She wasn’t expecting to receive a phone call that would change her life – one that would make her worry about her health, challenge her sense of personal responsibility that she prided herself so much on, and most importantly, question her entire sense of self-worth.

“Your results came back,” her gynecologist told her. It was just another Wednesday afternoon. She was driving home from her summer job volunteering at the local daycare. Her plans for the evening consisted of eating dinner with her family, studying for the online economics course she elected to take, and maybe even staying up past her bedtime: under the covers, staring at the glaring light from her iPhone, with that childish smile on her face as she texted the new guy she was seeing. This was the first guy she had truly been excited about in a while. And she was smitten, at the very least.

“You tested positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2,” her gynecologist continued in what sounded like a harsh and judgmental tone. “Did you really not know you had this?”

Julia – whose name has been changed to protect her identity since she only agreed to tell her story with the promise of anonymity – was stunned. How could she have herpes? People like her didn’t get herpes. People like her were supposed to be pure, clean. She was a wide-eyed sophomore at an Ivy League university: smart, driven, and eager. But within seconds, that vague sense of confidence and certainty she had in herself and her future felt like it had been robbed from her – a feeling she never really noticed was there until it was gone.

“I was ashamed and disgusted with myself,” Julia said. “I convinced myself that I deserved this… deserved this for being irresponsible, slutty or whatever. And now this was now my punishment. Nobody was going to want me. Nobody was going to love me or think I’m sexy or worthy. Because now I’m dirty.”

What Julia didn’t realize, however, is that 1 in 2 sexually active people will contract a sexually transmitted infection by the age of 25. That globally, researchers estimate that about two thirds of the population under age 50 is infected with Herpes Simplex Virus 1.

And the numbers are soaring. According to the most recent data compiled by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), STIs are at an all-time high. Between 2017 and 2018, there were increases in many of the most commonly reported STIs – syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Syphilis increased 14 percent to the highest number reported since 1991. Gonorrhea increased 5 percent, and chlamydia increased 3 percent to 1.7 million cases: the highest number ever reported to the CDC.

There are multiple factors that play into why STI rates are rising. The CDC recognizes stigma as one of the main barriers from preventing and minimizing STI rates in the United States. The more we stigmatize STIs, the less likely people are to get tested or tell their partners. As a result, the STI epidemic in America will only get worst.

“Because of the stigma, people feel like STIs only happen to ‘certain kinds of people,’ and that they’re not a relevant risk to them. So, they don’t feel as though regular testing is necessary because they would ‘know’ if they were sleeping with someone who had an STI. They believe they don’t engage in activities with ‘those kinds of people,’” said Jenelle Marie Pierce, executive director of the STI project, a group that she founded in response to stigma against STIs.

“Even if someone feels they may potentially be at risk they’re reluctant to get testing because it’s not easily accessible. And people don’t want to say they’re getting tested because that leads others to ask questions like how come you’re getting tested?Are you sleeping with a lot of people? All these inaccurate assumptions about the sexual behavior behind what leads to contracting an STI.”

