California spends less per student than almost all other states in the country, at nearly $3,500 less per student than the national average. As a result, the L.A. Unified School District (LAUSD) is struggling.

Financial reports state that the district’s deficits are reaching figures close to $600 million. This year, the California School Dashboard showed that 110 L.A. Unified schools require assistance due to low-performance.

Couple this with Los Angeles’ rapid demographic changes, new schools opening regularly, and misallocations of resources — the product is a drastic financial problem impacting the quality of schooling Angelenos are receiving.

LAUSD has lost 245,000 students in the last 15 years, each student representing thousands of dollars that would have flowed to local public schools. Just over a year ago, teachers held a seven-day strike protesting a lack of funding.

Changes since have been small. Some teachers, especially at local district public schools, still feel strapped for resources that make them unable to provide high-quality instruction.

Adriana Chavira, an LAUSD teacher at Daniel Pearl High School, explained that a lack of finances impacts schools’ ability to offer students opportunities outside of the physical classroom.

“We need money for field trips, we don’t have money for buses. We don’t have money for conferences for teachers to go to learn new lessons, learn new curriculum,” she said.

Funding to schools is allocated at the federal, state, and district levels, yet, the majority of money flowing into Los Angeles schools comes from the state.

In California, there is something in place called the Local Control Funding Formula or LCFF, which determines the amount of money given to each school based on enrollment or the number of students at that particular school, attendance, and the number of high-need students (i.e. English language learners, foster youth, special education kids, or those in need of free or reduced lunch).

Chavira explained that fewer students in schools can mean significantly less money for an individual school.

“If we don’t have the enrollment numbers, even if it’s by one or two, we lose a staffing position, and that’s happened to us several times,” Chavira said.

LOOKING LOCAL

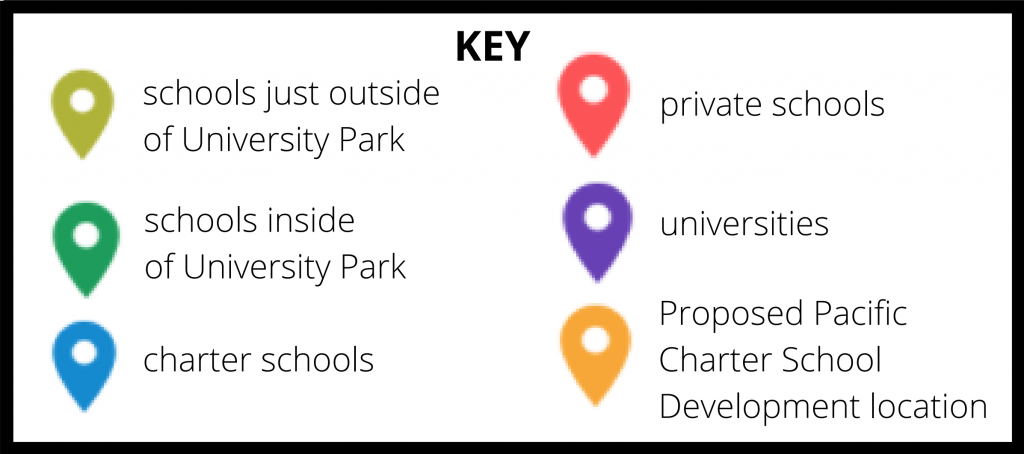

The map below of the University Park neighborhood, north of the University of Southern California, is an example of how many areas in Los Angeles have large numbers of schools in a concentrated area.

On January 21, 2020, the Pacific Charter School Development filed paperwork to build a new charter school at 1517-1531 W 23rd Street, which would threaten the enrollment and funding of at least eight local public schools and one charter school already in the neighborhood.

Community members were quick to oppose the school and Council District Eight Representative Marqueece Harris-Dawson’s office stated at a community meeting that they will “appeal the school every step of the way.”

Residents and community representatives in University Park are not alone in their sentiments.

