Kellie Adolph stood determinedly outside of the Fresno County Office of Education, gathered with hundreds of other parents, ready for action. They were holding a protest against vaccine and mask mandates in local schools. This protest was merely one of hundreds held across the country that shouted the same sentiments.

Kellie Adolph and parents from the Clovis Unified School District protesting mandatory masks and vaccines outside of the Fresno County Office of Education Building and before a school board meeting, respectively

Guided by intuition, perpetuated by misinformation, and reinforced through communities of skeptical individuals, vaccine hesitancy has become omnipresent throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If COVID-19 vaccines were truly efficacious and safe, I would have no qualms,” said Adolph, a paramedical tattooer and mother of two from Fresno, California. Her job entails using tattoos to conceal scars, stretch marks, discolorations, or to ink realistic anatomic impressions. But after three years of ongoing research, clinical trials, and accelerated studies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have repeatedly demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine.

In fact, COVID-19 vaccines were evaluated in tens of thousands of participants in clinical trials, and the outcomes have all verified its safe and effective use.

Adolph wasn’t convinced.

It’s how she found an entire realm of epidemiologists, neurologists, and virologists whose reservations and skepticism align with her own. These pockets of the internet propagate dangerous misinformation spread and lead to misinformed decision-making.

With their help, she decided to take Ivermectin when she contracted COVID-19 last summer.

Ivermectin has not yet been FDA approved for treating or preventing COVID-19. High dosages of the drug can result in a wide range of adverse outcomes, including allergic reactions, balance issues, seizures, and sometimes death.

