Black Trojans ‘fight on!’ in midst of a global pandemic, protests, racial injustices & scandal

By Cameron Antoine-Dillon

To understand how we arrived at a ‘disconnect’ as Black Trojans is to understand the deep-rooted institutional flaws tied to the household name. The very two reasons students, in general, chose USC is: the Southern California atmosphere and because it top 25 most prestigious schools in the nation. A win win!

In reality, ‘selective programs’ and ‘USC expansion’ are fancy euphemism for the university’s history in gentrification and biased admissions.

In 2018, the beloved black-owned Lil Bill’s bike repair shed, where all Trojans got their tires pumped and bike adjusted, was removed after the university threatened to bulldoze it down since it was an illegal business one USC-property. The shed has been apart of the community for 40 years. Owner Aaron Flournoy, was told to relocate on the outskirts of campus, after his service was replaced by the high-end Sole bike shop, an addition to the $600 million Village renovation.

Like all business transactions, the university blindly ‘expanded’ in turn for luxurious new restaurants, residential living, retail and grocery stores for its students and community. At this time, USC’s $315 million newly seated Coliseum, alongside the new billion-dollar Rams stadium in Inglewood (2020) were hailed SO-Cal entertainment hubs, while widely drove out native Black & Latino communities from their homes, businesses, and jobs.

Undoubtedly, a big part of USC’s elitism lies within athletics, which has prioritized its infrastructures. Yet within these programs, are undertones of discrimination and gentrification.

Across the nation, Black athletes of revenue-generating sports play under white coaches and owners. Many argue: they receive education in return for athletics, how is it not fair? In perspective, the profit USC coaches like Helton and owners received from its multi-billion dollar revenue generating sports, are off the backs of Black student-athletes some of which are still hungry, homeless, and mostly all can’t control their image or profit due to NCAA regulations. They are ‘recruited’ even with knowledge of their socio-economic and educational disparities, for a chance at the American dream: faith, family & football.

That is a new system for our 400-yr condition.

Only 2% of student-athletes get selected to the professional level, according to the NCAA.

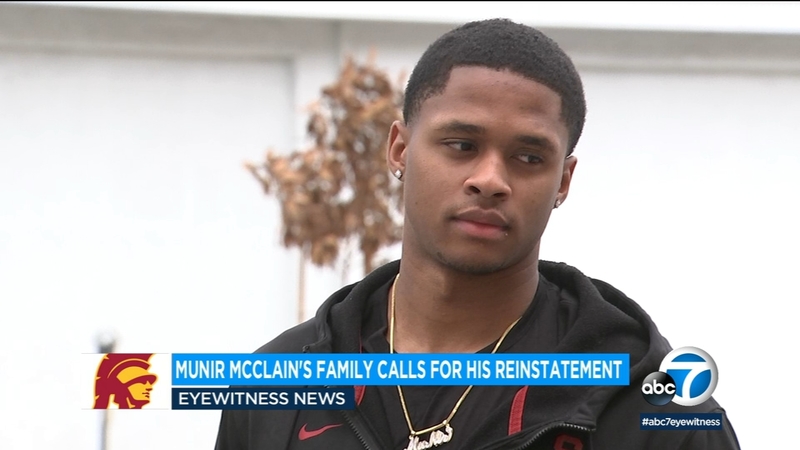

In September, racial climate in USC Football community was fusing. Promising wide-receiver Munir McClain, a Black sophomore, was interrogated at his apartment by federal agents on suspicion of fraud. The university suspended him indefinitely, before the trial was concluded. While protests broke out in his defense, Munir and his brother already packed their bags back East. This cost him his ticket to the next level.

In this way, athletic programs at PWIs, are perpetuating gentrification through profiling and biased policies on its Black athlete. In response, a new wave of Black prospects are shying away from top programs like USC and have considered rebuilding athletic programs at HBCUs instead.

Around JMC, Black athletes are still the clear majority in the school’s most revenue generating sports: football, basketball & track. Yet, beyond the walls of JMC, these athletes comprise of the very small percentage of the rest of Black Trojans.

