When you Google “how do you get sober,” Alcoholics Anonymous’ twelve step program will be a top result. If your doctor tells you to get sober, they’ll recommend the twelve steps. The court doesn’t send you to jail but instead says get treatment, you’re likely to end up in a twelve step based program.

For many, AA is their only understanding of alcoholism, which is defined as the inability to control drinking due to both a physical and emotional dependence on alcohol, also known as alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Beginning in the mid 1930’s by two cis-gender white men, AA now boasts more than two million members, a significant number given the some 15 million people the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism says suffer from AUD in the United States. Of which, less than seven percent receive treatment.

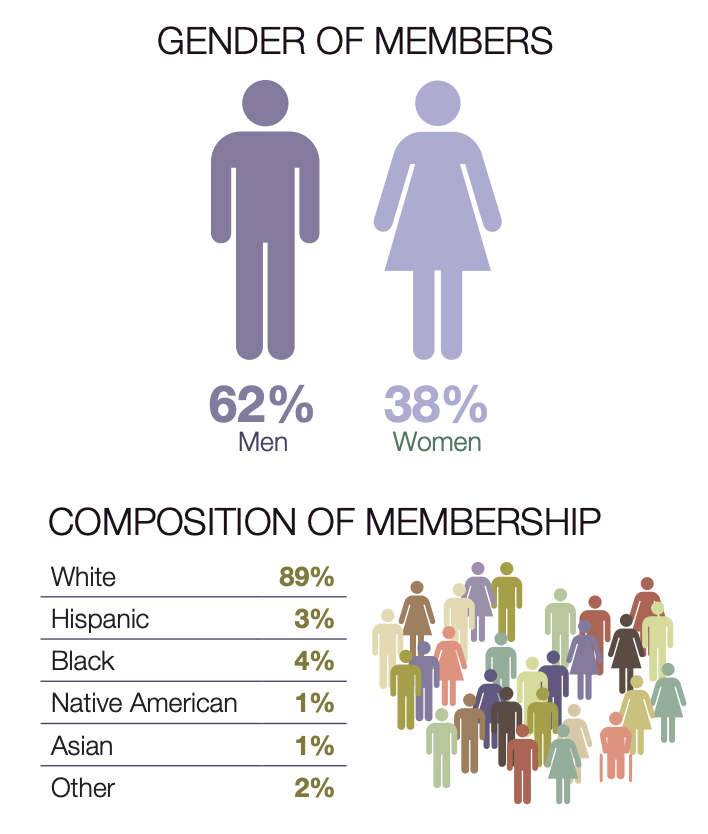

Although the Big Book, the sort of bible for AA, states that “the only requirement for AA membership is a desire to stop drinking,” member demographics, unreflective of the United States population, show nearly 90 percent of members are white and more three in five members are men.

AA meetings, however, remain a free resource, which is a critical component given that economically marginalized groups—such as BIPOC, LGBTQ and disabled folks—experience AUD at higher rates often due to the additional stress imposed by discrimination, known as minority stress and first researched in LGB populations in 2003.

Because most sober seeking people will be greeted by AA at some point, Lazarus Letcher—who is Black, transgender, non-binary (using they/them pronouns) and sober—believes reform rather than replacement of the program is needed.

“I see a lot of value in trying to change AA, and I’m not a big believer in like we can change it from the inside, but with AA I think it is possible because each group is autonomous, so I have seen groups do some pretty radical things,” Letcher said.

Most would consider Letcher an activist, with a six page resume filled with personal research, academic papers and speaking appearances solidifying it as a fitting title. But to Letcher the purpose behind advocacy for the Black and transgender communities is much simpler, and far more profound.

“I just don’t want to die.”

Letcher said of the risk Letcher’s various identities pose.

One in three transgender folks had to teach their doctor about transgender individuals in order to receive appropriate care this past year, said a study by the Center for American Progressive, a progressive nonprofit. As a Black person living in America, Letcher also fears police brutality, which remains an active threat shown in one of many examples with the murder of George Floyd in May 2020.

While AA excuses any “outside issues” from discussion, these two identities shape Letcher’s sobriety as they are part of Letcher’s lived experience. Letcher prefers to attend identity-specific meetings, a newer option for AA members, when available.

