Se tiver consentimento, é pedofilia? If there is consent, is it pedophilia?

A question so ludicrous, so blatantly gross, it makes your stomach turn. Pedophilia and consent. Terms that are never intertwined. This can’t be a real question. Right? Right? Nobody of sane mind would ever make a comment questioning consent when it comes to a child.

And yet, in the fall of 2015, Valentina Schulz, a Brazilian child from São Paulo, whose passion and aptitude for cooking compelled her to sign up for Masterchef Junior Brazil – the children’s version of the popular culinary reality show – found herself caught in a maelstrom of sexual harassment of pedophilic nature, fueled by social media comments like the one above.

Valentina was 12. Yes, twelve. A time young girls might spend at sleepovers with friends, braiding their hair and giggling about their favorite celebrities. Or time spent shuttling between sports practices and the local middle school. Not time spent being barraged with obscene comment after obscene comment, each insinuating what these men – some nearly triple her age – thought of her body, her face, her blonde hair.

Sexual harassment at any age hurts. Sexual harassment at any age is wrong. But experiencing sexual harassment during childhood is a kind of trauma that’s especially difficult to unpack, to barrel past, to roll your eyes and shake off.

As reported by faculty in the department of psychology at the University of Gothenburg in a longitudinal study of childhood sexual harassment published in the BMC Psychology journal, experiences with this trauma can bring about “lower self-esteem, poor physical and mental health, and trauma symptoms, shame, poor body image, depressive symptoms, substance use, adjustment problems, and academic problems.”

And experiencing this trauma during childhood very well may provide new challenges, as the victim might not even understand what’s happening to them. In the case of a 12-year-old girl, her understanding of sexual harassment would differ from that of a college student, and even more so of a middle-aged woman.

So before Valentina could even begin to heal, to raise her head and move past the harmful tweets, she would have to learn. Learn what sexual harassment implied. Learn what rape meant. Learn what consent was.

“There was a group of men insinuating things about my body, who were literally threatening my life,” Valentina, now 18, wrote in an open letter, penned last year for UOL, a Brazilian digital media site. “There were even people saying that if they ran into me on the street, they would kidnap me.”

How does one even begin to move past that? How are you, as a middle schooler, expected to return to your normal life, when in the back of your mind, the threat of these grown men perceiving you, judging you, possibly even harming you, sits.

“There were even people saying that if they ran into me on the street, they would kidnap me.”

Unfortunately, Valentina’s story is one that Brazilian women know all too well.

