Gen-Z grasps at their fleeting agency by embracing permanence.

by: ana mata

Awo Jama has drawn on all of their clothes for as long as they can remember. They wrote their name on everything, added stickers to adorn simple pieces and did experimental makeup to spice up a dull look.

From using colorful eyeliner to adding gems to their cheekbones, Jama always wanted to push the limit on how they expressed themselves. Sometimes, it didn’t feel like enough.

“I just kept having this image when I picture my ideal self and the person I wanted to grow into: me having something, whether it was a drawing or some words, tattooed on my face,” Jama said. “I kept seeing that visual when I would daydream about the person I think I’m going to grow into.”

After watching a documentary on the English designer Vivienne Westwood and “seeing how Vivienne Westwood just embodied exactly who she wanted to be in the way she dressed and the way she moves with the world, something clicked.” Jama booked a tattoo appointment for a couple days later.

Adorning Jama’s right cheek are now the words “happy happenstance” in curly red ink.

The line from “Cajebey” from the Somali poet Hadraawi — “Cawo iyo ayaaneey” — loosely translates to “happy happenstance and fair fortune” in English.

Jama and their close cousin’s name are found in the original line of the poem. They said it was a big influence in their decision to get the tattoo.

“Our names loosely translate to ‘a gift’ or ‘good fortune that can only be explained by something God given’ and that’s kind of why our moms chose our names to go together, so it was just really meaningful to me,” Jama said.

Though the story behind Jama’s first tattoo reflects the deep contemplation and personalization behind choosing something that will be on your skin forever, for much of Gen-Z this isn’t always the case. But similar to Jama, these decisions are often made spontaneously.

From makeshift studios in the corner of a bedroom to the middle of a living room as a house party dies down at 2 a.m., young people are immortalizing moments with the help of tattoo guns and stick and pokes.

Amanda Sanchez, a junior at USC majoring in music industry, integrates her love of tattoos into the work she does putting on concerts — often in the backyard of student residences. She will hire local independent tattoo artists as vendors at these shows and the artist will typically create a “flash sheet” that clients can choose from.

“I think a lot of people that come to those shows are living in the moment and embracing their artistic side,” Sanchez said. “So it just kind of works out.”

One of Sanchez’s favorites of her own tattoos is the small bat she got at an event she threw.

“Now, I try to justify it like ‘Oh, because my first show was a Halloween show,’ but that came after. I was really just like ‘Oh that bat is really cute’,” Sanchez said. “I like having something that kind of represents who I am at the time.”

It’s just my brain gunk on paper and then on someone’s body later on. I get to hear their feedback and it’s like what kind of aesthetics they lean towards. Some people are more curvy and flowy, some people are more spiky.

Selin Aydin, independent tattoo artist

The desire to commemorate moments and versions of oneself is becoming more and more popular among young people, according to Naomi Nembhard, who proudly reps their twenty-something tattoos.

“I think definitely when I speak to younger people, queer people, people who are tattoo artists or get a lot of tattoos, [people] that are kind of in similar spaces that I find myself in, a lot of people identify with that same sentiment that it doesn’t have to have some huge monumental, poetic meaning,” Nembhard said. “It’s just something to you.”

For many young people, it’s a way to display their value of art in a personal way.

“I think it’s such a beautiful thing that we use tattooing as an appreciation of certain art forms. The art of tattooing being one, but also just of fine art, even like typography or drawing, painting,” Jama said.

For the tattoo artists themselves, this appreciation for art is a two way street. Selin Aydin, a senior at USC pursuing a fine arts degree, recently took up tattooing to explore another medium.

Aydin said that when she makes art for a gallery setting, she’s ultimately making art for herself. With tattooing, she can share her work in a way that’s much more accessible.

Not only are the designs themselves a vehicle for her to employ her oil painting origins, — she said that “everything I do, I view it as a painting” — but the exchange and collaboration a tattoo requires is what makes it so special to her as an art form.

“It’s just my brain gunk on paper and then on someone’s body later on. I get to hear their feedback and it’s like what kind of aesthetics they lean towards,” Aydin said. “Some people are more curvy and flowy, some people are more spiky and it’s also just like me kind of personalizing it to whatever I think their vibe is and that’s how I’ll initially draw it.”

The connections that tattoos form can go beyond that between artist and client, Sanchez said.

“Instead of buying a picture that you hang on your wall forever, it’s on you forever. Which I think is beautiful because it kind of connects us. One of my tattoos is flash, so there’s someone else that has it,” Sanchez said. “My artist was like ‘Oh this last person just did this in the same spot on their other arm. Like I don’t know this person but I feel connected to them.”

