The Future of Concerts is Digital: How COVID-19 has Changed Live Music and Entertainment

There is almost nothing that parallels the experience of going to a concert when your favorite artist is performing.

It’s hard to pinpoint what makes live performances so immersive—the energy of the crowd, the music pulsing through the air around you or seeing these larger-than-life characters in front of your very eyes—but regardless, it’s an experience that’s almost impossible to imitate.

During this year-long Post Concert Depression, music lovers have wondered when they’ll be able to experience the zing of the brass or the reverberations of high strings, the heat of a crowd or the cool AC in an auditorium. For many who enjoy experiencing live music, the 2-D online concerts that have replaced them seem like shallow imitations at best.

But with a vaccine on the horizon it begs the question: what will concerts look like post-deadly pandemic?

Jae Deal, a music producer and adjunct professor at USC, had a lot to say on the matter. Deal, who has over 30 years of experience in the music industry playing in live bands, composing and producing music for artists like Lady Gaga, Snoop Dogg, and Elton John, predicts that the future is digital, and online and virtual concerts are only going to get more advanced and immersive.

“We [artists] have learned so much about how to engage people and put on a show without being there in-person,” Deal said. “Whereas before we would have been talking about virtual reality, I think now we’re going to have something like augmented reality [or] augmented virtual reality.” According to Deal, an ideal experience would be a hybrid of both augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to “enhance the virtual experience.”

Aside from sight and sound, all of the senses—touch, sound and smell and even taste—would be engaged in order to create a more realistic experience for the viewer.

Although both AR and VR technology isn’t quite that developed yet, Deal is convinced that this tech is the future of concerts and live performances. He said that this experience can’t parallel the feeling of being in a crowd, but it’s definitely a viable option for fans who want to can’t be there because of budget or time constraints.

And it seems all the more likely, given the fact that Deal suspects ticket prices are going to jump dramatically from what they were before.

“Just a little inside [tip],” Deal started. “When [concerts] start up again, ticket prices are going to be sky-high. And [companies] don’t care, because they’re compensating for the deficit in numbers by hiking up the prices of tickets and the add-ons.”

It makes sense why Deal thinks ticket prices are going to skyrocket. The live entertainment industry is projected to lose close to 10 billion dollars in revenue after cancelling and postponing concerts in 2020. It’s an expected step for companies looking to make back their lost revenue, but for everyone who isn’t ultra-rich, what are companies doing to make live music accessible?

Augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR) concerts are looking more and more like the solution to this dilemma. Not only will they help companies and artists increase their revenue, they could also act as a more affordable option for fans to see and experience their favorite artists “live”.

