One family’s story of health care, homelessness and hope.

by Nate MacKay

My eyes widen as our car turns into the driveway. I barely recognize the figure waiting to greet us. His beard is bushy and unkempt, his hair tousled in a dozen directions. His yellowing fingernails, with dirt under at the quick, extend almost three inches and growing into a sharp point, like the talons of an eagle. The stench of weeks old sweat greets me before he has the chance to say a word.

That jarring day in July 2019 was the first time my parents, my sisters or I had seen my uncle Kenny Butler in over six years. It marked the beginning of a consuming family saga with Kenny at the center. Hundreds of homeless nights. Months of unraveling a medical mystery in a health care system that is frequently expensive, confusing and tedious. Years navigating a network of complicated social welfare programs to find suitable shelter, food and medical care. I have struggled with how to tell Kenny’s story, since his condition is such that he can’t fully comprehend or explain it himself. But his story is now so woven into my family’s life, I feel compelled to tell it.

From Kansas City to Reno

Kenny was 41 the day we found him standing in our driveway. He is my mother’s brother, the seventh of nine children. He was born and lived most of his life in Reno, Nevada. In 2013, Kenny, his wife Angela and their four children moved to Missouri, where Kenny had a new job. After the move, his contact with family members in Reno was minimal.

Rumblings about Kenny behaving bizarrely began in spring 2019, when Angela told some family members she thought Kenny might be dealing with drug addiction. She said Kenny refused to bathe or brush his teeth, slept on the couch for most of the day and lost his job in October 2018 for repeatedly calling in sick and misusing company credit cards.

In May 2019, Kenny began reaching out to my mom and his other sisters in a group message, saying Angela kicked him out of the house and he needed money for a hotel. My mom and her sisters took turns over the next few days paying for Kenny’s hotel stays in Kansas City.

“Every day that he’d send a message, he’d say, ‘Please, just one more night in a hotel because I have an interview [for a job] tomorrow,’” my mother said. “The next day, it was the same message over again. It was almost like he was just pressing copy and paste.”

As the days passed, my mom said she and her sisters found the identical messages increasingly unsettling. In an attempt to compel Kenny to seek professional help, they decided to try a “tough love” approach by forcing Kenny to sleep in a Kansas City park instead of a hotel.

That night, he sent dozens of messages requesting another hotel stay. He said there was a tornado coming and that he saw a person carrying a dead body through the park, among other frightening stories that his sisters interpreted as a sign he was either under the influence of significant drugs or having a psychotic event.

After staying the night in the park, Kenny finally went to a mental health treatment center in Kansas City. They found no drugs or alcohol in his system (his wife later told family she had never seen him under the influence of any substance). Because he wasn’t suicidal, the only inpatient treatment options were voluntary; Kenny refused to stay. Angela would not allow him back in their home, so he returned to the park.

Another sister paid for Kenny’s flight from Kansas City back to Reno.

Kenny spent his first two weeks in Reno living with his nephew in a week-to-week rental. The nephew would return home from a 12-hour shift to find Kenny in the exact same spot, having eaten much of the food in the apartment. The nephew found new living arrangements and the week-to-week expired. Again, Kenny had nowhere to go. He texted my mom, asking to stay at our house. She told him it was locked, but that we’d be returning from vacation later that day. As we pulled into the driveway, Kenny was there waiting.

The Search for Medical Answers

Though it had been six years since she’d seen him in person, my mother said she could tell Kenny was strikingly different.

“It was like half of his brain was shut off,” she recalled. “This is Kenny’s body and Kenny’s face and some of the stories he tells are familiar stories. But it’s not his voice, not his personality.”

She likened him to a robot, noting the only sign of emotion he exhibited was laughter, which often came at inappropriate times. When their father unexpectedly died, my mom said she and her sisters informed Kenny, expecting he’d exhibit some grief. Instead, he chuckled and asked them to pay for another night at the hotel.

My mother also thought it was odd that a husband of 20 years and father of four shed no tears after being kicked out of his home and separated from his family for nearly four weeks.

In the three days Kenny lived on the couch in our living room, my mom noticed he slept up to 20 hours of the day. The only got up to eat, and he craved sugary junk food. He refused to practice basic hygiene. Once, when told he couldn’t stay if he didn’t shower, she said she felt relieved when he went into the bathroom and turned on the water. But when he emerged, he’d only splashed a little water on his face.

