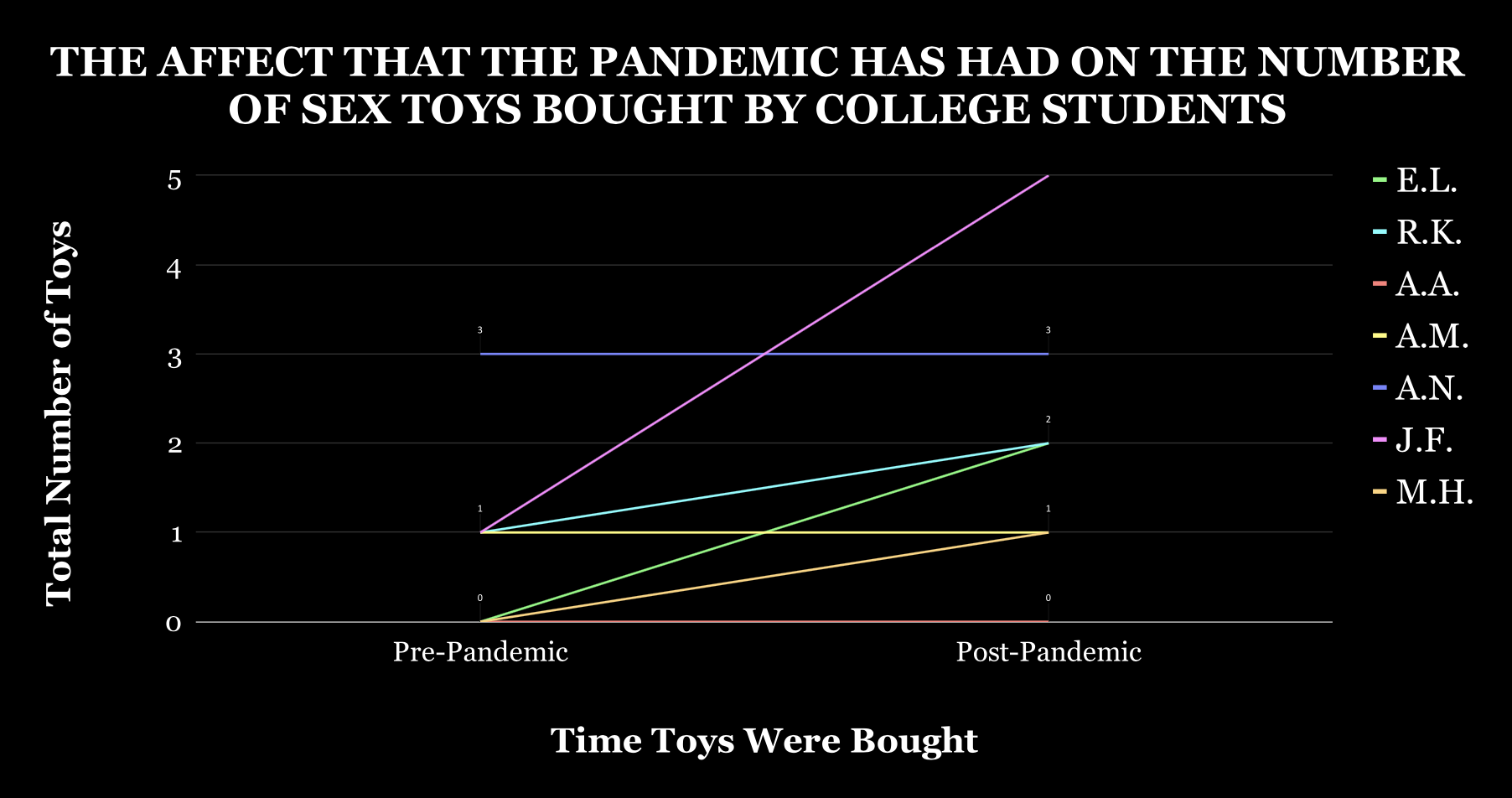

School is online. Clubs are closed. Bars are barely open. And fun, casual sex could lead to the spreading of one of the deadliest viruses in history. So what do students turn to for sexual fulfillment?

Sex toys. From restraints to vibrators. They’ve been getting snatched up more and more during the pandemic, particularly by college students. Thanks in part to the shutdown of most universities, students who would normally hook up during various social functions, classes and random meetings, have fewer opportunities to hook up.

