By Enzo Luna

Skateboarding is a rebellion.

In the 1950s, when the first skateboard was created, the rebellion was against nature. Surfers in California solved the issue of bad surf by riding waves of concrete instead of water. But, even though skateboarding began as something that was surf inspired, it quickly transformed into something much bigger with skaters pioneering their way into the world of street skating.

Skateboarding remained a rebellion, but not against the concrete. It became a rebellion against the law. Los Angeles is an iconic skateboarding city, with many famous spots, such as the Hollywood High School Stairs, the ledges in front of the University of Southern California, and many more, but the caveat is that skating isn’t allowed in any of those places.

Skateboarding is unique in the sense that it is the only Olympic sport that is criminalized. Skateboarding where it is prohibited can lead to fines or even a misdemeanor on your record, which makes the sport a war with battles between yourself and with law enforcement.

Regardless of the different elements that have attempted to stifle skateboarding, it has flourished into one of the most diverse and fastest growing sports in the world. Community is the glue that has held it together.

Skateboarding and Race

A security guard places a barrier in front of a set of stairs in downtown Los Angeles. There are skaters on the prowl and the security guards are ready to face them. Even with a barrier and security guards threatening to call the police, the skater lands the trick, celebrates with his crew and vanishes with the quiet roar of the skateboard against concrete.

The truth is I am not describing a specific scenario. I made it up, but if you search “DTLA Triple Set” on YouTube, you will see exactly what I described played out in a variety of ways by many different skaters.

These sorts of interactions are a staple in skate videos. It represents the rebellious nature of skateboarding, but most importantly it represents the conquering of a challenge between a skater and themselves in the face of opposition.

These moments are universal to all skaters, but that doesn’t mean that each experience will be the same for every skater, especially if you are Black or brown. Rashad Murray, a Black professional skater, told Jenkem Magazine about how his experience is different from that of other skaters.

“I’ve noticed that the cops are way more respectful and polite to the white skaters I was with,” Murray told Jenkem Magazine. “I think when the cops see a white face it makes them feel more comfortable. But when they see me, they feel the need to ask questions and antagonize me.”

Things like this occur because skateboarding isn’t insulated from the issues of the real world, something which Dr. Neftalie Williams knows really well.

Williams is a sociologist and a USC Provost’s Postdoctoral Scholar at the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism, where he teaches a class on skateboarding. He is involved in the USC Skate Studies, which was made with the goal of expanding “notions of who skaters are and how they navigate their day-to-day lives” and has written extensively about the dynamics of race in skateboarding.

Williams initiated this conversation through his own work, there was some backlash. In his thesis “Colour in the lines: The racial politics and possibilities of US skateboarding culture,” Dr. Williams said that some within the industry argued that racism didn’t exist or that highlighting these issues within the community would “be unhelpful for developing greater social cohesion in the skateboarding community.”

Dr. Williams did not let this deter him both in his own work and in the USC Skate Studies.

For one part of the study, Williams and the team decided to focus on race in skateboarding in order to make it clear that we are not living in a post racial time, something which he said many people became more aware of after the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd by Minnesota police.

“We are all together and have a shared experience in skateboarding, but we don’t come from the same places,” Dr. Williams said. “What’s miraculous is that we’re creating a shared experience for one another, and learning from that experience, but that doesn’t change the worlds and environments that we live in when we leave the skatepark and so what we saw was that gender mattered and race mattered.“

What Dr. Williams was explaining isn’t necessarily that skateboarding itself is discriminatory, but rather that skateboarding exists alongside a world where racism and sexism is still a determining factor in shaping how people experience life. It is important to understand this, especially in the wake of so many injustices that Black and brown people have experienced at the hands of police officers.

So how do both Black and brown skaters, as well as women who skate, shred through a world that creates so many challenges for them?

The answer may be simpler than you think: community and a lot of commitment.

1. Community: Rashadi Stephens

Rashadi Stephens, a 22-year-old Belizean American skater began his journey on the four wheels only two years ago, but in that short time he has learned so much about the community and himself.

“I always wanted to skate, I just didn’t think I could,” Stephens said. “What got me to actually skate was just watching my friends, people that I knew could skate, it kind of inspired me and I was kind of going through a rough patch at that time so it kind of made me want to get better and it did.”

Stephens, who grew up in South Los Angeles, frequents his local skatepark at the Rancho Cienega Recreation Center. He said the park feels like home, but if he were to go to another park things would feel different.

