BY ANNIE NGUYEN FOR JOUR 414

When you’ve lost something, you retrace your steps. Where have you been? Where did you go? Your keys, your uniform, your name, perhaps even your home. Look at the last place you remember it being. Maybe ask your mom.

Part One: A Gun

Mirroring many Asian linguistic traditions, in Vietnam, our family name is recited first. Women usually don’t change their surname after marriage, though her children are given their father’s family name. Someone as distant as a foreign nation or someone you’ve never met could figure out a common ancestor with this simple rule. My name therefore isn’t really mine at all; “Nguyen” is an entire history of people who made decisions that amounted to my being.

Not so far away but still a stranger, my great uncle’s brother in law Nguyen Ngoc Loan also shares the same surname as me, along with more than 40% of the Vietnamese population, and even his future executee Nguyen Van Lem.

Retrace the moment he shot that man in the head.

Where have you been? Well, if you’re Loan then you’ve realized the family of one of your deputy commanders was killed by the terrorist squad the man led. Before that, you were a pilot. Rewind further. You were trained in pharmacy practices. You grew up in Hue with your ten siblings. You were a boy.

Where did you go? To war.

You chose a career of violence while your younger sister marries a doctor, who will take them both to live in the United States. Now, she and her husband own a lovely home, the kind a doctor can afford. They adopt a dog. They invite family over for parties. Dr. Nguyen Thanh Thuy also shares your name. Coincidental but not uncommon. Of course, that means you also share a name with me.

“Communists kill us,” my grandma warns.

My grandmother is the eldest of seven. Her younger brother, though the third born, rose to the top of their chain. The kids called him Ông Tu. When I was little, Ông Tu would give me stickers after his general check-up appointments. His medical degree hung on the beige wall of the clinic’s office but more impressively, he had one of those toys in the lobby that was a wooden square with metal squiggly things poking out the top forming a bead maze. In a mundane SoCal plaza overexposed with beige and two floors, another patient could find us in a mini family reunion.

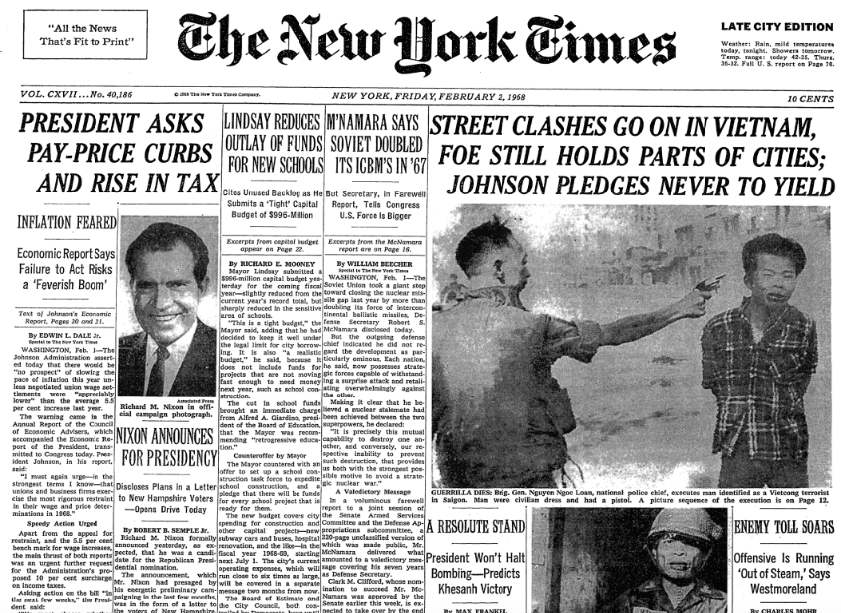

Ông Tu’s brother-in-law was once a boy and when war broke out, grew up quickly to become the national police chief of South Vietnam. On February 1st, 1968, a plains-clothed Viet Cong fighter stood at the end of the pistol that would cost Loan his life’s reputation and win the onlooker with a camera a Pulitzer prize.

Practically overnight, Nguyen became a name of blood on American tongues. Eddie Adams’ picture would be deemed one of the top one hundred most influential photographs, and rightfully so. After its publication, Americans’ opinion about the Vietnam War shifted to widespread disapproval. Who’s side were we on anyway? They spoke about being in Vietnam with self-disgust and urged their patriots to return home.

Yet, for generations prior, Nguyen was already a blood name. That blood poured during wartime, but it had run essentially through the veins and pumped through the hearts of millions already embodying the name.