Now, while it’s impossible to know which toys are being bought for partnered use versus self-pleasure or masturbation, it’s for certain that sex toy sales have been up since quarantine started.

In fact, according to a June article in the New York Times, Adam and Eve, a company with locations across North America and an online store, reported a 30% increase in online sales in March and April—right after stay-at-home orders were issued—compared to those same months last year. In an April feature in the Los Angeles Times, Chad Braverman, chief creative officer for sex toy company Doc Johnson, said sales were “up double digits in January and February compared with the previous year—before rocketing 100% year-over-year for the last five day of March.” In conversation with Jimi Famurewa for The Guardian, Polly Rodriguez, the CEO and co-founder of online sex toy shop Unbound, reported that there was a surge in sales on March 31. Then, there was a second surge on April 15, the day that the US federal government sent out checks to ease peoples’ financial burdens during the pandemic. Sales were up by 150% compared to the same time last year.

“We made more than $400,000 in April which, traditionally, is our slowest month; there was a wholesale order for $70,000 in a single day,” Rodriguez told Guardian.

Along with boosting sex toy sales, the pandemic is also changing the fabric of hookup culture, which is generally associated with United States college culture. Hookup culture encourages casual sex—sex without strings attached or any semblance of emotional intimacy or attachment—and has been fueled by various dating apps, including Tinder, Bumble and Hinge. Now with COVID-19, dating apps just aren’t hitting the spot anymore, both figuratively and literally. As a result, college students around the nation are looking for other ways to fulfill their sexual needs. While some are still taking part in hookup culture, weighing their physical needs against the safety of themselves and those around them, the days of hitting up a Tinder match to come over at 11 p.m. or going home with a stranger after a party are few and far between for a majority of college students.

For example, R.K., a student at Emory University, used to rely on hookup culture here and there for sexual gratification before quarantine. She details how she would swipe on Tinder and talk to someone for “a little bit” to see if she felt comfortable with them, before meeting up for a hookup.

M.H., a student at the University of Southern California, also recalls pre-pandemic hookup culture. She says that there were frat parties that her groups of friends would go to and then a regrouping the day after to exchange stories of each person’s hookup.

Now, things are a bit different.

“I’m not really having sex,” R.K. said. “It’s mostly just been me and my damn self.”

M.H. sympathizes.

“Hookup culture is almost non-existent now that we’re in the pandemic,” M.H. said.

R.K. continued to discuss how she’s been navigating singledom in the pandemic and how the situation has actually changed her relationship to sex, as its inaccessiblity has, in a way, forced her to focus more on her own wants, interests and turn-ons, rather than a partner’s.

“There’s not somebody else there who also has their own likes and things that they want to do,” R.K. said. “Before [the pandemic], I think I had the tendency to just go along with whatever [my partner] wanted to do, but now I’m thinking about what turns me on, what gets me in the mood.”

Again, M.H. relates, as she said that she’s also been able to “appreciate having sex with [her]self more.”

a student’s bedroom

her bedside table

her vibrator

But while the pandemic seems to have led to a reconnection with students’ own bodies and wants, it has also tinged casual sex with precariousness, so, as M.H. touched on, the social capital that was once so wrapped up in being able to talk about hookups and dating, has dwindled.

For example, R.K. and her friends aren’t hooking up with anyone, since they’re not vaccinated and don’t feel like engaging in sex would be safe. R.K. shares that the lack of casual sex and hook ups in her friend group has been leading to different kinds of conversations.

“Everyone in my circle is trying to be safe with the pandemic” R.K. reasoned. “We’re not having sex, so that’s shifted the conversations that I’m having with people, which I think has been a really positive thing overall.”

A.M., a student at the University of Southern California, participated in pre-pandemic hook up culture as well. He was on Bumble and Tinder and having sex “maybe two to three times a week” with multiple partners. Like M.H. said, there were also in-person events and parties that would happen over the weekends, which would be perfect opportunities for him to find a person to hook up with.

“There was a time where I was going out to events with the intention of just trying to hook up with a person,” A.M. said. “I think there is definitely a unique quality about coming to such a large university that is probably best described as a diversity… of humans, and I think that’s a really big allure or driving force in college hookup culture.”

Similarly, J.F., a current student at Columbia College, was a very active participant in hookup culture before the pandemic.