That’s because the park he frequents is predominantly visited by Black and brown skaters, which is reflective of the community he lives in. Other skateparks though, are not reflective of his community and are predominantly white, an environment he is not used to.

“When it comes to the race thing and skateboarding it is very evident, but it’s also looked over,” Stephens said. “A lot of people don’t really see it because they mainly see diversity, they don’t really see the hardships that people go through, especially me being a black person certain things is like people look at you a certain way.”

Stephens said he hasn’t experienced racism in skateboarding firsthand, but he has seen it happen to other skaters in the form of microaggressions. For example, in an interview for Jenkem Magazine, Rashad Murray said that he has been told by other skaters that he “jumps higher because he’s Black,” and that his “heelflips are good because black skaters are better at heelflips than kickflips.”

These sorts of microaggressions don’t just come from other skaters, those outside of the community are also part of the issue. Stephens said that he has been told that he is doing “white boy shit” when others in his community have seen him skating.

Despite these challenges, Stephens has continued skating and like he said before, part of that can be attributed to him skating with his friends. The other part can be attributed to his own willingness to stick with the board.

“Skateboarding is built on muscle memory and really putting in the work,” Stephens said. “If you’re consistent and you really keep at it then you’re going to be good at it.”

This consistency and commitment to stick with skateboarding is what most skaters will tell you about how they became good at the activity. For some getting to that point, especially as a beginner, can be challenging and not because of a lack of self motivation.

Skateboarding is a culture that is predominantly created for men by men. In recent years we have seen more women make their way into the professional side of the sport, with some notable figures being Briana King, Momiji Nishiya, and Rayssa Leal, but the playing field still isn’t equal.

Skaters of color and women already face unique challenges because of their race and sex. The issue becomes more complex when you are both a woman and a person of color.

2. Community: Kyra Horton

Kyra Horton, a Black Chicago native and student at USC, encountered some challenges when she first started out with her journey as a skater.

“I feel like that whole period between 2017 when I was like longboarding to me trying to trick skate, it was so many obstacles,” Horton said. “It felt like a whole culture that I wasn’t meant to be a part of.”

Horton, who lived in Phoenix for a time did not begin skating beforehand because she did not see many people who look like her within the sport. Once again, like Stephens, Horton had been told that skateboarding was an activity for white people.

When she moved back to Chicago, she said she had a wake up call.

“This is not something exclusive to this specific identity,” Horton said. “Black people and just a lot of different non traditional identities are really like creating a whole culture, a whole movement, a whole community around skateboarding that I didn’t know anything about.”

Horton began skating when she was introduced to a Black and brown skate collective in Chicago.

“This is not something exclusive to this specific identity, black people and just a lot of different non-traditional identities are really like creating a whole culture, a whole movement, a whole community around skateboarding that I didn’t know anything about,” Horton said. “When I got back, that’s what really shifted all my preconceived notions about skating and what skating with skaters should look like and that’s when I started getting really involved.”

Horton said that being around people who looked like her and who were trying to learn about skating fostered her desire to better herself as a skater and to have fun. When she moved to Los Angeles for college, she brought that spirit here and started her own loose collective that was primarily for people of color.

What makes those sorts of spaces sacred, not just in skateboarding, is the lack of judgment and the abundance of acceptance. As you learn more, you come to find out why these spaces are necessary.

“I feel like as women and just obviously people in general, I feel like if we want to show interest in something, or we want to rep something that we like we have to prove that we’re experts,” Horton said. “…Men always are trying to get women to prove that they have a genuine interest in this thing or prove that they’re worthy of repping or being a part of the same because that stems from not feeling like women’s role or place in that court is legit.”

Horton has stuck with skateboarding despite these challenges and said it is an integral part of her life. The lessons she has learned on the board transcend it completely.

“Skateboarding has really created this confidence, that excels into every single aspect of my life, and also this extreme importance of community” Horton said.

Maggie Bowen, a USC student majoring in narrative studies, also experienced this boost in confidence as a skater, but with Bowen we begin to see how the intersections of identity matter, specifically the way in which race and gender shape how you experience skateboarding.

3. Community: Maggie Bowen

Maggie Bowen faced faced as a beginner skateboarder because of her identity as a woman.