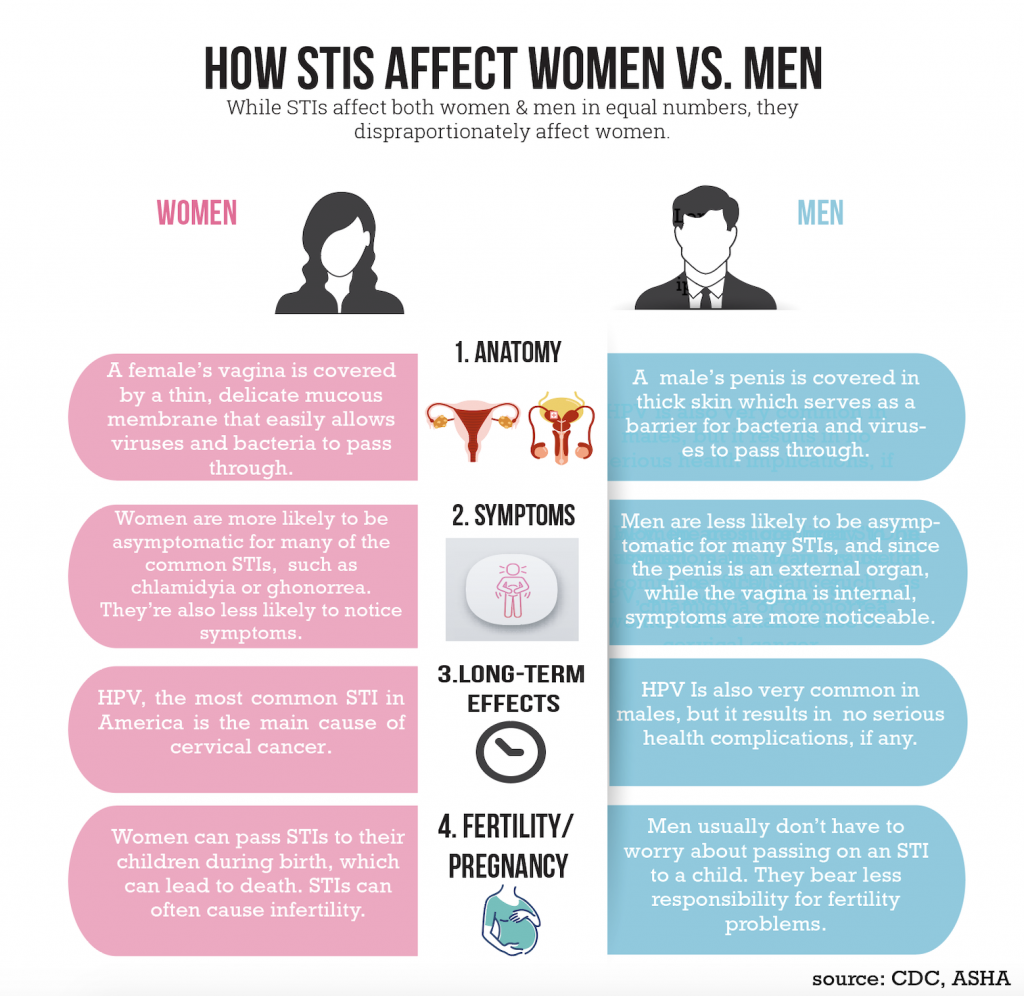

STIs become a significant problem when untreated – which often happens when people aren’t informed of the risks and aren’t getting tested regularly. And STIs are often asymptomatic – especially in women – which further reduces the likelihood of treatment.

But upon early detection, STIs can be cured or managed without having significant health impacts. Herpes is a viral infection, and while it cannot be cured it can be effectively treated with anti-viral medication like Valtrex. Aside from Human Papilloma Virus, which is the most common STI in America affecting nearly 80% of the sexually active population, the two most common STIs are chlamydia and gonorrhea – which can both be completely cured with a one-time antibiotic.

Sexually transmitted diseases are incredibly common – in fact there are over 110 new and existing STIs In the United States alone. What differentiates STIs from other illnesses and infections is that they’re passed through sex; and because of this, they often carry with them a psychological burden from the stigma associated with sex in our society.

“When people are diagnosed with an STI they start to believe massive amounts of misconceptions about themselves: that they’re promiscuous, have lots of sex with lots of people, are dirty and damaged, and they’ll never be able to find a partner or have a healthy sex life again. All the stuff comes crashing in and it disrupts an individual’s sense of self, their autonomy over their body, and empowerment over their sexuality and sexual identity,” said Pierce.

The Hidden Effects of an STI

Herpes wasn’t something Julia had thought much about prior to her diagnosis. She thought they were huge, disgusting blisters that her health teachers had shown the class to scare them out of having sex back in middle school. She thought that herpes and other STIs were only things that overly promiscuous, irresponsible people had to worry about.

She later learned the truth about herpes: that it can be managed, and that medicine has nearly eradicated the jarring and painful outbreaks often characterized in the media. Upon her diagnosis, Julia proceeded to take the anti-viral medication, Valtrex, daily and rarely felt anything during an outbreak other than slight itchiness similar to a yeast infection.

She soon realized the physical effects weren’t that bad, but the treacherous effects of her diagnosis were psychological: that the problem may not have been the virus she couldn’t get rid of, but the stigma that came along with it.

Obstetrician-gynecologist Johnathan Lanzkowsky said that many patients react to a STI diagnosis with feelings of guilt and shame. He said they commonly use words such as “dirty” to describe themselves and fear that current or future partners won’t want to be with them. Most importantly, he added, they feel a sense of responsibility – that they brought this upon themselves.

