Eric Tinkerhess grew up in a family of musicians and learned to play the cello when he was 10. His father and brothers play folk and jazz, but Tinkerhess’ interest has always been in Baroque music. He’s studying for his PhD in musicology at USC; he wants to be a professor and is intent on teaching the importance of early music to students.

“My dad comes from the folk music background of the oral tradition,” Tinkerhess said. His whole philosophy was always sort of opposed to the elite trends of classical music. So I have this inner struggle of why I’m playing this music and should it even be studied and consumed by listeners today.”

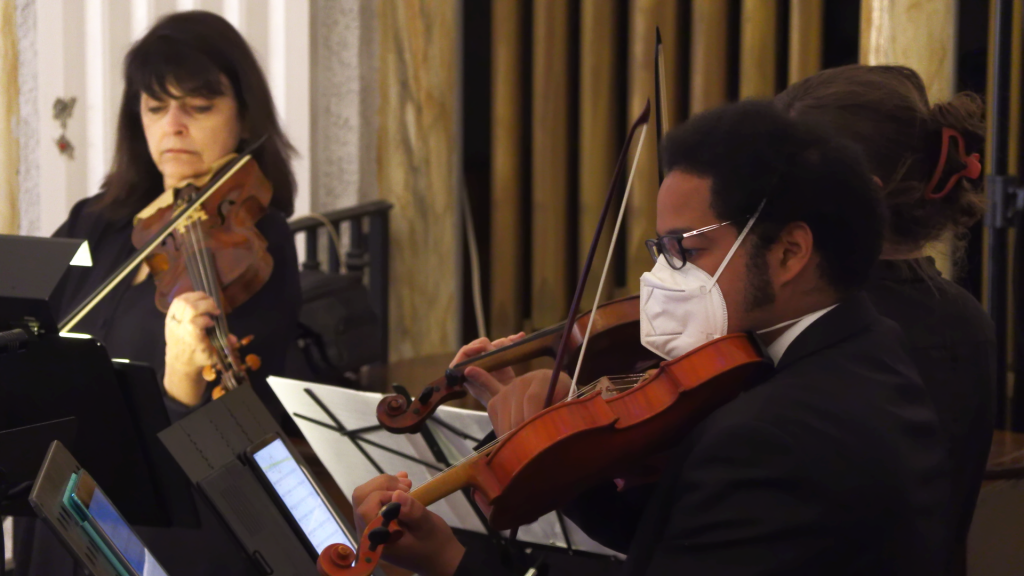

Tinkerhess is one of many Baroque music scholars who is hoping to change the narrative about the aristocratic associations many have with early music. The stereotype of high-brow types in a stuffy concert hall is far from the reality of current Baroque performance, he said. Ensembles like Musica Transalpina, for which he has played cello, perform to locals for free at churches in South Los Angeles. Through music performance and scholarship, Tinkerhess is hoping to dispel the elitist stigma of early classical music.

“I’d like to show how it’s not this stuffy, elitist conception that we have of classical music in general, and that there were a lot of diverse influences on the music,”

— Eric Tinkerhess, Classical Cellist and Musicology PhD candidate

There are indeed many misconceptions about Baroque music, but the historical period containing the works of Bach and Vivaldi is much richer and more expansive than chamber music played for a small aristocratic audience. Baroque orchestra manager Noah Gladstone is hoping to resolve these misconceptions, he said.

“When people hear early music for the first time, without any expectations on what they’re going to see, their only association is the renaissance fair.” Gladstone said. “And that’s absolutely not what it is at all. I think that’s really important for people to know, that you’re, you know, really kind of looking at the prototype for modern music, and even popular music.”

Indeed, it was Baroque music that first laid the foundation for what eventually became modern music. Beginning in the 1600s, composers began to experiment with harmony and dissonance in their arrangements. For the first time in music history, composers structured the melody of the instruments to the lyrics of the song. In this sense, it was the first time that music told a story. Claudio Monteverdi, who was one of the most prominent Renaissance composers, believed that music must serve the text. He is considered the father of opera.

“You’re joining music with action and telling a story. And I think that you can draw a line all the way from this renaissance period to film scoring, to John Williams. In a way, early opera is like an early early movie score: It’s painting pictures for the audience to see in their mind’s eye. No one had heard music like this before — music that’s really evoking the storytelling behind the text.”

— Noah Gladstone, trombone player and orchestra manager

The beginning of early music scholarship can be traced back to the 1940’s and 50’s, according to music composer, producer and professor Peter Rutenberg. This fascination with old music, dubbed music archaeology, began when music fans started digging into attics and storage spaces in churches, where they found old scores covered in dust. From here, the field of musicology started to crystallize. The recovered scores sparked the interest of publishing houses, who disseminated these pieces so that musicians could perform them for the first time in over a century.

“Throughout the second half of the 19th century, and very actively all through the 20th century and, and through today, music historians, music colleges are doing more and more research and, and trying to create the fullest library of early music that they can,” Rutenberg said. “So that’s where we get Baroque music, and there was enough of it to really start becoming fascinated with it.”