Like millions of other Americans, Letcher’s family has a history of alcoholism. According to many studies, children of alcoholics are about four times more likely to have trouble with alcohol than people without such a family history. In an effort to break the trend, Letcher’s father never took a sip of alcohol. He would often say to Letcher: “I’m more dangerous to white supremacy sober.”

Letcher learned what Letcher’s father meant by this through processing sobriety.

“I drank to numb and run,” Letcher said of past habits, “and could not often name what I was numbing and running from.” In a blind rage about white supremacy, Letcher reached a point of realization: drinking at white supremacy was only hurting Letcher

Getting sober allowed Letcher to take conscious action and focus efforts in a mutually beneficial way that set boundaries around their energy and created space for intentional advocacy.

“I’m more dangerous to white supremacy sober.”

Before sobriety, Letcher remembers getting blackout drunk at a gay bar following the Charleston church shooting in 2015, in which nine Black people were killed during a Bible study, and writing about it online, saying something like: “I took radical action today… getting sh*t faced and showing them that I can still have fun.”

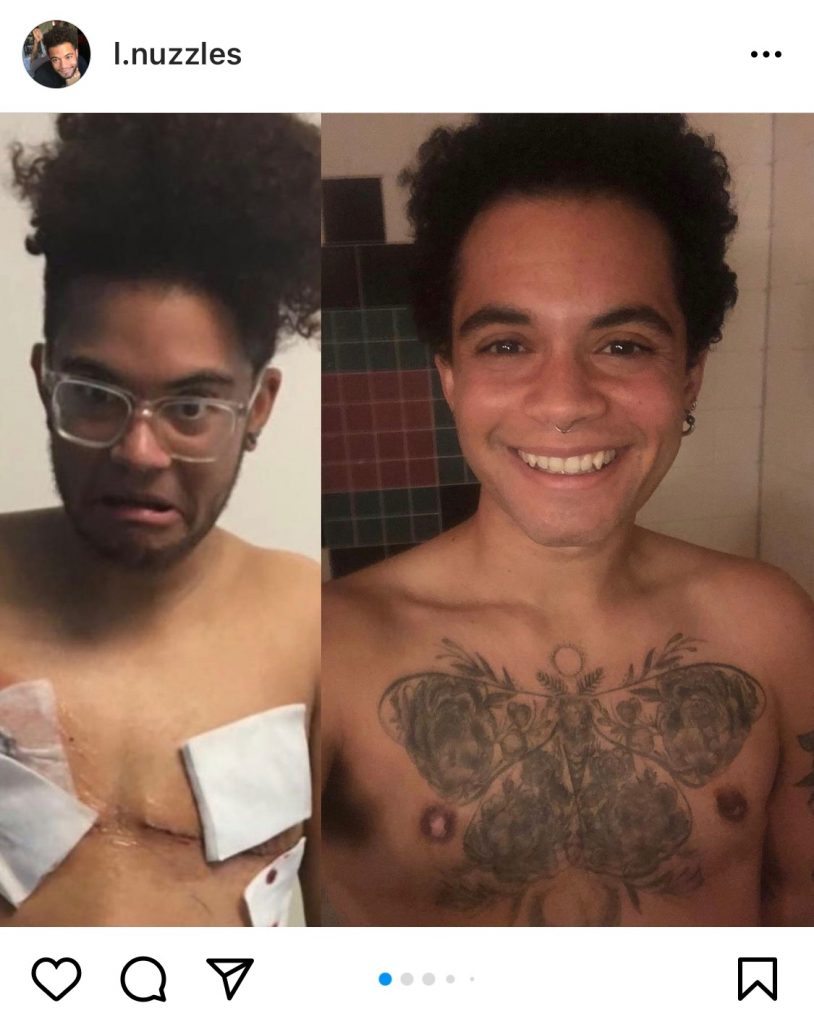

The only time Letcher took physical action against oppressive people was when drunk. Two days after getting top surgery—the surgical procedure that removes breast tissue common among transgender men—with drains still hanging from the surgery, Letcher attended a protest against Breitbart, a far-right opinion and commentary website. While alcohol coursed through their blood stream, Letcher yelled at cops in contest to the misogynistic, racist, xenophobic, transphobic right-wing media personality Milo Yiannopoulos who was popular on the site.

“That was a wake up call, just like recognizing that my behavior was not in line with who I wanted to be, and like how I wanted to show up for my community.” Then, Letcher’s direct action wasn’t community driven, but rather out of self harm, “like wanting to press a bruise,” Letcher said.