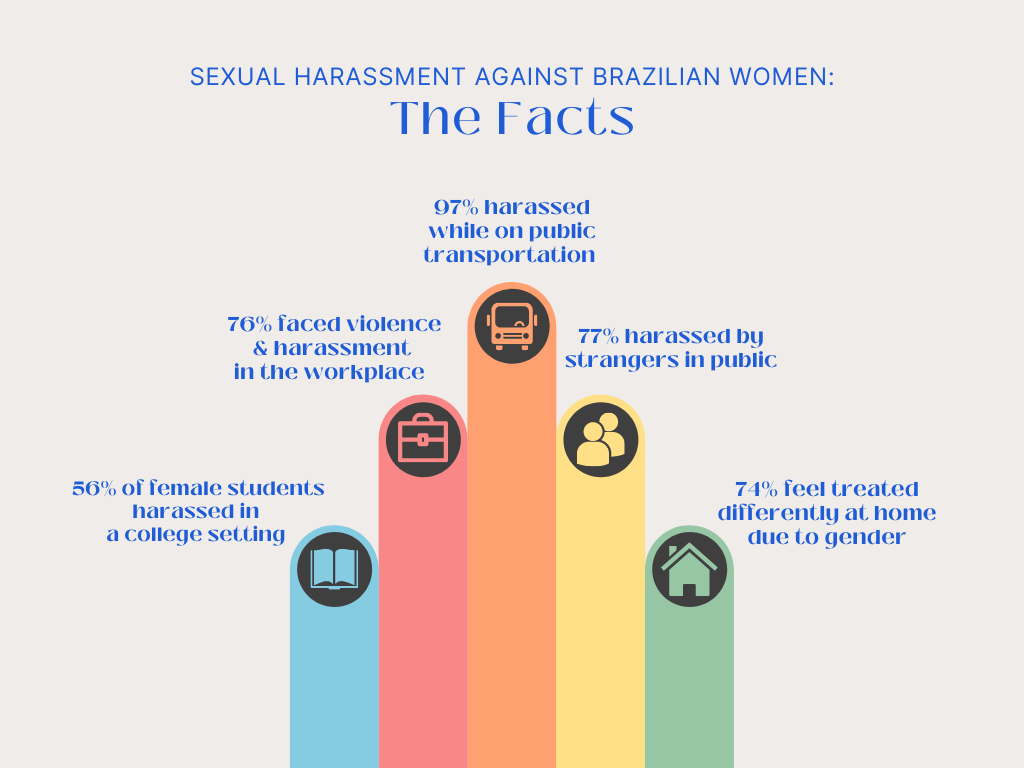

A study conducted by the Patricia Galvão Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to women’s rights in Brazil, found that 97% of Brazilian women have been victims of sexual harassment while riding public transportation. Nearly half of the women who participated in a survey conducted in partnership between LinkedIn and social innovation consultant Think Eva – associated with the feminist collective Think Olga – responded that they had been sexually harassed in the workplace. The most reported forms of harassment in the survey were solicitation of sexual favors, unwanted physical contact and sexual abuse.

While numbers and statistics don’t lie, neither do the personal stories of the thousands of women who began sharing their experiences with the hashtag #MeuPrimeiroAssédio – my first harassment – following the release of the first Masterchef Jr episode, seven years ago.

The social media campaign was started by Juliana de Faria, the São Paulo-based journalist behind the feminist collective Think Olga which was founded in 2013 with the intent of “empowering women through education”, who became outraged by the comments being made.

One by one, the posts started pouring in. Accounts of sexual harassment and abuse endured by women throughout their childhood and teenage years flooded Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp, putting living, breathing names and stories to data that had been previously collected. By the fifth day of Think Olga’s campaign, there were over 80,000 tweets and retweets using the hashtag –– a clear indication of just how widespread Valentina’s experience was, and still is, in Brazil.

“It has taken me a long time to realize that the harassment we are experiencing is not something personal, but political,” de Faria told Vogue Brasil in a 2017 interview. “And the men who violate these women aren’t monsters who are distant from us. They’re men with PhDs, with wives and kids.” In other words, the culture of sexual harassment in Brazil doesn’t exist exclusively in the extremes; it lives and breeds in daily life, perpetrated by the father next door or the boy sitting by your desk in class.

However, the commonplace-dash-virtually universal nature of these occurrences doesn’t make the experience any less uncomfortable for young girls. Just because something happens often, doesn’t mean the trauma is any less. Take the University of Southern California for example, where the 2019 AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct discovered 54.8% of undergraduates have experienced sexual harassment while at USC. The prevalence of this behavior on campus doesn’t minimize each individual’s experience.

“And the men who violate these women aren’t monsters who are distant from us.”

Brazilian-born Sofia Fruet, a USC senior, spent most of her childhood and adolescence in São Paulo, a sprawling metropolis with over 12 million residents where 63% of women in the city reported facing some form of sexual harassment in 2020, according to a study by Rede Nossa São Paulo. She recalls that the harassment began for her around the same time she started high school at age 14. And from then on, it never ended. As the years went by, the whistles and stares and leering all began to blend together, her skin growing thicker and her ears developing selective hearing as she walked through the streets with her friends.

However, one specific incident sticks out to Fruet as particularly unpleasant.

She was leaving school one day to grab a quick bite before her afternoon volleyball practice, backpack hung lazily over one shoulder with not a care in the world, when it happened. Fruet was mere paces away from her high school’s campus as the catcall was shouted –– piercing the air and knocking the wind right out of her, in the way only unexpected verbal abuse can. Much to her dismay, this incident had an audience. Some of her teachers and peers were gathered at the front of the school and witnessed the scene.

“That was a particularly rough one being that it was in front of a bunch of people that I respected,” said Fruet, trailing off and staring intently at the corner of the Zoom screen, perhaps replaying the memory in her head. “It’s weird to have people see you vulnerable like that.”

Yes, it is strange to have the people who have known you as essentially a child perceive you as being the target of somebody’s abuse, of their lewd comments and wandering eye. It makes you feel icky, like a stain you can’t remove no matter how hard you scrub or the nausea in your stomach that persists even after you down that glass of ginger ale. But despite this unrelenting feeling, Fruet knew that there wasn’t much she could do in that moment besides put her head down and keep walking.

“Growing up you kind of just learn that it’s a nuisance that you just deal with, unfortunately. It just becomes another part of your life that you have to get through,” she explained.