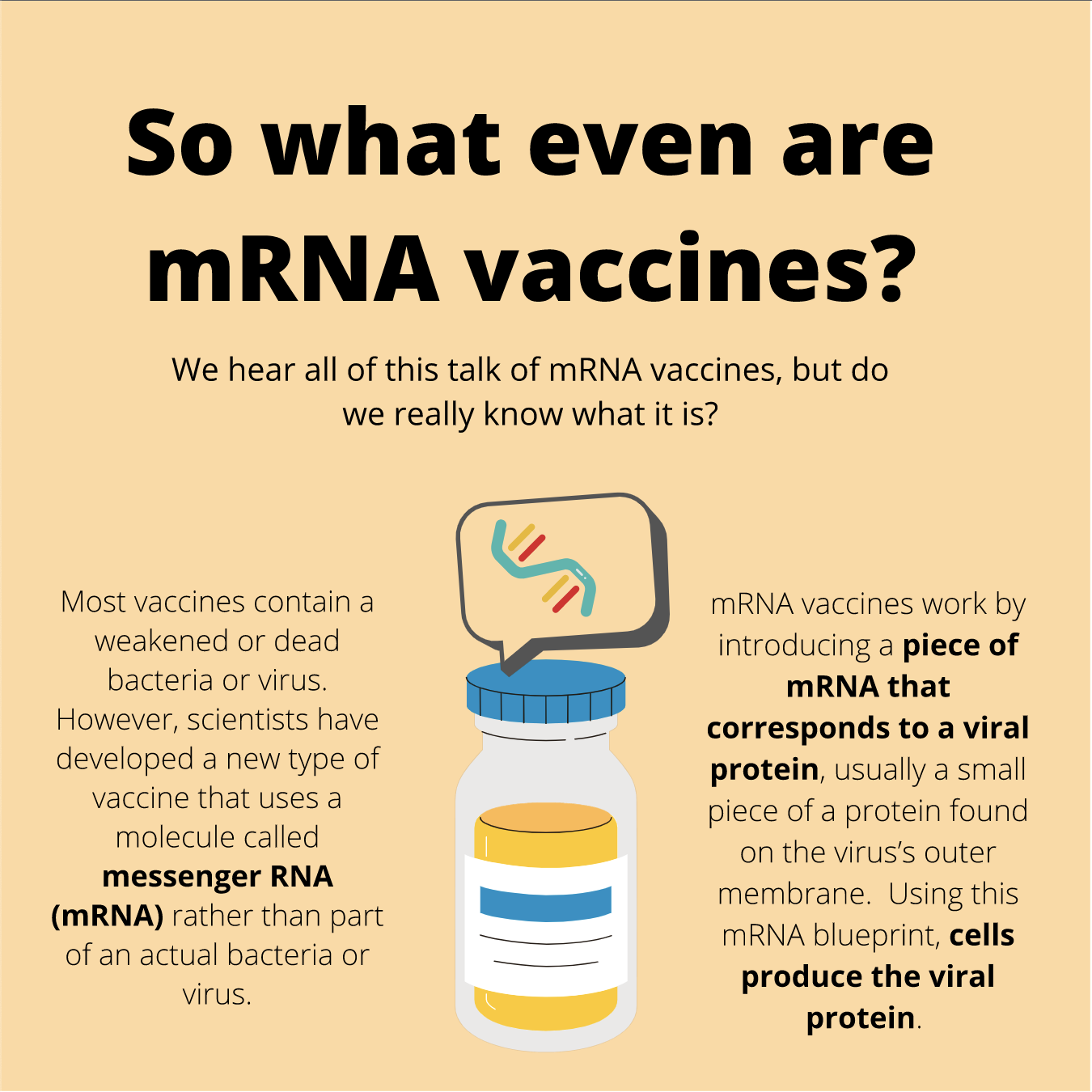

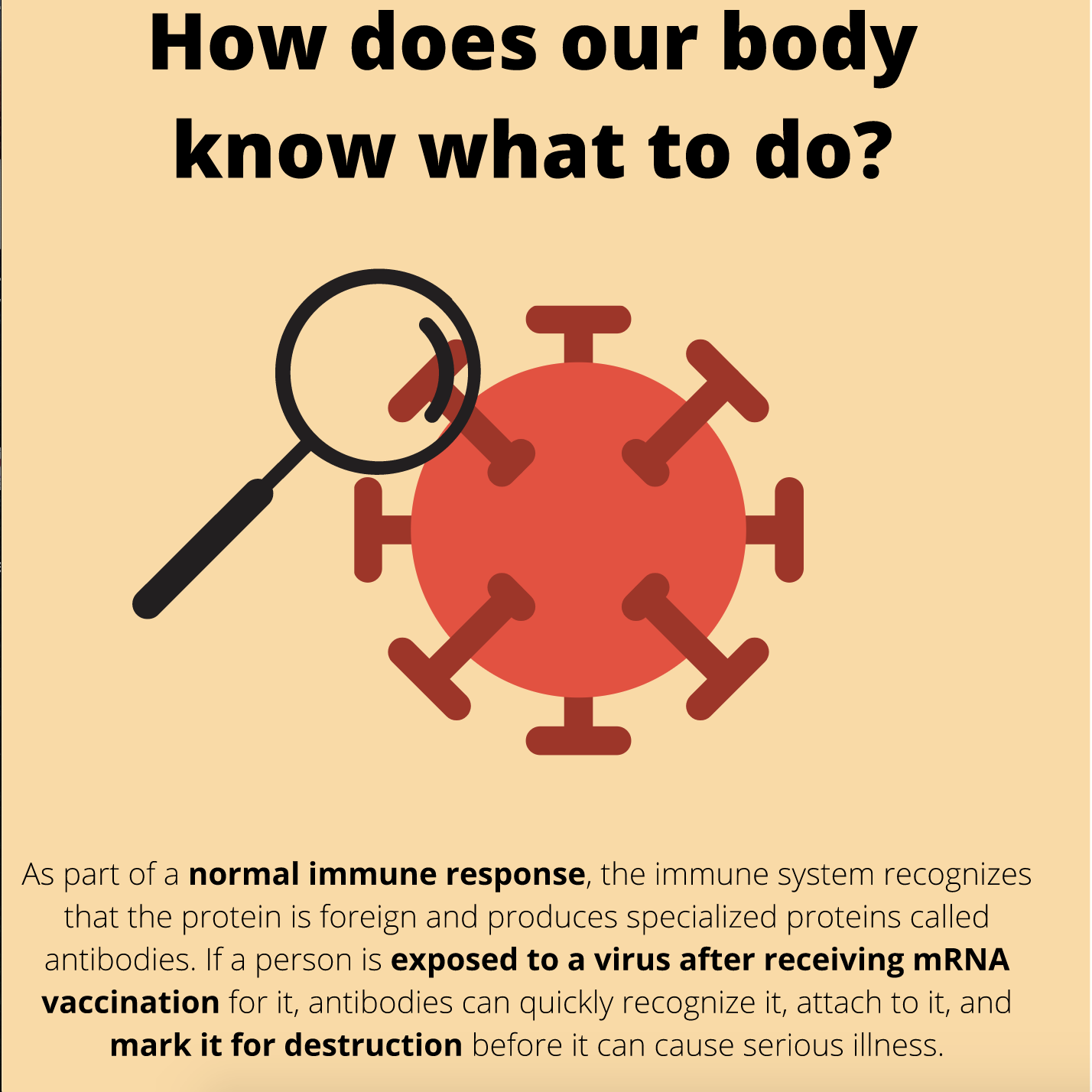

But masking up and getting vaccinated are some of the most protective measures that can help slow the spread of COVID-19. According to Mayo Clinic, masks are meant to protect the wearer from contact with droplets and sprays that may contain germs. A medical mask also filters out large particles in the air when the wearer breathes in. Additionally, mRNA technology used in the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines has been in development for over 15 years and has met rigorous safety standards.

Vaccine Hesitancy Over the Years

Despite consistent and ongoing evidence of vaccine safety, the resolve of individuals who believe the vaccine is harmful or powerless runs deep.

In fact, vaccine hesitancy was rated as one of the top ten threats to global health in 2019, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The contentious issue, however, is no novel concept. In its infancy in 1798 when the smallpox vaccine was developed, vaccines sparked controversy.

Now, as we continue to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, unwavering skepticism surrounding the vaccine persists, but those with less intransigent feelings have reduced in number over the past two years. According to a survey conducted by Kaiser Health, a large proportion of individuals with gentler hesitancy ultimately decided to get the vaccine.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Coupled with the prevalent views of surrounding communities, our willingness to take vaccines also consults our trust in science: another trend that has plummeted over recent decades. In the 1970s, 75% of Americans reported having trust in medical professionals. Today, only about a quarter report confidence in the healthcare system, according to The New England Journal of Medicine.

Adolph fits into that 25%.