“You’re not guilty of anything because you contracted a particular virus, whether it’s an STI or coronavirus,” said Lanzkowsky, adding that an STI diagnosis is not an indictment of who you are as a person.

There is an abundance of research on the psychological effects an STI diagnosis can have. Researchers in Australia the University of Western Sydney studying women and STI stigma concluded that “the stigma attached to women with STIs is so profound and entrenched that they internalized the stereotypical views of women with STIs as promiscuous, loose, and dirty and subsequently carried these thoughts about themselves.”

These researchers essentially found that stigma and stereotypes associated with STIs caused women to feel tainted, deviant, and unworthy of love.

Further, there is ample research stating that negative psychological effects of STIs are often worse than the physical, and that women may deal with these detrimental psychological effects more than men.

“If you catch the flu it’s not really your fault,” Lanzkowsky said. “Sure, you could’ve taken some steps to avoid it. But even if you do take those precautions there’s no guarantee you won’t get it. It’s no different with STIs.”

The Woman’s Responsibility

It wasn’t clear to Julia where she might have contracted herpes. She was nineteen years old and had had five sexual partners – a number which she regarded as relatively low compared to most of her friends. She was immersed in the heart of college hook-up culture, where everybody seemed to be having casual sex with no real concern for consequences that came along with it. While she partook in this to an extent, her partners had all been consistent: most, she had been in an exclusive relationship with. To her understanding they were all “nice boys” who wouldn’t have something like herpes. And while she made sure to use condoms, she wasn’t particularly concerned about contracting anything. But now that she did have herpes, the internal shame came from her distorted belief that it was solely her fault and her problem.

“When you’re talking about women’s health, a lot of things are put on the women. With fertility and STIs, it’s always the women who feel damaged. But they often forget that they didn’t get this condition alone,” Lanzkowsky said.

The issue with STIs, such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, is that they affect fertility – something that has historically been associated with women. When Lanzkowsky has patients come in to discuss infertility problems, for example, he said he notices that men don’t even get a semen analysis most of the time; his patients assume that if they’re not able to get pregnant it’s the woman’s fault.

HPV, the most common STI in America is the leading cause of cervical cancer. Ninety-one percent of cervical cancer cases come from HPV, yet this virus very rarely has health implications for men.

STIs affect women and men in nearly equal numbers, but paralyzing shame is just one of the ways they disproportionately hit women.

Los Angeles-based psychologist Debra F. Langer, PhD, has seen the psychological strain an STI diagnosis has on many of her female patients.

“I think women feel so bad about it is because historically, women have just always had greater responsibility for pregnancy, birth control and self-protection,” Langer said. “Additionally, when there’s a promise of sex I do not believe men have such a sense of consciousness as women do. Women may want to use a condom, but not want to upset the guy in asking. And then women beat themselves up after because they neglected themselves to not upset a guy.”

Tracking the Stigma

Julia thought the fear, anxiety, and debilitating sadness she felt after her initial diagnosis would be the worst of it. Her friends and family members noticed she wasn’t herself, but she couldn’t bear the thought of telling them. The only thing that she believed could be worse than the way she was feeling right now, was people knowing about it.

“I thought I had a death sentence,” she said. “Because something I had placed so much value on in my life was being loved. I wanted to be loved by a guy so desperately and I thought that that was no longer a possibility because in my mind there was no world in that anyone would love me. That’s genuinely what I thought… in a certain way I still feel that way.”

The year following her diagnosis, she returned to having sex – with condoms of course. She learned the chances she could still spread it while on the medication and with a condom were almost miniscule. She managed to gain back her confidence sexually – but deep down she knew this newfound sexual confidence was just a mask for the horrible way she truly felt about herself. Deep down, she knew she was damaged.

It wasn’t until she found herself in a loving, committed, seemingly perfect relationship with the person she thought could be her forever, that the true trauma of the situation settled in.

“We had stopped using condoms, and there was always this level of guilt that hung over my head in terms of I’m keeping something from him, I’m not being completely truthful. But I had this extremely fundamental fear that was so much louder than me feeling bad about keeping this thing from him. And it was him not wanting to be with me because of this. But as our relationship progressed, the guilt became louder than the fear.”

When Julia finally mustered the courage to tell her partner, her worst fears came true.

