Pieces of time

Pasadena artisan carves out future for historic California tilework

By Catherine Orihuela

May 3, 2022

Perched on a stool under the metal awning that covers the driveway, Cha-Rie Tang fidgets with her long dark hair. Silver strands start at her temple and weave through the braid falling over her shoulder. She rubs her hands over her knees, leaving smudges of dust on her pants. Weathered from age and years of work, every line across the back of her hands, palms and knuckles tells a story. A fine layer of ceramic dust covers every surface in the studio, from the workbenches and concrete floor to shelves of plastic bins and cardboard boxes filled to the brim with tiles of every shape, color and design.

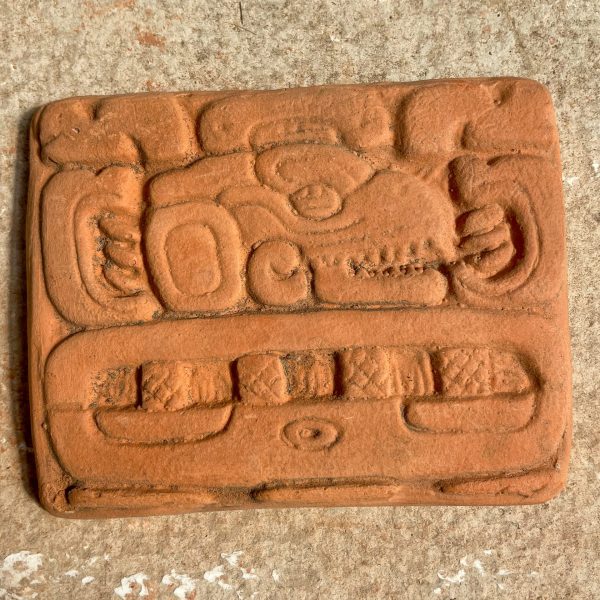

From a koi pond in the back corner of the yard, the sound of rushing water mixes with birds chirping away in nearby trees. But what catches the eye is a long workbench running along the side of the studio, under which are row upon row of red-stained plaster molds. Small decorative tiles hang on nails attached to the fence above the workbench. Turning her small frame on the stool, Tang follows my gaze over her shoulder. These, she tells me, are her prized Batchelder tiles.