“I’ve never been against vaccines before, but after all of my own research, I’ve discovered that vaccines aren’t as safe as I’ve always believed that they were,” continued Adolph. “Now I’m more hesitant since I’ve built this distrust in Big Pharma and the mainstream media.”

Julie Rovner, a health policy journalist for Kaiser Health News who covers vaccine hesitancy and other public health issues, commented on the role of institutional trust in guiding health decisions.

“The Lancet Study said that the countries that did the best in the pandemic were those that had the most trust in government,” said Rovner. The Lancet journals are both a destination for publication and a platform to advance the global impact of research.

In addition to her institutional distrust, Adolph was also cynical toward the relatively speedy development of the vaccine.

“I don’t trust how they have dealt with the virus, how quickly the vaccine was rushed to the market, and this ‘one-size-fits-all’ vaccine,” said Adolph.

Willman noted it is simply not feasible to wait years during a global crisis. In spite of the constrained time frame to mitigate the virus’s rapid spread, COVID-19 vaccines went through an accelerated approval process after completing required and standard phases of vaccine development and testing. The speed of developing the COVID-19 vaccine also comes from scientific precedence and a large, global scientific community.

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, manufacturing processes have been ready early on in the COVID-19 pandemic due to prior advanced research. Countries also shared genetic information when it was available, further contributing to the accumulation and dissemination of data. Vaccine developers also conducted some stages of the process simultaneously, rather than skipping any steps, to gather as much data as quickly as possible.