“I’ve gotten better at delineating where and how my voice or body are needed,” Letcher said.

Sobriety also grants Letcher the ability to think critically when protests get dangerous for protestors. “The big one was this summer,” Letcher said, referencing the protest in Albuquerque, N.M. in June that sought to topple a statue of Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate where one of their peers got shot.

“[I was able to] get on my bike and clear a nearby park and come back and report out to folks what was happening—to help more protesters not to come, and then to please come once the cops came.”

Changes happened fast when Letcher got sober. At one week, still experiencing the shakes—a sign of alcohol withdrawal where the part of the brain controlling muscles reacts to the alcohol leaving the body—Letcher applied for a PhD in American Studies.

“It feels like one of the arenas that I can have some impact… like my classrooms are majority young kids of color.” As part of the program, Letcher teaches a class at the University of New Mexico called “Peace Studies,” which they described as basically debunking that “everything you learned K-12 about America was a lie.”

Watching the sparks go off in students brings Letcher joy, “like having people come back and be like, Yeah, I talked to my grandma about that, she marched with Cesar Chavez.” They use academia as a way to empower others.

Yet, academics are often overworked and underpaid—a similar reality of being Black and transgender in the sober space.

This past summer, with the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the subsequent resurgence of Black Lives Matter, Letcher’s Instagram page got shared by prominent names in the sober space as part of a popularized “passing of the mic” trend online and the broader sharing of social media with others beyond, in this case, the Black Lives Matter movement. Activists like Letcher were rarely asked if they were okay with their page being shared to millions of people seeking educational resources.

“I just remember waking up and I’m like why are there 100 white women in yoga pants suddenly following me, like what happened and being like, Oh Laura Mckowen shared my page,” the author of We Are the Luckiest: The Surprising Magic of a Sober Life, who has 77.2k followers on Instagram. “I was not asked about that.”

On first glance one might see this act as gracious, helping another build their community. But what many cisgender white folks may not understand is the emotional, unpaid labor this person then has to do to educate others about their lived experience as a member of a marginalized group. Letcher received direct messages asking endless questions or hurtful comments. Some sober places shared Letcher’s Instagram and also venmoed $50, which Letcher felt fine accepting.

Sober Voices Summit

At the same time the “passing of the mic” phenomena gained traction on Instagram, 30-year-old Phoebe Claire Coneybeare had her own “aha” moment while relaxing in the bathtub one night in August.

Three years sober and queer herself, having just quit corporate America, Coneybeare remembered something a mentor said to her: “you don’t have to be the one always on the stage. You can be the one creating stages for other people.” And create stages she did.

Picking up the phone, Coneybeare called longtime friend, former roommate and her initial sober inspiration, Alyssa May Hart. The two friends met through their sorority Delta Zeta while in school at Eastern Michigan University. Both shared an interest in social justice throughout their lives, always trying to be critical of themselves and systems. Coneybeare studied international affairs and economics. Hart studied sociology, criminology and political theory.

The combination of their education, work history in the events spaces and own lived experiences gave way to a first of its kind event: the Sober Voices Summit.

Marketed as “storytelling for the full spectrum of sobriety,” the Sober Voices Summit launched as a three-day speaker conference with 700 paying attendees on February 4-6, 2021. With 40 speakers, including the founders, some topics encompassed: “Being the French-Colombian Girl of Your Dreams Kept Me Addicted, Facing Disability Stigma: To Disclose or Not?, Sober & Thriving with Bipolar: An Asian American Perspective.”

The intention of the summit was clear: structured inclusion should be mandatory for events.

Such a process was long overdue in the sober space. “One of my good friends who’s sober and a Black man participated in a virtual event where he was the only speaker of color and when they put out marketing assets, his photo was just the only one missing,” Hart said, one example of many.

Coneybeare and Hart, as two white women, sought out to center non-white voices in this conversation, a reality front of mind. Even with their educational backgrounds and various other identities, they knew they couldn’t do justice to all the communities they hoped to serve without proper guidance and necessary accommodations. In comes M Valentine, DEI consultant, and people and culture expert.

“When we first talked. [M] had a qualifying conversation with us and said like why are you asking me to be a part of this, why is inclusion work important to you. And we told her a lot of what we’ve told you like that, that we just think it shouldn’t be… none of this stuff should be an afterthought anymore,” Hart said.