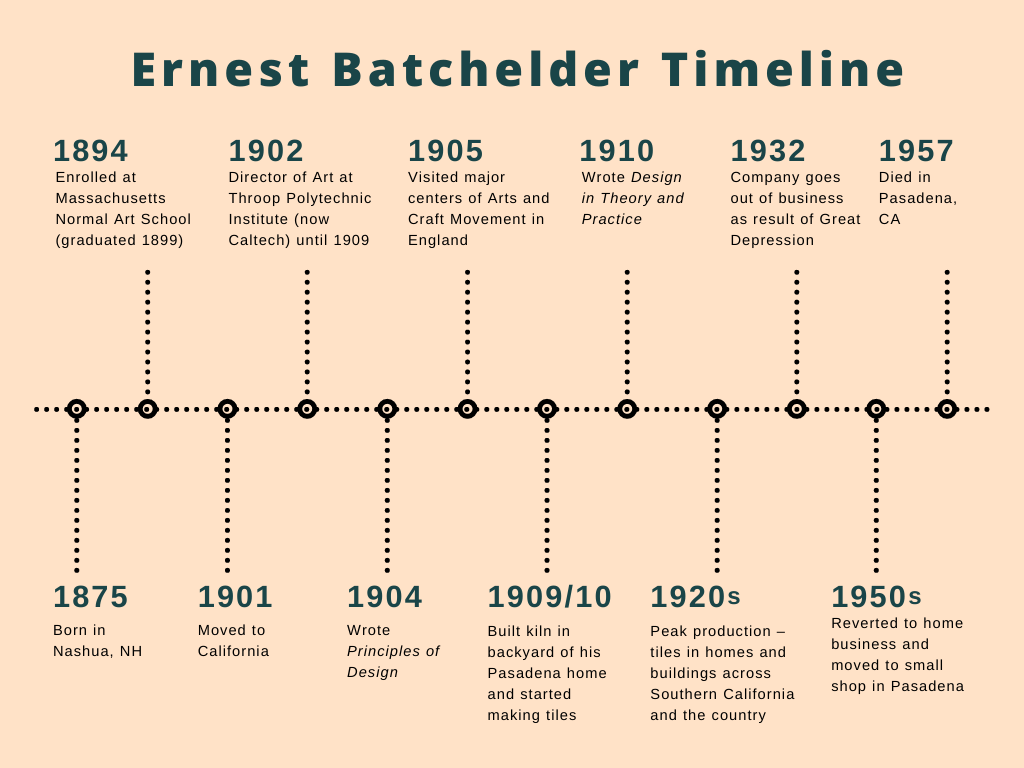

The founder of Pasadena Craftsman Tile, Tang is an artist keeping the legacy of handcrafted Batchelder tilework alive in Southern California. The 70-year-old self-taught tile maker specializes in reproducing Batchelder tiles, a type of decorative tile that was produced during the heyday of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the early 1900s by famed tile maker Ernest A. Batchelder. A reaction to the industrial age, the Arts and Crafts Movement fostered an appreciation of handmade objects. Once considered strictly ornamental, crafts like tile making, pottery, furniture making and weaving were elevated to the status of high art generally reserved for painting and sculpture. In addition to these reproductions, Tang also makes custom hand carved ceramic pieces.

Handmade tiles are displayed on a fence at Tang’s studio in Pasadena. (Catherine Orihuela | Annenberg Media)

“People have continued to find rewarding experience in making something of their own and to me the whole tile piece fits right in that picture.”

Sue mossman, executive director of Pasadena Heritage

Batchelder tiles are known for their natural and geometric motifs set against a warm earthy background and covered with a blue or other cool-toned glaze. Used as decorative accents, Batchelder tiles are most often found on fireplaces and fountains in original Craftsman homes.

Southern California is a region steeped in a rich history of Arts and Crafts design. Countless buildings and homes throughout the greater Los Angeles area are adorned with exquisite Arts and Crafts tilework and yet most people pass by them every day, unaware of their historical significance. With additional difficulties faced by aging craftsmen in passing their skills on to younger artists, crafts worldwide face the threat of becoming endangered or extinct and it has fallen to artists like Tang to preserve this history and pass on their knowledge to future generations of craftsmen.

To understand why people should care about the future of handcrafted tilework, one need look no further than to one of the principle tenets of the Arts and Crafts Movement: The act of making something for yourself, by hand, is enriching to the personal spirit of the maker. Having people devote their time, bodies and minds to the act of creating—however perfect or imperfect—was central to the Arts and Crafts ethos.

“Embracing the idea, the concept, the vision that handmade things have value, and beautiful handmade things have intrinsic quality, is very satisfying to the human soul to see, use and feel. So I wish that we could all take time away from looking at screens to go make something,” said Sue Mossman, the executive director of Pasadena Heritage, a non-profit historic preservation organization that has been operating in the city for nearly half a century. “People have continued to find rewarding experience in making something of their own and to me the whole tile piece fits right in that picture… It feeds your soul and gives you a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment.”

A brief portrait of the artist

Here is a short introduction to Cha-Rie Tang and the work she does as a tile maker living and working in Pasadena, California. Get a glimpse of her Batchelder tile reproductions as well as her custom carved pieces.

Introduction to craftsman style

Born in Taiwan, Tang came to the United States with her parents when she was 10 years old. Growing up in Lexington, Mass. with her five siblings, Tang always knew that she wanted to be an artist and went to MIT to study architecture. After college, she moved to Pasadena with her husband, a PhD candidate at Caltech, in the early 1980s. She quickly fell in love with the city, not only for the climate and culture and being able to have flowers all year round, but also because she was introduced to Pasadena’s iconic Arts and Crafts homes.

In those early days, Tang would take out her sketchbook and draw houses from her neighborhood, and quickly discovered Craftsman-style architecture and tilework. Her introduction to Craftsman tile came at a time when many Pasadena homeowners were destroying or covering up the original tilework in their homes.

“Every house had a Batchelder fireplace,” she recalled. “But in the early 1980s, people were tearing their Batchelder fireplaces out. And so I got into tiles and learned all about Craftsman tiles, and slowly… I accumulated a lot of designs.”

Buried treasure

She has come by her designs in unusual ways. For example, a friend told her about a local coffee shop on Raymond Street that had a Batchelder fountain. She went to the coffee shop under the cover of darkness with some clay, and pounded it into the Batchelder tiles to get impressions of the designs.

“I do things like that,” she says chuckling.

But even more remarkable was when a friend of Tang’s unearthed a buried collection of original Batchelder plaster molds from his backyard.