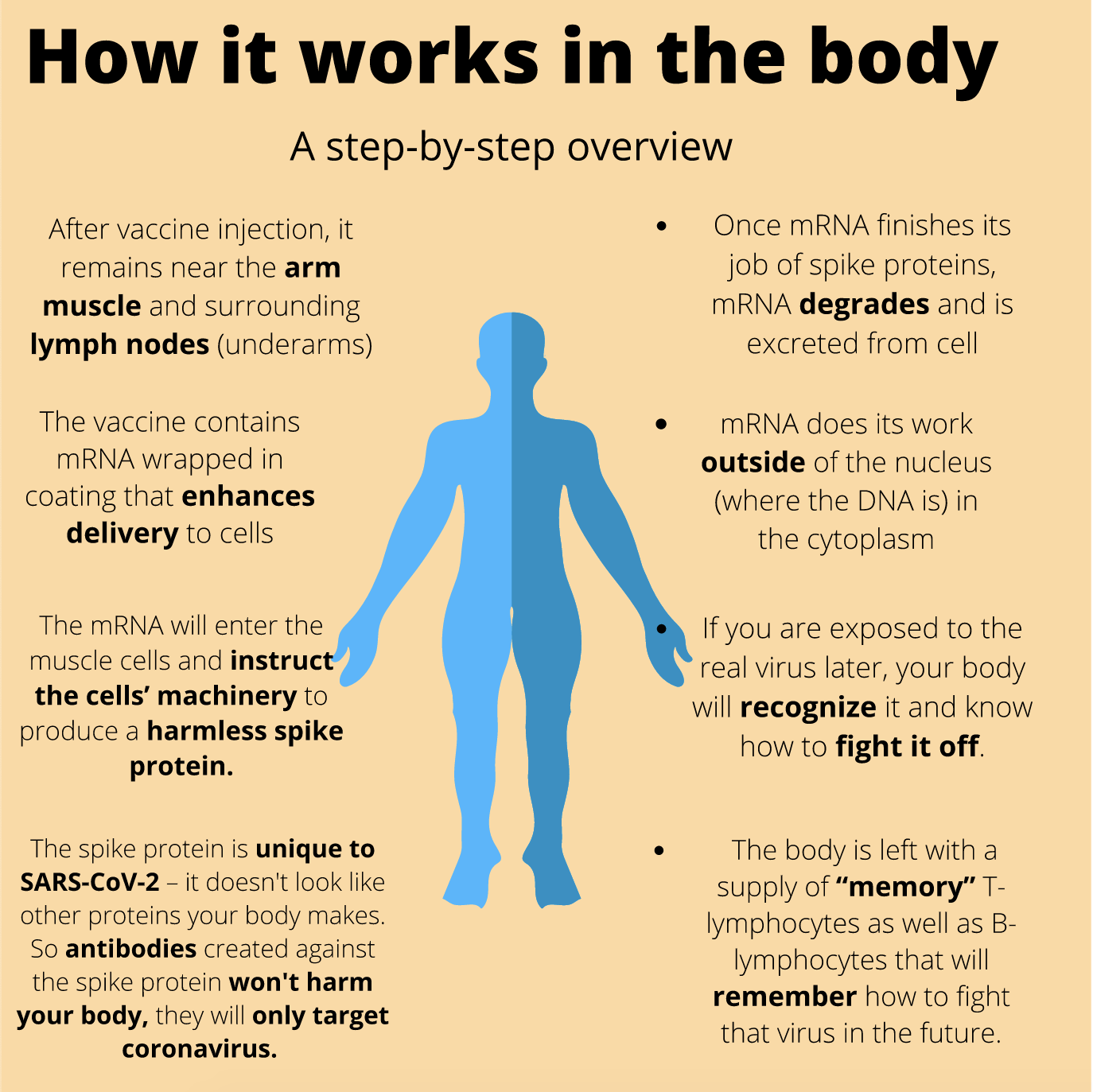

Source: Scientific American, Nebraska MedicineIn the Trenches of Misinformation and Media Polarization…

But institutional trust is not the only facet to confidence in vaccines. Our readiness to take them also depends on sifting through hundreds of misleading and inflammatory headlines and developing the eye for what is true and what is, simply put, fictitious.