For Zoe Alameda, also a senior majoring in fine art at USC, she said that picking up tattooing as a medium has allowed her to grow beyond her other forms of creative expression.

“It’s also sort of like a therapy because I can do a lot of overthinking with my big, main practice pieces, but when it comes to tattooing, everything’s more immediate and I would say even more forgiving,” Alameda said. “I know you’re making permanent decisions on people’s bodies, but I feel more confident in doing that because it’s such a quicker process.”

Similar to the happenstance scribed on Jama’s cheek and that of the decisions for Gen-Z to get tatted, the way many artists enter the world of tattooing is on a whim.

Tattooing found Aydin when she was drunk with friends at five in the morning. Her friend had a machine bought off of Amazon — “it was really janky, like a cardboard box” — and she simply leaned into the moment.

“I WikiHow-ed it — or I skimmed it — and then I did it and it was really shitty. But that was kind of such a rush and I was like ‘I need to keep doing this,’” Aydin said.

Alameda described a similar initial experience and said that having friends in the industry influenced their decision to pick it up as a practice. Their work focuses primarily on feelings of anxiety, being overwhelmed and longing to find deeper connections within ourselves. They said tattooing has fit perfectly into their narrative as an artist, despite maintaining their mediums of choice: collage making, printmaking and sculpture.

“Personally in my work, I talk a lot about identity and just trying to be comfortable within yourself. So, I think tattoos sort of align in that decision making to have something be on your skin forever; it’s just something I’m always sort of thinking about anyway,” Alameda said.

The decision for artists of various mediums to pick up tattooing is not surprising considering the increase in popularity of the field as a whole over the last ten years.

“All of those concerns that people love to bring up as kind of the excuse to tell people not to get tattoos, I don’t think any of them have much real foothold on actual reality,” Nembhard said. “It’s all rooted, I think, it attitudes 10 years ago or 20 years ago.”

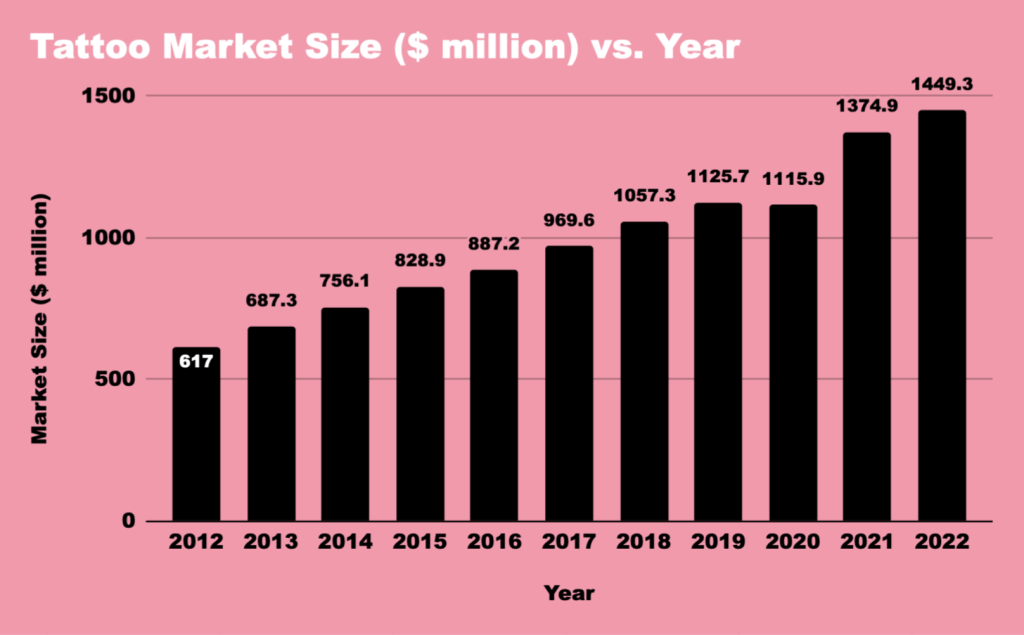

According to IBISWorld analysts, the market size of the tattoo artist industry in the United States grew from $1115.9 million to $1449.3 million from just 2020 to 2022. The market size of the tattoo artists industry in the United States has grown 8.4%, on average, between 2017 and 2022.

In addition to the increase in nihilistic tendencies of young people following the coronavirus pandemic, this increase in tattooing can be partially attributed to queer people’s desire to create a home within their bodies.

