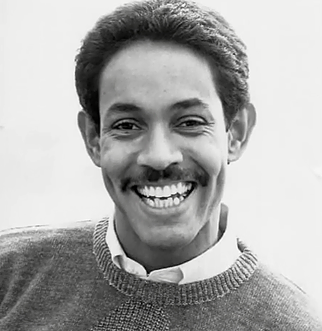

Melvin Lindsey, 1979 (Photo courtesy of EB’s Vintage Soul Music)

“We clicked instantly. It was just love at first sight,” Williams said of WHUR intern Melvin Lindsey. “He just had the right voice and temperament for evening [radio],” the format most-needed for D.C. residents at the time.

“People came home from work and they either put their records on, or they listened to the radio,” Williams said, but there was no specific program or format to accompany working-class D.C. as they unwind.

In a 2016 interview for NPR’s “How I Built This” podcast, single mother turned radio tycoon, Cathy Hughes, described the format’s target audience. “Single, unattached young people who still wanted to feel good about a Friday night or a Saturday night, even if they were by themselves. So, I structured a format called the Quiet Storm.”

Hughes would go on to build on the success of the Quiet Storm to found Radio One (now Urban One), a broadcasting company aimed at African Americans.

The first Quiet Storm broadcast aired on a Saturday night in May 1976, borrowing its name from Smokey Robinson’s 1975 album title track, “Quiet Storm.”

Williams defines WHUR’s new format as “several hours of ballads and mid-tempo romantic songs that nurtured intimacy and love in all aspects,” programmed with hits from across decades.

Robinson’s track was the perfect pairing for the new format. The almost-eight-minute ballad opens with an electric guitar riff and whistling winds as the former Miracles member sings of love “blowin’ through [his] life” like a quiet storm.

With Lindsey taking over as host and Robinson “breathlessly caressing the words’ ‘soft and warm, a quiet storm,'” (expressed by Rolling Stone’s Robert Palmer back in 1975) as theme music, the format took off.

“Melvin just was the ideal host. He didn’t get in the way of the music,” Williams said as she describes Lindsey’s mature voice and “exquisite taste.”

“[It] became the most popular show in the district at that time. Everybody was listening to Melvin Lindsey.”

The 1999 book “What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture” details why black people in the district were attracted to the format. Professor of Black Popular Culture at Duke University, Mark Anthony Neal, writes that songs programmed for the Quiet Storm were mostly “devoid of any significant political commentary and maintained a strict aesthetic and narrative distance from issues related to black urban life.”

The format countered other popular black music stylings of the time, such as Afrofuturism seen in groups like Parliament-Funkadelic or Marvin Gaye’s more socially conscious record “What’s Going On” (1971).

Melvin Lindsey himself described the Quiet Storm to Billboard as “a way to play mellow R&B music that appeals to a more upscale audience, but that is still gutsy enough for those who like downhome music.”

It wasn’t that the format was just the perfect soundtrack to unwind with. The Quiet Storm appealed to black middle-class aesthetics and an upwardly mobile D.C. that Williams arrived at in 1973.

In the same way Chocolate City was drawn to the format, so were station managers and radio producers from other cities with a bustling Black middle class.

“Other stations and other markets were mindful and aware of who we were and what we were doing,” Williams said of WHUR. “They emulated our formats, especially the Quiet Storm.”

“Name a city where there were black folks, and there was a Quiet Storm format.”

One of those cities was Philadelphia, where WDAS, a black-owned FM station, created their own version of the format titled “The Extrasensory Connection.”

Their Quiet Storm host was Tony Brown, a disc jockey who would then go on to host the cities’ first namesake Quiet Storm program at rival station, Power 99 FM.

“The Quiet Storm became a very integral component to WDAS radio really under Tony Brown,” said Jimmy Bishop Jr., a show host at WDAS. He’s the son of the station’s programming director and founder of Arctic Records, Jimmy Bishop. His mother is a longtime Philadelphia radio host, Louise Williams Bishop.

WDAS’ version of the format not only merged afro-futuristic stylings with “a psychedelic space transition at midnight,” said Bishop, but also was a platform for highlighting the orchestrations of Philly soul, a genre of late 1960s to 1970s soul music characterized by funk influences.

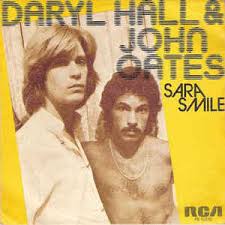

Bishop recalls his father’s close relationship with Philly soul production duo, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. The two would push the records of William DeVaughn, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes and even the blue-eyed soul pair, Hall & Oates for “The Extrasensory Connection.”

“Kenny would come in and talk about artists like Teddy Pendergrass, who is geared for [the Quiet Storm,]” Bishop said, pointing to the ’70s sex icon.