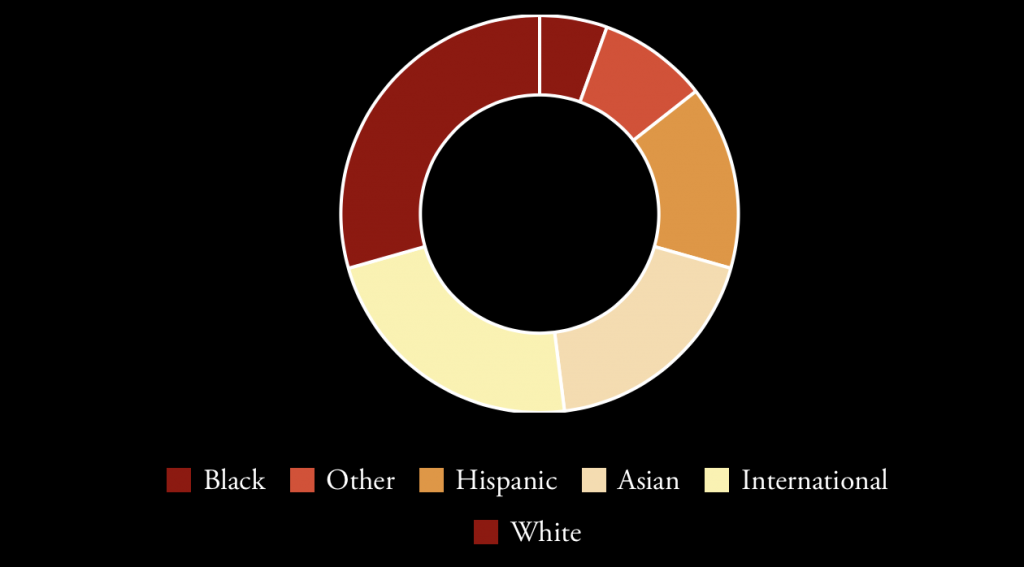

In the 2020-2021 USC school-year, African Americans remain the most underrepresented ethnic group, comprising only 5.5% of USC’s student body.

2020-21 USC Student Demographics

Willie McGinest, class of ’94 football legend, 3x Super Bowl Champion, and now NFL Network’s analyst, demands changed at his alma mater. “Times have changed. We’ve got to do a better job of allowing minorities to be on campus,” says McGinest. He adds, “I’m not saying lower the restrictions or values they have in place that makes SC what it is, but those are the same things in place that keep us off campus.”

One restriction McGinest may be referring to is admissions.His college experience of “diverse brotherhoods”almost thirty years go is evident of affirmative action.

Today, Affirmative action would have mandated admission of historically excluded groups in USC’s programs, and offer “outreach programs, targeted recruitment, scholarships and financial aid awards, retention and matriculation programs, and programs that encourage and support the attainment of advanced degrees” (USC Dornsife).

Instead, USC’s external gentrification of a historically Black South L.A. has infected the internal systems of admissions, curriculum, and extra-circular spaces, contributing to nonexistent feel of Black educational or cultural spaces and Black familiarity overall.

Greedley Harris, the director of Black Culture and Student Affairs (CBSA), is honored to partake in a ‘Black Trojan history’ but is still developing to congregate both undergraduates and graduates.

“Foremost retaining Black faculty and representing Black students is a huge institutional gap here. I think my office is helping that. I along with Black student leaders organize communal meetings and events for a familiar group of mostly upperclassmen, but another focus is to bring in incoming students to navigate college at a pivotal time of transition.

Even with the spaces for cultural gatherings, Black students still don’t feel seen from the institution at large. Instead, ‘diversity and inclusiveness’ is an perforative act for pamphlets, websites, and mission statements.

Ronald Spencer Boras, a senior Thorton student, chronically attends CBSA and Brothers Breaking Bread. Though he got involved in such groups, he felt compelled to continue Black culture on his own terms. As an artist, DJ, producer, and event coordinator, most Black Trojans know him as “Ronnie Quest.”

‘Quest’ has thrown numerous Black USC functions: Thriller Part I-III & USC vs UCLA, and performed at USC’s student art-festival GearFest. “Rod, Lux and I really just did it connect Black people and promote our label NPI. It’s one of the few times we get to listen to music we want to listen to, have the drinks what we want, and dance” says Boras.

