A deaf elderly woman opened the door to her mobile home in the fall of 2018 to find search and rescuers quickly urging her to leave. She hadn’t known her neighborhood was being evacuated in response to the Woolsey Fire, nor had she heard rescuers banging on her door. Malibu Search and Rescue volunteers had noticed her trailer still had the lights on and eventually managed to get her attention.

“They evacuated her, and 10 minutes later her home burned down,” rescuer David Katz recounted.

Search and Rescue is a public service designed to keep people safe in the outdoors through utilizing the wilderness and medical skills of trained rescuers. SAR volunteers respond to everything from lost hikers, runners and climbers to cars that have driven over the side of the Pacific Coast Highway. Such rescues are free to the public and done by experts who volunteer their time to SAR.

Katz, the team leader for Malibu SAR, explained that many rescue teams use the phrase no charge for rescue. “The belief is that if we charge for rescues, people won’t call, and then they’ll get themselves in a more dangerous predicament,” he explained.

The Malibu team, based out of the Lost Hills Sheriff Station in Calabasas, California is perhaps the most well-known SAR team in the Los Angeles area as they were first on-scene to the helicopter crash that killed Kobe Bryant in early 2020.

Malibu Search and Rescue was founded in 1977 and is operated by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. This crew provides rescues throughout areas of the Santa Monica Mountains, the Santa Susana Mountains, and the contract cities of Westlake Village, Agoura Hills, Malibu, Calabasas and Hidden Hills. On occasion, the crew will offer assistance to other SAR teams across the state of California in places such as Joshua Tree or the Eastern Sierra.

Of the more than 30 volunteers for the Malibu team, most have full-time jobs outside of SAR ranging from school teachers to film directors. As part of their commitment to public safety in the outdoors, these volunteers often drop everything, including time with their families, to embark on a rescue.

Katz, Malibu’s team leader, has been a part of SAR since 1990 and has been on countless rescues. Katz began work in SAR after watching a newscaster describe an outdoor rescue scenario during which Katz felt helpless sitting at home. “I just want to be there doing something about it,” he explained.

Since Katz began rescuing in the 1990s, there has been a swift uptick in the number of people getting outside to adventure and, subsequently, getting themselves stuck in situations requiring a rescue.

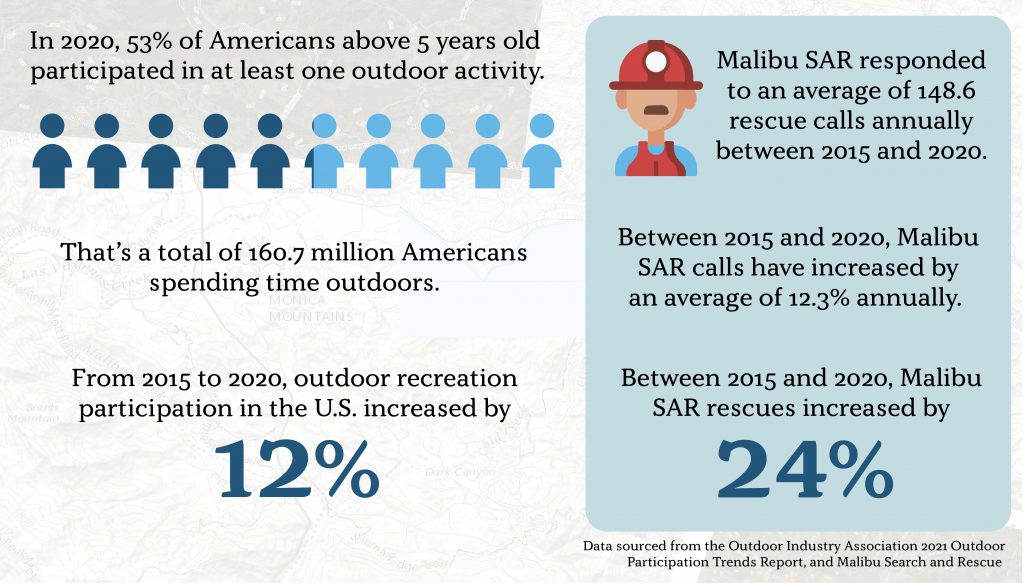

According to a 2021 study published by the Outdoor Industry Association, COVID-19 lockdowns and quarantines encouraged more Americans to venture into nature than ever on record. In 2020, 53 percent of Americans ages 6 and over participated in outdoor recreation at least once, an increase of 7 million people compared to the previous year. This jump was just a piece of a greater trend in outdoor recreation among Americans that has been increasing since 2008 and is projected to continue to do so.

The amount of rescues made by Malibu SAR has been trending upward over the last few years, explained Katz, who hypothesizes that social media is a driving force “for more folks to get outdoors and get themselves in trouble.” Given the trends indicating more Americans will continue to spend time outside and on trails, increasing awareness of safe practices is of growing importance.