By the mid-’80s, the Quiet Storm spread to “as many as 40 percent of the nation’s 218 “urban contemporary” radio stations in the top 175 markets,” according to a 1987 article in The New York Times.

For WDAS, they would measure their version’s success by asking, “where [were] the ratings when the morning show got there at five o’clock in the morning?” said Bishop. The station would come out on the higher end, with a 4.0 share on the Abitron scale, opposed to a 2.0 or 1.0.

When Bishop started as a WDAS host in 1987, he also noticed that their Quiet Storm would spark conversations among listeners because the songs played would “tell a story,” typically revolving around romantic affairs.

“You would have discussions come up about cheating, about infidelity [and] about being a dog from the male standpoint,” he said.

Philly’s Quiet Storm and others across the country made space for more mature themes in black popular music as other styles, more aligned with partying like disco, were pushed into the mainstream.

“The thing about the Quiet Storm is that it really isn’t just a radio format, it is also a genre,” said former music industry executive and writer Naima Cochrane, speaking of how the Quiet Storm aided in breaking and resurging the careers of artists who didn’t fit into mainstream R&B.

Like many other music aficionados, she points to Smokey Robinson’s track as the start of a new subgenre of soul music and black popular music that made way for ballads.

Just as WDAS saw Philly soul hits creep into their Quiet storm due to their programming director’s relationship with Gamble and Huff, those same tracks — The Delfonics’ “Didn’t I (Blow Your Mind This Time)” or Darryl Hall & John Oates’ 1976 hit “Sara Smile —” would also serve as the early defining sounds of the Quiet Storm genre.

Cochrane notes that artists like Sade and her 1984 “Smooth Operator,” “broke with black audiences because of the Quiet Storm,” and in his book “What the Music Said,” Mark Anthony Neal also linked the genre to “the first opportunities for Black artists to experiment in improvisation and experimentation outside of jazz.”

Quintessential cuts from the genre include Patti LaBelle’s 1982 single “If Only You Knew,” which reached No. 1 on the Billboard R&B chart and No. 46 on the Billboard Hot 100, and Marvin Gaye’s classic “Sexual Healing.”

Despite the success of these singles, new subgenres like New Jack Swing (think “Groove Me” by Guy or Janet Jackson’s 1986 “Control” album) and R&B that incorporated more modern production techniques entered the mainstream, providing competition.

“Once New Jack Swing came into play in the ‘90s, [Quiet Storm] ballads were left on the wayside,” said Cochrane of the subgenre of black pop music.

The Quiet Storm toyed with the stylings of New Jack Swing with songs like Babyface’s 1990 solo hit “Whip Appeal” but failed to stay in touch with younger audiences.

“People started feeling like [Quiet Storm hits] were too polished, too boujee and too shiny as musical compositions.” Yet the Storm endured into the ‘90s, providing room for the voices of Jill Scott, Maxwell and their “‘please baby, I love you, I need you, I want you,’ R&B,” she said.

Through the ‘80s and ‘90s, not only did black music change with hip-hop’s rising popularity and numerous subgenres, but the rise of corporate radio entities as opposed to individually owned and operated stations affected the format.

Larger media companies purchased many black and urban stations, including WDAS. Beasley Broadcast Group bought WDAS in 1994, and then ownership shifted to Clear Channel Communications (now iHeartMedia) in 2000.

The Quiet Storm’s original home, WHUR, is still owned and operated by Howard University.

“Clear Channel gobbled it up,” said Bishop of the unique programming at the station. “It was more cost-effective to have one [disc] jockey for all black radio stations that they owned, [which was] 70 or more in 70 different markets.”

This meant, as Bishop put it, “some white guy would sit in his underwear in Nashville, Tennessee and program black radio stations for people across the nation.”

With hip hop gaining traction (albums like “Niggaz4life” (1991) by N.W.A surpassed “Out of Time” (1991) by R.E.M. to become the most successful project in the country) new management at black radio stations saw more value in rap and R&B with hip-hop stylings.

Black radio split into two formats: “urban mainstream,” which plays a mix of rap and R&B and targets 18 to 34-year-old listeners, and “urban adult contemporary,” which mostly plays pure R&B, aimed at listeners aged 25 to 54 — where the Quiet Storm landed.

Despite losing its stronghold on urban radio, Cochrane said the vulnerability present in Quiet Storm R&B “was a consistent theme in R&B music up until the early 2000s.”

She previously worked as John Legend’s product manager at Columbia Records, where she saw radio formats transition, affecting artists like Legend and his ability to break records.