“Our inclusion advisor and the folks who surrounded us were like, keep trying, keep showing up and be uncomfortable,” Coneybeare reflected, “We were uncomfortable, a lot. That’s okay, we were challenged.”

“We were uncomfortable, a lot. That’s okay, we were challenged.”

Not only did they pay their speakers to combat the industry norm of free storytelling, “it was important to us to say, people who do emotional labor and who share their lived experience through story deserve to be compensated for their time and energy and vulnerability. That was radical, and our inclusion advisor supported us in that,” Coneybeare said. But the Summit also included sliding scale ticket prices, a practice of pricing that “attempts to take historical oppression, systemic racism, and the multifaceted aspects of someone’s current identities and levels of financial access into consideration when crafting pricing tiers for a service, product, or event,” according to their site.

Letcher was one of the 40 speakers at the Summit and gave a talk titled: “Who’s Missing? Making Sober Spaces More Inclusive and Accessible.” Letcher commended the founders for paying their speakers and including the tiered ticket pricing. Yet, according to Letcher, the fact that white women put on a sobriety event wasn’t nuanced at all.

“I’ve done a lot of sobriety events at this point, and I have never been a part of one that wasn’t organized by white woman, so it’s just kind of par for the course,” Letcher said.

Yet in the combination of efforts, Letcher found something new. “The fact that it was paid, that it was majority BIPOC speakers, and like I also wasn’t the only trans voice. So it was the first time that I had all three of those for a sobriety event.”

The event happened. Many were pleased. But still, it wasn’t perfect. Hart says that wasn’t their goal throughout the process: “The priority was not in productive output.”

“It was hard, and it was important to do. And it wasn’t perfect like we have accountability work we’re doing right now because there was harm that occurred at this event,” Coneybeare said, referencing the live keynote conversation on day three, February 6, between Holly Whitaker, founder of Tempest sobriety school and author of Quit Like A Women, and Carolyn Collado, founder of Recovery for the Revolution.

Letcher, who now works for Tempest full-time as the main BIPOC community facilitator, was working at Tempest part-time during the Summit. Letcher admits that while they “adored being able to have that platform, and geek out about the history of recovery… like how rooted in whiteness it is, and how white twelve step programs still are,” that it was also tricky working at Tempest during the fallout.

“We just spent like, two or three weeks where like every call we had was just about like what… did Holly do? What had happened? And feeling very betrayed and was very [frustrated].”

Letcher did not defend Tempest. “They should have released a f****ing statement.” Sober Voices reached out to Letcher, although Letcher admits they didn’t have the capacity at the time to address the situation due to all that needed managing internally at Tempest.

“[Sober Voices] did handle it pretty well, but also just so many of the attendees were also white and just like didn’t see any issues with that conversation,” Letcher said.

“Folks that I know are really hurt that the chat was made unavailable as well, which felt like kind of dodging of accountability… I think they did everything the best they could have, right, and then the way the keynote went really sucks for them.”

Tempest founder Holly Whitaker has since moved away from her duties as Chief Operating Officer and into a new role, Chief Creative Officer. Stepping in is health tech industry leader Ruth Sun, with more than 25 years of experience in technology and leadership—18 of which spent with IBM (Watson Health).

“Tempest has been ahead of its time since its creation in 2015 and has modernized alcohol recovery with evidence-based outcomes…. Tempest has known for years: anyone, at any time can decide to change their relationship with alcohol, no matter where they fall on the spectrum of excessive alcohol consumption,” Sun said in a PRN newswire on February 16. “I am thrilled to help Tempest capture this groundswell of awareness as the category leader in the modern recovery industry.”

Modern Recovery + Sobriety’s Toolkit

“Sobriety, it’s a lot more than stopping drinking. Because if you allow it to, it will change your identity,” Ella St John McGrand, mindset coach and history documentary TV producer based in London, England, said of the trickle down benefits she found from quitting drinking.

“Sobriety it’s a lot more than stopping drinking. Because if you allow it to, it will change your identity.”

In November, McGrand published a personal essay on the Tempest website titled: “How Sobriety Reconnected Me to the Legacy of Slavery.” Nearly two years ago, around the time she got sober, McGrand got brought on as an assistant producer for the television series 1,000 Years of Slavery—a show aimed at revealing the connections that link the history of slavery to modern communities across the world.

