How domestic violence incidents in Los Angeles have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

1. Data findings

Since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in March 2020, LAPD Domestic Abuse Response Team (DART) has received more service calls related to domestic violence per day than pre-pandemic, according to the LAPD publicly available crime dataset.

Before March 2020 when Los Angeles county ordered city-wide lockdown due to the pandemic, the team received 110 service calls per day; but starting from March to December 2020, the team received 122 serve calls per day.

“We were starting to see a decline before the pandemic and we were hoping it was because we were starting to do something,” Marie Sadanaga, the coordinator of LAPD DART, said. “When this pandemic happened, we started to see an increase in calls.”

When the pandemic restrictions were gradually lifted in 2021, domestic violence crimes decreased 7.4% according to LAPD DART. Domestic violence, however, is still a serious crime in Los Angeles. Data shows that corporal injury on spouses and co-habitants is the second most type of arrests, which have 4,081 cases.

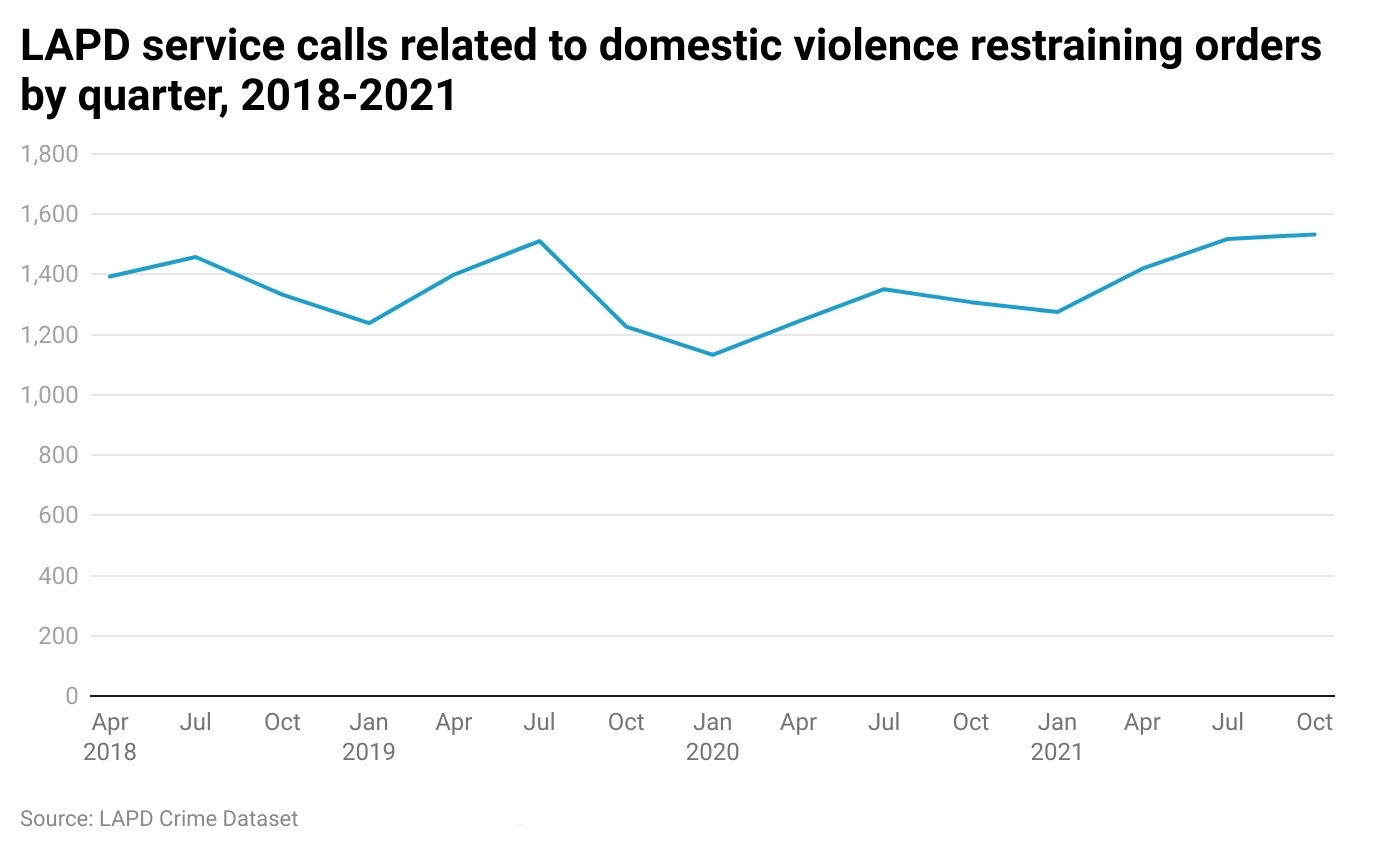

The court-issued restraining orders are often considered the best protection survivors of domestic violence can get to shield them from their abusers. The number of service calls related to domestic violence restraining orders that LAPD received has increased since the start of the pandemic.

In 2021, LAPD continued receiving more service calls related to domestic violence restraining orders. The last two quarters of 2021 had the highest ever numbers since 2018.

Sadagana explained that since the courts had been closed for a while during the pandemic, the cases filed up fast were hard for the courts to quickly address, which leads to increased calls regarding restraining orders.

2. Factors driving the slight increase

According to research conducted by the University of Miami, domestic violence cases had increased 8.1% nationally after the implementation of stay-at-home orders.

The research shows that the pandemic has led to “increased unemployment, stress with healthcare and homeschooling and increased financial insecurity.” All these factors are associated with domestic violence, according to the research.

