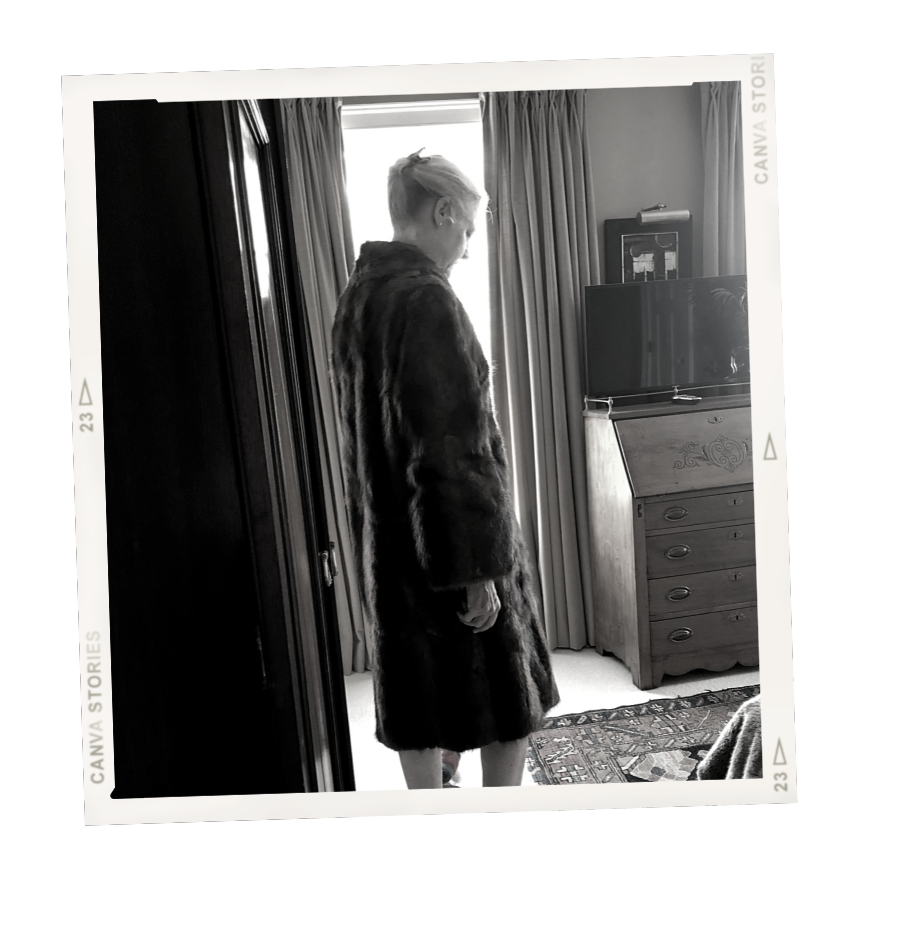

My first experience with family heirlooms moved me to tears. When I was eight years old and in a short-lived vegan phase, I would cry when my mom, Louise Corish, heaved her mink fur coat out of her closet. It only appeared on special occasions – a night out in New York City or a particularly chilly Christmas Eve Mass – but I dreaded watching her don the pale brown fur and accompanying pillbox hat.

My mother did her best to assure me how unique the object was and encouraged me to look past the furry creatures who died for glamour. It belonged to her mother-in-law, Cys Corish, who passed it on so it could (ideally) see the light of day more. But, in her infinite wisdom, Cys said that the set was befitting of a woman who possessed “the proper grace” to wear it, so it bypassed her two biological daughters and went straight to my mother.

I got over being vegan and grew attached to the coat myself, still eagerly awaiting the day it’s passed on to me. In the meantime, I scored a placeholder dead animal for $25 at an estate sale. It’s not as glamorous, less mink and more Manhattan subway rat, matted from age and riddled with cigarette smoke, but the owner was a longtime ballerina, which was enough grace for me. My friends and I take turns wrapping ourselves up in it before smoking out on my rooftop, adding our fumes to its folds.