Even prior to the emergence of the virus, misleading claims and misinformation have run rampant. It’s part of what cultivated Adolph’s own reluctance and the reason she took Ivermectin to treat her COVID-19 symptoms.

Rovner spoke of the number of factors that contribute to misinformation spread through communities. “People are vaccine hesitant, or accepting, depending on what the people around them think and what their doctors tell them,” said Rovner. “You get it from healthcare practitioners and from friends, neighbors, relatives. There are communities of vaccine hesitancy,” continued Rovner.

Osteopathic physician Dr. Joseph Mercola, who touts natural supplements and berates COVID-19 vaccines for its alleged withheld data, is one of those doctors. He is also infamous for spreading COVID-19 misinformation. “COVID-19 vaccines are the single most overhyped and oversold vaccines in history, primarily because of pharmaceutical and political influence,” said Mercola. Instead of placing the burden of protection on vaccines, he assigns individuals to eliminate all vegetable oils and most processed foods to develop a strong immune system against infection.

“Optimizing your metabolic health creates authentically effective immune resilience,” said Mercola, citing his book Fat for Fuel and Effortless Healing. While stronger immune health typically leads individuals to more robust protection from viral infections, it overlooks individuals with immunocompromised systems or other underlying health issues. For those with such backgrounds, Mercola presupposes individuals maintaining a perpetually healthy state for which would provide them with enhanced immunity and protection against infection.

But things aren’t that simple, especially when it comes to health, and proclaiming those views only perpetuates misunderstanding and distrust in how viruses work. This distrust also leads to echo chambers where unsubstantiated claims foment.

Accumulation of such sources that reflect and reaffirm pre-existing beliefs intensify biases. “We live in a hyper-polarized society and that fragmentation is amplified by all sorts of forces, including social media,” said David Willman, American Pulitzer Prize winning investigative science journalist. “Whether it’s coincidental or causal, the pandemic has probably accentuated this.”

The presence of alternative facts floating in the ether only complicates matters further. Ed Avol, a Professor of Clinical Population and Public Health Sciences at the University of Southern California, noted how this added factor enhances the likelihood of experiencing vaccine hesitancy.

“In recent years, in this country and elsewhere, we have had this emergence of alternative facts: if you don’t like the information you make up your own,” said Avol. “And if people believe it, then that’s another thing to deal with.”

If individuals are provided with information that does not clearly illustrate how it will safeguard their interests or sense of self-preservation, they consequently construct facts that restore their sense of security and help them make sense of their own confusion. To do so, intuition comes into play–a dangerous result of lack of transparency whilst communicating science.

Where’s the clear communication when we need it the most?

The lack of transparency from the scientific community is perhaps one of the most supplanting aspects for combating misinformation and promoting understanding of science.

According to a New York Times article, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) isn’t publishing large portions of the Covid data it has collected, which, if published, could reveal the populations at highest risk and help state and local health officials better target their efforts to bring the virus under control.

Like Adolph, my stepfather Chris Jimenez, who labels himself as vaccine hesitant, also expressed his concerns of lack of long long-term data and unpublished data. “To me, there wasn’t enough empirical data,” said Jimenez. “It was just approved for emergency use, and I didn’t want to take something that would end up hurting people.”

Until my family and I battered him. It took nearly 20 exchanged articles, a few arguments at the dinner table, and some civil discussions scattered in between to encourage him to take the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. He’s glad he did now, though. After getting COVID-19 when he was unvaccinated and remembering his bed-ridden state, he knew he didn’t want to risk contracting the virus again. He cut his losses, for the sake of protecting the family and himself from future risk of contracting the virus.

It’s a conflict that’s been played out in families everywhere throughout the pandemic.

“No long-term effects can possibly be known because these are novel vaccines. Our health agencies are hiding negative data about the vaccines,” said Mercola. He echoed Adolph’s own trepidations. But some level of this safeguarding also stems from the “fear that some of the information might be misinterpreted,” said Kristen Nordlund, a spokeswoman for the CDC.