“John is a crooner,” said Cochrane of earlier tracks like his famous “Ordinary People” or more recent singles like “All of Me.” “His ballads never started on urban mainstream radio. They always started on urban adult [contemporary] radio, which is where the Quiet Storm lives.”

“It’s a slower-moving and slower-selling format,” she said of the Quiet Storm and urban adult contemporary. “In the 21st century’s music landscape, you have to have an up-tempo hit to make it to mainstream radio,” not just ballads.

Today, the format is still present, celebrating 44 years on the air in 2020. Melvin Lindsey left the station after nine years of hosting the Quiet Storm and took it to rival D.C station WKYS. He later became a presenter on “Midnight Love,” a late-night music video segment on Black Entertainment Television (BET) until he died from complications of AIDS in 1992.

WHUR still airs a weekday Quiet Storm. Although no specific data tracks the number of Quiet Storm formats that exist today, urban adult contemporary radio is the top African American radio format making up 28.5% of the African American radio audience, according to Forbes.

Modern Quiet Storm broadcasts are more versatile and not regulated to one age group or era of artists. Cochrane said this versatility is the foundation of the radio format.

“You can play Fantasia, H.E.R or Daniel Caesar, and they might go back to back up against Earth, Wind and Fire or Marvin Gaye’s ‘Distant Lover’.”

“The Quiet Storm was you being able to select a playlist on Spotify before you could select a playlist on Spotify…one big-ass mixtape,” she said.

Many of today’s major streaming services curate playlists that cater to a specific mood — from a playlist of songs to cook to or a collection of lo-fi hip-hop beats. Serving as a precursor to the curation of songs now provided by TIDAL or Apple Music, the Quiet Storm aggregated a musical aesthetic.

That same vibe is helping the careers of new Quiet Storm-leaning acts who have found alternative paths to reach fans outside of radio.

A 2018 Rolling Stone article points to the success of artists like Brent Faiyaz, who has over 85 million streams on Spotify. His success on the streaming platform bolstered his single “Gang Over Luv,” which in turn reached mainstream radio.

Hip hop is still as popular as ever, but streaming services are where today’s Quiet Storm songs and artists see monumental success. Along with Faiyaz’s catalog and Drake’s “After Dark,” singers like Snoh Aalegra, Summer Walker and Lucky Daye are producing new, slower-tempo melodies with “[a] focus on lyricism, which we had lost a little bit,” said Cochrane.

“Music usually cycles back about every 20 years,” she said. “Now, [we finally see] some of the feels and sounds of the Quiet Storm. It just took an extra 10.”

The Quiet Storm Quiz

Results

Brush up on your reading, there’s a lot more to learn about The Quiet storm.

#1 Whose 1975 song influenced the Quiet Storm radio format?

Stevie Wonder

Stevie Wonder  Smokey Robinson

Smokey Robinson  Teddy Pendergrass

Teddy Pendergrass  Michael Jackson

Michael Jackson #2 What college’s radio station was the original Quiet Storm produced by?

Howard University

Howard University  Hillman College

Hillman College  George Washington University

George Washington University  Bennett College

Bennett College #3 Who was the original host of the Quiet Storm?

Smokey Robinson

Smokey Robinson  Dyanna Williams

Dyanna Williams  Melvin Lindsey

Melvin Lindsey  Cathy Hughes

Cathy Hughes #4 Cathy Hughes appeared on which NPR podcast to talk about her radio career?

Pop Culture Happy Hour

Pop Culture Happy Hour  How I Built This

How I Built This  Code Switch

Code Switch  Fresh Air

Fresh Air #5 In which Drake song did he sample a radio aircheck of disc jockey Al Wood from Buffalo, New York’s 93.7 WBLK?

I Get Lonely Too

I Get Lonely Too  Jodeci Freestyle

Jodeci Freestyle  Trust Issues

Trust Issues  After Dark

After Dark #6 Which one of these modern artists would not typically be featured on a Quiet Storm program?

H.E.R

H.E.R  Summer Walker

Summer Walker  Justin Bieber

Justin Bieber  Snoh Aalegra

Snoh Aalegra #7 Which 1970s blue-eyed soul act has a hit characteristic of both the Philly soul & Quiet Storm sound?

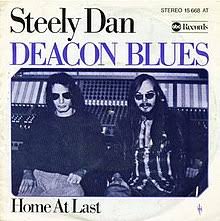

Steely Dan

Steely Dan  Darryl Hall & John Oates

Darryl Hall & John Oates  Bobby Caldwell

Bobby Caldwell  Michael McDonald

Michael McDonald #8 BONUS: Which rap group from the golden era of hip-hop has a song titled “Quiet Storm” ?

A Tribe Called Quest

A Tribe Called Quest  NWA

NWA  Mobb Deep

Mobb Deep  Wu-Tang

Wu-Tang