“My sex life was really taking off before the pandemic,” J.F. said. “I was hooking up with a lot of people off of Tinder and Bumble consistently—almost every weekend. I had a couple of one night stands with classmates. I was just having sex and enjoying myself.”

However, due to quarantine, J.F. says that they’ve had to rethink their sexual needs and desires, while A.M. says that his sex drive has lowered.

“[Quarantine has] created a need for some intentional ‘spicing it up,’” A.M. said. “It’s not as easy to get excited about things when every day is the same.”

His relationship to sex has been shaken. What once was an enjoyable activity, is now just another part of life that has been changed by the pandemic.

“Sex is a celebration of life and vitality and at the onset of the pandemic, a lot of the experiences that [go along with] vitality and life were stripped away,” A.M. said. “The pandemic definitely creates some holes that I have to spend a lot more energy trying to fill, whereas before, I didn’t need to do that.”

On the other hand, J.F. started to do some introspection: they started to ponder what sex actually meant to them, what meaningful sex looked like and how their sexual activity affected their sexuality, gender identity and sense of self. This self-analysis has led J.F. to develop a deeper relationship with masturbation.

a student’s bedroom

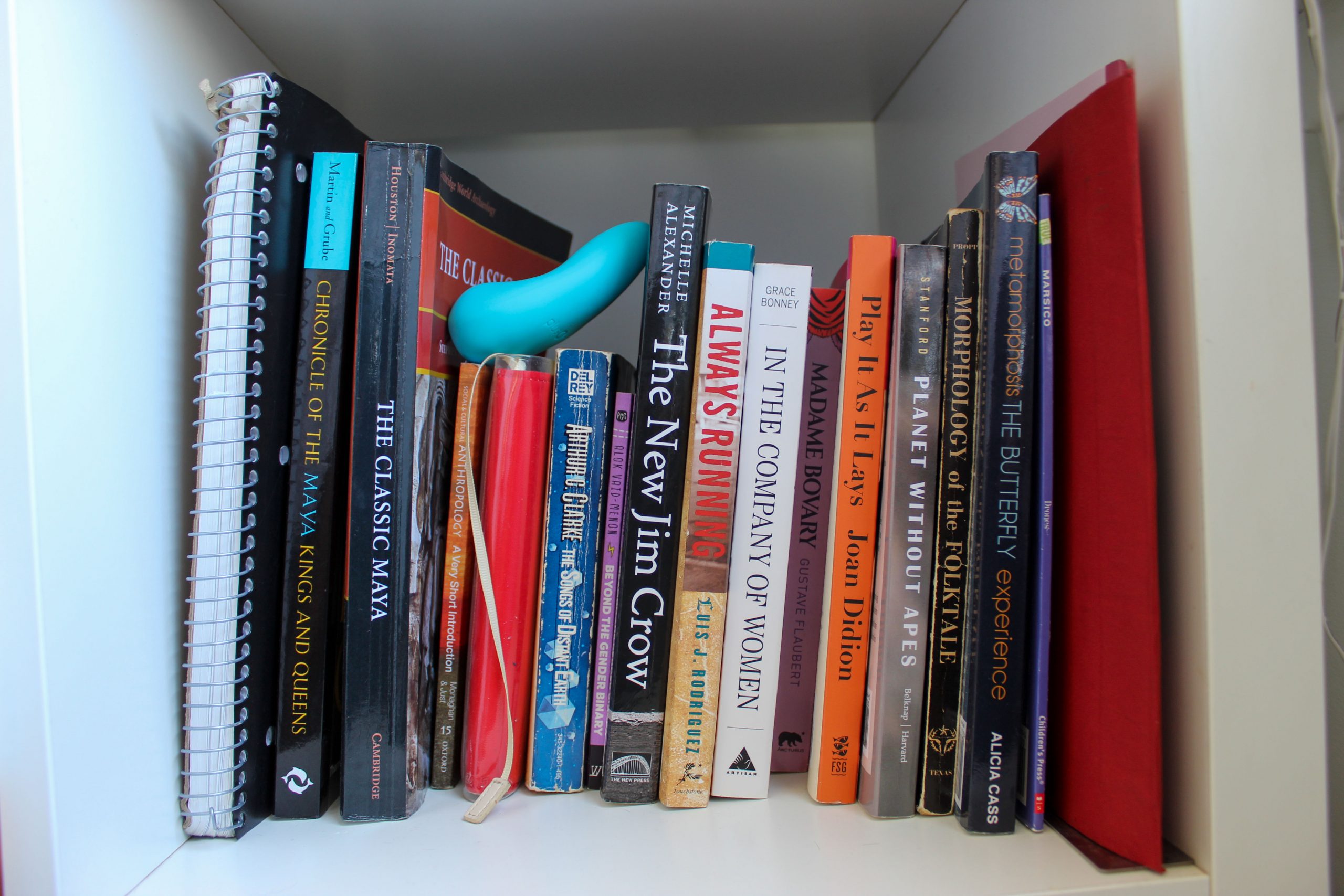

a student’s bookshelf

one of her vibrators on her windowsill

her other vibrator resting on top of some school books

“I’m hesitant to say that I don’t have a sex life, since I fuck myself very often,” J.F. said. “I’ve grown into a deeper relationship with what [it] means to have sex with myself… I also was able to make myself come without another person or without pornographic material for the first time in my entire life just a few weeks ago…. and if it wasn’t for the pandemic… that wouldn’t have been able to happen.”

And that’s where toys come in!

