More and more Californians have reported seeing colorful avians soaring over their homes, even in the city. Especially in the city. It poses the question: where did they come from, why are they here, and are they here to stay?

By Mia Ross

When the pandemic sent everyone home from my college and we were ordered to stay inside to help stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus, I happily obliged.

I arrived home in Buena Park with a little too much excitement, given the dire state of the world at the time. But my excitement wasn’t about staying inside or taking a break from extracurriculars. I was thrilled to return home and spend time with my sweet ray of sunshine, the apple of my eye: Buster, our family bird.

Anyone who knows me can attest to my undying love for birds. Any size, any shape, any color, any bird—they’re all sweet little angels, every last one, and I’d adopt hundreds if I had the means. I’ll talk to any bird I see while I’m walking out in the city, earning myself numerous concerned looks from passersby. Buster is the most important bird in my life, though. I talk about him endlessly to my friends and family, and I’m happy to say that everyone I know can now rattle off my bird’s name, species, age, and range of vocabulary on demand.

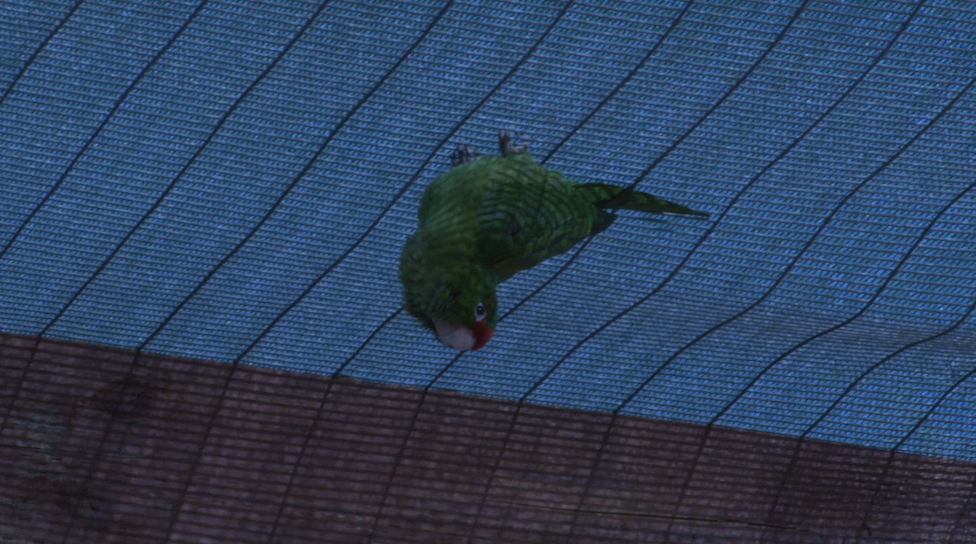

He’s a green-cheeked conure—known scientifically as Pyrrhura molinae, colloquially as a clown—and we celebrated his twelfth “hatch day” on May 3, 2022. His favorite phrases include “pretty baby,” “Buster bird,” and “love you, love you,” but he’ll never turn down the opportunity to tell one of us to “shut it!”

I love Buster the same way a dog lover loves their dog: he is my baby, my best friend, and I would do absolutely anything for him without hesitation, no questions asked. He’s been in my life for eleven years now, and I know him like a parent knows their child. I know when he’s hungry, I know when he wants to take a bath, and I know when he’s scheming to fly to the top of our cabinets, hide, and shred the particleboard like confetti. He’s a loud, sassy little troublemaker, and I adore him for it.

On my first morning back at home, I was awoken shortly after sunrise by a contact call: the ear-piercing shriek birds make to alert their flock that they’re there, even if they cannot see each other. Except, this wasn’t Buster’s signature gravelly, scraping contact call I knew so well. This was much more shrill and came in short bursts, followed by more short bursts. I’d heard this maybe once or twice before around my Los Angeles apartment, but certainly not from my tiny conure. And so, I got out of bed to investigate.