Part Two: A Girl

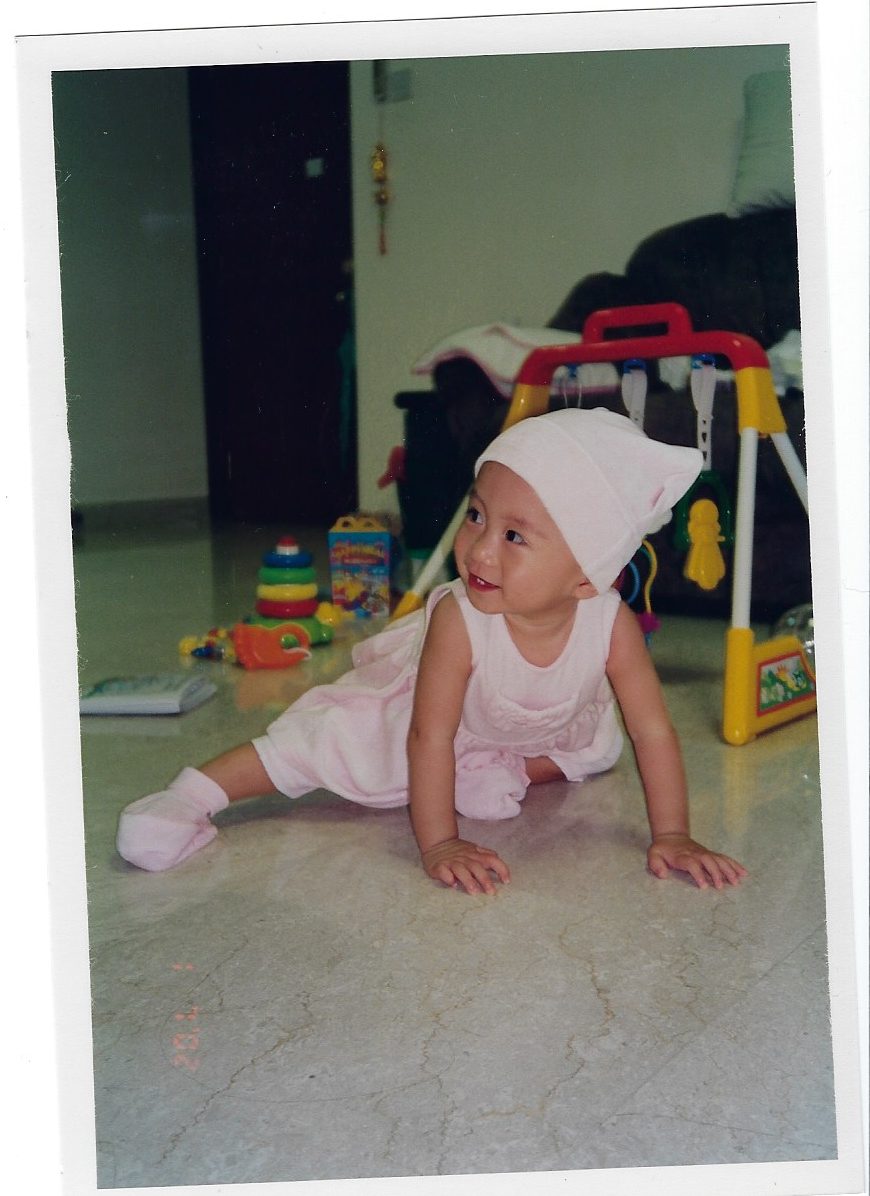

My name is a blood name. My mother immigrated to the US with me and my younger brother in 2004. We learned English by watching PBS and making friends with kids who could also barely read.

Does the Vietnamese American tongue speak of self disgust or of essential ancestry? That photograph of the execution is digitally plastered onto the screen in the auditorium where I sit in class. It’s my first couple weeks studying journalism at USC in Los Angeles and well, if I have something to say – I raise my hand.

“I’m related to him,” I announce to a lecture hall full of half-focused students.

“Who? Which one?” my professor asks.

“The man with the gun.”