Furthermore, the research points out that the stay-at-home order places abusers and victims within a physical location isolated from the outside world, which also increases the risk of domestic violence. According to the research, connection with the outside world matters a lot because the victims’ network with friends, relatives, or teachers may be able to offer help.

In Los Angeles County specifically, Debbie Murad, a professor at the USC Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, agreed with the research. She pointed out that more time spending at home has led to more severe and frequent domestic violence incidents during the pandemic.

“If the abuser was struggling during the pandemic, that person is going to take it out on the family, and basically they have more time to terrorize the family,” Murad said.

Murad also pointed out that during the pandemic victims have been less likely to report the abuse cases, because there is often no separation between the abusers and victims.

Since there’s been a greater level of difficulty for the victims to call the police, Sadagana said LAPD recommends victims to text in either English or Spanish to 911.

She further pointed out that there have been difficulties analyzing what factors exactly had led to increased domestic violence cases, because the workload of analyzing every single service call could be incredibly large.

In terms of why the increase of domestic violence in Los Angeles County during the pandemic is only a slight increase, Sadagana mentioned that since nearly everyone stayed at home under the lockdown order, there have been more mistaken calls that come from neighbors who happen to hear fierce fighting or arguments.

“Especially if you live in a multi-unit complex, either apartments or condos, you’re hearing more arguments than if you were out. So it could be other people calling in and it turns out it’s not domestic violence,” Sadagana explained. “Also, you have the whole family at home with multiple callers for the same incident.”

In other situations, there have been mistaken calls where people in a long-term relationship call in LAPD before the domestic violence actually happens, driven by the increased stress during the pandemic, according to Sadagana.

“All of us were tired of being at home and everyone was getting on each other’s nerves. People started calling before there was a crime,” Sadagana said. “Sometimes the survivor calls before it gets there, and when the police respond, they’re able to defuse the situation.”