Nuances to the debate

Perhaps we must consider how, then, to mitigate the possibility of misinterpretation of data. Mostly, because it is counterproductive to the very fear outlined in Nordlund’s argument: it discourages those who are initially hesitant from reaching any level of understanding or confidence in the vaccine and it perpetuates polarizing views.

Our willingness to take sides, to denounce groups with beliefs unlike our own, and to simplify the issue to an ‘us vs. them’ mindset has only inflamed the polarizing debate. It has fostered echo chambers and a disinterest, or in stronger cases, hostility towards understanding differing views.

The debate is much more nuanced than treated, however. Some are strongly hesitant or recalcitrant and others are not attitudinally opposed to the idea of getting vaccinated.

It explains why the percentage of those categorized in the “wait and see” vaccine willingness have decreased over the last two years, and those in the “already vaccinated” group have increased.

Kamal Cheema, business owner of health and wellness company ‘Astron Herbal’, was one of 218 million people in the U.S. to take the COVID-19 vaccine. As an herbalist and formerly practicing physician, she understood the protection that the dose would offer her.

So Cheema got vaccinated.

Still, she contracted COVID-19 after vaccination, a risk that exists, although significantly reduced. It’s referred to as a vaccine breakthrough infection, but vaccinated individuals are less likely to develop serious illness than those who are unvaccinated and get COVID-19.

After recovering from the infection, Cheema experienced long COVID-19. For two months, she was unable to form coherent sentences, experienced an eerie regression to scattered childlike cognition, and got into two car accidents. She attributes these experiences to her impaired cognitive functions. “Three months ago, I couldn’t even draw a clock,” said Cheema.

Her collective symptoms were diagnosed as brain fog. It affects one to two percent of the population after recovery from infection. While she continues to endure the symptoms of post-COVID brain fog, she experiences them much less severely and frequently.

Prior to these encounters, Cheema wasn’t vaccine hesitant. After all, she had a professional degree in medicine. She does everything in best practice as advised by the Center for Disease and Control (CDC): washing hands frequently, masking up, and getting the vaccine. Conducting her own research through a subscription to PubMed, a trusted peer-reviewed journal used by the scientific community, alleviated any gentle apprehensions she had. It was simply another way to solidify her decision as a single mother to get herself and her 12-year-old son vaccinated.

“But going through all of that [long COVID-19] has made me question my initial determination to get the vaccine,” said Cheema. “I don’t think I’m going to go for the second booster, I feel much less confident after what happened to me.”

Cheema nonetheless believes in making space for both eastern and western medicine. It’s what inspired her to create a business that embodies these goals. “After speaking with my father, an herbal producer, we decided to unite the two and create an outlet for holistic health,” said Cheema.

While she acknowledges that maintaining a healthy diet is beneficial, supplemented by her herbal products, she understands the need for more advanced medicine that can offer more robust and targeted protection.

“Having everything healthy is great, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t also be protecting ourselves with advanced medicine,” said Cheema.

This duality of thoughts is not uncommon. Cheema’s experiences have revealed the nuanced nature of the debate, and they create the space for compassion, listening, and understanding. How individuals grapple with their own hesitancy and the awareness for public health varies, but it is a critical aspect of the vaccine debate that is too often overlooked.

What can be done?

So, the question remains: what can be done about all of this?

A study by the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy’s Science, Technology, and Public Policy Program found two main causes of public mistrust: limitations and failures in scientific and technical institutions, and institutionalized mistreatment of marginalized communities.

It is then necessary to enumerate systematic changes critical for promoting understanding and restoring trust in science and the platforms that convey relevant news about COVID-19 and vaccine developments.

Working to restore trust in science and media precedes the ability to reduce incidences of vaccine hesitancy. It is therefore plausible to consider how to effectively and informatively talk about science and COVID-19.

Improving media and science literacy

Media literacy and science literacy are joined at the hip. One cannot exist without the other in order to filter out alternative facts from evidence-based information. Put simply, the world needs to understand how to navigate an increasingly polarizing climate to combat misguided, or even worse, uninformed decision-making.