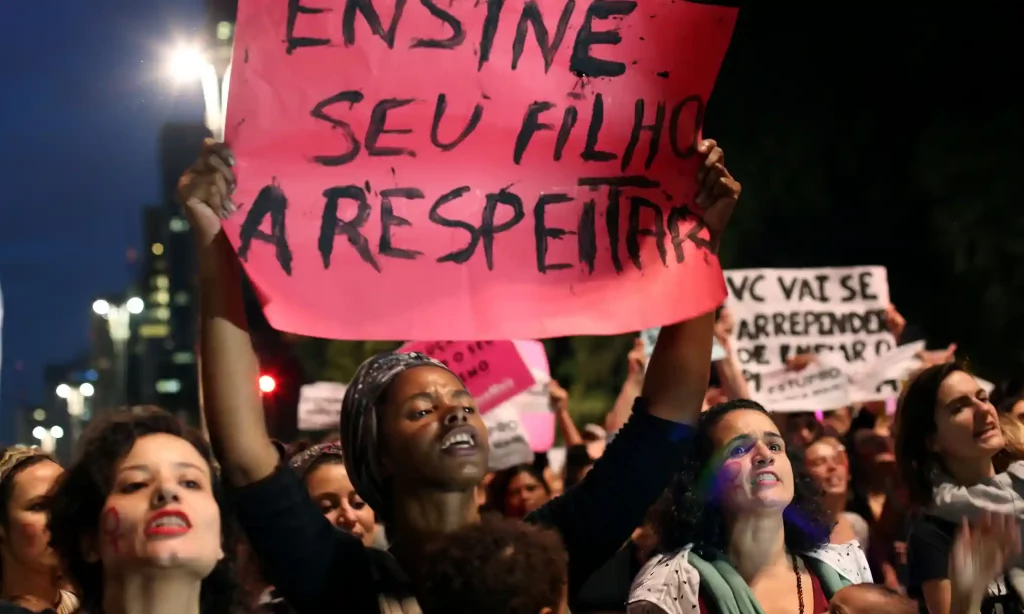

But acceptance of sexual harassment as just another part of life as a woman is no longer seen as the inalterable status quo in Brazil. From social media campaigns like #MeuPrimeiroAssédio to the dissemination of feminist journalism, change, pushback, progress – whatever you want to call it – is happening. Yes, the road to proper and just treatment is long and arduous and complicated, but the circumstances the modern Brazilian woman faces today are significantly different than those of the 20th century. Nobody is more aware of that than the women who have watched the culture slowly, but surely transition over decades.

“Growing up you kind of just learn that it’s a nuisance that you just deal with, unfortunately. It just becomes another part of your life that you have to get through.”

Fifty-nine-year-old Junia Santos, a child-care provider, was born and raised in Belo Horizonte before immigrating to California in 1995. Her first encounter with sexual harassment came at the age of 10, two years younger than Valentina Schulz was when she went on Masterchef Jr. Santos is a woman whose experience with frequent harassment heavily influenced the way she chose to lead her life and the knowledge that she imparted on me, her daughter.

My mother’s nuanced understanding of the issue derives from both her time spent living in the culture, where she learned to identify where this behavior comes from, and her time spent living abroad, returning every couple of years as an outsider looking in.

“It’s about educating the culture,” she told me recently, sitting in our kitchen in the Bay Area. “Men in Brazil need to learn how to treat women, how to respect women,” said my mother. “Not all of them, but most of them never learn as little kids how to treat women, so they grow up not seeing it as disrespectful to behave like this. It’s a total lack of education, in my opinion.”

Proper education appears to be one of the most established solutions proposed by those in my mother’s generation, like my aunt Valeria Santos. Despite the four year age gap between her and my mother, how they view the answer to sexual harassment in Brazil remains the same.

“There are many factors involved in changing an entire culture and bad behavior,” explained my aunt, the enthusiasm rising in her voice as we spoke on the phone one afternoon. While my mother is known for her calm and quiet demeanor, my aunt lives on the other side of the spectrum –– exaggerated hand gestures and loud intonations color my conversations with her.

“Information and education are basic keys for all human transformations,” she continues. “This particular change is dependent on the will of women, the help and resources of the community and the Brazilian government.”

“Information and education are basic keys for all human transformations.”

To some degree, there has been a change in the education, especially from women working to combat sexual harassment in their society. Whether it be larger group efforts through social change initiatives like Think Olga or individual women calling out problematic behaviors that they see in their daily lives, women are no longer allowing for this toxic culture of sexual harassment to persist in Brazil.