“I was a few months into my sobriety. And it was a really difficult television series to work on,” McGrand said. Television production is typically stressful, but it was the content and the timing that made this project different. “I’d done a few shows about the issue of slavery before, but I never really engaged with it on a deep level.”

From stopping drinking, McGrand was forced to feel all the emotions the topic brought up within her own identity. “It was a lot more raw… and I was really questioning my identity and how I felt about being a mixed race woman and being a person of color.”

Working on that series of slavery while simultaneously working through sobriety on her own terms, McGrand was forced to consider how her ancestors would have felt. She knew that they were transported from West Africa but didn’t engage with the thought much further, unconsciously choosing to focus on the “good” parts of her identity, having Caribbean heritage.

“I didn’t necessarily want to talk about or think about, the more gruesome or violence, the violence of it, I think I’ve kind of pushed that down.”

By calling her white ancestry good, in quotes, McGrand is pointing out the historical portrayal of whiteness.

“The proximity you have to whiteness, the more desirable you are. And I thought, as a mixed race woman, I occupy a really interesting space where I’m obviously black and white at the same time, but because I have this proximity to whiteness, that’s now seen in today’s culture, as something ‘good,’ exotic,” McGrand said.

She points out the 217k posts on Instagram today with the hashtag mixed race babies as “poisonous” because it’s forgetting the roots of it. And that actually, it’s celebrated because of its proximity to whiteness.

“Back then it meant something different, because you would have been born out of a relationship, probably a rape between an enslaved woman, and you know, an overseer or the master of the plantation.”

The moment where these feelings came to a head for her was when she was researching a document called the Barbados code, named after Barbados, a British colony, and which enshrined into law how the Negro race was subhuman.

McGrand didn’t find sobriety through the typical Alcoholics Anonymous route. While training to become a mindset coach, she noticed that for many of the sessions, which were on Sunday mornings, she was hungover, and not giving it her best. McGrand thought, “Oh, this is interesting that alcohol is really impacting this training, this coaching training that I really want to do, that I’m really passionate about.” A couple of weeks after her 30th birthday, in a point of inflection, she just decided that was it.

“Because I’ve been reading about these tools and self awareness and being honest about where I wasn’t, and the process of being coached myself and coaching other people, I could now take a step back and see alcohol is interfering in my life in a negative way.” She asked herself: “How am I going to move forward? What is the plan?”

The answer was clear: you need to stop drinking.

Since she stopped, she found her lost confidence in her opinions. Without the danger of slurring words or unnecessarily repeating herself, McGrand finds more assurance to stand up for herself and her beliefs, not only with friends but in her work. Previously, McGrand would have shied away from conversations about race and representation or rather had them at the bar, a few drinks in.

The tools McGrand learned in sobriety are the same needed to advocate for herself.

Those tools?

“It’s self awareness. It’s empathy. it’s listening. it’s willing to look, willing to take responsibility for what you’ve done. And then looking at how are you going to change it,” she said.

“It’s the action that you take.” In sobriety, the action is not drinking. In activism, the action is voicing your needs and calling out harmful behavior.

Letcher, Coneybeare and Hart also agree with McGrand’s toolkit idea. Similar to the set of tools that got McGrand sober, AA shares their own common phrases and ideas.

“One day at a time” is a common phrase in the sober space as the thought of a lifetime without alcohol can at times be too overwhelming to consider. Overwhelm is a well-known feeling among those tackling a social issue.

Like so many alcoholics, Letcher always had ADHD, having to constantly regulate impulses. They credit learning to address what they’re feeling as allowing them to better trust their impulses.

“Just gaining one more second before I react to something has helped me trust myself a lot. Like, should I speak up here? No, no,” they tell themself, “I’ll speak up.” And when it comes to taking care of themself after a protest or another police brutality against a Black person, Letcher says it’s the tools they learned in sobriety that they turn to rest.

Burnout rates among activists remain high.

Benefits from the skills learned in sobriety stretch beyond avoiding a bottle.

Coneybeare says she would have never left corporate America if it weren’t for her sobriety. “I built my own self esteem and my resilience and trust in myself enough where I could take this risk… I always wanted to be an entrepreneur, and I remember when I was still drinking, I would be writing out all my grand plans on Google Docs and never following through.”

When she quit, giving herself the space and time to focus on her needs, she gained confidence in her voice. At three years sober, she’s finally ready to act on those desires. “I feel like I have something to say. I want to make a mark. I want to have a legacy. I want to do something different.”