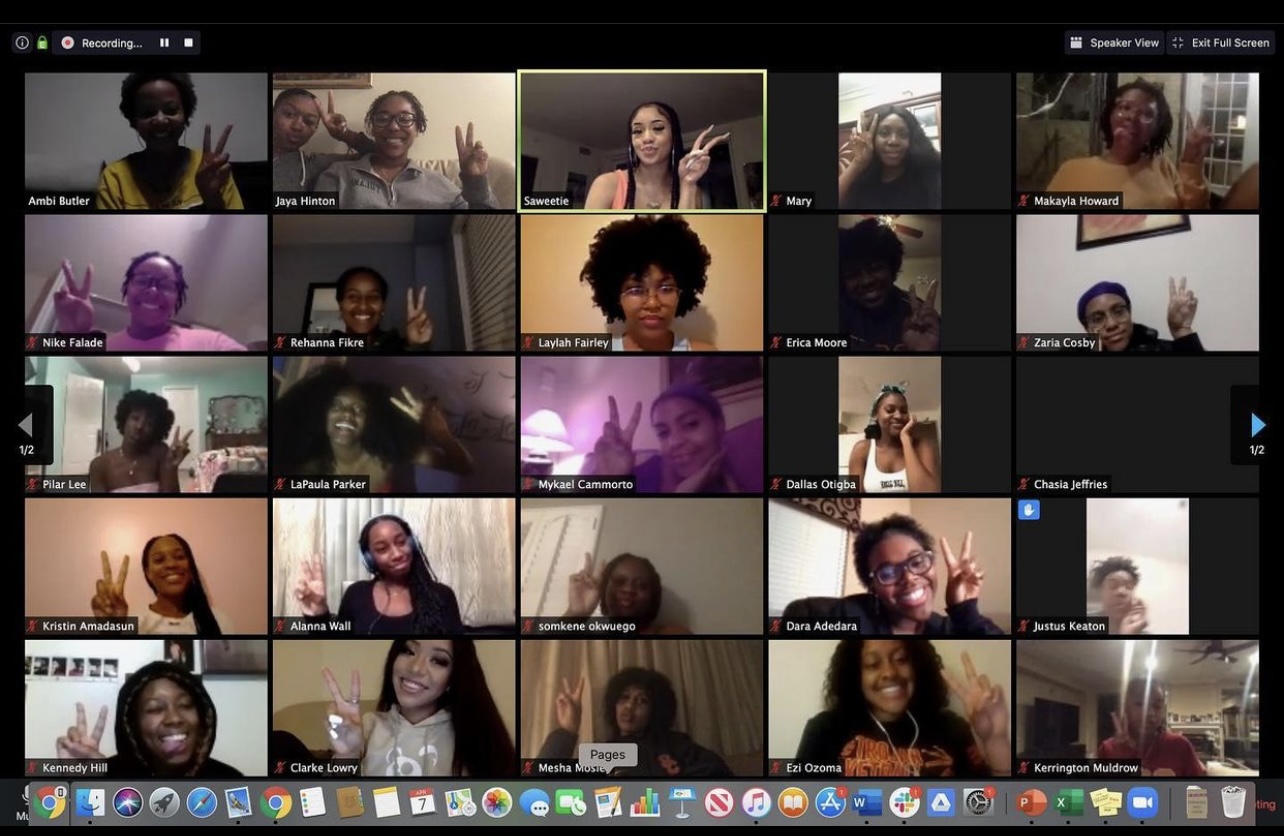

Despite his success, the “lack university support” has frustrated Boras. “You know they do not claim these Black creatives and artists like Saweetie, 24kGoldn and [Pure] Lux until they make it. I witnessed coaches bring in recruits to show them the culture at usc, but this isn’t the reality. This is a show we probably get to do 2-3 times a year, meanwhile DPS shuts down all of our real functions,” remarks Boras.

This past year alone, support was what a lot of Black students needed. The weight of racial injustice, a global pandemic, and life itself hit while still juggling the demands, though more flexible, of a 12 to 18 unit workload.

A quick recap of this year: Kobe died, people were deathly sick that face masks and cabin fever became a norm, sports was cancelled, campus was shut-down, George Floyd was murdered in broad daylight, & Black people were beaten and jailed for peaceful protests.

The last thing we needed to do is turn on our cameras, show face to engage and participate for hours on end for zoom etiquette.

Jamie Dubose, is a Black freshman Annenberg student by day and tv personality & entrepreneur by night, who especially struggled transitioning online into her first year.