Chris Casady bought his home in Silver Lake in 1991. The animator and visual effects specialist, known for his work on the Star Wars films, had been in the house for about a year and recalls doing landscaping work when he discovered that the retaining wall in his backyard was made out of some strange, oblong white blocks. The blocks were eroded on the back, but when he turned them over and brushed off the dirt, Casady was surprised to find intricate designs carved into the surface. There was no mistaking it — these were plaster tile molds.

With the help of his girlfriend, Becky, he pulled dozens of these plaster molds out of the dirt and even found an entire mantelpiece. Casady knew nothing about Batchelder at the time, so he took them to the Ann Sacks tile shop in West Hollywood. They were quickly identified as original Batchelder tile molds.

A few years later, in the mid-1990s (neither Casady nor Tang can recall the exact year) Tang was coming back from a family vacation in Snowmass, Colo. with her husband and two young kids. As luck would have it, while there she had taken classes in slip casting, a technique that involves pouring liquid clay into plaster molds to produce pottery and other highly detailed ceramic pieces.

At the time, Tang and her husband were digitizing and publishing 19th century design books on CD-ROMs. Casady had purchased their CD of The Grammar of Ornament, an 1856 catalog by Owen Jones of cultural designs, styles and motifs from around the world. He quickly became acquainted with Tang, and ultimately told her about his discovery.

Tang immediately wanted to come over and take impressions of the molds. With materials in hand and her new skills in slip casting, she spent an afternoon at his house making tiles from the molds. She would later go on to make her own molds from some of the originals.

Tang’s tiles that she cast from Casady’s original plaster molds

At the time, Tang and Casady learned that a standard four-by-four-inch Batchelder tile could be worth upwards of several hundred dollars. When they took their tiles to Mission Tile West, they were sure they had struck gold. But the owner told them that while they could sell a few of the tiles, what they really needed were the accompanying field tiles, because homeowners want to do an entire project and not just purchase one decorative tile.

“I was a little disappointed because I was not ready to be a fabricator of tiles,” Tang said. “I imagined that was going to be [a] really, really big commitment.”

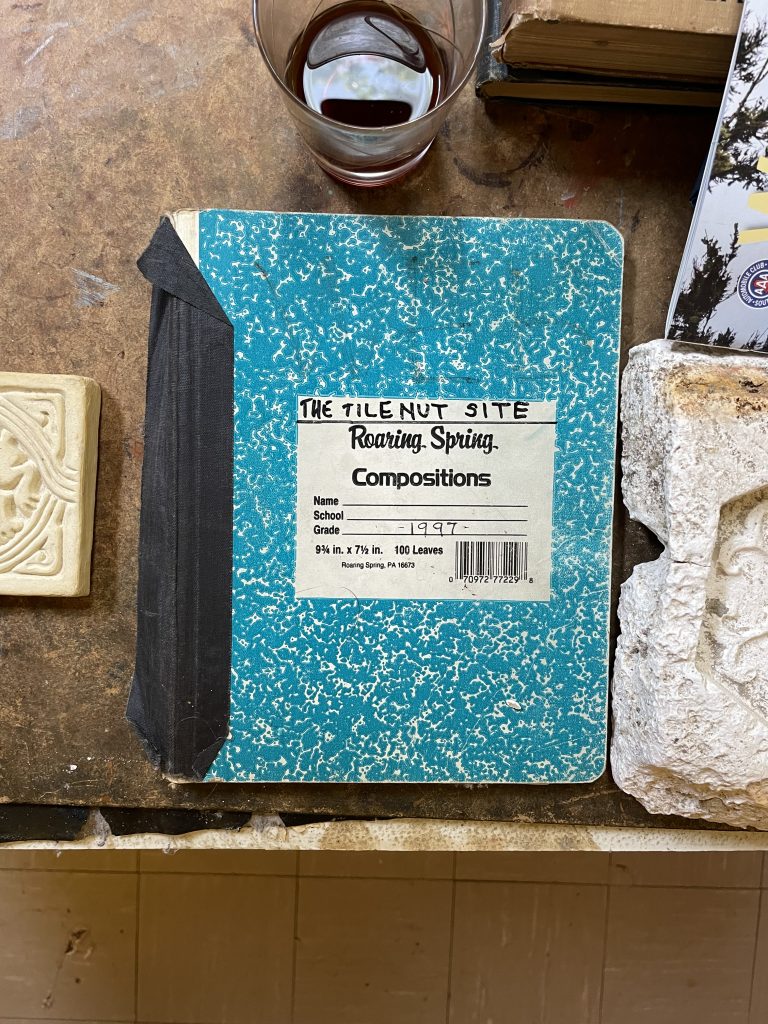

Casady wanted to learn more about Batchelder, but because the internet was so new then he could not really find any information online. After playing around with the molds for a year and reading as much as he could, a whole new world opened up to him—and so began his love affair with Batchelder tile.