The Malibu SAR team is made up of nearly 40 diverse volunteers who reside in various locations across the team’s jurisdiction and give varying amounts of time to rescues outside of their everyday lives and full-time jobs. Rescuers are expected to put in a minimum of 20 hours weekly, but everything remains on a volunteer basis, explained Katz, meaning there is no financial compensation for volunteers. Furthermore, the sporadic nature of SAR effectively requires volunteers to be on-call at all times, outside of their full-time work elsewhere.

“We don’t take off for holidays. We don’t take off for anything,” Katz said, referring to the rigorous commitment many volunteers make to their SAR positions.

Katz recalled one of many Thanksgiving rescue calls he’s responded to from a few years back that started out as a woman searching for her missing dog in Malibu and quickly became a rescue when the woman went missing alongside her pet. The team found her at the bottom of a well. After setting up a raising system, she was safely rescued, but Katz denotes this as one of the “craziest” holiday calls to date.

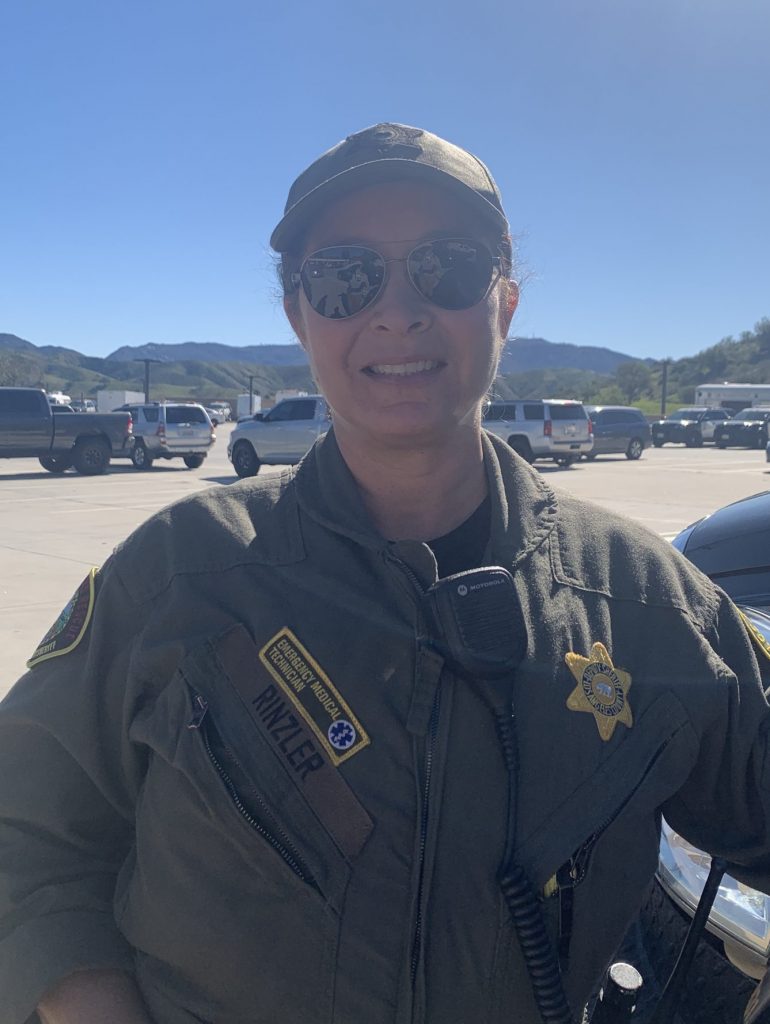

Karen Rinzler is a deputy sheriff who divides her time between search and rescue, working as a peace officer at the Twin Towers Jail Visitor Center and up until recently, teaching for a local preschool. She uses her afternoon, evening and weekend availability to be on-call for rescue missions.

After the birth of her two children, Rinzler knew she wanted to pursue something active in the outdoors. As a longtime outdoorswoman with interests ranging from day hiking to canyoneering, Rinzler explained that search and rescue is both a challenging responsibility and a hobby. “I love the outdoors, I love what we do on the team and I love training, learning new things. Being on a search and rescue team is really a lifelong learning opportunity,” she said.

Rinzler carefully explained that volunteer search and rescue is worth the inconvenient calls and hard work without the prospect of fiscal compensation because it isn’t a traditional full time job. Rescuers are not financially reliant on SAR and are thus able to make it into a passion project. Sometimes life as a full time employee becomes boring, Rinzler said, and SAR offers a valuable dose of adventure.

When it does feel tough, however, “it really becomes about supporting your teammates,” Rinzler explained. “Sometimes it’s two o’clock in the morning and I don’t really feel like jumping out of bed, but I know that there may only be two other [teammates responding] and it’s not going to be enough. I’m gonna get up and go support them.”

Oliver Hanely, a student at the University of Southern California, recently witnessed this type of support in action during a rescue in Ventura County, California. Hanely is a guide for SC Outfitters, a student-run outdoor guiding organization at USC, who was leading a group of students on a hike near Ojai when they came across another group of hikers, one of which had fallen and broken her ankle.