I opened my bedroom window to a flock of large, green-and-red parrots, dive-bombing with each other through the trees that towered above my window. Some were cuddling atop the powerlines, preening each other amidst the ear-splitting sound of 20 parrots contact calling each other, over and over again.

I couldn’t believe my eyes—or my ears. I’d loved parrots all my life, but I had never seen one in suburban southern California. Like others, I mistakenly thought that parrots equaled tropical, so I never expected to see one in the wild unless I traveled to their natural habitats in South America. As a bird lover with nearly nothing to do during a global pandemic, it became a passion project of mine to investigate these brightly colored, deafening fliers. Why had they become ubiquitous outside my window in Orange County and even on Greek Row?

Who are these urban birds?

“I always tell people, I think if they had thumbs, they would totally take over the world,” joked Sarah Mansfield, the operations manager at SoCal Parrot Rescue in Jamul. “They have the emotional intelligence of a toddler, but they also have the physical capabilities of a toddler with a tool kit: just, ‘destroy.’”

Mansfield, an employee of SoCal Parrot Rescue in San Diego County for almost nine years now, has a soft spot for the parrots at the rescue. She left her job at a tech startup in 2016 to be with the birds full-time, despite the relentless noise they produce, because of their animated personalities and her love for animals.

“They’re a lot more intelligent and capable than we give them credit for,” Mansfield explained. “They like to play. They’ll hang upside down sometimes in trees and they’re not even eating the flowers. They’re just pulling them off, or they’ll take one bite of something and drop the rest. Also, when it’s raining, even here at the sanctuary, or if I’m giving them a shower with the hose, they’re playing in it, they’re hanging upside down. They’re flipping over, they’re dancing, they’re singing. They’re just really fun.”

Most of the parrots we see in southern California are of the genus Amazona, including red-, yellow-, and lilac-crowned Amazons. The red-crowns are the birds I saw outside my window on that remarkable day in March 2020, playing with each other in ignorant bliss of the sleeping humans below them.

Native to northeastern Mexico, red-crowned Amazons are the most numerous non-native parrots in southern California as of the past decade or so. Their exact numbers haven’t been surveyed since the early 2000s—counting identical flying animals is a complicated task—but experts suggest that there might be anywhere between 2000 and 4000 Amazons roosting in California today, not to mention the thousands of others residing in parts of Florida and south Texas with similar warm, dry climates.

These feathered friends of mine are a naturalized species, meaning they are not native to this region but have integrated into the ecosystem and established self-sustaining populations here. Kimball Garrett, the ornithology collections manager at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County since 1982, is responsible for a substantial portion of research and data collected on avifauna in Los Angeles, including the study of the 13 naturalized parrot species now residing in California.

I was lucky enough to sit down with this fellow lifelong bird lover two weeks before his retirement to talk about the world of aviculture with a special focus on the parrots of Los Angeles. The result of our nearly two-hour interview—supplemented by researchers at Occidental College’s Moore Lab of Zoology—paints a full picture of the delights and sorrows concerning the playful psittacidae who have declared our state their home away from home.

How did parrots end up in California?

There are a number of theories about how these parrots got here in the first place, from the illegal bird trade to the effects of climate change forcing them to migrate north toward favorable conditions (parrots are not migratory birds though so that one’s out). While each theory may have some degree of credibility, Garrett says, the illegal pet trade ultimately underpins each of them.

“[There are] a million sort of urban legends about how parrots became established, and everybody has their favorite,” Garrett teased. “However, what we do know is they all stem from the pet trade. There’s no parrots that occurred here naturally. You will talk to people who will say, Oh, we had some big storms or hurricanes or whatever that blew them all up from Mexico or whatever. No, that didn’t happen. They’re all here because of humans transporting them from their native range here for the pet trade.”

The history of owning exotic pets dates back to antiquity: the Egyptians mummified millions of sacred ibises as sacrifices and were often buried alongside them, and the Romans kept colorful fish for decoration in their homes. Owning such animals as we know it today, though, traces back as early as the 1950s and 1960s when commercial air travel made it much easier to transport animals discreetly across international borders.