The coat is also how I met Kim Hutchinson, the eponymous owner of Kim’s Estate Sales. Hutchinson dedicates herself to giving peoples’ treasured items one last hurrah and hopefully one more home. The fur piece belonged to Miriam Marken, a longtime Angeleno who died in September 2021. Hutchinson handled her estate sale, transforming the cluttered home into a bonafide ballerina showcase. Walking through the space, I felt Marken’s presence. Her dance memorabilia was thoughtfully interspersed with family photographs; Hutchinson curated the whole space with intention.

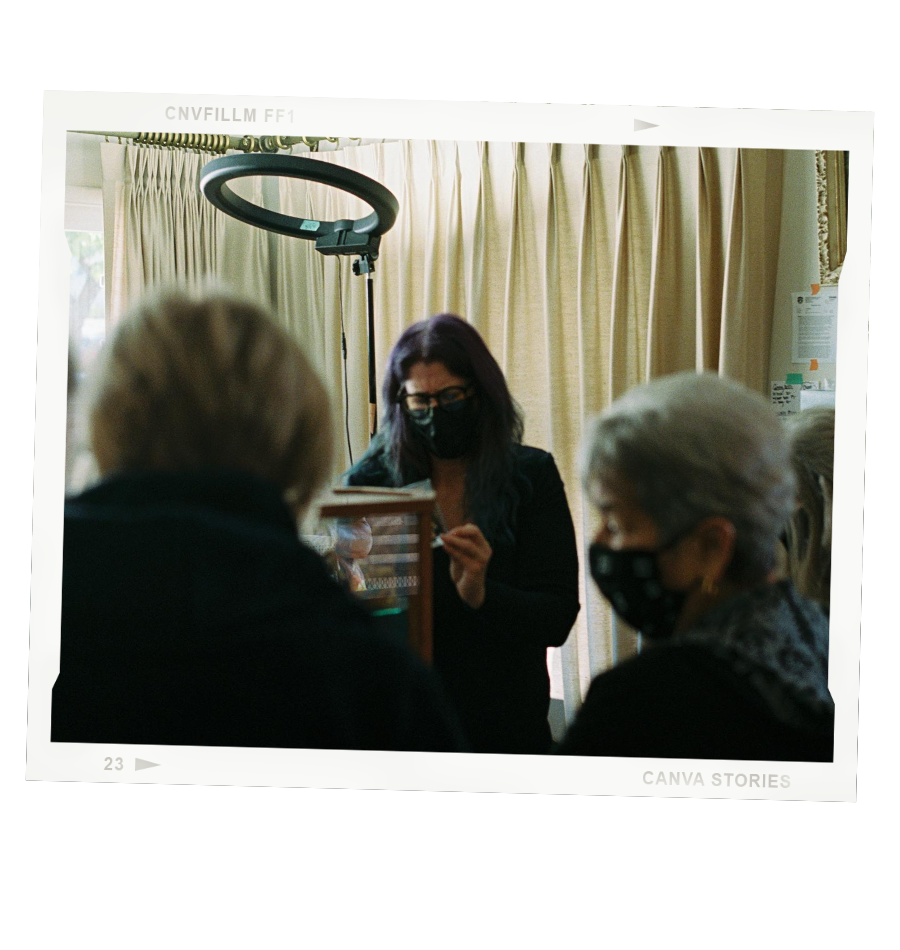

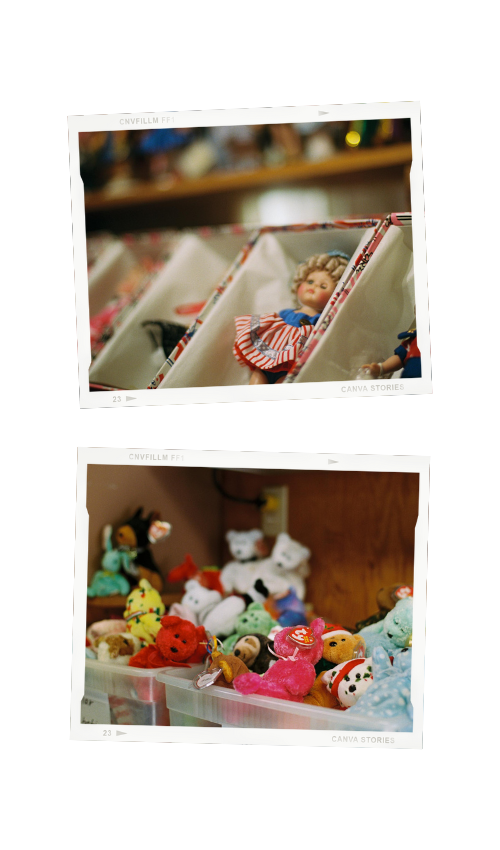

Whether dealing with a collection of vintage toys or hundreds of ballerina figurines, Hutchinson sets herself apart in the Los Angeles estate sale scene by carefully curating her client’s homes.

“No one does it like Kim does,” Teal Fink, one of Hutchinson’s dedicated assistants, told me during my first visit to one of her sales in Burbank, CA. “It’s not like she sees these sales as a chance to offload junk,” Fink says, “she makes her sales an experience for the customer.” If some estate sales are presented as if the owner just up and left, Hutchinson’s are organized like a museum – tidy and on display.

“When you die, I’ll know all your secrets,” Hutchinson says. “That’s not a threat; it’s a promise because I leave nothing unturned.”

A former interior designer, Hutchinson “[puts her] past life to use” by employing her expert vintage furniture and design knowledge. She says that cliché as it is, people don’t know that their “trash” is undoubtedly someone else’s “treasure.”

“I’ll get clients who try and ‘help me’ by clearing out stuff they think is worthless before I get there… I’ll freak out and start digging through their garbage,” Hutchinson says. “I found vintage bed linens in a dumpster last week, and the homeowner’s daughter was like… ‘Really? You can sell those?’ I said, ‘I have a guy who lives for these,’ and sure enough, he came and bought the whole lot before we even opened.”

The estate sale scene is an ever-growing industry, as indicated by annual reports conducted by estatesales.net. From 2017 to 2021, the average total gross sales for an individual estate sale increased by 67%. In 2018, Carol Madden, the former editor of Estate Sales News, predicted we would see a rise due to a shrinking average household size combined with a surge in consumerism. In other words, we’re still collecting things, but we have fewer family members to receive them after we go.