“To be a beginner and to be imperfect, I think a lot of times to prove your authenticity, you have to be good,” Bowen said. “So to prove your authenticity you have to be a good skater and if you make a mistake, especially if you’re alone, and a girl, people look at you weird and they try to give you unwarranted advice, they try to hit on you, there’s a lot of different reasons why it’s really uncomfortable.”

This experience is similar to what Horton was talking about when she also started skateboarding, but what separates their experiences is Bowen’s whiteness.

“Being a white female in skateboarding, I think I’m the least likely to get in trouble if we’re going to go to a spot and we’re worried about getting kicked out, I’m probably the last person they’re going to take a fight with, which is definitely a privilege,” Bowen said. “But then at the same time, I still do get kicked out and still do get yelled at and still have that experience as a skater, but I definitely know it wouldn’t be the same if I looked different.”

Bowen points out something interesting. Dr. Williams said skateboarding provides a shared experience across identities, which is exemplified by the fact that Bowen, like many other skaters, will be kicked out of a spot either by security or police regardless of her gender and race. The difference though, is how those entities behave towards specific skaters. Bowen’s whiteness certainly changes that dynamic, but as a skater she is still part of a subculture that is actively being pushed against by the law.

Similar to Horton, Bowen found her place in skateboarding through collectives of people who looked like her. She is the founder of AuntSkatie, a skate collective for women, LGBTQ+ and nonbinary people.

(Photo by Enzo Luna)

“We meet up every week and usually I try to really focus in on the people who haven’t come before or the people that don’t come as regularly like the people that are kind of on the fringes, not sure about things,” Bowen said. “I’m going to try really hard to teach everyone something new so that when they leave, they know they learned something, or they’ve practice upon old skills, or they’ve expanded in some way.”

Not only does the collective help skaters progress in their journey, it also helps those who are part of the group a welcoming and safe environment.

“Usually, when you pull up in a posse of girls and there’s a lot of them nobody messes with you like that,” Bowen said. “Or if they try to, you can pretty quickly suddenly shut them down because you’ve got your friends there.”

Skateboarding, like Horton, has taught Bowen how to be confident and how to get up after a fall, literally and figuratively. Failure is inherent to it and a lot of it happens before you excel in it but what separates it from other sports is that everyone at every level continues to fall off their board regardless of skill level because of a spirit to keep expanding its boundaries.

Everyone Can Skate

There is no perfect skater.

Skateboarding has provided a community for Stephens, Bowen and Horton and it has instilled confidence within them as well as resilience.

Skateboarding teaches a valuable lesson about the ways in which community can help combat racism and sexism by connecting people to a shared activity. Skateboarding is not perfect and it is certainly not immune to the ills of the world, which is why Black and brown skaters, as well as women of all races, seek communities of skaters that look like them and share the same values.

Although skateboarding stratifies itself in these ways, these communities are connected. There are many instances where skaters of all backgrounds have come together to make some of the best skate videos, skate companies and skate competitions.

Skateboarding is a way of life, not just an activity, or a sport. It is a culture that is far reaching into the arts and which influences the very way that skaters view the world. A set of stairs isn’t just stairs to a skater, it is an obstacle.

Skateboarding is a rebellion and like all rebellions it is one that is based on love, community, and the desire to be free.

Just a Skater

Skateboarding is one of the most diverse and popular sports in the world, but it is not insulated from the issues of the world and it is often misunderstood. Mikem Nahmir and Don Cooley talk about their experiences as Black skaters and the important lessons that skateboarding has taught them along the way.