After about six years of research, Casady decided to launch his own website dedicated to Batchelder in 1997, called “Tile Nut.” As Casady puts it, the website is his way of celebrating Batchelder’s contributions to Arts and Crafts design.

The original notebook Chris Casady used to plan out the “Tile Nut” website in 1997. (Catherine Orihuela | Annenberg Media)

Along the way, Casady also did some digging into the history of his house and consulted with Tim Gregory, an architectural historian and archivist known as “The Building Biographer.” Casady was keen to learn how the molds came to be in his yard—he had a strong feeling that there must be some connection to Batchelder, and he was right.

Gregory discovered that a building permit had been taken out in 1939 by one Andrew H. Anderson. It turns out that Anderson was the accountant and bookkeeper at Batchelder’s tile factory. After the factory closed in 1932, Casady suspects Anderson must have gone back to the factory and taken the molds to use as building material for the house. Since the tiles had passed out of fashion, Anderson likely believed the molds were worthless and would be more useful as material for his retaining wall.

Tilework journey

As Casady dove deeper into the history of Batchelder, Tang rolled up her sleeves and spent the next 10 years perfecting her tile technique and another five learning how to make her own glazes. From trying to find manufacturers and sellers to creating the actual product, there was a lot of trial and error during those years. But as she puts it, she was just having fun learning something new.

Around this time, Tang also started working on commissions for public art projects. One of the most notable projects was the Metro Gold Line extension in Monrovia, into which she incorporated reproductions of Batchelder tiles.

“My concept was [a] river of time, because the Monrovia people were really proud of their architecture,” she said. “Lots of it was Craftsman. And I thought I could use the Batchelder tiles, and in fact all historic tiles. I made impressions of those tiles and put [them] in the train station… to signify the passage of human time.”

Even though Tang had gained more confidence in her technique and become more savvy about the tile business, she kept her Batchelder work a secret because she was worried about potential copyright issues. After a copyright expert at ArtCenter College of Design advised her everything looked alright, she paid a visit to Robert Winter, an architectural historian who wrote a seminal book on Batchelder tiles, to get his opinion.

“He lived in the Batchelder House in Pasadena, and was a real nice guy,” she recalled. “And he said, ‘Oh, well, let me introduce you to the grandson of Ernest Batchelder.’ We talked and he said, ‘Oh this is great, you do good work. Please go ahead and continue doing this. Just as long as you don’t make things and pretend they were original Batchelders.’ Which was no problem.”

This seal of approval, coupled with the fact that she had access to the original molds and a large design collection to draw on, gave Tang the confidence to go forward with her tile business.

“So I came out,” Tang says laughing. “[I] started making these reproduction tiles and I was able to make field tiles.”

Right off the bat she landed two big commissions. The first was for a custom fireplace at the Robinson House, a Greene & Greene home in Pasadena. The homeowners, Phaedra Ledbetter and her husband, Mark, were so pleased with her work that they also had her design a fountain.

“It’s just so inspiring for both of us to be in her space and to be able to work with her,” said Ledbetter, an interior designer. “She was very open to all of our ideas, which is unique for an artist to be… She wasn’t sort of stuck on her own agenda.”

Tang’s second project was a fireplace for Isabelle Greene, the granddaughter of Henry Greene. Henry and his brother Charles famously brought Arts and Crafts architecture and design to Southern California in the early 1900s. As a teenager, Greene toured houses built by her grandfather’s firm and fell in love with Batchelder fireplaces. When Greene and her husband purchased property in Santa Barbara in 2003, the architect and landscapist was determined that the centerpiece of her home would be an enormous fireplace incorporating some Batchelder tiles.

“The Greene & Greene name just goes with Batchelder tile,” Greene said.

After the renovation was completed, Greene held a housewarming party and was thrilled when Tang attended. As Greene puts it, for a long time she was only familiar with the tiles themselves. It was not until the housewarming party that she got to truly know Tang. The two have stayed in touch over the years and Greene finds her to be a very inclusive person, who always keeps her up-to-date on her family and work.