FUNDING BREAKDOWN

As California has 1,300 charter schools, many are quick to blame charters for public district schools’ financial problems. Both district schools and public charter schools rely heavily on district and taxpayer funds — they receive a state grant for every student and more money for each higher-needs student they educate.

California’s Charter School Act was enacted in 1992, promising funding rules such as “base per-pupil revenue limit funding equal to that of its school district.” This coupled with reforms in the early 2000s means that funding is about the same for charter and district schools that are public. The only difference is that charters do not receive facility funding.

While every student that leaves a district school for a charter does impact their old school’s funding, school reform expert Gib Hentschke said that charter schools are not the only ones to blame. LAUSD has been behind the curve at adapting to changes.

“There are more schools for fewer kids, that’s going to be tough for anybody,” Hentschke said. “The real fundamental problem that’s showing up is that LAUSD is having to figure out how to scale down and restructure itself both centrally… and as schools to deal with declines in enrollment. That is a huge problem!”

Hentschke also stated that rising health and retired employee benefits suck money away from students. Fourteen percent of district budgets are spent on teacher benefits, which is more than the amount L.A. Unified spends on books and school supplies, according to L.A. School Report.

Anita Landecker, CEO of ExED, a nonprofit monitoring charter school finances, expressed similar concerns about how LAUSD chooses to spend its money.

“LAUSD built 130 schools about 5 years ago, between 2005 and 2015. They built a lot of schools at the same time as they had significantly fewer students because of immigration and lower birth rates… especially elementary schools that are now under-enrolled. It would make more sense to consolidate some schools,” Landecker said.

The district should also work with the state to reevaluate charter school approval rules. Charter school authorization law is highly decentralized and allows for various bodies to be “authorizers.”

According to a Harvard University study, California now has more authorizers than any other state and “oversees more charter schools than any other district in the country.” Oversight power is in the hands of many boards and schools can be approved at a state, district, or county level.

There is no streamlined communication and a prospective charter school can just go to another district or to the state to get approved, even if they are denied by LAUSD. Charter schools can get approved without conversations with the districts themselves and regardless of if there are sufficient funds or the capabilities for another school.

TIGHTER BUDGETS LEAD TO DECREASED QUALITY

The current influx of schools for a limited number of students also means educational quality deteriorates as budgets become tighter. LAUSD is not only struggling with keeping up with demographic changes, but student achievement is also low. A total of 20 L.A. Unified schools are listed in the state of California’s bottom 5 percent of low-performing schools.

While Landecker agrees that it is fiscally irresponsible to open unneeded schools as this will only exacerbate the financial problems of public school districts, she stated that sometimes a new school is the only option. L.A. Unified is leaving its students behind and charter schools are more attractive to many low-income students as they provide higher achievement and are perceived to have more opportunities.

“I could show you neighborhoods in South L.A. where only 7 percent of kids are proficient in math,” Landecker said. “If a school wants to start because LAUSD is unable to figure out or can’t, it attracts students.”

Parents say they choose public charter schools over their district school because of academics, the more personal relationships with parents, and safety.

“I appreciate that the school sets high standards for curriculum, behavior and appearance. The school is strict with behavior and appearance,” Jose Lopez, whose son goes to Collegiate Charter High School of Los Angeles, said in a Google review of the school.

“In my experience, I would go so far as to say that this school is better than any public high school in the area,” Lopez added.

“I saw the difference from the public school, they really worried for the students and parents,” said Jose Reyes of Alliance College-Ready Middle Academy 12, where all his children attended.

One parent of three children in LAUSD, Isabel Salguero, stated that the local district public school is only sufficient when it offers opportunity. She sent her son to a charter school while her daughter remains at the district public school.

“My daughter goes to Foshay Learning Center, not because the school is good or pretty, but because she is in the program called the USC McMorrow Neighborhood Academic Initiative. I think it is a good program and I am happy,” Salguero said. “If for some reason she no longer qualified for the program, I think I would change her to a different school.”