My roommates and I stumbled upon the Los Angeles estate sale scene in early 2021 out of a two-fold need: to get the hell out of our empty (yet cramped) apartment and to find furniture to fill it. We quickly learned that this weekend activity wasn’t for the faint of heart. People gather outside of sales early to put their names down on paper lists, determining who gets to enter the treasure trove first.

The most aggressive early birds are resellers searching for jewelry, clothing, or furniture that will turn a quick profit on eBay or similar platforms. Even as we visited different sales across the city, we saw the same faces – it’s a tight-knit, cutthroat community. If you can’t take the heat, get out of dead grandma’s kitchen.

Hutchinson’s sales speak to this exclusivity. They are by appointment only, and buyers text her to secure their spot in line. Most of her clients are repeat customers, so she’ll send out an email and text alert with photos of the sale beforehand. She’ll also list her sales on estatesales.net, which is how I discovered her. After sending out the general sale blast, she might follow up individually with customers she thinks might have an extra interest in specific items.

“I have real relationships with most of my people… I know who’s going to complain about my prices, who’s a reseller, and who’s into all that haunted s***. It’s an unruly, partnership-driven industry,” Hutchinson adds.

Buyers come with a range of agendas. Some seek out rhinestone jewelry, and others search for vintage cookware. One client of Hutchinson’s, in particular, seeks out old yearbooks (fittingly, she refers to him as Mr. Yearbook).

“If there’s someone famous in there, they could get hundreds, if not a thousand or so dollars for it on eBay,” Hutchinson says. “I always text him first when I find them in a house.”

“That’s as LA as it gets,” chimes in Skylar Combs, another of Hutchinson’s helpers and Fink’s boyfriend.

According to her clients, an organizer like Hutchinson is a rarefied gem. Estate sale companies vary in technique and quality because the industry is largely unregulated. There is no formal license or training for estate liquidators. Still, organizations like the American Society of Estate Liquidators exist to raise industry standards by, as said on their website, being “a trusted resource to consumers and professionals alike.”