Outside of cellular service, none of the hikers with the injured woman knew how to handle the situation. Hanely and his co-guide – both certified Wilderness First Responders – stepped in as it quickly became clear the woman was not able to hike back to the trailhead. Aaron Bergen, a student participant on Hanely’s trip, used his GPS device to call for help.

The SOS button on Bergen’s Garmin InReach put him in communication with a first responder. After Bergen described the situation, the first responder dispatched two rescue helicopters to their location. Three rescuers stabilized the woman and hauled her into one of the helicopters for evacuation.

Although this rescue was not completed by the Malibu SAR team and rather another in the area, the response was efficient and safe. Bergen marveled at the quick response time and resources provided. “It was really surprising. I’m glad that it wasn’t me, but if it was, I’m glad to know I would be taken care of.”

Hanley takes new adventurers into the outdoors frequently, but after this experience, mentioned that “it’s pretty shocking how little some people know what to do in those situations. If we weren’t there, I don’t know what [the injured hiker] would have done,” he added.

There is rigorous training involved in becoming a member of a rescue team to prepare volunteers for situations like Hanely’s. Although different SAR organizations require varying qualifications, most of the Malibu volunteers are also reserve deputy sheriffs. The process of becoming a reserve deputy sheriff takes between two and three years; search and rescue training takes between four and five. In other words, volunteers undergo years of training and learning to become certified rescuers.

Volunteers work in a variety of landscapes ranging from cliff areas and steep hills to deep bodies of water. To be prepared for diverse rescue scenarios, rescuers must become privy to an array of gear and rescue techniques. Volunteers are typically seen in their signature green jumpsuits and have an array of gear with them such as helmets with headlights and field-safety medical kits that can be attached to their suit.

One of the largest pieces of gear rescuers use is a litter, which functions as a basket to carry injured patients out of the field. Patients are secured with various straps to stabilize their position and a cover folds over the patient’s head to protect them from any falling debris.

All the gear necessary can’t feasibly be carried in a backpack or go-bag, thus Malibu SAR has rescue vehicles that respond to calls. The heavily outfitted trucks act as a homebase in the field and house nearly all the gear needed for any rescue mission they are faced with. In the following video, Katz provides a walk-through of one of the rescue trucks with all of its bells and whistles.

Volunteer James Grasso just recently finished his training and is one of the few non-sheriff rescuers on the Malibu team. A so-called “day job” as an assistant director in television and film still affords Grasso enough time to pursue SAR, which has quickly become a top priority. When deciding to join nearly five years ago, Grasso wanted to do something that was action-oriented and hands-on. He has found that SAR fits these desires and has committed a large chunk of his personal time to the team, sometimes putting in more than 100 hours monthly.

“I oftentimes look at [SAR] like it’s selfish. I do it because it feels good, because I like to help my fellow citizens. I like to make things better than they were before,” Grasso said.

There are only a few major distinctions between civilian volunteers and deputy sheriff volunteers according to Grasso, namely that civilian volunteers are never armed and are not sworn in. “In certain situations, we have to act differently or not act at all,” Grasso said. “But for the vast bulk of what we do, it doesn’t really seem to make a significant difference.” These distinctions, however, require a longer training period for reserve deputy sheriff volunteers.

Grasso prides himself on how quickly he is able to mobilize for a call. He keeps his jumpsuit hanging by the door and claims it typically takes him about five minutes to get prepared and on his motorcycle in response to a rescue, given he is not at work.

Volunteers have honed in on the speed of this process because they can get calls at any time. Of the nearly 40 volunteers, not everyone is available to respond to every call. Those that can respond do so with efficiency, dropping whatever else they may be doing to get to the scene. “You’re thinking, ‘jeez, if I go out to dinner tonight, can I have some wine? Because if I have wine I can’t go to the call,’” Katz mentioned.

Upon asking rescuers what mistakes most commonly lead to rescue dispatches, Rinzler, Katz and Grasso agreed that there are a few simple errors that could prevent a large portion of rescues in their area.

First and foremost, Southern California is often hot and very dry with many exposed trails, and adventurers don’t always properly account for how much water they need to bring with them. Bringing more water than you think is necessary is never a bad idea, according to rescuers. It’s also important to know where you’re going, they agreed, and have accessible directions in the event that your phone dies so you can at least make it back to your vehicle.

Rinzler recommends utilizing a GPS service on your phone such as Gaia to stay found on trail. “People bring their phones everywhere. If they have a GPS app turned on, they will never get lost again,” she suggested.

There is a generic list of ten hiking and camping essentials widely agreed upon within the outdoors community that when accounted for, can make the difference between an adventure that ends safely and one that doesn’t. This list includes: navigation, light source, sun protection, first aid, knife, fire, shelter, extra food, extra water and extra layers. Although many outdoor exploits may not require each of these items, it is generally recommended to be over-prepared rather than under-prepared as weather, trail conditions and injuries can quickly change the pace of the day.

By taking steps to keep themselves safe, hikers, climbers, bikers and other adventurers in Southern California and elsewhere can often avoid meeting rescuers in the field. As more folks get outside, it is their responsibility to recreate safely, but just in case things do take a turn for the worse, rescue volunteers are just a call away.