He called her “a disgusting slut.” He told her he could never see a future with someone like that. He reiterated to her every fear she ever had about herself, that she ever had about her diagnosis – they all came true.

“The worst part was I couldn’t even blame him for his reaction. What he was feeling was completely valid. I had lied to him and put him at risk for my own selfish needs of not wanting to lose him.”

I found it hard to avoid my own tears as Julia told me her story. She had a virus. A simple virus. How could the stigma associated with this have been so blown out of proportion?

“Stigma comes from the fact that people have completely poor info that is making them more anxious than the truth,” said Lanzkowsky.

When Langer treats patients dealing with the psychological effects of STIs, she says the first thing she does is give them the correct facts and information to correct their notion of what it is they have and what it is they’re associating with it causing unwarranted shame and trauma.

Because what is the truth? STIs like chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis can be treated and out of your body with likely no harm if caught early. Herpes can be managed. And early detection of HPV can mean taking preventative measures for the cancer it could cause.

“I think a lot of this shame and stigma has to stem from what these infections and viruses were perceived historically,” Langer said. “Because now, you don’t necessarily intensely suffer physically from these STIs. But there’s some leftover shame.”

Debra Kirschner-Lanzkowsky, who is a fellow obstetrician-gynecologist and Lanzkowsky’s wife, said old patriarchies die hard. “It’s still a male-dominated society,” she explained, “and I think they try to make women feel bad about being sexually liberated.”

STI STIGMA on Biteable.

Why are Numbers Rising?

One of the things Julia learned to find comfort in is that she’s not alone. With just a quick google search, she realized how incredibly common STIs are, and how much the rates have grown in recent years.

Dr. Lanzkowsky believes these increased rates have to do with the increase of casual sex, and decreased condom use because the effects of STIs are no longer as threating as they once were due to advanced medication.

“I always ask my patients how many sexual partners they have had. And I can tell you that in my 25 years of treating women that number has gone up dramatically.”

“This increased promiscuity may be a reflection that people aren’t as afraid of dying from sex, among other things. STI’s aren’t really out there killing people anymore. And if you notice the main age of STI contraction is 18-24, teenage invincible years. People are least likely to use condoms if something out there isn’t necessarily scaring them to use them. That’s why part of my job is to stress the importance of condoms.”

The CDC has emphasized, however, that part of these rising numbers has to do with increased screening among certain groups. This essentially means that the increased numbers each year doesn’t necessarily mean more people are getting infected, it may just mean that more tests are being administered.

“When we talk about numbers rising it has to do with increased testing, and insurance providers covering the testing,” said OBGYN Lona Prasad, who is an assistant professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at Cornell University’s Weil Cornell Medical college.

Moving Forward: Beating the Stigma Once and for all

So, how do we combat this stigma? How do we reduce the detrimental shame plaguing so many individuals diagnosed with an STI?

Experts say that education is the only solution.

“It has to start with education, from early adolescence, about STIs, what they are, how to prevent them, when to suspect you have one, how to use a condom, and giving access to young individuals to condoms and free testing for STIs. The information must be presented in a way that shows that these diseases can happen, to anyone, no stigma, and the important thing is to seek care immediately,” said Mariana Stern, PhD, epidemiologist and professor of clinical preventative medicine and urology at The University of Southern California.

Many professionals and organizations have replaced the word “disease” with “infection” in an effort to increase accuracy in the meaning of a diagnosis, and reduce stigma associated with the name.

The American Sexual Health Association gives the reasoning for their implementation of the name change on their website where it states, “The concept of ‘disease,’ as in STD, suggests a clear medical problem, usually some obvious signs or symptoms. But several of the most common STIs have no signs or symptoms in the majority of persons infected. Or they have mild signs and symptoms that can be easily overlooked. So, the sexually transmitted virus or bacteria can be described as creating ‘infection,’ which may or may not result in disease.’ This is true of chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes, and human papillomavirus (HPV), to name a few.”

“Reducing stigma by changing verbiage is something we’ve done in the psychological community for a long time,” said Langer. “I think this must help to an extent.”

Lanzkowsky, however does not believe that the name change from disease to infection has destigmatized the term. He thinks the only solution to truly destigmatizing this term is getting rid of the word “sexually” at the beginning. He suggests the idea of calling it just an infection: like all others.