“What a gal,” Greene said.

Greene loved her grandfather and his philosophy when creating: He aimed to get the best results, not the most money. Tang also takes pride in her fair and reasonable pricing. Like Batchelder, she markets her tiles to people in a very economical way, so that everyone can experience the beauty of Batchelder tile. While she may have some wealthy clients, she tries to make her work as accessible as possible.

“I’m not doing Trumpian mansions. I’m doing bungalows for the common person,” Tang said.

Such a commitment not only to Batchelder’s original designs, but also to his business model, speaks to the continuity Tang is hoping to achieve with her work.

A labor of love

These early projects gave Tang a great deal of confidence, and she slowly began to build her customer base. Commissions came in from across the country which then allowed her to do more advertising for her business. As a result of the recent pandemic, Tang said she now receives several inquiries every day on her website and has even had people reach out asking if they can volunteer to work with her.

In the past, Tang has typically turned down these requests because it takes so much time and effort to teach someone. But now that she is past retirement age and still working 16 hours a day, she is more and more receptive to the idea of having some help around the studio. Her daughter, Mei-Ling Hubbard, who is a partner with her mother in the company, will likely be the one deciding the future of Pasadena Craftsman Tile.

Tang has also had reservations about apprenticing someone in tile making because she does not think that young people know how hard a craftsman’s life can be. One student at a women’s college back East reached out to Tang expressing interest in getting into ceramics, and Tang sent her a very frank response.

“I told her bluntly of my 35 to 40 years in the field [and how] it’s only [in] the last five years that I’ve made any significant money,” Tang said. “And all my friends have retired. So this is a work of love and persistence and you probably need some support along the way.”

The woman never replied.

Tang has had at least four or five apprentices in the past but none of them have worked out. However, she has high hopes for her current studio assistant, Pilar Tena.

“Eventually, if she learns enough, the tile thing might [take off] or the other way around,” Tang said. “But I think for this woman, it’s going to work out because she is interested and she’s willing to learn slowly.”

“[There are] so many homes in Pasadena and throughout the area that hold these pieces of time. And that’s something I’ve always appreciated about Los Angeles homes.”

Pilar Tena, tang’s studio assistant

The 39-year-old artist started working for Tang back in November after a friend who had worked for Tang suggested she look into the job. Tena’s background is mostly as a two-dimensional artist with some ceramic experience picked up during her undergraduate years at the Art Institute of Chicago. But from a young age, Tena has loved all media and jumped at the chance to explore tile making.

“It’s just been incredibly eye-opening, and fascinating and important because [there are] so many homes in Pasadena and throughout the area that hold these pieces of time,” Tena said. “And that’s something I’ve always appreciated about Los Angeles homes.”

As a studio assistant, Tena juggles responsibilities from mixing and applying glazes to prepping tiles and learning how to slip cast. Tena has not made any Batchelder tiles yet but has spent some time cleaning some of Tang’s smaller casts. For Tena, being a witness to this continuation of historic craftsmanship and artistry is a truly special experience.

Tang’s “watercolor” field tiles, as she calls them, come in a variety of blue, green, teal and jade hues. (Catherine Orihuela | Annenberg Media)

When asked if she sees herself committing to tilework for the long term, Tena was hesitant to answer. Before the pandemic hit, she had just received her Rolfing certification and was committed to pursuing her practice full time. But quarantine and social distancing put a pause on that career path, so she pivoted. With the world seemingly back to normal, Tena is unsure how far she will go with tile making.

“I have a great appreciation and respect for the whole practice and proliferation of craftsmanship in general. I want to support and help that world as much as I can,” Tena said. “But I also feel like it’s a great position for someone that wants to specifically continue in that lineage.”

An uncertain future

Knowledge is the key to the survival of Batchelder tile. While it is clear that people like Tang and Casady are among those who know a great deal about it, without support from the next generation, it will eventually be forgotten and destroyed. This was a sentiment echoed by many of the people interviewed for this story.

Arts and crafts design, and Batchelder tiles specifically, are an interesting blip in the arc of design, Casady says somberly. For handcrafted tile to survive, younger generations need to appreciate it and preserve it. Especially in Los Angeles, a city infamous for destroying its architectural heritage.