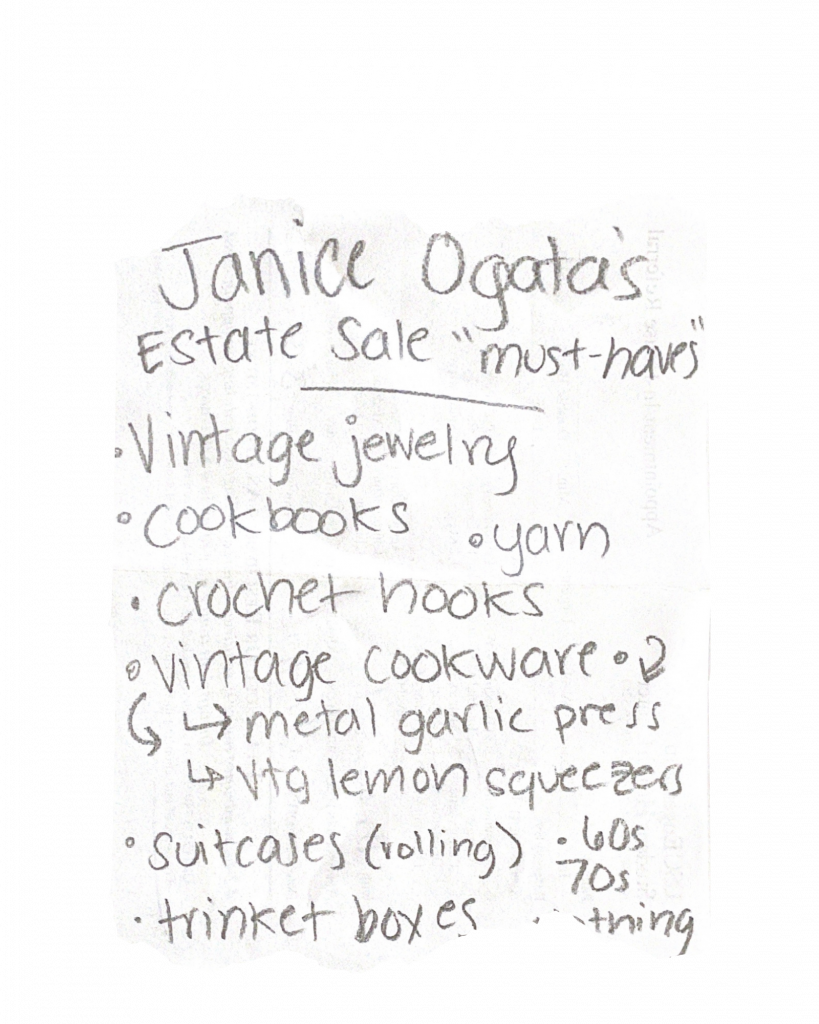

An LA-based artist and writer, Janice Ogata is one of Hutchinson’s self-proclaimed “biggest fans” because of her attention to detail. We met at a sale in La Crescenta, where she was so passionate about Hutchinson’s work that she chased me down the street to talk to me after she heard me chatting with other customers.

“What I admire and appreciate about Kim is how she tags each of the items with prices, which I know takes time,” Ogata told me, adding that “[Hutchinson] always texts me to let me know when she has stuff she knows I’ll love, like these rings.” She gestures to some pink rhinestone pieces in her clear tote bag, “a must” for stricter estate sales, she instructs.

Ogata says she’s “a sucker for a good sentimental piece.” Like my future mink (or current subway rat) fur jacket, she looks for things that remind her of her family, whether it’s a sterling silver charm that reminds her of her late stepfather or mixing bowls reminiscent of ones her grandmother used to own.

In his essay “Why We Need Things,” psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says that “objects reveal the continuity of the self through time, by providing foci of involvement in the present, mementos and souvenirs of the art, and signposts to future goals.”

He distinguishes between two kinds of materialism: terminal materialism, which is rooted in wanting things in the shallow sense, like to impress someone (or to resell on eBay), and instrumental materialism, where “the object is simply a bridge to another person or to another feeling.”