He repeated the same violent, blatantly untrue stories about witnessing murders and seeing the Abominable snowman or Bigfoot. His voice was so casual when he recited his tales, it sounded like he was describing the weather.

In our extended family’s plentiful experiences with substance abuse and depression, this was unlike anything we’d ever seen. My mom began a quest for medical answers.

The first hurdle was that Kenny moved states. Though Medicaid is often perceived as a federal program, it is administered by the state government. Because of this, Kenny had to be enrolled through the state of Nevada. The process required hours of paperwork and weeks of waiting. When Kenny was finally approved, his options under the program were limited.

Chaplain Timothy Mikes of the Reno-Sparks Gospel Mission, an emergency homelessness and addiction recovery shelter, told me mental and neurological health issues present particular challenges in the Reno area.

“Nevada is horrible when it comes to mental health for its residents and there really aren’t any resources out there for people who are suffering,” Chaplain Mikes said. “The resources that are there are very hard to get, especially with Medicaid.”

According to the organization Mental Health America, Nevada ranks 47th in the United States in terms of mental health care access.

Our family’s experience quickly confirmed that fact. Of the few places in town, many had months-long waiting lists or did not accept Medicaid. Exacerbating the problem was that anytime Kenny had a consultation with a doctor, he told them—and really seemed to believe—he felt fine and did not need help.

“Each and every place would be very helpful and kind to turn me away and say they couldn’t help him, but they’d give me a list of other places I could try,” my mother said.

On recommendation from another dead-end doctor’s office, she took Kenny to Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services (NNAMHS), a state-run inpatient and outpatient facility. When they arrived, the doctor they had an appointment with had called in sick. My mom recalled standing behind Kenny with her hands in a prayer position and mouthing to the girl behind the desk to please not turn them away. The receptionist noticed her silent plea and massaged the schedule.

NNAMHS recommended weekly counseling with a psychologist. During the solo appointments with the counselor, Kenny routinely left the room every five minutes to get a drink or use the restroom before returning. The doctor got permission from Kenny to speak to my mother about the appointments afterward.

During this time, my mom began doing her own research into Kenny’s symptoms. She said she asked the doctor about schizophrenia but was told it was unlikely because symptoms of schizophrenia typically begin earlier in life. She also kept coming across types of early-onset dementia that manifested through behaviors similar to Kenny’s. When she brought that possibility to the psychologist, she said he told her Kenny was too young. My mother wanted the doctor to conduct cognitive testing or recommend some type of brain scan, but worried about rocking the boat, as she and the doctor were getting frustrated with each other. He expressed skepticism that an MRI would show anything definitive.

“I always got the impression that I didn’t know what I was talking about, that he was the doctor and that none of my Googling was helping the situation,” my mom said. “I was always afraid to question. And I was trying not to be too pushy because everyone was doing me these quote ‘favors’ by seeing Kenny anyway.”

After weeks of making no progress through traditional therapy, the doctor finally conducted cognitive testing on Kenny and shared with my mother that the results were shockingly low. Still, he suggested this was evidence of a learning disability Kenny had lived with his whole life without anyone noticing, and the effects were heightened by a stressful depressive episode.

My mom and Kenny’s other sisters all expressed skepticism at the possibility. They recalled Kenny was an average student who took some challenging courses in high school and attended college.

But Kenny could not see a neurologist or different specialist without the referral of a primary care physician. My mother had been calling around for primary care appointments for Kenny for weeks, placing Kenny on waiting lists or getting turned away because the offices did not accept Medicaid.

When the Alma Clinic had appointments available and accepted Medicaid, she said it felt like a sign from God. Alma is Kenny’s middle name. Rooted in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, faith and prayer had become integral to our family’s endurance through the mind-numbingly long months of confusion and fear, particularly for my mom. Her voice crackled with emotion describing how the nurse practitioner treated Kenny “like a human being” despite his hygiene and behavioral oddities and was unafraid to touch him or talk to him the way she would with any other patient.

The primary care physician granted what my mother was quietly hoping for: an MRI referral.

Kenny underwent the MRI in November 2019, four endless months after arriving in Reno. My mom said it felt like another small, heaven-sent blessing that Kenny kept still for the imaging, given his impatience.

The MRI results showed moderate shrinking of the frontal and temporal lobes of Kenny’s brain. The radiologist’s report suggested two causes of the degeneration: schizophrenia and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). My mom mentioned both these possibilities to the clinical psychologist at NNAMHS, who dismissed the hypotheses.