When exotic bird importers brought parrots across the California-Mexico border and suspected they might get caught, they would release their flocks of wild birds. And since California boasts a wide array of non-native tropical plants, these birds were almost right at home.

Why is Los Angeles, of all places, an ideal habitat for parrots?

“If you look around urban Los Angeles, the trees and shrubs that you see, virtually none of them are native to this immediate area,” Garrett explains. “For urban areas, the preference seems to be to import a lot of water, irrigate things, grow tropical and subtropical plants and things from all over the world, keep them watered, keep them thriving year-round so that we’ve got food produced for things like parrots, which eat primarily seeds and fruits year-round. They find the habitats that they need, and so they just thrive here.”

“They will show up for loquats and eucalyptus, but they really like all types of non-native fruiting and flowering trees,” Mansfield added. “If you want parrots in your yard, plant some loquats!”

The abundance of flowering and fruiting trees is only one element of survival that plays out in the parrots’ favor, though: many of the predators they face in their native regions of South America don’t live here. They also aren’t being poached for the illegal pet trade (which, despite its illegality, still happens today), so they can reproduce more safely and populate at a faster pace.

“There’s a much bigger arsenal of predators in tropical woodlands than there would be here,” Garrett said. “Yes, we have Cooper’s hawks and a few other things that might occasionally take parrots, but by and large, they don’t have a whole suite of different kinds of predators coming after them here. So in many ways, it’s kind of ideal for them.”

An additional advantage? Los Angeles is pretty much as urban as it’s going to get. There isn’t really any construction affecting areas abundant with wildlife; most of those areas are protected. The city has been industrialized for many years, and while biodiversity has certainly been lost, the existing animal life in the city is pretty stable.

Stability is one thing that the Amazons don’t have in their natural environment: regions of northeastern Mexico where these birds reside are undergoing devastating habitat loss from logging and deforestation, largely to convert land for agricultural use. Red-crowned parrots were moved from Threatened to Endangered on the IUCN’s Red List in 1994 due to their declining natural population, and the numbers haven’t been surveyed since. Experts can only speculate as to how much more that number has decreased in the last 28 years.

The state of the red-crowned parrot’s natural habitat

Luckily, the naturalized parrot populations don’t seem to pose a threat to existing avifauna in California. Each expert I spoke to said that while they occasionally interact with crows, the parrots have not contributed to any kind of species degradation within the ecosystems they have blended with. In brief, they are classified as non-invasive, and thus there is no reason to make an effort to get the parrots out of here (much to my own joy).

However, while they continue to thrive here, their native counterparts in Mexico have suffered for decades. Sean Lyon, the curatorial assistant at the Moore Lab of Zoology, emphasizes that the red-crowned parrot’s situation is ongoing and should not be taken lightly.

“The situation is incredibly dire. The pressures that they face are several: both habitat loss, direct persecution by humans, and invasive or non-native species entering their ranges that may act as nest predators,” Lyon emphasizes. “Where there used to be hundreds of thousands of individuals, now we only see hundreds of individuals total. I think that it becomes incredibly important to see this as the 11th hour of their total timeline of what can be done.”

As the parrots face up against poachers, deforestation and industrialization threatening their native range, the looming consequences of climate change are creeping up slowly but surely. Lyon notes that changes in rainfall patterns, in addition to the obvious changing temperature, places significant stress on the forests that these birds call home.

“The overall instability of these new patterns that we’re seeing or the lack of a pattern entirely just means that the forests are becoming, in some ways, less hospitable places for a lot of the species that are native to those ranges,” Lyon clarified.

Even the dwindling number of livable forests for these birds may not be able to sustain the species in the long-term. This is detrimental to an already-decreasing population. To put it bluntly: it is entirely possible, even likely, that the United States will be the last place in the world to see red-crowned parrots someday if the situation continues to deteriorate.

What happens if they become extinct in their natural habitat?

