When Katrina Storton began working at a Target in Goleta, CA, she said it started out like any other customer service job, but with less community than she was used to. Workers at the store weren’t allowed to eat lunch together, and she only knew the people on her team.

“We were already kind of just treated like numbers,” said Storton. “But once quarantine started and corporate told us we had to start complying to certain health codes and things of that nature, it became very clear that it was the customers who were more important than the employees.”

Just a few months after she started, Storton was forced to open the store by herself. No one else came in for their shift except her manager, who she said spent the morning on the other side of the store calling other workers to see if they planned on coming in.

She was working self-checkout alone when a man demanded she scan his items for him.

“He was asking this of me while I was helping an elderly person at the register,” Storton said. “He was actually putting his fingers between me and the screen and snapping at me and telling me, you have to go scan these for me.”

Storton decided it would be easier to help the man. That’s when he demanded her employee discount.

“This man just would not give up,” she said. “He was telling me that, ‘this is America, you need to be nice to me. Shouldn’t you be nicer to me? I thought this was the land of the great’ and all this. And I just said, sir, the payment screen is right there. You can pay or you can leave. And that’s when he got really close to my face and yelled at me and told me that I had to give him a discount.”

This wouldn’t be the last time Storton dealt with an aggressive customer alone. The pandemic only made things worse for her and others across the nation. According to a study from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, customers are the second most cited reason for an increase in stress for essential workers. The first reason is an increased workload. The study describes customers as “abusive.”

“The customers were horrendous,” Storton said. “Everyone came in to buy their toilet paper and their cleaning supplies, but half of them didn’t want to wear masks, and then would harass our security guards and our front of store cart cleaners.” The Target store where she worked was one of the only stores to stay open in her area.

Storton remembers one woman in particular who she asked to put on a mask. “She said, ‘Why, nobody’s here?’ And I’m like, I’m here,” said Storton. “There’s other employees in the store. We’re people.”

But Storton said the customers didn’t treat the workers as people. She saw them throw money at cashiers, yell, try to hit workers and some even spat at her and others.

Storton said many of her coworkers were “numb” to their mistreatment. “They were just looking for hours. A lot of the people who are still working there had families and this was their main source of income and they just didn’t want to mess it up,” she said.

“There’s good interactions and bad interactions always,” said Sam Duvall, who works in a leadership position at a coffee shop in Santa Monica. She’s the person who’d come if you asked to speak to the manager. She tries to handle rude customers for the employees who work under her.

“That’s just how it is in customer service, so it’s not like I expected anything great, but the difference during the pandemic is that there’s a lack of clarity at how much we’re risking being there,” said Duvall.

She recalls a time a customer became angry because the shop couldn’t complete her large mobile order two minutes before closing.

“She just flipped out on me and she wasn’t wearing a mask. I told her to put the mask on and then after I told her to put a mask on, she called me like a whore and like all of these words,” Duvall said. “She started recording us. It was just like a whole situation and you never want to be called a whore at work.”Duvall also said her coworker thought the woman was being racist. “I don’t remember exactly what she said, I just remember my coworker saying she felt racist undertones,” Duvall said. “She refused to leave without getting my coworker’s information, even though she already had mine.”

While there’s been an outpouring of support for the health care workers who’ve taken care of patients and families during the pandemic, other essential workers haven’t had access to the same level of support or the same resources. Dr. Robyn Mehlenbeck, the director of the George Mason University Center for Psychological Services, saw this discrepancy and worked with her colleagues to address it.

“We saw a big community need and were really just trying to brainstorm how we could support our community,” said Mehlenbeck in an interview.

“Health care workers were getting some attention and some support, but not all essential workers,” said Mehlenbeck, who is also a clinical psychologist. “We decided to see if it was possible to create a phone line to provide emotional support to any essential worker, whether health care, teachers, postal workers, retail workers, anybody really who is considered an essential worker.”

The result was The COVID-19 Essential Workers Emotional Support Line which is based on a three step model. The first step is an anonymous phone line, which is open from 8:30am-8:30pm, seven days a week. Doctorate student and program director Kara Hokes trains all of the undergraduate volunteers who work the line.

“We have about 20 volunteers who received over 40 hours of training in grief, helping skills and listening skills to really just provide emotional support,” Hokes said.

Volunteers are also trained to handle intimate partner violence, suicidal thoughts, and child protective situations. “We’ve just really aimed to increase exposure and to help anyone in the community who might be reaching out,” Hokes said.

Anyone, even out-of-state residents, can call the support line for free. Dr. Mehlenbeck said people who would not normally seek out counseling have called the line because it’s completely anonymous.

However, only workers living in D.C., Maryland, or Virginia can access the second and third steps of the process, which include three therapy sessions, then 15 additional sessions after that, all for free.

Right now, the clinic is fundraising in hopes of keeping the program running for at least another year.

“We really anticipate ongoing mental health needs for essential workers even as the country starts to come out of the pandemic,” Dr. Mehlenbeck said.“Depression and anxiety rates are actually skyrocketing even as there’s hope with the vaccine.” For example, the support line is seeing an increase in calls from teachers since schools in the George Mason University area started in-person classes.