3. Other patterns of domestic violence case

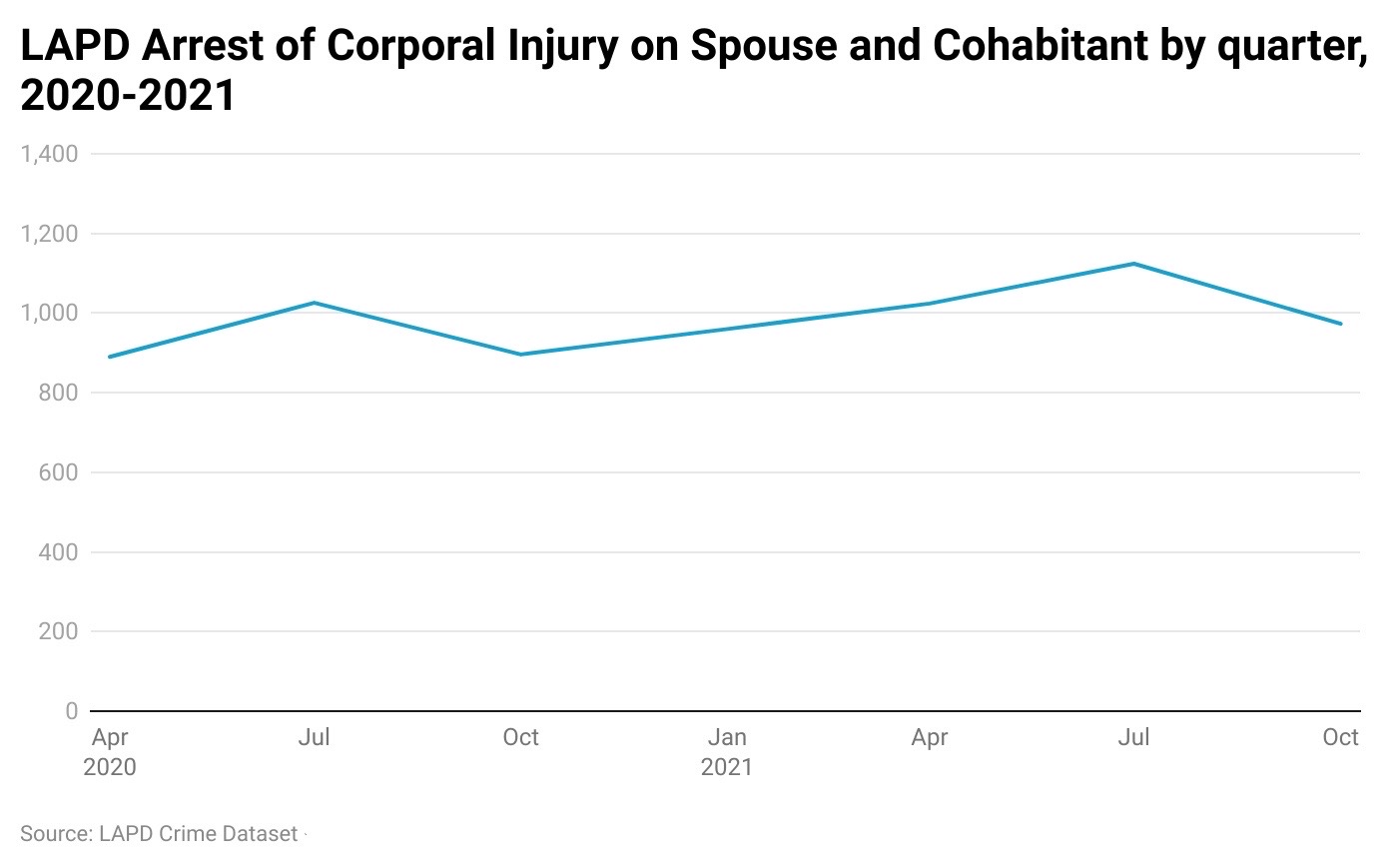

In addition, the third quarter of 2021 has the highest number of arrests for corporal injury on spouse and cohabitants since the fourth quarter of 2019. The number of arrests for corporal injury on spouse and cohabitant peaked at the 3rd quarter of every year.

Similarly, the number of service calls related to domestic violence that LAPD DART received also peaked at the third quarter of every year. Sadanaga explained that such a repetitive cycle can be attributed to more crimes generally happening in summer every year driven by warmer weather and longer daytime.

“Since I came on the job, [the peak] happens always during the summer, and we even see increases in just general violent crimes like robberies and shootings,” Sadanaga said.

In addition to the frequent incidents in summer, Sadanaga added that domestic violence incidents are more often to occur during holidays, since the team has received a lot more calls on Christmas Eve, Thanksgiving, and so on.

The LAPD dataset states that other peak days include the day after Independence Day (July 4) and Halloween.