Like Ogata, I love that my items have a story behind them. Ogata tells me that a sense of accomplishment comes from getting that one great score – “it’s really like a treasure hunt,” she says.

We also find joy in watching others luck out – social media accounts centered around second-hand items are rising in popularity. Chasing that high is becoming a mainstream pastime.

See TikTok accounts like @blazedandglazed (real name Macy Eleni, 385.5 thousand followers), a self-proclaimed “thrift queen” who lives to show her followers her latest finds, or @estatesalefreaks (Amy Solomon, 40.7 thousand followers), who posts reviews of LA estate sales.

Social media might be fueling a rise in their popularity; As of May 2022, #estatesale has over 125 million views on TikTok. Like me, Eleni discovered the joy of LA estate sales during the pandemic when she was trying to furnish a sparse apartment. She said that her first few TikToks about the events went viral and that many of her followers had not heard of them. A representative from estatesales.net reported an increase in app downloads in late 2020 when Eleni’s videos first rose in popularity.

In a 2020 interview with Nylon Magazine, Eleni said some companies attribute her videos to a shifting estate sale attendee demographic. “They’re like, ‘We’ve never seen a turnout of such young people that are finding your videos in LA and coming to estate sales,’” Eleni recounted.

Shopping second-hand is becoming a trend in itself. According to a resale industry report published in 2021 by the online consignment store ThredUp, these young people are driving the second-hand market, driven by “the thrill of the find.” The study places a $36 billion evaluation on the industry and projects that will double in five years.

That thrill comes from finding unique pieces that set the buyer apart from their peers, says Solomon. People are getting tired of owning “carbon copies” of their peer’s stuff and are rejecting bulk-produced items as a result, à la Phoebe Buffay from Friends and her vendetta against Pottery Barn.

Solomon also believes that her fanbase likes her videos because they love seeing into other peoples’ worlds.

“I think people like peering into that little window – they have that ‘who are they… how do other people live?’ type of curiosity,” Solomon says.

Comments on her videos confirm this. For example, one on a clip about a Pasadena sale reads:

She also thinks people see her videos as a way to connect with their pasts virtually.

Ogata has her mixing bowls, just as Fink has a vintage slips collection that reminds her of things she’s seen her mom wear in old photos. I hunt for film cameras like the ones my grandfather passed on to me. I own too many for someone who can barely afford to develop her film, but I like the idea of passing them on to my future children.

I recall watching my mother clean out her mother’s home.

“She never got rid of anything; there was so much in there,” my mom, Louise Corish, told me. Her mother, Sarah Fagan, died of cancer in 2011. “Everything was organized, but it was never-ending; I won’t do that to you,” she added. I remember watching my mom and aunt start sorting through her attic even when she was still alive, preparing slowly.

“I saved your schoolwork: writing, painting even, something that had some sort of meaning,” my mom said, reflecting on the work she did organizing for me, “I have a box of your little-kid clothes. That’s sort of enough. Everything I’ve saved for you can fit in the back of the car so that it can go to your attic.”

I appreciate her saving me the impossible editorial work down the line because if we love the person, instrumental materialism kicks in. My mom affirmed this, describing her relationship with Fagan’s wedding china.

“It’s hard for me to get rid of the sentimental stuff,” she told me. “My mother’s china isn’t anything I would’ve picked up, but what do you do with it?”

It’s a rhetorical question.

A clearer ask would be, “can I get rid of this without getting rid of them?” Our attachments to objects that belonged to loved ones speak to our shared connection. It’s why people like Hutchinson and Eleni are critical; they give a parting gift of one last relationship. A bridge for detached objects into new lives, looking for the next path. We are more than our belongings; but our spirit lives in each one.

I’m at my last Hutchinson sale, for the time being, a cramped one-story home in the La Crescenta foothills. I watch Hutchinson sort through the umpteenth box of old clothes, smiling as she works. She gestures to her band of helpers, some family members, and some friends. “When my time comes, they’ve got my stuff,” she added. Then, pointing at a photograph of the homeowner, she says, “I’ve got hers.”