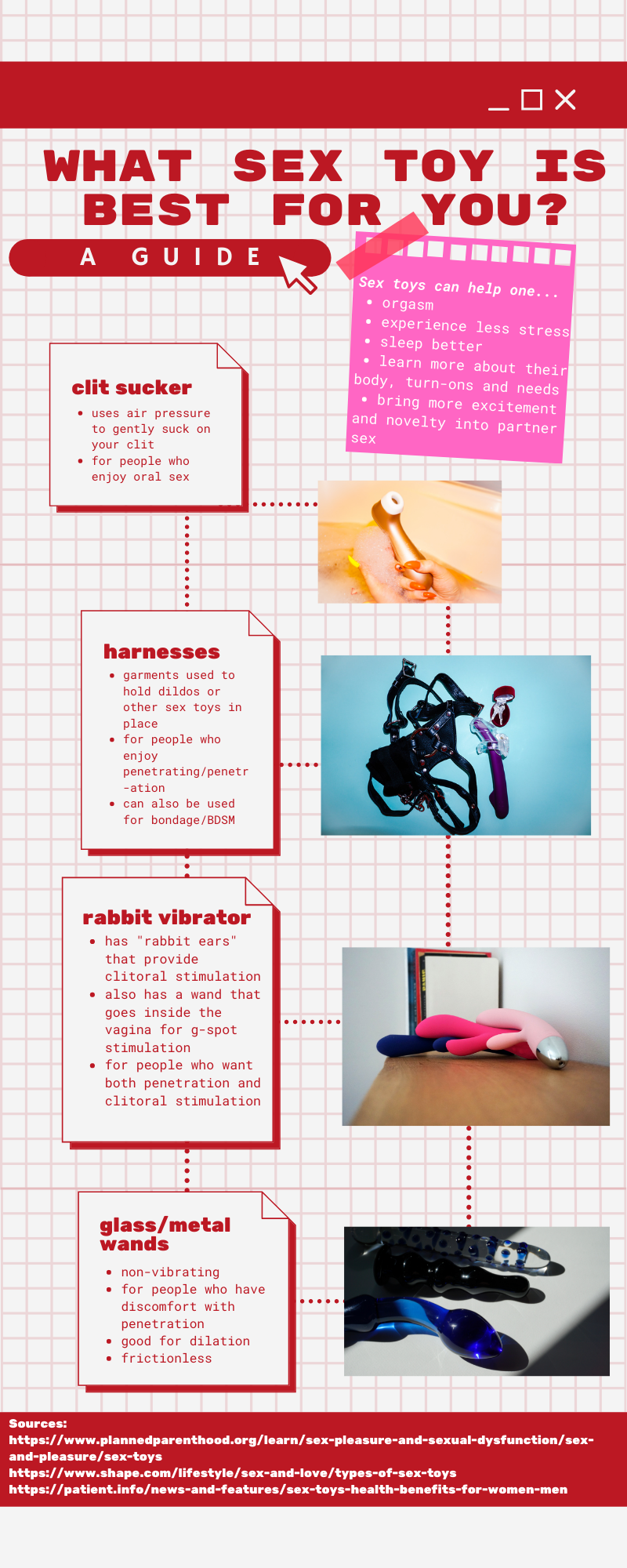

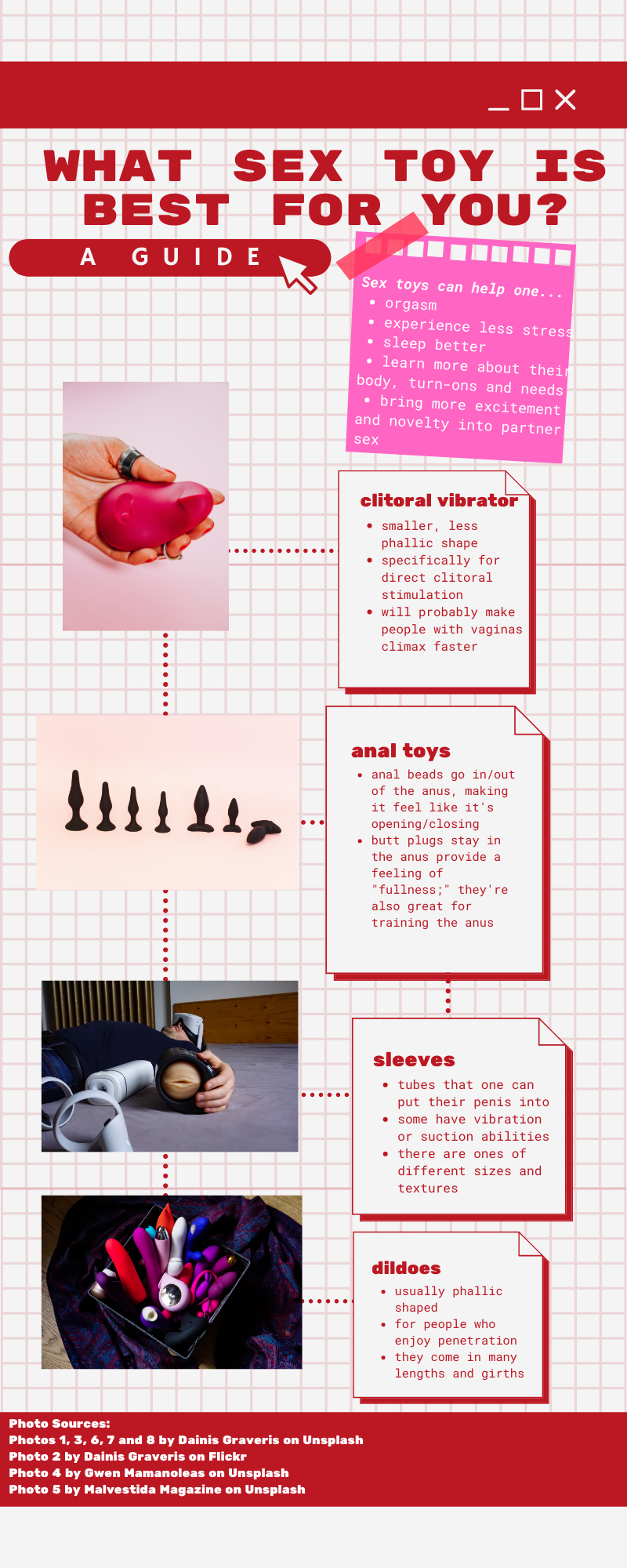

For example, J.F. has been investing in more and more sex toys for self-pleasure. Since the pandemic started, they’ve bought a butt plug, nipple clamps, a new vibrator that stimulates multiple pleasure zones simultaneously as well as a remote-controlled one that they haven’t used yet, but is nonetheless there if they need it.

“[The pandemic] has allowed me to explore the world of sex toys more and figure out what each [toy] does,” J.F. said. “Before, I just had my little rabbit wand, but now I’m buying all kinds of stuff. Sex toys have always been great, but I have a newfound appreciation for them in the pandemic.”

By using toys to masturbate—getting ready, washing one’s hands, masturbating, washing the toy after—one is creating a semblance of a routine for themself. During quarantine, a time holding so much uncertainty and temporariness and yet, inescapable boredom in which every day feels the same, getting into a routine like this can ease a bit of the stress that people—especially college students, who are on the edge of entering the “real world,” a job search, and just general uncertainty—are feeling.

