Andrew Beauchamp was living in Portland after graduating from the University of Oregon. When COVID hit he moved to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico for a little while. After going back to the U.S., and not liking the rain and cold weather, he decided he needed to move somewhere else. After a few trips, he landed in Mexico City, the capital of Mexico.

Beauchamp asked himself, “why not?”

It is not hard to love Mexico City.

In Andrew’s words, there are “a million bars, a million restaurants, a million museums.” There are endless amounts of activities and you can always find a fun and interesting thing to do.

The city itself is beautiful, with its tree-lined streets, architecture, and art and history. Of course, the food is amazing.

It doesn’t hurt that the city is “less expensive,” at least according to Beauchamp. For someone who is working on building a business like he is, the affordability comes in handy.

“I can pay myself considerably less money, re-invest that money back into the business and still have a much higher quality of life than I would have on something like that in the U.S., where I’d have to funnel more money out of the business to pay myself to just live,” Beauchamp said, CEO and co-founder of BS & Co., a marketing company, a business that he built with his roommate.

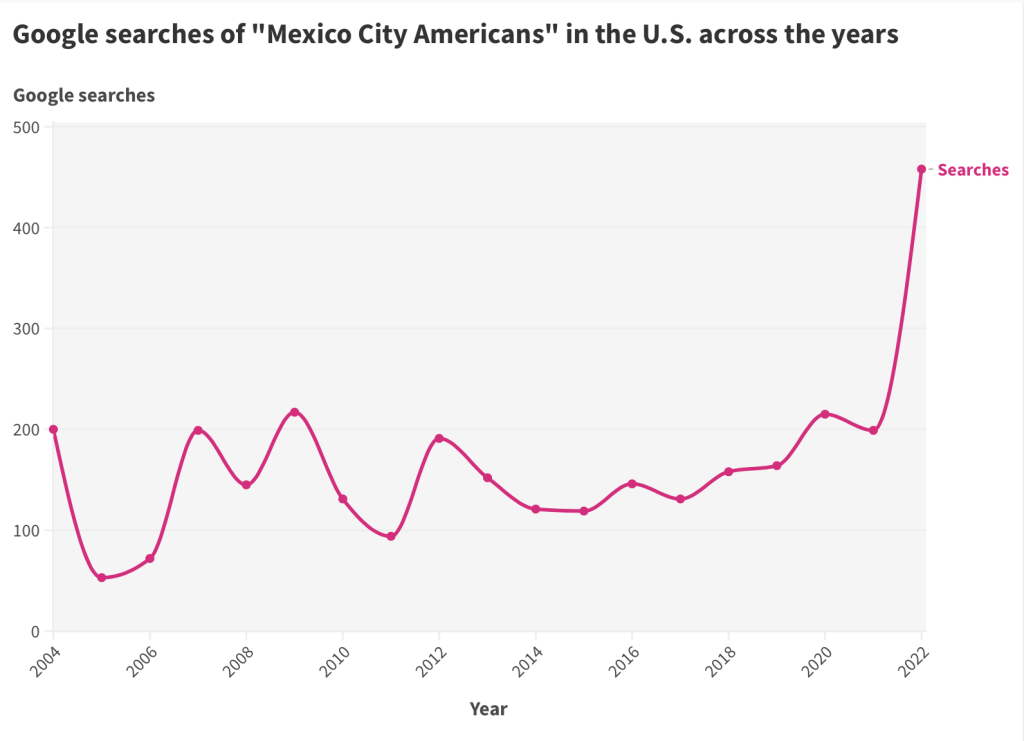

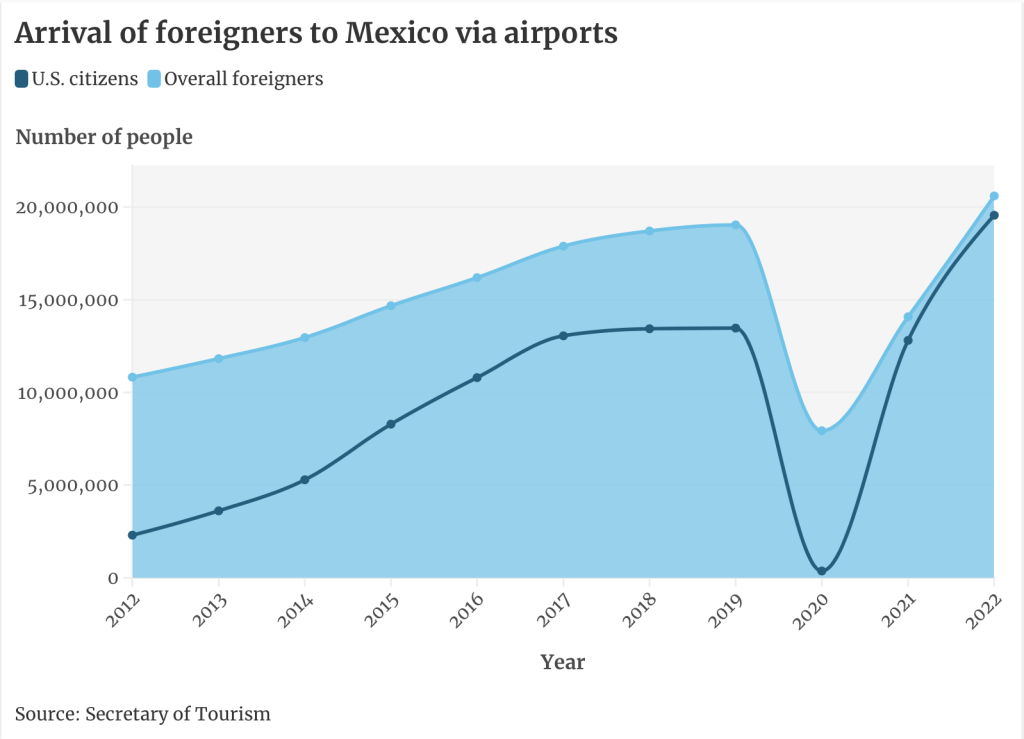

Beauchamp is part of a bigger movement of Americans and other Global North residents who are leaving their countries and moving to more affordable places like Costa Rica, Colombia and Mexico.

The movement started years ago, but it has taken off since the pandemic brought accessibility to remote jobs. If you don’t like where you are and have the opportunity to live anywhere, why not go somewhere else?

They call themselves expats but they are also known as “digital nomads.”

In Mexico, making this move is relatively easy, especially for those who are not seeking a residential permit. Mexico allows Americans to stay in the country visa-free for up to six months at a time, and because most digital nomads don’t work for Mexican companies and many are staying at places like Airbnb rentals, they can come and go without the need for permits or paperwork, a moved that the Mexican City government has encouraged with recent policies.

With the U.S. facing higher rent prices and higher inflation, and with salaries being slow to increase in comparison, many Americans are left struggling to pay their bills.

A CNBC survey found that 58% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, and about 70% feel stressed about finances.

The combination of the rising cost of living and the ability to work abroad makes Mexico City an attractive destination, at least for a few years while one saves money.

The problem? Some locals are not happy with the rapid influx of digital nomads. Their arrival, they said, brings the cost of living up, in what was already an expensive city.

The local discontent