“It gives, at least me personally, something to look at on my body and be happy about and think is beautiful,” Nembhard said. “Being queer, being non-binary, I think it’s an amazing thing that exists to be able to do. It sort of seems like a simple thing and then another way it feels very complex. Either way, I think the fact that it lets me be happier with the way that I look is an amazing thing.”

Those who have tattoos are familiar with the probing questions wondering ‘What’s the meaning?’, ‘Why did you pick that as your first one?’ or ‘Why would you ever get that on your body?’. Alameda thinks that this applies too much pressure.

“I get it, but I think you shouldn’t be so hard on yourself. Collecting things that you love over time is a very fun, nice way to love yourself,” Alameda said. “I think it’s nice that I could give people that option. Just the silly nature of a quick five minute scribble forever being on you is like a breath of fresh air.”

Jama, who is Muslim, is also familiar with external influences on their perception of tattoos. In Islam, tattoos are prohibited because it prevents the individual from being entirely clean, which is required in order to pray. Jama also said tattoos are seen as destroying or altering the way God intended your image to be.

“I am very religious, very spiritual and respect my religion a lot, respect Islam a lot,” Jama said. “I think where I’m at right now, I just kind of want to do things that bring me euphoria in terms of how I present myself to the world, like bodily euphoria.”

For Jama, getting tattooed for the mere sake of loving yourself is almost a radical decision now, considering the increase in laws policing bodily autonomy.

“Whether that’s who we love or our choices to reproduce or not reproduce, these systems are literally just policing our bodies and telling us what we should be doing,” Jama said. “Our bodies are ours at the end of the day. They belong to one person; that’s us and we should be able to decorate our bodies or show our bodies love in different ways that we see fit.”

“I think where I’m at right now, I just kind of want to do things that bring me euphoria in terms of how I present myself to the world, like bodily euphoria.”

Awo jama, Los Angeles resident

The desire for bodily autonomy is congruent with the desire for autonomy from tattoo artists themselves. Many artists of various mediums are opting to become independent tattoo artists because of the flexibility and control over both their income and workspace, often choosing to not work in a traditional shop.

“There still are pluses to it because with tattoo shops, they supply everything and you have the space to tattoo, but they also do take 50% commission,” Aydin said. “The tattoo shop environments are pretty toxic, I’d say, in terms of they’re very male dominated … It’s pretty hard to get into a shop and it’s very intimidating as well.”

In addition to an increase in control over one’s space as an independent artist, Aydin said that since she works out of her bedroom, she’s able to curate the entire tattoo experience for clients.

“I’ve heard back from my customers or my clients being like ‘I feel so comfortable here, more comfortable that I would be at a shop.’ That’s especially from the women that I’m tattooing,” Aydin said. “In a shop, you’re kind of exposed on the table because there’s usually rows of tables, where here it’s like the corner of my room, little fairy lights, we’re playing music, we get to chat, I’ll burn incense.”

To get licensed as a tattoo artist, there are three steps: a blood pathogens training, an up-to-date Hepatitis B vaccination, and a fee. Licenses are primarily required when an artist wants to work in a traditional shop, but since more and more artists are opting to be independent, many forgo the certification due to the cost.

“As long as you have the training and all the health precautions which are super important … it’s just sort of, ‘What’s the point of paying if I’m not even needing it?’” Aydin said.

The access of independent tattoo artists is just one attraction for many young women and non-binary people. Primarily, it has to do with feeling safe and comfortable in a space that has historically been tailored to men.

“Our bodies are ours at the end of the day. They belong to one person; that’s us and we should be able to decorate our bodies or show our bodies love in different ways that we see fit.”

awo jama, los angeles resident

“The experience with tattooing is literally being stabbed, so it’s not like you can avoid any and all pain, but to have somebody aware of those ideas and the fact that it’s not always comfortable and try to do their best to make it as comfortable as possible for you is a huge game changer,” Nembhard said.

Once Nembhard started going to women and non-binary people for their tattoos, they said they could never imagine going to a traditional tattoo shop again.

“Finding one artist or a couple of artists who do make you feel like you do know enough and that you do belong in the tattoo world, whatever that means, is really the only important thing,” Nembhard said. “There’s no points you’re winning in legitimacy for going to those traditional classic places. In fact, you might be missing out on real positive experiences.”

After spending years changing their appearance and trying to fit in, Jama said getting tattooed, specifically by a woman, was a major stepping stone in how they want to show up in the world.

“I feel like getting the tattoo on my face in particular was just kind of a ‘fuck you’ to that feeling almost,” Jama said. “I’m tired of feeling like I don’t belong, in a sense, and I just want to make my own way instead of fitting in somewhere. I would just kind of like to be my own person and fit within the bounds and the home that I create within myself.”