“It made me feel vindicated and relieved,” my mom said about the MRI results. “That we had noticed all those changes in him wasn’t just our imagination, that there were things really going on.”

But the relief was short-lived, as the next step in the process loomed. Kenny needed a neurologist to read the MRI report and recommend a diagnosis, but most in the area had six-month waiting lists.

My mom felt hopeful when a neurologist who had recently begun his own practice had an opening in December 2019, a full month after the MRI was conducted. But even that appointment ended in confusion. The neurologist seemed unfamiliar with frontotemporal dementia and said he was hesitant to affirm it as a possible diagnosis. He suggested they conduct another MRI in two years and compare scans then. The idea of waiting two more years was devastating.

It wasn’t until May 2020 that a neuropsychiatrist confirmed what my mom had long suspected: Kenny has behavioral-variant FTD. The diagnosis came 10 months after Kenny arrived in Reno and 18 months after the severity of his symptoms cost him his job in Missouri. Undoubtedly, his symptoms escalated in Missouri for months, even years before the job loss.

What exactly is FTD?

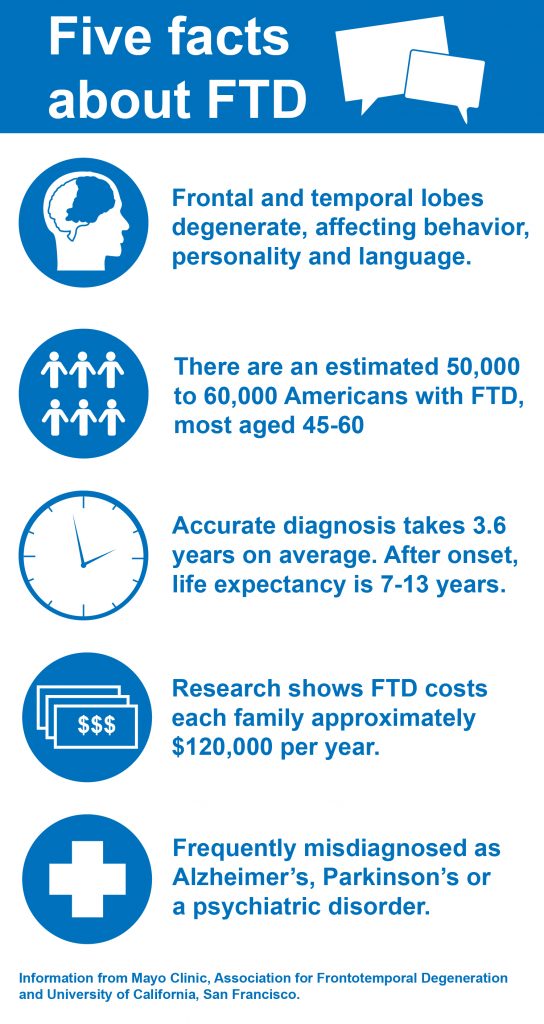

According to Mayo Clinic, FTD is “an umbrella term for a group of uncommon brain disorders” that cause the frontal and temporal lobes to shrink.

The word “dementia” often calls to mind Alzheimer’s and diseases primarily affecting memory. Matt Ozga, a representative from the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, explained that FTD affects “the personality, the behavior, the language ability.”

Symptoms of behavioral-variant FTD according to Mayo Clinic include “increasingly inappropriate social behavior; repetitive compulsive behavior; lack of interest (apathy), which can be mistaken for depression; a decline in personal hygiene; and changes in eating habits, usually overeating or developing a preference for sweets and carbohydrates.” Kenny exhibited each of these.

“The behavioral variant one is particularly insidious,” Ozga said. “Because, aside from the obvious performance decreases that come with having your brain literally deteriorating in your head, there’s also the lack of impulse control among people with FTD.”

Ozga explained that this impulse control can result in people with FTD losing their jobs, making inappropriate statements and doing things “that could be disruptive to their neighbors, to their communities.” He said this creates a particular challenge for caregivers, adding, “Anecdotally, we hear things about people [with FTD] getting sort of passed around from relative to relative.”

The difficulty my family encountered finding a diagnosis for Kenny is also common, according to Ozga, particularly because FTD can only be definitively diagnosed post-mortem via autopsy. People dealing with the disease must rely on neurologists astutely recognizing behavioral-variant FTD symptoms.