For those in my mother and aunt’s generation, they had yet to see a society of women who were as unafraid to stand up for themselves like this current generation.

“When I was a little girl, we didn’t have the strength to fight or to create campaigns against sexual harassment,” my mother told me, raising her shoulders ever so slightly while leaning back in her chair. “Nowadays, everybody talks about it. Most people have the understanding that this is bad behavior that needs to be stopped.”

And this is true.

The conversations today in Brazil about its misogynstic culture and sexual harassment are undoutbedly more progressive than what was being discussed seven years ago when #MeuPrimeiroAssédio was trending. Feminism is seen less and less like an act of radicalism and more as the innate right of each and every women. This shift could be attributed to a variety of different factors: pushback to the controversial election of President Jair Bolsonaro, whose highly misogynistic rhetoric shocked women across Brazil, an increase in participation in activism by way of social media or simply society becoming more and more progressive – nearly 50% of women aged 16 to 35 consider themselves feminists, according to a Datafolha survey in 2019. While this number may seem small, it’s significant in a nation where the word “feminism” has often been spat out like a curse in the past.

As activists in the country attempt to move forward and away from the culture of catcalling and harassment, progress has become reliant on the ability of women to rise above.

“In the past when I was a little girl, we didn’t have the strength to fight or to create campaigns against sexual harassment.”

For Valentina, the little girl who had her childhood stripped of her by harassers on the Internet, she was able to rise above by using her voice to empower other women who’ve experienced similar harassment and working to change the narrative surrounding her. She’s published a book titled O Diario de Valen or “Valen’s Diary,” has worked on a variety of community efforts and boasts over 2 million followers on Instagram. She now understands the importance of transforming the platform she once received under unpleasant circumstances, into an influential way to discuss matters of feminism and women’s rights.

Discussions of feminism in modern-day Brazil are also facilitated by the women in journalism who are dedicated to unmasking – and eliminating – the culture of sexual harassment one story at a time.

Fernanda Santana is a reporter at the Jornal Correio da Bahia, the most circulated newspaper in northeastern Brazil, who graduated from the Federal University of Bahia in 2019. Despite her young age, Santana has already made a name for herself, winning the Prêmio Semear Internacional de Jornalismo last summer –– an award for journalistic works that highlight positive agricultural practices taking place in rural Brazil. Her award-winning story “Pérola do Sertão” or “Pearl of the Backcountry,” chronicled how women in rural Bahia are working to reestablish their local economy post-COVID, so she’s no stranger to female-driven journalism.

“Feminist journalism or media that’s directed by women can be essential from multiple perspectives,” said Santana. “It can result in a more diverse team, it can bring about the inclusion of agendas that more frequently address gender discrimination and it can even show perspectives that only a woman can share with the another.”

All of this rings true. Feminist journalism generates important conversations surrounding topics of diversity and discrimination, while serving, naturally, as a form of pushback to the toxic culture of harassment found in Brazil. Without women in the media standing up and telling their stories, it would be a markedly different media landscape, similar to the one my mother and aunt experienced during their childhood and adolescence.

However, feminist journalism still stands out due to its progressiveness – this is in no way the norm.

As we got deeper into our conversation, Santana told me about a piece of journalism which she’d encountered a few years ago that blatantly promoted sexual misconduct. A local television station had made a report with the following poll: “Are you in favor or not in favor of forced kissing during Carnaval?’’ In other words, are you in favor of sexual assault? “The journalist even reported the results later, as if harassment or rape were matters of opinion and the highest ranked opinion had won,” said Santana, her eyes widening incredulously. “How could such a poll have been aired and who thought of its existence?”

It’s moments like these that remind us why we need feminist journalism in the first place, why we need women to fight back, why we need to properly educate and remove this culture of sexual harassment from the streets of Brazil.

“The journalist even reported the results later, as if harassment or rape were matters of opinion and the highest ranked opinion had won.”

Will it be easy? No, not in the slightest. Dismantling a behavior pattern that has permeated into almost every facet of Brazilian society since before my mother was a child in the 60s doesn’t just happen overnight. There are mindsets to shatter and policies to instate. But change is possible.

As my generation is better equipped to fight back than my mother’s was and as hers was better equipped than her mother’s, I hope to watch my future daughter’s generation and marvel at how they fight back.

With each generation, each hashtag, each story told, we find ourselves inching closer to a future where sexual harassment is merely a ghost from Brazil’s misogynistic past.