Self-expression

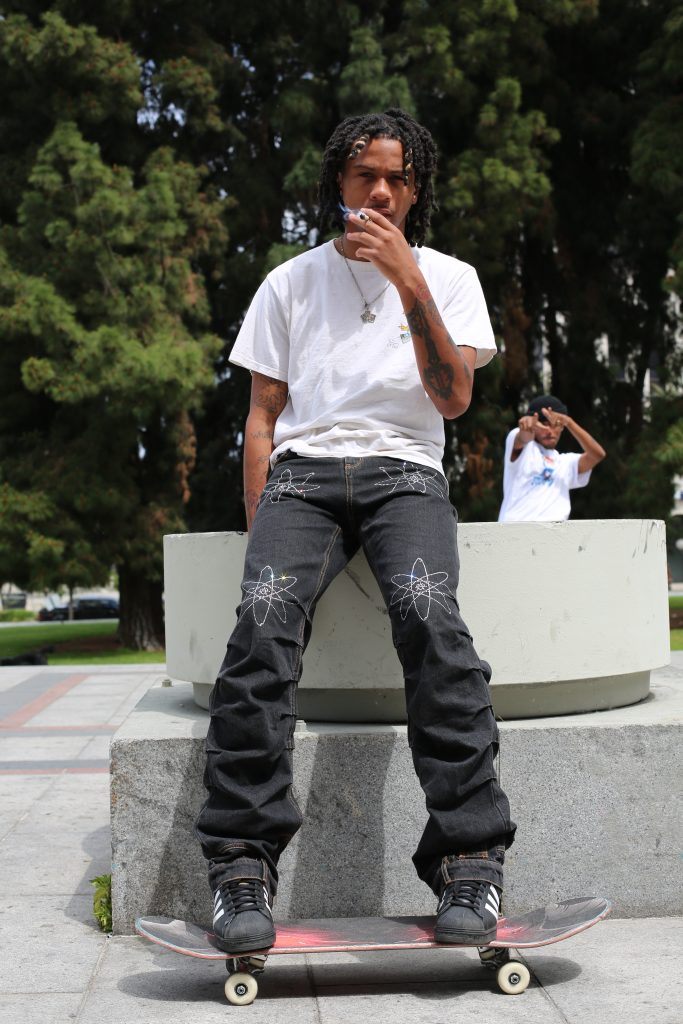

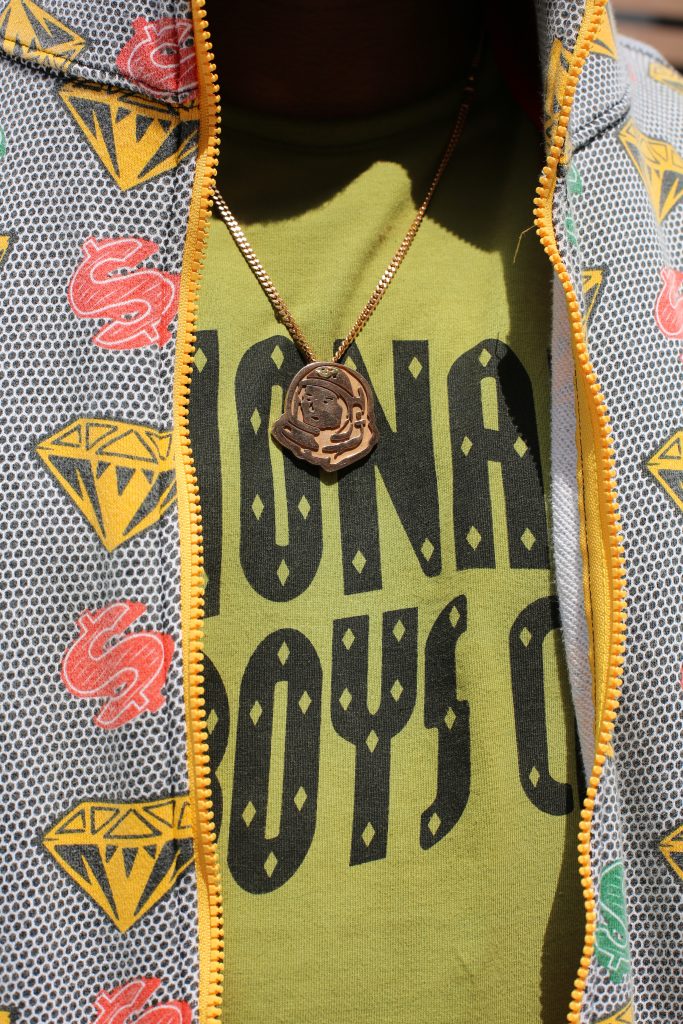

Skateboarding and fashion have been married for a long time now and their relationship has evolved over time. Although certain style trends have emerged throughout time in the skate world, such as Jordan 1s in the 80s, baggy pants in the 90s, and bulbous skate shoes in the early 2000s, there is no fashion requirement that skaters must meet. Self-expression in skateboarding is unlimited and everyone can skate in whatever attire they want. The following photo series, completely photographed by me, exemplifies the diversity of style found within skateboarding.

Briana King

Javan

Stan Three

Alex Martinez

Eric Valladares

Atzincli, Patricio and Ari Luka Farfan