“It’s a relatively obscure disease. And it’s way, way, way more common for a doctor to see some of these symptoms and say it’s depression, or it’s some kind of mental disorder—bipolar, perhaps schizophrenia,” said Ozga. “Sometimes it’s even as simple as the doctor saying it’s kind of like a midlife crisis.”

From Missouri to NNAMHS, Kenny’s symptoms were misidentified, even dismissed, in this same way. For people of color, there are added barriers of discrimination.

Because FTD is a lesser-known, progressive disease which often onsets earlier in life, Ozga said common emotions surrounding condition include “grief, overwhelm, isolation.”

“People with FTD and their loved ones often feel like they’re on an island, that there’s no one else out there who understands what this disease is,” Ozga said. “People who have loved ones with FTD… start to mourn for the person that their loved one used to be. It can be extremely hard because you’re mourning someone who’s still alive.”

Additionally, many families are financially unprepared for FTD’s costs.

“The economic burden on families who are dealing with FTD is around $120,000 a year, which is basically twice the cost associated with Alzheimer’s,” said Ozga. “It’s an incredibly expensive disease.”

According to Mayo Clinic, “there are genetic mutations that have been linked” to FTD, but over half of people with FTD have no family history of dementia. In April 2021, genetic testing confirmed Kenny does not have one of the genetic mutations, though there are two more mutations for which he still must undergo testing.

The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration says FTD is a progressive disease for which there is no known cure. The average life expectancy after the start of symptoms is 7 to 13 years. For information and support, visit the association’s website or call their helpline at (866) 507-7222.

The Bare Necessities

In tandem with the year-long pursuit of a medical diagnosis came a struggle to get Kenny housed, fed and clothed.

During those three days in July 2019 when Kenny was still a virtual stranger sleeping on our couch and we had no idea what was happening with his brain, I remember feeling deeply uncomfortable. His penchant for reciting disturbing stories, his refusal to abide by any standard of personal hygiene and the fact that the only place for him in our modest home was the couch made it clear it was an unsustainable solution for him to stay with us.

My parents decided that a homeless shelter was the best option. My mom still feels tremendous guilt and broke down in tears recounting the day they packed some granola bars and bottled water in a backpack and dropped Kenny off at the Volunteers of America Homeless Shelter in Downtown Reno.

“It broke my heart because this was my brother and I’m telling him I have to take him to a homeless shelter, and he’s just nodding and agreeing,” she said. “But in my heart, I know that there’s something wrong with him and this isn’t exactly the right thing to do.”

Having found him a place to stay, but knowing Kenny was facing issues the homeless shelter couldn’t solve, my mom began picking Kenny up every day, taking him to get food and search for mental health resources. With so few appointments to be had, most days were spent driving around town listening to Kenny repeat his favorite stories and encouraging him to use the shelter’s showers.

Kenny lived in the shelter from July 2019 until December 2019 as the medical mystery surrounding his behavioral variant FTD was slowly unraveling. Throughout that time, my mom said she received no calls from the homeless shelter. When she called them for information, she was told they could not talk to her about Kenny’s files because it would violate privacy laws.

Scott Benton, a manager at Volunteers of America’s Reno Shelters Program, told me he sees the role of their services as putting the person experiencing homelessness “in the driver’s seat, and then I’ll ride in the passenger seat with them.”

“We empower them to be their own advocate with us right next to them, so that they aren’t doing it alone, so they feel like they’ve done something, they’ve accomplished it on their own,” Benton said. “We will guide them through the process of how you do it, this is where you go to do it and we’ll be there with them.”

Benton said the shelter tries to aid people in their programs as much as possible with finding housing, health care and employment. Understandably, the shelter can only do so much without the effort and cooperation of the person experiencing homelessness. Because FTD causes apathy and limited ability to understand and carry out instructions, Kenny could not accomplish the tasks he was given at the shelter.

At the same time Kenny had his first appointment with a neurologist to discuss his MRI results, he was kicked out of the homeless shelter. He had lice and refused to shower with the treatment. For sanitary reasons for the other shelter residents, he had to leave.

It then my mom learned Kenny was enrolled in a shelter program and assigned a social worker to help him find employment and housing. We did not find out he was in the program until he was being expelled from it.

But, almost serendipitously, the MRI results provided a major clue about the condition of Kenny’s brain. Spurred by social workers who said the MRI results could help place Kenny in a group home immediately, the next mission became getting rid of the lice so Kenny could move into a stable living situation.