Baroque music: A brief history

Then came the advent of broadcast technology. During the latter half of the 20th century, a love for Baroque music was cultivated primarily through classical music radio.

“Everybody that I know was glued to public radio,” Rutenberg said. “I certainly was. I had KUSC on in my car all the time in 70s.”

Rutenberg later worked for KUSC for nearly six years in the 1980s, where he was head of production, and later, a program director. It was the golden age of classical music radio, and Baroque music was more widely listened to than at any time in history. Then, a few decades later, the internet democratized Baroque music listening even more: the best of Bach and Vivaldi were available for streaming or downloading from anywhere with an internet connection.

“There is a handoff, I think, generally speaking from broadcasting to, to Internet,” Rutenberg said. “Because, for example, when I was at USC, there were 350 Classical radio stations in this country. If there are today 50 full-time, I’d be surprised.”

There are between 40 and 70 American radio stations playing classical music today, depending on who’s counting. For young adults who grew up with the internet, radio listening is not the venue of choice. Music enthusiast Ambika Nangihalli grew up playing Bach on piano and regularly enjoys playlists of Bach and other Baroque composers on streaming services. Still, she longs for the delight of seeing the real thing in-person.

“When you go to see a live performance, the aura, or the energy, or the experience you get there from the live music is radically different from watching that concert on video on YouTube, or just streaming it through Spotify, it’s not the same,” Nangihalli said. “And while it does lose that sense of authenticity, it also does something remarkable. it makes it accessible to people everywhere. Somebody in a small homestead in the middle of Arkansas could hear the LA Phil playing something from Bach that they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to go out and get.”

Today, many Baroque ensembles incorporate historically-informed performance, a style of play in which the instruments and style of the music aim to match the period as accurately as possible. This can mean many things, including opting for string instruments with animal gut strings, which are more historically accurate, rather than metal strings, which are less historically accurate. Period instruments allow for more more dynamic shifts between loud and soft, as well as between smooth and staccato. This allowance for precise variations in sound allows performers to bring to life the rich tonal image of the original music.

What is historically-informed performance?

“When you actually read the many books that musicians wrote at the time about how to play their music, it’s very different than how it’s taught today, in conservatories in universities all around the world,” Tinkerhess said. “The main differences are that modern musicians today generally play in a style that was formed in the postwar period, along with modernist architecture and painting, where it’s a very well-rounded form… But in the 18th century, a lot of the books that musicians wrote about how to play their music said there should be a lot of dynamic shading in every measure of the music.”

These historic instruments create a certain intimacy with the audience, Gladstone said. They are not as loud or as brash as modern instruments, but they do allow for more nuance and inflection in their sound. Gladstone describes historically accurate instruments as having a “Sonic palette,” granting them the ability to create distinct shades of sound, rather than sheer volume. Because of this, Baroque music performers have much more room to show their virtuosity than they would be able to on a modern instrument, which is designed purely for creating a lot of sound.

“You’re really getting a window into this moment in time,” Gladstone said. “You’re seeing a lot of these structures and chords and harmonizations being like, ‘Wow, how cool is this to see the very beginning of popular music?’”

Tinkerhess echoed this sentiment. He is drawn to the rich thread of history connecting Baroque to contemporary music, he said.

“[Baroque] music was more similar to the oral traditions of popular music,” Tinkerhess said. “That’s partly why I’m drawn to it: because of the dance rhythms that are even in the elite art music of Bach and other court composers. They were influenced by popular music.”

Today, Baroque and classical music are widely enjoyed in Europe, early music’s birthplace, as popular music. When Tinkerhess moved from his family home in Michigan to Paris to study music at La Sorbonne, he realized that the audience for this music is markedly different in Europe than it is in the US. Even in small towns, there’s music festivals where they play classical music, according to Tinkerhess. The rural population in Europe, he says, learns about classical music from a young age and doesn’t have the same stigma as it does in the U.S. In the U.S., it’s more of an urban audience that enjoys early music.

“In my family, I was the only one interested in classical music. I played in rock bands in high school and jazz bands too, and all my friends listen to hip hop. So in my high school, being a classical musician was sort of countercultural, it was definitely not cool.”

— Eric Tinkerhess, Classical Cellist and Musicology PhD Candidate

Whether or not Baroque music is considered “cool,” there are more people enjoying it than ever, thanks to the internet. Gladstone is hoping to see a better turnout of young people at performances by his ensemble, Tesserae Baroque, he said.

“I think once people come to a concert, it really changes them.” Gladstone said. “They are introduced to this whole new world of music that they never would have even considered because [they think] it’s too stodgy; it’s too old; it’s too boring.”

Ultimately, early music revival will continue due to the dedication of the musicians who transpose their passion into music and through the audiences who are willing to share that passion with them.

“We want to share this music with as many people as we can,” Gladstone said. “I’m hoping that, as people find out about the early music revival, that more people will be excited about this kind of genre of music, because I think it’s one of the most exciting genres there is. You are really being transported back in time.”