Willman urges that in order to fully grapple with the news being consumed at hand, especially news that presents purported scientific claims, consumers must ask the question, ‘What is the basis of assertion?’

Of course, this places a level of responsibility, perhaps even a burden, on the consumer to think more critically and to duly challenge the information conveyed. Rovner is one who believes that informed decision-making is guided by being accurate and clear as a journalist. “I try to bring complicated information to lay people and explain it in terms that they can understand,” said Rovner.

Finding ways to detect misinformation is another way to mitigate the spread of inaccurate or groundless information. “There is an inability to tell reliable information from unreliable information,” said Rovner. For consumers navigating news outlets inundated with COVID-19 information, mastering the art of diversifying sources, finding credible information, and checking our own biases is critical to restoring a balanced news climate.

We must also approach science news with an analytical mindset, and the first steps to do so include heightening our literacy in science. “At a fundamental level, it is to find out what’s happening and understand it well enough to be able to translate it in a way that a lay readership would understand,” said Willman.

Avol mirrored these views in how scientists can and should communicate more effectively and powerfully. “It’s a very different setting when you’re talking about scientific results in a conference than when you’re trying to present scientific information and take home messages to the public,” said Avol. “But we have to face up to it and talk about it in ways that people can understand. In the public arena, you want to know: ‘What should I do? What is safe? What do I do to protect my family and my kids? Is this a problem or not?’”

Trust built from transparency

To overlook science communication and its deficits would be omitting a critical feature that helps explain the genesis of COVID-19 confusion. Science and scientific papers are inherently filled with complex concepts and technical language.

In improving the health of public trust in science, scientists should be willing to traverse their comfortable territory to the media where their studies are relayed, expressed Rovner.

By informing the public of scientific processes and insights and keeping us in the know throughout the ever-evolving and lengthy studies that is research, scientists can actively work to promote engagement and more informed decision-making that considers both individual and public health. Their involvement in countering misinformation would also help policymakers avoid introducing harmful policies.

One of the single most important, yet overlooked, facets of scientific inquiry, is its dynamic nature. “Evolving information is a cornerstone of science, but it’s understandably challenging, if not downright frustrating for the public,” said Avol. “In science, some things are absolutes. But [scientists] don’t mind finding out that hypotheses are wrong or need to be adjusted, or that based on new evidence, we need to change them,” continued Avol.

As data continues to be collected about the novel coronavirus and emerging mutations, scientists should illuminate the public that data collection is an ongoing process and hypotheses can be subject to change.

“The way we improve trust is being clear about what the evidence shows; trying to explain it in a way that sort of demystifies what we think we understand. But also explaining that we don’t have all the answers,” said Avol. “We are continuing to do the research and learn more. We learn more about vaccine hesitancy by studying the population who are both hesitant and who are conforming, and then learn something about who is getting sick, who is not getting sick.”

There is a collective interest for scientists and journalists to promote transparency and understanding of science and COVID-19. “We’re all entitled to our own opinions, but we’re also entitled to the facts behind it. So we need that transparency,” said Willman.