They brought him to a hotel, where they dressed in personal protective equipment and administered the lice treatment themselves. The promise of staying at the hotel was the only thing that compelled Kenny to rinse the treatment.

“I literally had to stand there and watch my brother shower and rub lice treatment all over his body, completely naked, which was way more than I ever expected I’d have to do in my life,” my mom said.

Free of lice, my mom and aunts decided to pay for Kenny to stay in the hotel while they awaited his seemingly imminent placement in a group home.

At that point, we turned to GoFundMe. Between periodic hotel stays, daily meals, hundreds of miles of driving and new clothes and shoes (which he often refused to change into), my extended family paid thousands of dollars out of pocket for Kenny’s care in those first six months.

Before Kenny was diagnosed with FTD, my mom and one of her sisters decided the prohibitive cost was too much to face indefinitely while awaiting a final diagnosis. Kenny’s nurse practitioner verified he had cognitive impairment based on his MRI results and cognitive tests. This allowed us to apply Kenny for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI).

In the three months between when Kenny was kicked out of the homeless shelter in December 2019 and when he was approved for SSDI in March 2020, we raised nearly $2,200 through GoFundMe. That money was a savior. It paid for a few nights in a hotel and the first month’s rent of a tiny studio apartment in Downtown Reno. In perhaps another coincidence or sign from God, $2,200 is the amount Kenny began receiving in SSDI benefits each month. Those benefits now pay for his apartment and groceries.

The search for a group home or live-in care facility had a familiar refrain to the search for mental health care. Facilities cost a minimum of $3,500 per month, with little or no contribution from Medicaid. Even with his SSDI checks, we would need to pay at least $1000 per month to make up the cost, not feasible while putting two kids through college on a public-school educator’s income.

And that’s if he ever gets off the waiting lists (after nearly 18 months, Kenny is still on multiple long-term care facility waiting lists). Few facilities are willing to accept a 43-year-old man with Kenny’s particular needs. He can eat and use the bathroom himself and he is mobile. But his personal hygiene, executive decision making and response to emergency situations necessitate professional supervision.

Ozga confirmed there are limited resources of care for people with FTD, particularly people Kenny’s age.

“When it comes to having young onset brain disease, this is not the best country to be in,” Ozga said. He said sources like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security “are all really inadequate. Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot of options, unless you’re extremely wealthy can afford full-time long-term care and a private facility.”

In some ways, my mom sees Kenny living in the apartment as a blessing in disguise. If he was placed in a care facility or group home when he was expelled from the homeless shelter in December 2019, he likely would have been on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic, which ravaged long-term care communities.

Where Things Stand

Kenny seems content with the life he’s leading, and the stability has been accompanied by his symptoms moderating slightly. His stories are no longer as graphically violent. Instead, he likes to repeat the same memories over and over. The stories range from anecdotes about his kids’ favorite bands and superheroes to dancing with his future wife at the prom. He repeats the stories with such frequency, I can often mouth the words in perfect unison with him as he talks.

Beyond his typical speeches, he isn’t much of a conversationalist, though he laughs a lot. When I interviewed him for this piece, he never answered with more than five words. When asked what it was like returning to Reno from Missouri, or living in the homeless shelter, or moving to his current apartment, each time he replied, “It was interesting.”

I reached out to his wife Angela but received no response. They are still legally married, but she has not responded to any of the relatives directly caring for Kenny in almost a year, despite periodic attempts at contact.

Though Kenny still refuses to shower, one of my aunts has managed make haircuts and nail-clipping part of his routine. Every day he sees at least one of his siblings, who take him for drives to get lunch and bring him home-cooked dinners. He still prefers fast food and has a pervasive sweet tooth (peanut M&Ms make up a significant part of his diet, but we try to pick our battles). His Medicaid pays for a personal care assistant to come once a week to help clean the apartment and shop for groceries.

Political debates persist about the social safety net and helping those navigating the maze of homelessness, health care and welfare benefits. But it’s often forgotten that people who may be most in need might be unable to get help themselves. I can only imagine the struggles of people facing similar circumstances as Kenny without having the familial support he has.

Our family constructed a safety net of our own. It was woven over the years with incalculable frustration and grief; thousands of pages of paperwork and hundreds of phone calls; exorbitant time and money from an army of devoted siblings. Despite that high cost, Kenny’s not where he needs to be. FTD is a progressive disease, and his ability to care for himself will further diminish over time.

But we aren’t in despair. Also woven into that safety net are hope, love and resilience.