R.K. spoke on the ritualistic aspect of using sex toys and while she says that she doesn’t think the pandemic really changed the way she used her toys, they’ve always been “more of an experience.”

a student’s bedroom

her bedside table and vibrator

the sunglasses case in which she keeps her vibrator

“[Using toys] makes it feel like I’m setting aside time to do this for myself versus ‘I’m here, my hands are clean, I guess we’re going to go for it,’” R.K. said, laughing.

M.H., who had just gotten out of a long-term relationship when the pandemic started, actually bought her first sex toy during this time. She said that toys were always something she’d wanted to explore or experiment with, but still she’d never really sought them out until quarantine.

“I was just relying on myself,” M.H. said. “I got a vibrator and that was a whole new world of discovery because it was like ‘damn, I really don’t need anyone after that.’”

E.L., a student at the University of Texas at San Antonio, bought his/their first sex toy during the pandemic. Not only did the toy itself change the way he/they were able to masturbate, but the time spent in the actual shop was an experience in itself.

“[When I went to the sex shop], it was so comfortable,” E.L. said. “The workers are so casual about sex, and it kind of brings down the drama of talking about it. I feel like that’s how all people should talk about sex.”

a student’s bedside table on which he has his dildos, lube, and a “you’re my person” mug

the student’s dildos

R.K. has even started to buy sex toys for her friends, which has sparked all kinds of new conversations about masturbation and exploration—conversations that they weren’t able to have before quarantine.

“For some reason, there is this distance between talking about sex that you have with other people, which is socially acceptable, and sex that you have with yourself, which is much less socially acceptable,” R.K. explained. “I think that giving my friends toys that might heighten their masturbation experiences really opens the door to us talking about our concerns or confusion surrounding it, because we all have them. Masturbation is a part of almost everyone’s lives, and yet, we don’t talk about it.”

J.F. also noticed a shift in their friends’ attitudes towards talking about sex.

“It definitely seems like the my friends feel more open to talking about sex with me, which is something that’s new,” J.F. said. “For example my best friend, who used to cringe whenever I brought up anything related to [hooking up] or sex, is now the one inviting me to have conversations about it and even telling me about their masturbation process.”

Dr. Mary Andres, a clinical psychologist, professor of clinical education at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education and human sexuality expert, credited this newly established openness to the prolonged period of time that quarantine has left us to float around in.

As people’s lives are slowing down in some ways, they’re feeling bored or stagnant. Sex toys—whether they’re used with a partner or not—could bring in some much-needed excitement, novelty and playfulness, so more and more people are taking ownership of their curiosities and exploring that world.

“[People have time], they have access, and they’re giving themselves permission [to explore],” Andres reasoned. “The thing about masturbation is that it’s kind of a solitary exploration, so some of it is like ‘do I give myself permission to go find some information that helps me [masturbate] better and then reap the rewards from that.’ That process is happening more because peoples’ lives have slowed down in some ways.”

And while A.A. and A.N., who are students at the the University of Southern California and the University of Houston, respectively, haven’t invested in any new sex toys since the pandemic started or noticed any change in the types of conversations they have with their friends, their sex lives and masturbation habits have definitely shifted.

Pre-pandemic, A.A. said he would masturbate “once every couple of days.” Then, when quarantine started, he said he masturbated more frequently, around once a day.

Contrastingly, A.N. was in a long-term, monogamous relationship when the pandemic first started. Before quarantine, the couple would have sex “about once or twice a week,” but when CDC guidelines got stricter, they could only see each other intermittently and in turn, had much less sex. Later, after her/their partner had contracted and then recovered from COVID-19, they became more distant and had sex “around once a week or every other week.” A.N.’s relationship has since ended and so not only has her/their sex life had to evolve once again, but her/their masturbation habits have as well.

Before the pandemic, she/they would masturbate “once, maybe twice a week” with a vibrator. Then when quarantine started, A.N., who has always lived in her/their family’s home, was going through a rough time with her/their mental health, felt a drop in her/their libido and started to masturbate “maybe every other week.”

“I just didn’t have it in me [to masturbate],” A.N. said. “It felt like an ordeal, and it started to feel like a chore.”

R.K. shares A.N.’s frustrations as quarantine also made her mental health ebb and flow, which led her to temporarily consider masturbation differently than she had pre-pandemic.

Before quarantine, R.K. lived in a dorm room with her roommate. Her masturbation habits depended on her mood, if or when her roommate was coming home and how often she was having partner sex, but she concludes that she used to masturbate “around once a week.”