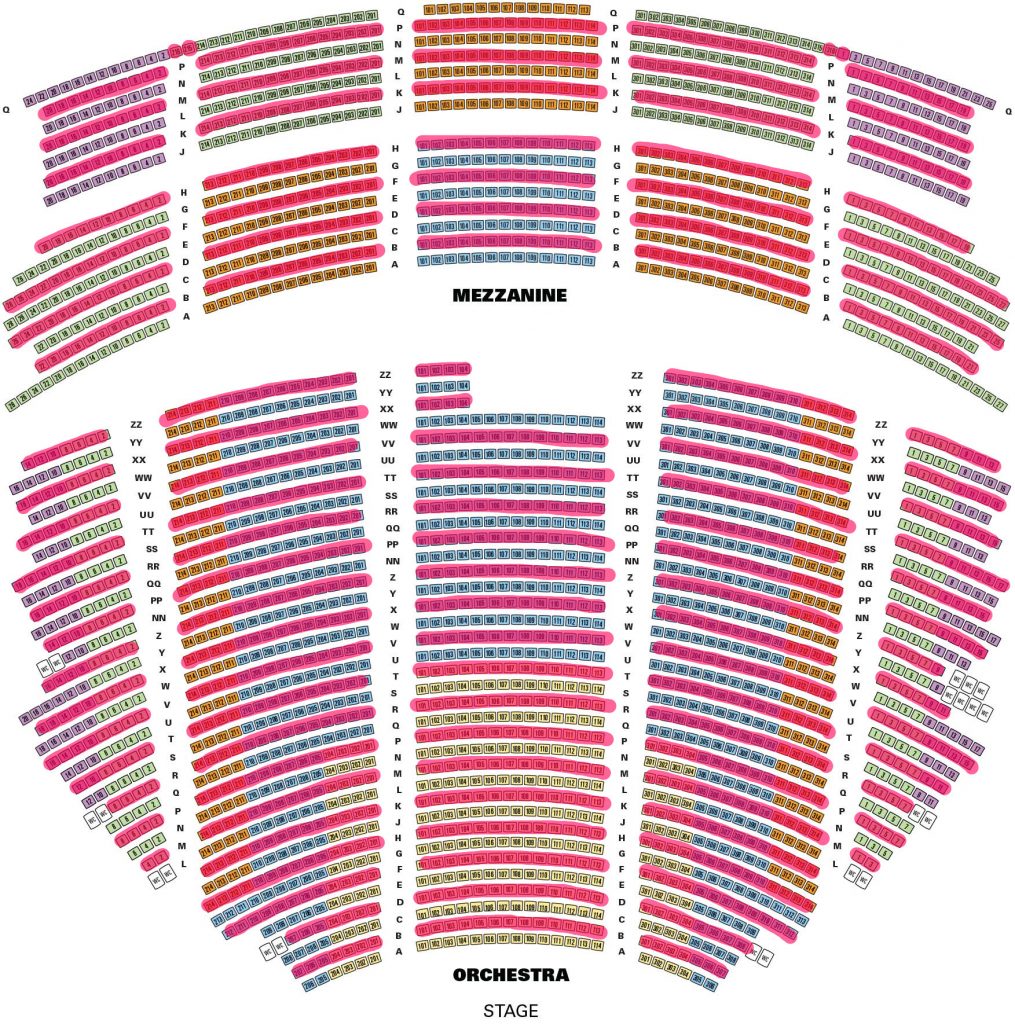

The idea is simple: instead of paying hundreds or thousands of dollars on a ticket, fans would be able to purchase much cheaper tickets for a virtual reality “seat” at a venue. With the help of a VR headset and some (preferably decent quality) headphones, people could experience the feeling of being at a concert without actually…well, being there.

Deal thinks an idea like this could be game-changer in live entertainment. “Jay Z might be doing a concert in Minneapolis, but really it’s a global event,” he said. “Maybe one or two seconds before the world sees it, Minneapolis is seeing it. It could be an amazing thing and really bring people together.”

When asked if he thought audiences would gravitate to this new way of experiencing entertainment or prefer a traditional concert venue, Deal pointed out that music lovers had already been experimenting with augmented reality concerts long before the pandemic.

As early as 2016, virtual reality concerts were being test-run and receiving feedback from consumers. Companies like concertVR, NextVR and MelodyVR have been at the forefront of the movement to take concerts and other live performances and events virtual. One of the biggest advantages to the new tech—provided that you have a strong internet connection—is the clear, close-up view of the stages and performers. Imagine: you can spend an hour and a half (or more) standing less than 50 feet from your favorite artist or performer. You wouldn’t have to worry about getting your feet stepped on by a stranger, or having to strategically maneuver yourself to see behind someone’s head. Depending on the concert, the artist or group could even have interactive events, like in the Jonas Brothers’ most recent online event.

But other artists, such as Post Malone, have already entered head first into the VR space. The video below is an example of the kind of 360 VR experience music-lovers can expect to see more often in the future.

Some networks—like SBS (Seoul Broadcasting System)—have gotten their hands on more refined VR technology, and have tried recording special performances with musical artists like ITZY.

It’s an interesting concept that could potentially make companies even more money, since they no longer have to worry about constraints like venue capacity. A concert held in a stadium with a 10,000-person capacity can now host hundreds of thousands or even millions virtually.

But still, it’s not a concept that sounds so appealing from the perspective of a fan. Heran Mamo, a staff writer at Billboard and a music-enthusiast, admits that while virtual reality concerts would be a step-up from online concerts now, AR and VR won’t be her first choice for attending live performances.