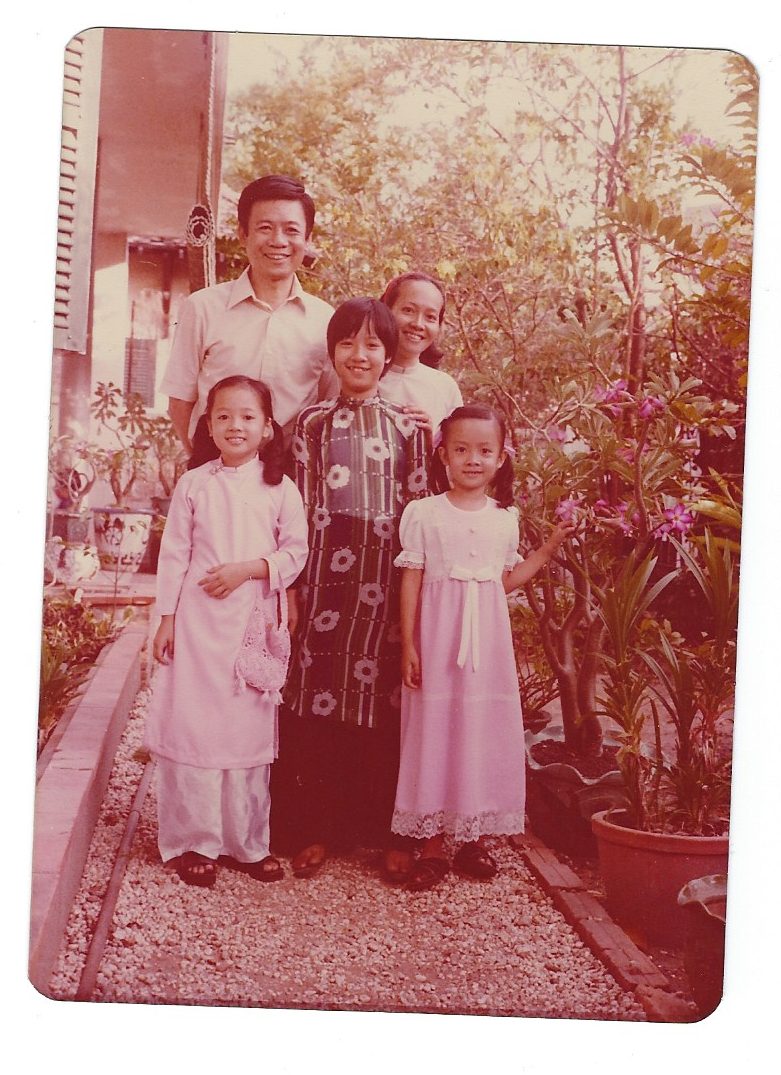

If I can’t relate to violence, am I still its relative? What I know about my family is because of my grandmother, my Ba Ngaoi. She was born in 1938 to Buy Thi Tien and Nguyen Van Lam, who owned the first popcorn maker machine in the whole country.

In 1968, while her short-tempered brother-in-law pulled the trigger, Nguyen Thi Hoang Hai was at the Tan Son Nhat airport working as a translator. That year also prompted the birth of her eldest daughter, who at fourteen years old, would got caught by government officials after trying to flee on a boat with another relative.

Forced to speak only French at Trường Trung học Phổ thông Marie Curie – a public high school in District 3 of Saigon established under French rule – Ba Ngoai become affluent in not only her mother tongue but also that of her colonizers.

It wasn’t all so terrible, though; the way childhood never really is. She had a natural gravity towards new languages. She never turns down a sweet treat from a patisserie. She hums the lyrics and melody of La Vie En Rose in kitchens while washing rice before dinner for decades after her school friends introduced her to the song. When Gone With the Wind (1939) continued to screen at cinemas in Saigon, she awed. It would become her all-time favorite film.

“All people go, at this time. American films – everyone go to have it. And the film actor, the actress is very wonderful, beautiful,” she recalls.

Oh, America the beautiful.

Eventually, she married my Ong Ngaoi, who had watched a friend die right next to him in a South Vietnamese Air Force helicopter. Once, he shot a lizard on the living room wall with a gun because my baby brother was scared of it.

When South Vietnam fell to the communist North in 1975, so did the option to continue work and school as was usual before. The family opened up a coffee shop to sustain themselves. Their shop wasn’t so much a storefront as it was run out of the house they rented on Truong Tan Buu. Each day, their home sold cups of coffee and chè – Vietnamese dessert cocktails that come in an infinite array of flavors. Whether it was chè Thái or chè ba màu, the specific type rotated daily. If not running pseudo cafe, days consisted of going to the market to buy green beans, coconut milks, and bánh bột lọc powder mix. Even captured, the voice of the stomach usually begs for peace.