“It was hard to stay motivated online. everything felt optional but it isn’t. I feel like everyone, even professors complaining ‘this Covid, we need a break,’ because not everyone is there mentally. The university could do better being more lenient with students, because this is a situation no one prepared for,” believes DuBose.

Even much needed wellness days, after the overwhelming news of Covid and racial injustice, were “catch up days on assignments” rather than focusing on our mental health.

Yet, Dubose found a balance of when to recharge and when to react. Like other college students, she has used her social media platform to advocate for mental health and share her experience at local Black Lives Matter protests.

On campus, Black USC students led their own Black Lives Matter protests, one in spring and the other fall semester. In the wake of George Floyd, other institutional issues unfolded simultaneously with the George Tyndall sexual assaults, VKC’s Eugenic ideologies, and then the Munir Mcclain scandal.

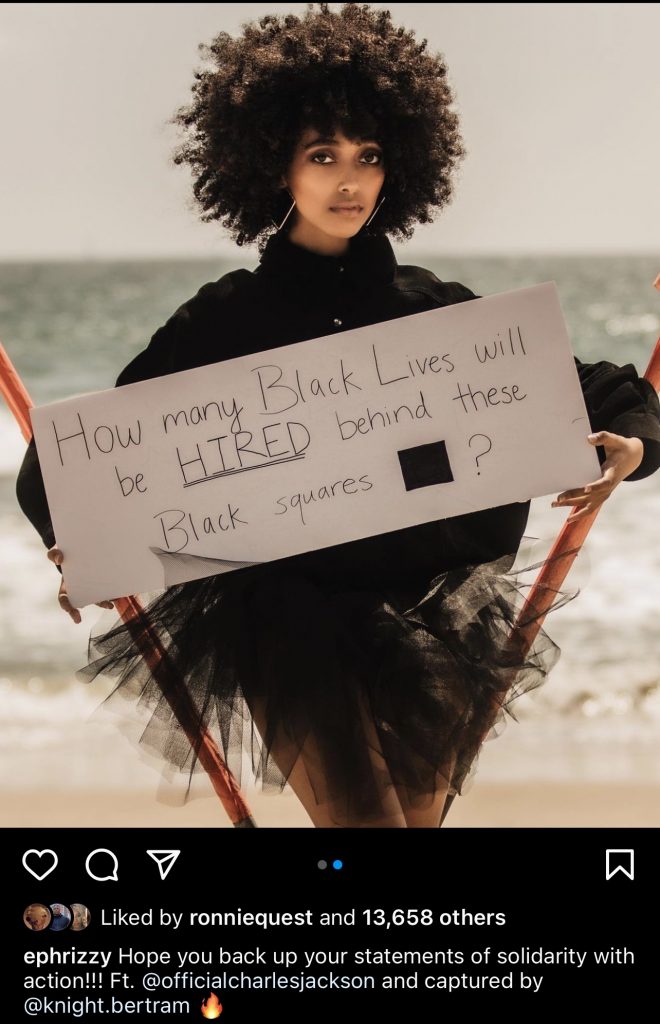

Here, Jephtha, a stand-out student, recited his own poetry and led powerful affirmations through his megaphone for hours. The students gathered and marched until the Coliseum. Whether at the protests or on social media, Black USC students also used symbolic art and posters to speak volumes.

Students extended several invitations to President Folt to join and support the student-body through tagging her social media handles.