When the pandemic first started, R.K. had to go back home and stay with her family for about six months. She would often feel “extremely” anxious and in turn, have trouble falling asleep. To ease herself into it, she’d masturbate every night to briefly clear her head of the intrusive thoughts and self hatred she was experiencing.

“[Masturbating] became one of the only things that I’d look forward to in the day because I’d get this moment of peace,” R.K. said. “But even then, it wasn’t about focusing on my pleasure. [Masturbation] was a tool to shut my brain off for a second.”

However now, R.K. is back in Atlanta, in her own apartment with her own bedroom. She can freely pleasure herself whenever and however she chooses.

“I have the opportunity to do all the things that I would want to do, I have my own space,” R.K. said. “I actually get to have my room as a sanctuary, so it’s felt a lot more like having sex because I feel that sense of total engagement with my own pleasure the way that I couldn’t when I was in a bad place mentally.”

This self-aware engagement in self-pleasure is important because there is oftentimes, a deeply ingrained shame in masturbating. A shame that intersects with various aspects like one’s culture, the way that their environment has socialized them, the media they consumed or grew up with, their family, etc.

There’s also a taboo that clings to the sale and use of sex toys. In fact, they’re still banned in some countries, such as Saudi Arabia and Thailand and even places in the U.S., like Alabama.

a student’s closet, in which she keeps her toys

her collar

her box of other toys

lingerie, a vibrator, handcuffs and another collar

Some of these students didn’t necessarily grow up with shame surrounding masturbation and toys, but there was still an element of secrecy and taboo.

R.K. smiled when asked about the ways she was raised to think about masturbation, since “no mention of sex was allowed in [her] household.”

M.H., who grew up in Pakistan, said that “[masturbation and sex] were things that were never talked about.”

A.M. was brought up as a Baptist Christian and says that masturbation was something that was “looked down upon, but somehow not discouraged.” However, he remembers that he “knew [he] had to be secretive” about masturbating the first time he did it, as he didn’t think his parents would approve, at least at that time.

E.L. never had a conversation with his/their parents about masturbation and sex, but recalls his/their older sister, who did some of the parenting in his household, “making it seem like the worst thing ever, like it was disgusting” when E.L.’s brother, who was 13 at the time, was caught masturbating. While much of this is also due to the ways his sister was socialized to think of masturbation and sex, E.L. says that the situation was “horrible.”

A.N. says that there was “no formal sex talk” with her/their family and that information about how to masturbate and use toys was something that she/they had to seek out on her/their own.

Dr. Doni Whitsett, a clinical professor at the University of Southern California’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work and AASECT-certified sex therapist, speaks on how all this taboo comes from the stigmatization of masturbation.

“In general, masturbation is very stigmatized in our society and in most societies,” Whitsett said. “There’s a continuum of punishment from those that say [masturbation] is a sin and you’ll go to hell to those that say that it’s just not okay or something you should not do.”

And though Whitsett hasn’t done research on college students’ masturbation habits and their use of sex toys during the pandemic, she says that she “[isn’t] surprised” by the rise in the sale of toys or the assumed increase in peoples’ self-pleasuring.

“People were faced with themselves, and I think that was a good thing,” Whitsett said. “I’ll bet that [the pandemic] actually desensitized some people to feeling ashamed and guilty about it. Maybe they were able to say ‘well, this is what I have to do because I’m keeping myself safe.’ Maybe they were [able to rationalize]… and use sex toys to compensate for the lack of partnership.”

Dr. Andres also talks about the novelty that bringing sex toys into partner or solitary sex can provide.

“When you’ve been in quarantine with the same person, adding a sex toy to the mix is like adding another vistor or expanding the bubble,” Andres said. “They get to share this exciting experience of discovery, and we need to normalize that and give people permission to have these kinds of safe adventures that toys are offering.”

While there’s no way to predict the pandemic’s lasting effects on college students’ or society’s consideration of sex, sex toys and masturbation, it’s clear that there has been an awakening of sorts: students are discovering themselves in a way they haven’t before, reframing their relationships to masturbation and partner sex and reconsidering their sexual needs and desires.

College students are adapting, exploring, experimenting and creating their own excitement amid the mundane that the pandemic has veiled sex and life with.

Now, we just have to see what comes next.