Grandmothers always seem to speak by putting a meal in front of you. Yet, words have difficulty in timing. Despite sharing a name, we don’t share a language. Our conversation fragment like mosaics, the way the glass is always tinted. Grasping for proximity, our voices are muffled. Our name gets hard to pronounce.

On June 24th, 2001 – Adams wrote a eulogy for Loan in TIME magazine reflecting on the moment from four decades ago, “Two people died in that photograph […] The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera.” Two weeks later, I was born.

In the same TIME piece, Adams wrote “The photograph also doesn’t say that the general devoted much of his time trying to get hospitals built in Vietnam for war casualties. This picture really messed up his life. He never blamed me. He told me if I hadn’t taken the picture, someone else would have, but I’ve felt bad for him and his family for a long time.”

“Saigon Execution” has a well deserved place in history books, though I bet they’re mostly in English. Respectfully, it’s so tiring to watch people feel bad for our family. Our name isn’t a pity.

Part Three: A Camera

Much of the Vietnamese imagery in the American public’s media library is in relation to a war that America only made worse. In a cinema studies class, it was taboo that I refused to watch Apocalypse Now (1979). To claim it to be a masterpiece would mean in a story about Vietnam, if the filmmakers are geniuses, it is fine if the only Vietnamese people on screen are voiceless extras either dead or peasants meant to be decorations to American men draped in camouflage.

In fact, the story will even win eight Oscars at the 1980 Academy Awards.

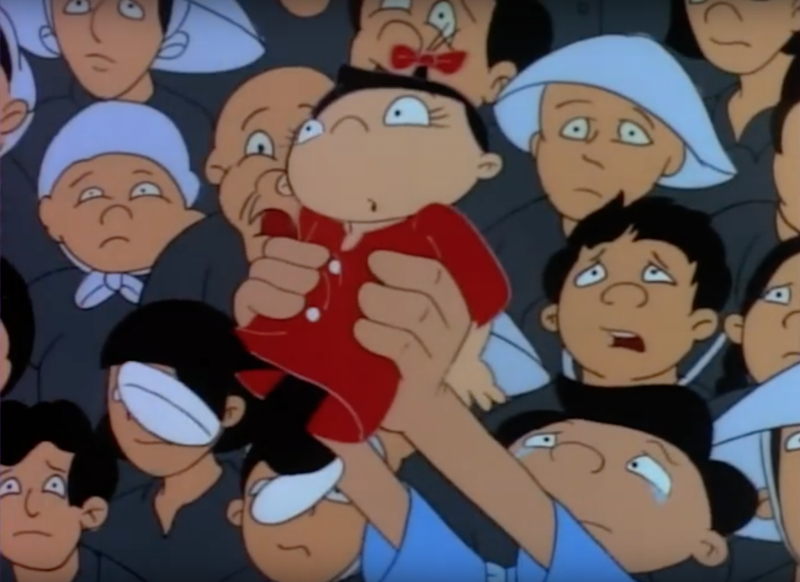

Even in stories that treat Vietnamese people as capable of feeling joys and agony, their name is also uttered approximate to the war. In the celebrated Hey Arnold! Christmas episode from its first season, we follow along the forced separation of a baby girl, Mai, from her father, Mr. Hyunh, a Vietnamese refugee who lived in the same boarding house as Arnold.

Under the American lens, Vietnam is full of jungle and gunfire. Saigon is a city fallen, never the city of cháo gà (rice porridge) or gỏi cuốn (spring rolls) and “Hondas”, the umbrella term for the mass of motorcycles that dominate roads.

But I’m holding the camera now.

Plus, I’m not the only one with a plan to retrace my steps. Young Vietnamese Americans like Dwight David Hua are growing up to come to terms with the systems that placed them where they are now. A current junior at Stanford University studying psychology with minors in ethnic studies and sociology, Hua leads the Stanford Vietnamese Student Association.

Dwight’s mother came to the U.S. as a refugee in the second wave of boat people. Her dad and seven siblings attempted to flee from the communist-controlled North several times. The sea insisted they stay home each time, but finally in 1978, the waves of the Pacific granted their voyage to Bidong Island, a large refugee camp in Malaysia. From there, getting to the US was the obvious choice for Dwight’s grandfather. It was the American Dream. Golden ticket.

“They eventually were sponsored by a Methodist church in Michigan. This is why we’re here. We celebrate Lunar New Year and do all those things at home. I’ve still got a Paris By Night VHS. It’s in my mom’s cabinet,” Dwight says of growing up Vietnamese in America.