The act of making is why Tang has found such satisfaction in reproducing Batchelder tiles rather than restoring them. Instead of painstakingly filling in and touching up original tiles—a different labor of love—she prefers going through the entire tile making process from start to finish, taking pride in the fact that her tiles have a more personal touch. While her reproduction tiles may not have the exact depth and definition of the originals, or the same exact coloration, this is precisely how she wants it to be. Tang does Batchelder reproductions to foster the appreciation of tilework in new homes with new homeowners.

At first, Pasadena Heritage’s Mossman had a slightly negative reaction to the concept of reproducing Batchelder tiles. But over time and through the experience of watching her husband meticulously reproduce his own version of Stickley furniture from original documents, photographs and measurements, she has learned to embrace the concept of reproduction when done authentically.

For Mossman, Tang’s ability to meticulously recreate Batchelder tiles and their unusual glazes is an impressive feat, and she praises the artist for her commitment to recreating and paying homage to the originals.

“It is a re-production, not a cheap imitation,” Mossman said. “And because the Arts and Crafts Movement has so many aspects to it… there were many different artistic expressions that came to light in the country in the early 1900s.”

Mossman has served as Pasadena Heritage’s executive director for 28 years but has worked at the organization for over 43, proudly stating that she was the second staff person hired. With the organization now in its 45th year, Mossman says that her life is forever woven into the institutional history of Pasadena Heritage.

She first met Tang at Craftsman Weekend, an annual artists exhibition hosted by Pasadena Heritage, and recalls Tang as being rather shy and reserved during that first meeting. But over the years, Mossman has gotten to know the depth of her talent and dedication to her craft. Though still modest and quiet by nature, Mossman explains that she has a distinct intensity and is a very charming woman.

“She has grown not only in her artistic world, but in her ways of communicating the intensity of her experience, her artistic life,” Mossman said. “So today, she’s much more expressive and forthcoming about what she does and how she does it, and what inspires her, and how she developed her skills, patterns, glazes, and designs than she was in her early days.”

In Mossman’s experience, this is an uncommon quality among artists she has met who often feel that their work speaks for itself. Finding the words to describe their art is often a secondary consideration. Mossman sees Tang as an exception in that both the artist and the work convey the significance of the craftsmanship with equal enthusiasm.

Mike Devlin, a furniture maker who lives and works in the Bungalow Heaven neighborhood close to Tang, echoes Mossman’s sentiments.

“You get this glimpse into what’s going on in her head and her life,” Devlin said. “She’s very generous in that respect.”

Devlin also met Tang at Craftsman Weekend where they were both exhibitors. Seeing that he had a tile-topped table on display, Tang introduced herself, saying she could offer him better pricing with higher-quality tiles. Since then, the two have collaborated for at least a decade, and Devlin has found it immensely rewarding to work with another one-person operation.

“She’s pretty unparalleled as an artist,” Devlin said. “You just look at her work and you can tell that it’s amazing stuff.”

Though many years have passed since their first meeting, Mossman will always be struck by the artistry and craftsmanship of what she does. There is a subtlety and warmth in Tang’s choice of color and subject matter that draws her in and fosters a connection.

“A piece of her tile takes you beyond the tile to sort of feel the inspiration behind it, whether it’s the colors that speak to you or how the glazes are applied,” Mossman said.

Tang’s legacy

If Cha-Rie Tang is certain of one thing, it is that she will continue her tilework for as long as she can. She lives and breathes her work, and her studio environment, with its lush greenery and beautiful scattering of tiles, is the perfect encapsulation of the world she has built for herself. Nature and art coexist in this ecosystem, and Tang is at its center, maintaining balance and keeping the craft alive.

“It’s like [she’s] a butterfly… [floating], doing this and then she’s doing that to keep it functioning,” Tena said. “It’s second nature to her and it’s also just part of who she is and what she loves. And it’s really special.”

Carrying on traditions is no easy task. Tang certainly hopes that handcrafted tilework remains a viable craft, but she does not think that many young artists will commit to tile making to the same degree that she has.

The future of handcrafted tilework, like so many other crafts, remains uncertain. Tang may find a suitable successor who will dedicate themselves to the work and lifestyle of a tile maker, or she may not. There may be generations of tile makers who come after her who continue to create Batchelder reproductions, or she may be the last.

But life has a funny way of surprising us. Call it luck, serendipity or a happy accident—discovering a cache of long lost tile molds and using them to revive a historic method of tile making is something few, if any, people could have predicted. It is a remarkable story and proof that anything can happen in life and that art will find a way.