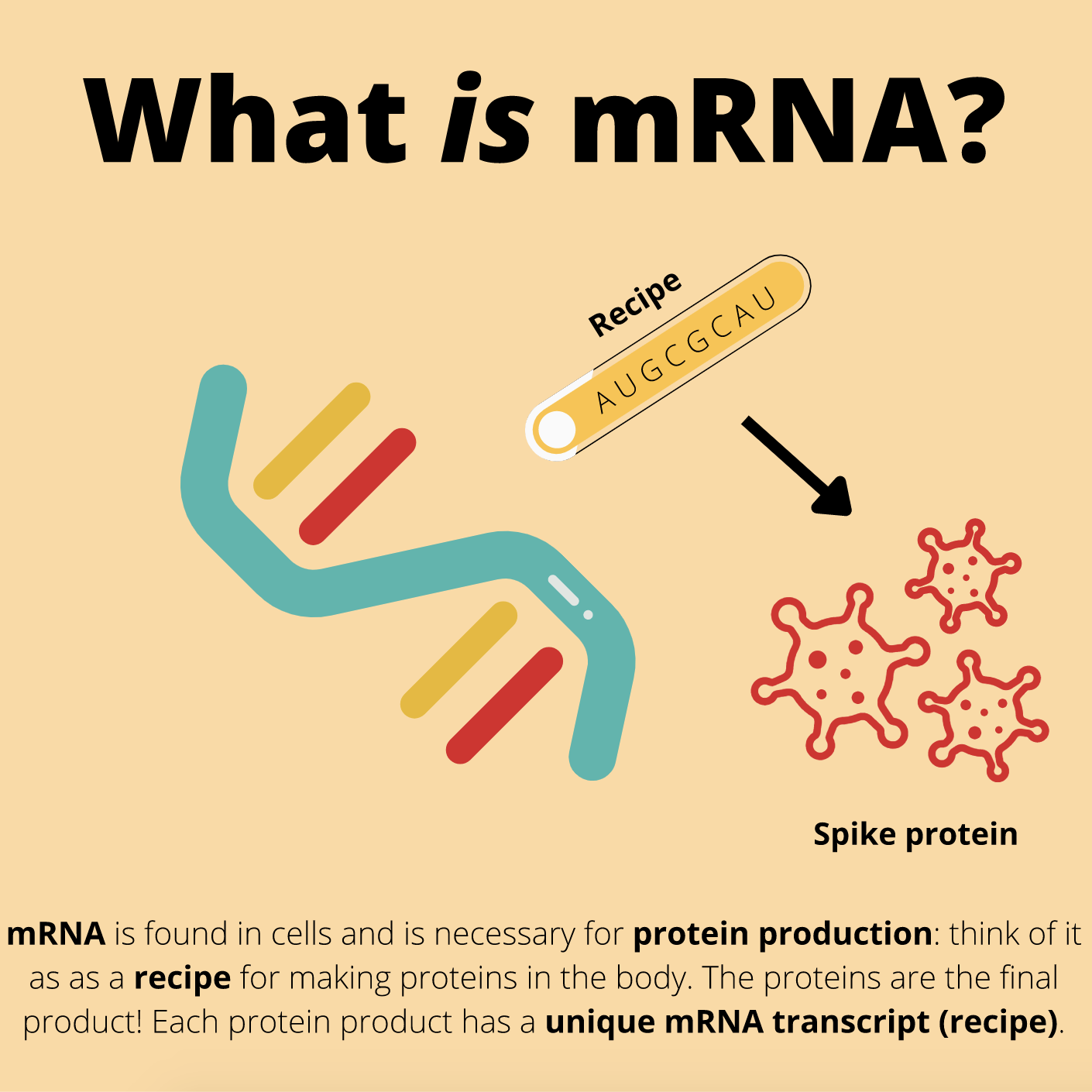

Trust built from transparency also requires clear communication regarding how vaccines work. If a substance is entering the body, people are intrinsically curious about its mechanism of action and its effects.

Making data more accessible by clear and effective communication mitigates misinformation and encourages the formation of opinion-networks. For the public’s sake, greater comprehension in science creates a more informed, engaged, and consequently, healthier society; and with that, comes reinvigorated trust in science and those that convey its news and fundamental discoveries.

It’s a difficult game of balance between awareness, trust, and the ability to fairly question unfamiliar information. But with the help of scientists and journalists, conversations going forward can be more productive and understanding of hesitancies as we continuously learn to grapple with ever-evolving information.

“My goal is to give people actionable, correct information for them to be responsible citizens,” said Rovner, reflecting on her career as a health policy journalist and how she systematically approaches the contentious debate.

As journalists and scientists constantly work to counter misinformation and introduce ongoing evidence-based science, it is also critical that consumers understand the nature of science so that we can deepen our own understanding and ultimately make the most informed and beneficial decisions for individual and public health.

With that, we are left in a much better position for simultaneously managing the current pandemic and preparing for any future public health crises.