“I think that if [live performances] are going to continue in this virtual route, honing in on the personalized experience might be a better approach,” Mamo said. “I feel like, if you’re trying to make it seem like ‘we’re all in this together, this is a global event’, it just doesn’t feel that way when you’re at home, by yourself, watching your favorite band play from your laptop.”

According to Mamo, one of the few positives to online concerts now are the added video effects, but even that didn’t make up for the loss of in-person entertainment.

“With music, it’s primarily an audio experience,” she explained. “The difference between hearing music streaming from your computer, from your phone [or] your headphones does not resonate the same as [speakers] booming in a venue.”

Even though she’s working her dream job, it’s lost some of the initial allure since she hasn’t been allowed to travel. Nowadays, red carpets and front-row seats have been replaced with watching live streams from her couch.

“When you work in the field of music news, you’re always being thrown this way and that,” Mamo said. “I purposely moved to Hollywood so I could be in the center of it all. It’s been over a year since I went to a live show and sometimes you don’t even think you’re working. You’re just on your laptop and you’re writing up news that [usually requires] movement. When you take that out of the equation I feel like I’m not really doing my job.”

According to Mamo, even if AR and VR prove to be a new facet of experiencing music and live artistry, nothing will compare to being at a venue in person.

“Something within your ears and within your heart shifts when you see your favorite artists on stage, and it’s almost like a holy event sometimes.”

But if anyone is eager to get back to live performances, it’s the artists themselves. Singer and songwriter Madison Deaver, 21, has been performing since she was 12, and says there’s no experience quite like being in front of a crowd.

“I’ve done a few virtual performances and they’re definitely not the same,” she admitted. “The reason I love music is [to] connect with people. You get an adrenaline rush being on stage and performing in front of audiences, and when you can’t get that you’re kind of like “Oh, I have to find mine [someplace else].”

Although virtual concerts are not her preferred method of performing, she also understands how they might be necessary post-Covid.

“I don’t know if I’d be super into augmented,” Deaver said. “I think that’s the best option now until it’s safe for us all to be together in one place. [But] as the artist, I want to be surrounded by everyone, I want to hear everyone singing the songs with me. I would want to be connected with everyone there.”

So the consensus seems to be that while augmented and virtual reality concerts won’t be able to mimic the experience of attending a live concert, it’s still—in theory—a good addition to the live music experience to explore post-pandemic.

But like with any good thing there’s always a catch. Jae Deal worries that companies will want to take advantage of this emerging field of music at the expense of audiences.

According to Deal, the main issue with this new kind of technology is that corporate entities could decide to hike up prices of tickets and technology so high that they “exclude the disenfranchised or underserved people.”

Already, one of the issues with trying to make this kind of technology wide spread is that Ar and VR headsets are not always cheap. Depending on where you shop, high-quality headsets can cost up to $1,000. Given the fact that in 2019 the average cost of a ticket was $95, asking for music lovers to make that initial payment in addition to a ticket seems like a big commitment.

And what about the other aspects that come with live entertainment? Artist meet-ups, buying merch, being with friends and experiencing an incredible performance in the same space: is all of that really comparable to sitting in your room with headphones and a headset? Will it be enough to help with this perpetual feeling of Post Concert Depression?

And it’s not only the musical aspect of performances that audiences are missing out on. There are many facets to live entertainment, and an equally important part for artists and audiences are live interviews and interactions.

Mamo said that there are so many little characteristics about a person that reveal more about who they are and make them come across as more human, and mentioned that she enjoyed watching an interview between Billie Eillish and an interviewer Zane Lowe, where he commented on her casually cracking her knuckles.

“There’s things that are so human, they’re so mundane,” Mamo said. “But it was also just beautiful to witness at the same time. It’s how you would observe someone in real life that’s in front of you, and that’s an experience we’ve all not been allowed to have in a long time.”

“I feel like over Zoom there’s glitches, or someone freezes or they could be [telling] this amazing story and really technical problems get in the way of that.”