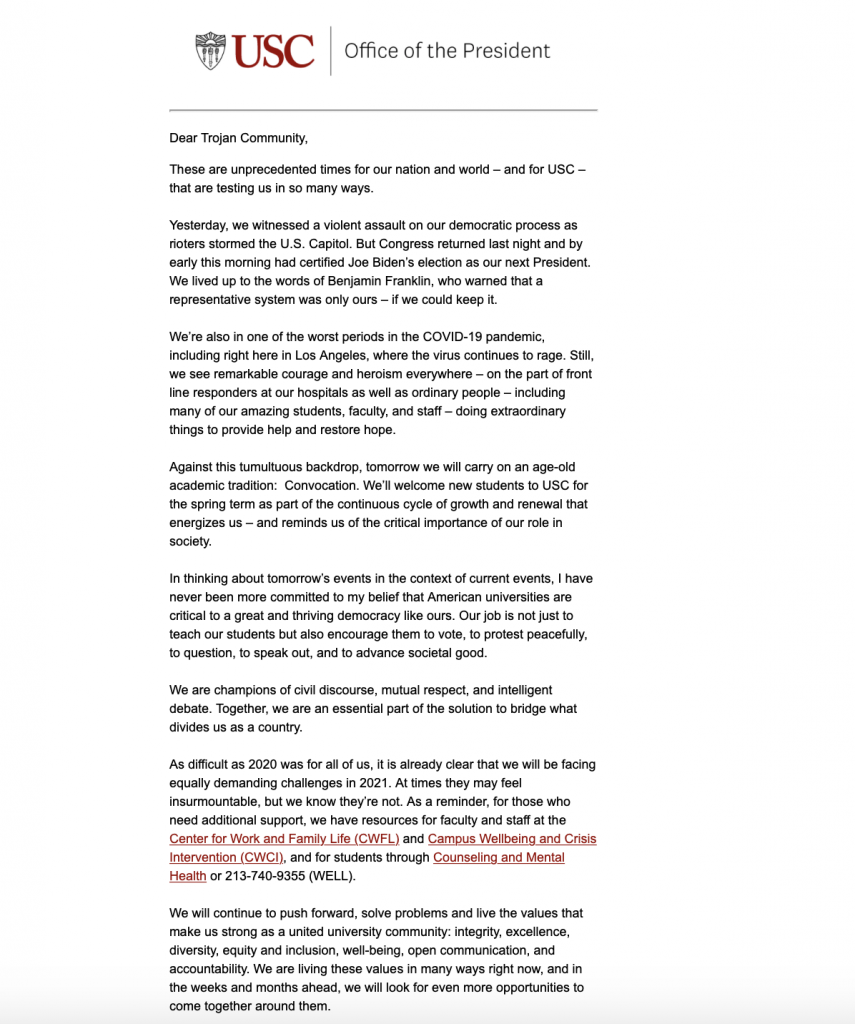

President Folt was nowhere to be found. Instead, Folt’s allyship was a series of untimely, underwhelming statements. Her rhetoric commonly used “support” “allyship” “will not tolerate racism” “horrific events” “unprecedented times,” often linking crisis or mental health hotlines.

Many felt our leader, our institution, our home away from home, had missed an opportunity to actually support the Black community happening on their own grounds.

Since then, the university has issued several new policies in electing new (DEI) and (BDEO) board members, (CBA’s) Pilot Conversations on DPS policing, steps on reporting discrimination and racism, and celebrating Black history month.

In the midst of Black students’ pain, anger, and disappointment with USC, they collectively worked in solidarity––ironically a time in which they were physically distanced, yet emotionally and culturally interconnected.

Last semester, the Black Student Athlete Association was formed under current athletes: Anna Cockwrell (T&F), Joy McArthur(T&F), Jalen Mckenzie (FB), Ben Easington (FB), and Candice Denny (VB).

It became a platform for such athletes to hold dialogue about social issues, contrary to the Shut & Dribble mantra. Their organization pushed action from the Athletic Department to stand with Black Lives Matter movement and host various compliance meetings and interviews.

A major demonstration of support was the release of the 2021 student-athlete backpack. Each year, the student-athlete council designs unique backpacks, down to logo, stitching, compartments, and colors. This year was a clear stance with BLM and LGBTQ communities.

Earnie Sears III, a 5th year track athlete, was proud of his teammates for not only for a breaking national records, but also barriers in terms of athlete activism and Black voices at USC.

However Sears III has witnessed athlete’s stance echo commonly overlooked Black students’ voices, but “[doesn’t] necessarily think it’s [Black athletes or people’s] job… to educate others on what we’ve gone through” says Sears III. Instead, “we can make it a priority to teach at some point in our lives and allow them to learn,” he raises.