Fortunately, the species likely won’t go fully extinct, at least not as the situation stands: there are currently more red-crowned parrots in the United States than in their natural habitat, and the number of these naturalized birds is said by experts to be steadily increasing.

That being said, the extinction of these parrots in their native habitat would cause great harm to the species as a whole. Preserving the individuals native to an area means more than just saving the species: it maintains unique behavioral, genetic and even potentially dialectical diversity that does not exist in a population from a different region that has never interacted with the original population. Losing the native population of red-crowned parrots could permanently wipe out biosocial discrepancies that do not exist in their United States counterparts.

“[It] is a really important thing to take into account the parrots that are in their native range have evolved to exploit natural niches and to really flourish the most that those birds are going to in the long term,” Lyon explains. “[They’ll] be exhibiting somewhat different qualities than these birds that have been transported from that native range into these natural habitats. And we are still understanding what some of those qualities might be, whether there are certain genetic qualities or behavioral or social attributes to these birds. So in a sense, we don’t know all of the richness that we’re preserving when we are preserving a group of individuals in their native range. That is something that when it is lost, it cannot be reinstated, even if the population grows back to that same size.”

As Lyon previously emphasized, we are facing the last call to help save these silly, chatty avians from certain extinction in their native home. We are risking the loss of a vault of genetic, social and behavioral biodiversity that has yet to be studied. For a bird lover like myself, this is a harrowing realization I cannot help but try and challenge. What is there to be done for the red-crowned Amazons of Mexico?

How do we save the parrots?

The first step to making a difference in nearly any domain is raising awareness. Nobody is going to help birds they don’t know are in danger, let alone birds they know nothing about.

Obviously, working toward conservation means reducing our ecological footprint as human beings. Using less power and water in addition to calling upon our local and national government(s) to implement more sustainable practices is an ongoing struggle, though its importance cannot be overstated.

For people who are already parrot enthusiasts, self-educating on the situation in the birds’ South American natural habitat is essential. By opening ourselves up to knowledge of the circumstances abroad, we gain a greater appreciation not only for the positive effects these feathered friends have on our lives, but on the lives of those who are experiencing their loss.

“Often the most successful restoration and conservation projects are those that are done in close partnership with the local communities that live in the regions that are seeking to be conserved,” said Lyon. “[We can] seek to support organizations that are working on the ground in those areas.”

Despite the focus on red-crowned parrots in this story, a key aspect of conservation is to take a step back and look at the bigger picture. Lyon emphasizes focusing on preserving biodiversity as a whole rather than on a species-by-species basis to work towards saving an entire ecosystem that would otherwise cease to exist without the parrots, rather than looking at just the birds alone.

“The management of landscapes through a biodiversity-wide perspective rather than through a species-specific perspective often reaps much greater benefits in terms of the overall health of the ecosystem,” explained Lyon. “To set aside some land as a regional or national park rather than a park that is solely suited [for parrots] to fly, for example, means that there may be a lot of other species that can benefit from that conservation attention.”

Another solution—albeit ambitious and costly—is that of species reintroduction. The idea has been thrown around in many avicultural circles as a potential solution for declining species even before the status of red-crowned Amazons entered the conversation. However, it’s quite a demanding undertaking.

Marky Mutchler, a post-graduate research assistant working alongside Lyon at the Moore Lab of Zoology, detailed the theoretical process for me.

Let’s say the parrots go extinct in northeastern Mexico, while their populations in the United States either stabilize or continue to grow. Conservationists and government offices could put forth resources to rebuild and renew the habitat from whence the parrots came, theoretically back to a level that could support the species once again. Then, a number of genetically intact, disease-free parrots from their naturalized habitat in California would be transplanted into the region to begin repopulating their native region, taking all the experiential advantages of urban living with them.

“I have high hopes for it,” Mutchler beamed. “If you look at Los Angeles, it’s a huge city and the parrots so far seem to be doing well. Even though the parents in Mexico are declining and their habitat is declining, maybe there’s something allowing these parrots to continue to exist. So maybe drawing from these populations and reintroducing it can help those other populations coexist with the expansion of cities and habitat degradation.”