For many of the first generation of Vietnamese American children, a degree from a higher education institution is the default route to success. As noted in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Pulitzer prize winning novel The Sympathizer, “We don’t succeed or fail because of fortune or luck. We succeed because we understand the way the world works and what we have to do. We fail because others understand this better than we do.”

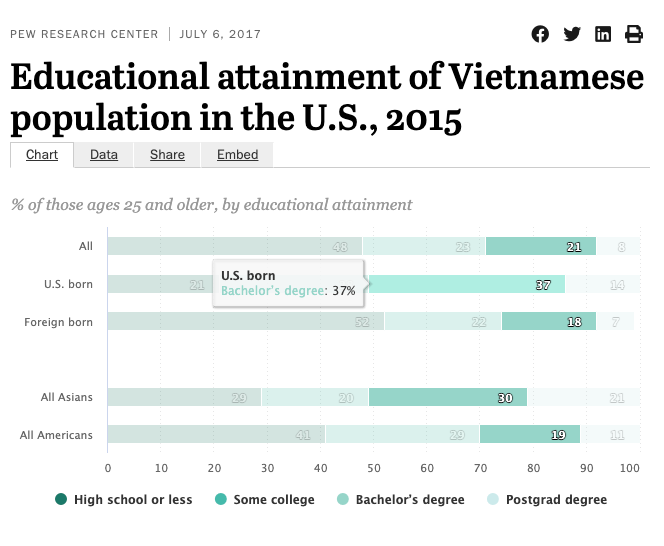

Out of all Americans, 30% of the population obtain a bachelor’s degree. In a study about the education attainment levels of the Vietnamese population in America, Pew found that of those who are U.S. born, 37% obtained a bachelor’s. What they might not expect is that college comes with more than just textbooks.

In 2019, Hua led SVSA to join the Tibetan and Hmong student clubs in a campus campaign to disaggregate Stanford’s admission data, which found 22% of students to be Asian American. They urged for data on students to specify identities more narrow than “Asian American” so cultural student organizations could figure out how many of their community members made up the student population and adjust outreach efforts appropriately. These efforts were to include, if applicable, aiding commuters with transportation costs or reaching out to prospective Stanford applicants.

Hua described the aim of the campaign to be “combating that model minority myth. College admissions have been like, oh Asian Americans are doing fine. In reality, Southeast Asians have very disparate experiences; in terms of income level, in terms of access to education, and all those different factors.”

However, many of the equity strategies employed by Hua and other advocates reflect mutual aid and resource distribution practices encouraged by the very politics their families sacrificed most everything to escape from. Ideologies like communism were used to justify atrocities in their parents’ home country. The gap between theory and practice then becomes quickly personal, close to suggesting that the man with a smoking gun could be family.

For Hua, college was a racial reckoning. Stanford was nothing like the small town, predominately white schools he was used to attending in Grand Rapids, MI. He launched himself into being actively involved with his Vietnamese American identity, along with accompanying larger movements of collective liberation for Asian American communities and BIPOC communities.

On a more intimate level, this retracing of steps led Hua to deeper converse with his mother. She tells him of her experience being an Asian American woman, as the third eldest daughter, and of her own contentions with family. They reflect on what it means to be Vietnamese American, contemporarily. He’s not sure those conversations would’ve been possible had he not been exposed to curriculum that addressed broader political and community issues.

Those broader issues include global conflict ongoing today. When all eyes were on the city of Kabul last year, captured by the Taliban and indicating the end of the War in Afghanistan, news iconography mirrored those of the fall of Saigon.

Footage of Afghans chasing after a U.S. Air Force aircraft is reminiscent of Hubert Van Es’ infamous 300 mm photo of a CIA member helping evacuees climb a ladder onto an Air America helicopter on the roof of 22Gia Long Street. April 29, 1975 marks when Saigon was doomed to be renamed Ho Chi Minh City, four days after my mother was born.

Both images are about anything but defeat. Moments like Saigon and Kabul remind us of the necessity of humanitarian aid on the singular and global level.

A hand holding out a hand.

From old polaroids to iPhone 11 footage, Vietnamese American imagery is in well abundance. To celebrate a birthday, a childhood, a family, or a home is to secure it in amber. Look at us, please. We’re human.

It would be easy to create enemies with abstract ideology, to encourage communities reckoning with trauma to villianize concepts on paper instead of holding politicians responsible. It would deny relations. That we’re really all just relative to each other. But when we are face-to-face, the first curiosity is practically universal – what’s your name? I’ll tell you about all those before me who share mine. Maybe someone will relate this way.