Thando Dlomo, multimedia journalist, keynote speaker and producer at Entertainment Tonight has witnessed just how much interviews and the content in interviews has changed now that the artists cannot be in a studio. But contrary to Mamo, she thinks that the change feels more intimate rather than distant.

“When I talk to a celebrity and she’s in her actual kitchen tells me so much about her,” Dlomo said. “Her kid might jump into the interview and how she interacts with that child tells me so much about her. As far as you are, I feel closer to you than I would in a studio with your gown on and your hair and your whole team trying to make sure you’re saying the perfect thing. It’s humanized us, for sure.”

Harvey Mason Jr., Interim CEO for the 2021 Grammy Awards, agrees. According to Mason, it’s possible to utilize technology to bring people closer together. Despite the limitations of in-person filming this year, Mason and his team produced an awards show on multiple locations with various lighting and stage arrangements. When asked whether or not he thinks the investing in VR to make the award show a more immersive experience, he said it was a definite possibility.

“I think that (VR) is the future of entertainment,” Mason said. I think we’ll see a lot more of that. I do believe there are some limitations around broadcast television, and I absolutely see [VR] as being a part of our future. I would love to learn more about it myself.”

But this kind of technology is not just limited to live concerts and performances. In fact, USC digital journalism professor Robert Hernandez has been utilizing VR for the past several years to make his stories more immersive.

Since first starting his work at USC in 2009, Hernandez and his students have focused on using emerging technology to connect audiences with stories they may not be able to relate to. In the spring of 2016, Hernandez’s class worked in collaboration with ProPublica to create a VR story about the disaster at the Houston Ship Channel. Hernandez has been using VR in his classes ever since.

“We’ve done stories on climate change, on homelessness, on deportees, on youth in foster care, on cultural burns, [and] COVID” Hernandez said. “We’re in post-production on a series about women who survived domestic abuse and intimate partner violence. Right now we’re finishing up a project with ABC news [about] a woman in the 30s named Katherine Cheung, who is the first Chinese woman to get a pilot’s license in the United States.”

Hernandez said that he and his students try to make their stories for and about disadvantaged and overlooked communities. Despite the fact that not all people have their hands on a VR headset now, Hernandez thinks there’s still ways to experience this kind of technology that won’t break the bank.

“Everything thinks that [for VR] your need a high-end headset,” Hernandez said. “You don’t. You have a phone, I have a phone, everybody has a smart phone. With little Google cardboard, you can bring it up to your face and [feel] as if you put on a headset. You do need electricity, and you do need the internet; that’s the requirement to produce and consume in these spaces.”

Hernandez thinks that it’s inevitable that this technology will become integrated into everyday life the more it advances. And it seems as though it already has. Over the past 3 years, VR technology has been increasingly studied by psychologists. Beyond video games or digital concerts, VR is being experimentally used in order to treat patients with PTSD or allow medical student to practice operations virtually. The ways this technology is being used suggests that the possibilities are endless. Perhaps you can attend a VR lecture when you’re at home sick, or perhaps you can strap on a headset and experience life on the surface of mars via a VR Mars Rover.

For concerts and live performances specifically, Hernandez wonders how the rights to VR performances will impact artists now and with even more advanced technology in the future.

“What are the challenges, what are the ethics, who makes the money, and who has the control? [If] the hologram of Tupac made an appearance at Coachella, would Tupac be okay with that? Who’s making the money off of that? Is it the Tupac Estate?

Prince dies ‘X’ amount of years ago this month, would he want a hologram to be there? What if he was alive and recorded a hologram, and now he can appear at whatever stage you want. Does he get paid, or does [whoever] captured him or the record label get paid.”

There’s clearly lots of different aspects to consider as VR technology is refined into something visually immersive. Where the money goes, the logistics of capturing VR imagery, and –most importantly–how VR compares to a live performance. On all accounts, VR and AR technologies seem to be an experience all on their own, and are on-track to being commonplace in many different fields outside of live music. It may seem like a foreign concept now, but music lovers should still consider this experience a viable option post-pandemic.

There’s nothing like seeing your favorite artist perform in person—but perhaps VR can be the next best thing.

Leave a Reply