Furthermore, Sadagana says that late afternoons and evenings of a day is are when domestic violence cases happen most frequently because people start to come back home during those hours.

4. Help from police and non-profit organizations

Sadagana explained the procedures of how police respond to the service calls. After receiving the call, patrol officers are assigned to the radio call. Once they’re there, the officers separate the parties and ask them both what happened.

“There are multiple sides to every story, and if we determine that there was a crime of domestic violence, then we will arrest the suspect [on spot]. That’s mandatory. And then if the suspects have left, we take a crime report,” Sadagana mentioned.

The police officers would also consider subsequent treatments or services if necessary, such as whether an emergency protective order is needed, and whether the victims need to be provided shelters to stay, and so on.

CarolAnn Peterson, an appointed member of Los Angeles Mayor’s Domestic Violence Steering Committee as well as USC adjunct professor on domestic violence, said that victims may also call the National Domestic Violence Hotline, which can direct them to emergency shelters.

The shelters could provide clothes, food, legal services, counseling, peer support groups, and so on, according to Peterson. Some centers such as the Family Justice Center provide all those services in one building.

“The agencies would work with victims to help them find the housing after they move out of the transitional housing,” Peterson said.

Peterson said that the non-profit organizations have become more straightforward and specific when reaching out to the victims for providing help.

“Instead of asking how they were in general, [organizations] began to ask ‘do you need something, such as diapers or water?’” Peterson said. “Reaching out in that sense gave victims a chance to get the things they needed.”

In addition, non-profit organizations have become more proactive in finding victims than before, according to Peterson. For example, the organizations may go to the food pantries where they put out the information of how to seek help for the domestic violence victims at their own tables.

“It became really thinking outside the box,” Peterson said. “If victims were shopping by themselves, they had the ability to talk to somebody [from the NGOs] to pick up information and look at it and read it.”

In addition to the creative ways where the NGOs reach out to the victims, the NGOs’ members also teach victims to protect themselves and not to disclose their communications with the NGOs or police. The pandemic has also driven victims to text to their relatives or friends who text to 911, Peterson said.

“We knew victims who were in the bathroom looking up organizations on their cell phone, and we taught victims how to get rid of their history on their cell phone or computer,” Peterson introduced. “When victims text the organization saying, ‘I’m a victim, and what can I do to stay safe?’ The agencies would text back and then remind them to delete all of this off their phone.”

From Peterson’s social work experience, she found that the restraining orders sometimes may escalate the violence, and the agencies’ staff should always defer to the victims’ own choice.

“If a victim says they can’t get an order, what they’re telling you is that they’re afraid this will escalate the whole entire incident. They’re a better judge of what was happening,” Peterson said.

Furthermore, Peterson pointed out that if victims are determined to leave the houses, agency members would always caution them to prepare a thorough safety plan, because some abusers will stalk victims after they have left. Peterson mentioned that a lot of victims die within two years of having left.

“We never tell somebody that they have to leave an abusive relationship, and every victim leaves in their own time,” Peterson said. “It’s also a question of letting victims know that we’re not being judgmental…They’ve already got that authority figure at home, so it’s our job to help them make decisions that work best for them and keep them safe.”

5. Healthy close relationships

Exerting control is at the root of many domestic violence cases, Peterson said. Some abusers have grown up in violent households and never experienced healthy relationships.

“Abusers view the world as if everybody owes them something and especially a significant other,” Peterson said. “They really truly believe consciously or unconsciously that this person is a piece of property that belongs to me.”

Wang “Xin” is a communications major student at USC. She said after taking the course on interpersonal communication and reading books about close relationships, she has gradually grasped the essence of maintaining a healthy close relationship especially during the pandemic when everyone is loaded with stress.

“I’ve learned in class about the theory of ‘four positives versus one conflict’ which means that a close relationship can have four happy things and one divergence in a certain period of time,” Wang said. “I realized that the conflicts are unavoidable, and what matters is how we solve the conflict.”

Wang said she values keeping each other’s boundaries in daily life and not trying to control others’ behaviors.

“Ultimately we are still independent individuals no matter how close we are,” Wang said. “We should also respect each other’s own boundaries and comfort zones instead of treating each other as our own properties.”