There are a fair number of pros. Urban parrots entering northeastern Mexico for the first time may be better equipped to handle threats, since they have experience living amongst stressors that their predecessors never faced. They adapted to Los Angeles smog and air pollution, so that has to count for something. Additionally, a lengthy undertaking like species reintroduction can really assemble groups of people united by a common goal, which certainly aids the process.

“To reintroduce a species means reintroducing part of the historical-cultural landscape of that place, and for many people who live in regions where there is an imperiled bird species, it kind of becomes a rallying cry for their region,” Lyon said. “It becomes something that people are proud of and kind of look to as an identity symbol.”

It sounds great: we get the chance to rejuvenate the environment, save the birds and let them return to their natural habitat without hurting the ones we have here. It is certainly possible. Unfortunately, many great ideas come with caveats, Mutchler indicated.

The process would take years and exorbitant amounts of money that most ornithological initiatives could only dream of. Transporting the birds safely and efficiently would introduce a significant financial barrier. It would require genetic testing of every potential transplant parrot to make sure they are genetically pure and not hybridized with other species of Amazons. Not to mention, someone would have to go out and catch all these birds.

Additionally, it would have to be absolutely certain that the region the birds are being reintroduced to could sustain the species long-term. Reintroducing a species to an area too early and causing a significant number of expensively-transported, genetically-tested birds—of an endangered species, no less—to die out prematurely would be a devastating hit to the conservation of the species.

Each of these solutions includes an abundance of nuance and debate over best practices, financial costs, and other factors that play into how things get done in the world we live in. As it stands, there is no immediately actionable answer to the question of conservation. Without mass support and the means to do so, it is highly unlikely any of these solutions would prosper if we pursued them starting right now. It all depends on the court of public opinion regarding the parrots and what gets addressed in the realm of climate change.

Okay, so what do we actually do?

Since climate change legislation and action seems to be moving at a snail’s pace in America, what’s the compromise? How do we meet in the middle on the brink of life-and-death for an entire species?

First of all: stop supporting the exotic pet trade. If you haven’t done it yet, good. Don’t start; adopt from local shelters, regardless of the animal you’re looking for. Adopting domesticated birds that have been surrendered to a shelter combats the trade of exotic birds that still happens today, despite legislation intending to ban it. Buying from a pet store increases the demand for pet parrots, which “justifies” unethically breeding them or taking them from their roosts as babies, continuing the cycle of poaching that is damaging their native species in the first place.

If you think a bird might be a great companion for you, do extensive research. Many parrots live for decades—Buster’s estimated lifespan is about 30 years with proper care—occasionally outliving their owners. Obviously, parrots are LOUD, so if you have a tiny apartment in Los Angeles, maybe get a cat instead. If you’re a busy workaholic, a parrot probably isn’t right for you: they need constant (and I mean constant) attention. There are about a million other dos and don’ts of parrot care, but I’ll stop myself.

Educate those around you about conservation and the naturalized bird species of California. There are 12 species of parrots in addition to the red-crowned Amazons that can be seen across southern California, and there are more than 100 naturalized bird species in total. If nobody knows about them, how can they possibly be protected?

“The public sentiment needs to shift to a place where we not only accept them as naturally occurring within the southern California area, but also that we want to protect them and keep them thriving here,” Mansfield suggested. “They may not exist anywhere else except in urban settings in southern California and maybe parts of Texas and Florida someday.”

Accepting the situation as it is—we have parrots in California that aren’t supposed to be here, but they are, and their presence may be saving them from total extinction—may be the most realistic course of action as of now. Taking care of the birds we see here in Los Angeles, educating ourselves and others on how to respectfully coexist with them, and appreciating their unconventional presence are just a few things we can all reasonably do to protect one of California’s naturalized parrot species.

Because honestly, bird lover or not, you’ve gotta admit it’s pretty cool to see parrots hovering over the I-5, screeching to one another as if they’re laughing at the fools perpetually stuck to the pavement.