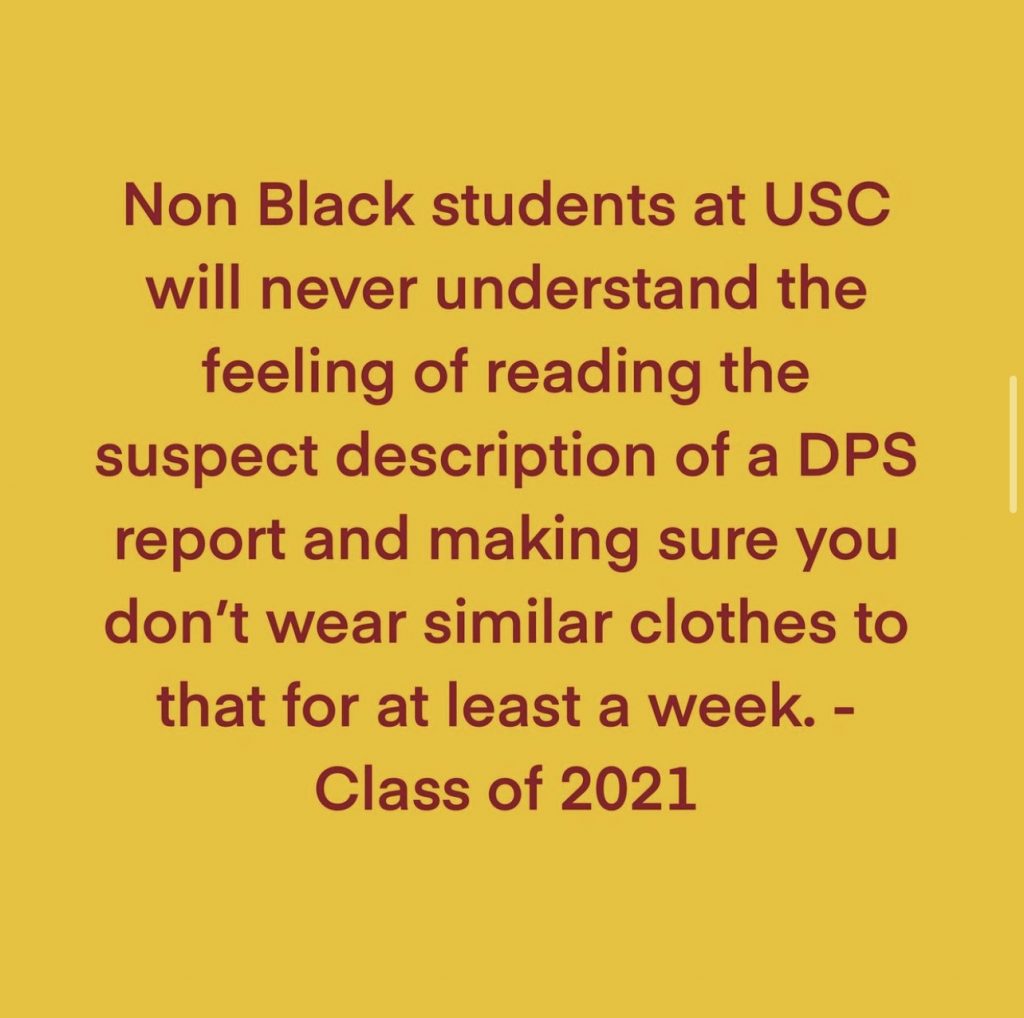

Other spaces like @black_at_usc expose have done just that.

Racially horrific and insensitive experiences of Black Trojans are posted anonymously. The 12.2k followings led to a chain of reposts, dialogue in the comments and amongst university leaders. USC community was watching and listening to our testimonies.

Some posts read:

“Being Black at USC means watvhing those from my South LA community get paid minimum wage to serve as ‘security ambassadors’ in places like Greek Row or serve food at Carol Folt’s inauguration. Inequality runs deeps. -Class of 2020”

“Non-violent Black parties getting shut down with LAPD cars, LAPD helicopters (with lights on) and DPS. -Class of 2015”

“A guy I thought I was friends with (freshman year) wore blackface to a Signma Chi Jungle Party. Everyone laughed. -Class of 2014”

For the first time, in a long time, it seemed the USC community was listening to our testimonies. Many said their white peers sent random “hey, just checking-in” or “I’m sorry if I ever” messages.

Whether it was a projection of white guilt or evidence of newfound education, it still worked.

The 553+ posts was really our confirmation that racism, gentrification, & scandals on campus were not a few ‘isolated events.’ Institutional trauma was here, real, and exposed.

Somehow in this web of institutional injustices, the former “feel of nonexistence of Black educational or cultural spaces and Black familiarity overall” was compressed. We were no longer the segregated group of Black athletes to Black students to Black faculty & staff.

At this moment the Black Trojan Family was apparent.