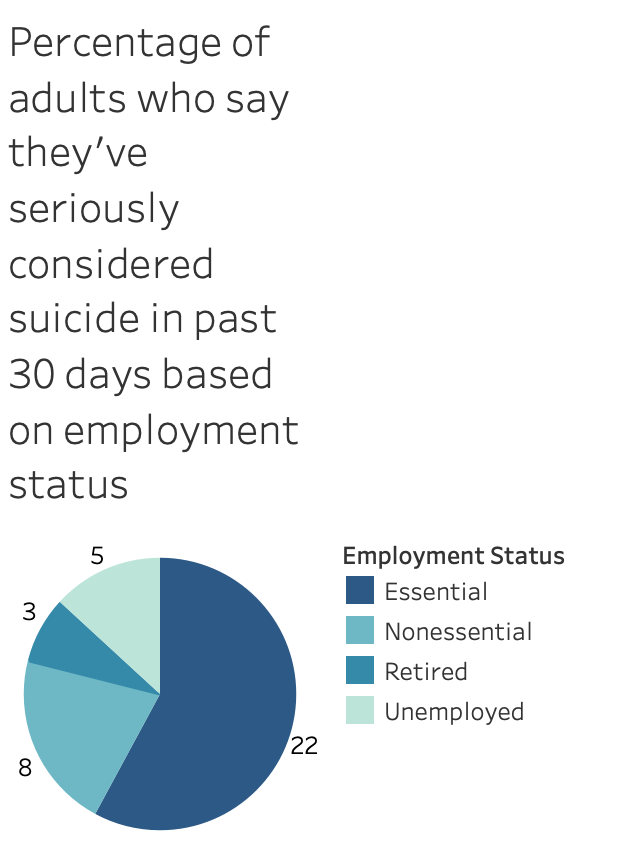

“I think essential workers are a group that have worse mental health outcomes than the average population,” said Hokes, the support line director, “because of the exposure to traumatic stress and fear of contracting the virus, because they’re not able to quarantine in the same way maybe an average individual who can work from home might be.”

Former Target employee Katrina Storton said her treatment negatively affected her mental health, and it wasn’t just the customers. “In the break rooms, there’s all these posters about free therapy and mental health and, you know, to make sure to take days off and stuff like that, but it was just all posters.”

She said the management in her store didn’t care about the workers’ mental or physical well-being. “The cleaning crew was getting really dry skin and some of them even rashes from all the cleaning supplies that they were spraying on the carts,” Storton said.

She remembers having to fight to get padding behind the registers, where workers would sometimes stand for their entire eight-hour shift. “It was taking a toll on all of us and our managers really didn’t care.”

“Then they started asking us not to wear masks and only wear gloves, and then we were asked to wear gloves and masks and then we were told not to wear gloves,” she said. “This all happened in a month’s time. Every shift I was there, there were different rules in place. You couldn’t keep up with it.”

Storton said her store didn’t provide or require masks at the beginning of the pandemic. When corporate told them they had to, her management cut up T-shirts to give to the employees.

She also said her store didn’t enforce social distancing or health guidelines. “Whenever corporate officials would come in and check on our store to make sure we were distanced and everything, they would put on a big show and make sure we were all washing our hands and wearing our masks and doing everything properly and super cleaning,” Storton said, “but the second those corporate people left, our managers just didn’t care and were being rude to us again.”

She was even trained as a manager, but never officially promoted. “I was being given all of these responsibilities without the pay and without the title,” she said. “I think they were just exploiting that people needed work and that everything was closed and Target was really the only thing open.”

Storton eventually left the company for her health. “I couldn’t go back and I just don’t want to risk it anymore,” Storton said.

Target did not respond to a request for comments for this story.

Coffee shop manager Sam Duvall said her job negatively affected her mental health, too. Aside from the problem customers, she’s also working full-time while also enrolled as a full-time college student. “I usually do three hours of schoolwork after a full day at work,” Duvall said. “It’s hard to concentrate when you’re already exhausted.”

The COVID-19 Essential Worker Emotional Support Line is preparing for the effects of the increase in stressors essential workers are facing. “There are some pretty well documented impacts of sustained high stress,” said Mehlenbeck, director for the George Mason University Center for Psychological Services, “that includes some very severe physical health impairments, headaches, migraines, there’s cardiac effects…”

Hokes, the program director for the support line, said the increased stressors have caused an increase in diagnosis and substance use. “People are having to cope with difficulties that they might not have coped with before,” she said.

Another worrying effect of high stress is sleep disturbance. “Once you have sleep disturbance, coping becomes very difficult,” said Mehlenbeck. “That is a double whammy for many of our essential workers. Lots of our social workers don’t work regular work hours either, so their sleep is naturally shifted or off.”

If you’re worried about how to help an essential worker in your life, Mehlenbeck said the best thing to do is ask them what they need. “It could be a walk outside,” she said, “it could be getting outside to a park, away from the house, away from work and away from people.” She also recommends reaching out to a local clinical psychology clinic for free or reduced therapy and counseling.

“I just think everybody needs to support each other and we’re just really proud that we could be one more resource for people and take a little barrier away,” Mehlenbeck said.

Duvall is hopeful that overlooked essential workers like Storton and herself will be able to stand up for themselves in the future. “A lot of people are bringing up the whole customer is always right thing and how it’s not really fair,” she said. “I don’t really know how long it’s going to take for that way of thinking to kind of turn around, because that’s been a way of thinking for a while, but I feel like with this generation, like we’re kind of being like, that’s not really okay.”

For essential workers in California, Covid19CounselingCA offers short term counseling for free through therapists who volunteer their time.