Changing the Tone

Julia’s gynecologist had called her up to inform her that she had herpes, prescribed her medication to take every day, and never once brought it up again at following appointments. This effectively bolstered her discomfort and shame surrounding her diagnosis.

Changing the conversation around STIs has been noted as a vital way to battling shame and stigma. Many doctors, including Lanzkowsky and Prasad, have noted how essential it is for doctors to be open and non-judgmental with patients upon giving a diagnosis.

“Usually a lot of what’s bumming people out isn’t even true,” Lanzkowsky said. “Anytime you talk about any health problem, you should use the real language. What are we talking about? And then provide accurate facts so people don’t make up their own facts they live with.”

Prasad’s approach is similar. When she provides patients with a diagnosis, the first thing she does is offer support. Then she explains to them how they may have contracted it, what the consequences may be (often if caught early enough there are none), and how they can protect themselves and partners moving forward. She emphasizes the importance of being open and honest about your sexual history.

“I always tell patients, ‘use condoms. And as time goes on be more open about it’. Being open about your sexual history shows your educated, well informed, and have self-respect. That level of self-liberation is a big part of being sexually liberated too.”

While there’s a different approach taken for non-curable STIs, like HPV and herpes, and the curable ones, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis, both Lankzkowsky and Prasad emphasize the same messages of fostering an environment with any sexual partner to openly discuss STI’s.

“As long as you’re open and honest about it, there’s no reason anyone with an untreatable STI can’t go on to have healthy, future relationships,” Lanzkowsky said. “This isn’t something you can’t move past.”

The End of Julia’s Story

It has now been four years since Julia received her herpes diagnosis. She no longer feels damaged and dirty. She realizes what she went through is a common struggle for women everywhere: that her condition does not make her a leper. She is still in a loving, committed relationship with the same boyfriend she was so afraid to tell, and who initially reacted so poorly.

Like Julia, it took time for him to come to terms with, and accept, the situation. Most of his anger stemmed from the fact that she had lied to him and put him at risk when they mutually made the decision to stop using condoms (even though this risk was minor since she was taking the medication each day).

Looking back, Julia doesn’t regret not telling him earlier – she believes she had waited until the earliest point that their relationship could handle it. He has since been able to understand her reasoning. The one mistake she believes she made, however, was taking the condom off before she was ready to have that conversation.

“It took this experience for me to learn that an STI doesn’t doom a relationship. It just may mean you need to be more careful and aware.”

Julia and her partner were able to move past it, and she is just as happy and comfortable in their relationship as she was before divulging the fact that she had herpes. But it wasn’t until recently, that they really started having an open dialogue about it.

“I knew I wouldn’t be able to be fully comfortable with this if I still felt it was something I had to tip toe around. That’s why I’ve recently made an effort to bring it into conversation and not treat it as an elephant in the room. This has helped me tremendously,” said Julia.

In addition to engaging in open dialogue with her partner about her condition, she attributes a lot of her newfound acceptance and lack of shame to her new gynecologist.

“Unlike my old gynecologist, my new one has allowed me to feel less shameful and accepting of my condition. We have future planning, we have those kinds of conversations, she doesn’t avoid it. She honestly led me to feel that it wasn’t anything I had to be ashamed of. The same way I take antibiotics when I have a cold, I take Valtrex for my herpes.”

Her road to acceptance, however, isn’t quite over.

“As much as I wish I could’ve done this interview with my name, and that I want to tell you I’m completely at peace with all of this I can’t,” she told me with a regretful smile on her face holding back tears.

“I still struggle with the voice in my head that tells me that my current boyfriend is the only person who could accept me, knowing I have herpes. That if we ever break up, I may never find someone else who will love and accept me because of this.”

She wishes more than anything that our world will see a future where this disproportionate stigma no longer exists. A world where the next girl who gets a herpes diagnosis doesn’t have to spend years of her life hating herself and questioning her worth.

She wishes more people could understand that having an STI can happen to anyone. That they know to careful, because you can get an STI from having sex just one time with one singular person.

She would tell someone going through something similar that this is something that happens to millions of people, and just because you have a diagnosis it doesn’t mean your life is over. Even untreatable STI’s can be very well managed. What you’re going through is normal. You can still be successful, go on to have just as bright of a future, have amazing relationships, and thrive.

As for herself, if she could go back in time and tell her younger self anything it would be this: “Don’t be afraid. You didn’t do anything wrong. You will be okay. I promise.”