Ilse Torres, a biology student at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM, in Spanish) says rent has increased significantly.

“A lot of people who rent near (my college campus), if they used to pay 3,000 pesos for a room now they pay 5,000 pesos,” said Torres, adding that 3,000 pesos for renting a room was already expensive for her.

Rent isn’t the only thing increasing in price.

Torres says that buying a kilo of tortillas in her neighborhood just outside of Mexico City costs about 20 pesos (or about 1 dollar), but in neighborhoods like Condesa, where digital nomads are settling in, it can cost five times more, with the marketing pitch that they are organic and hand made.

Carolina Garcia, an artist and recent graduate of Anahuac University, in greater Mexico City, says this can also be seen in neighborhoods other than Condesa or Roma, the two neighborhoods known to be popular among digital nomads.

“They are starting to go to other places that are pretty, pleasant, even safe to a certain point, but that are poor like Santa Maria,” Garcia said.

Santa Maria de Ribera is a lower-income neighborhood that is close to the historic center of Mexico City. Garcia spends a lot of time in the neighborhood with her boyfriend, who grew up there, but recent changes in the neighborhood have forced them to change their routine.

“It’s getting filled with restaurants, the elegant type, more expensive, hipster-like,” said Garcia. “There was a ramen restaurant that I really liked, but I don’t go anymore because they increased prices and now only Americans go there.”

Dr. David Navarrete Escobedo, with a Ph.D. in urbanism from the Planning Institute of Paris and a current professor at the University of Guanajuato in México, says there’s an inequality that is forming.

The arrival of the digital nomads “was suddenly massive, it was perceived more in the city and that was very different to everything that we had lived with the reception of foreign migrants in Mexico City, which has a long history,” said Navarrete Escobedo.

The arrival of the digital nomads was a wave too short and too abrupt for the city, he said, which was something locals felt as well.

“Two years into the pandemic and I wasn’t going into the city much, for almost a year I didn’t touch the center of the city. And suddenly when I came back I felt strange,” said Torres. “I felt strange in my own city because I am a small person in height, I have brown skin, I am the prototype for Mexicans to put it this way.” It was strange because she said she started to notice the Americans who were taller and went out in the streets wearing shorts and no shoes.

“I felt strange in my own city.”

Ilse Torres

In Latin America, not wearing shoes is considered rude and unhealthy. But although it is not uncommon for tourists and foreigners to break social norms, Garcia feels the social aspect of this issue runs deeper.

In much of media and global politics, the Global North is considered more socially liberal and a champion in public morality, something for developing countries to look up to, and Garcia feels that many digital nomads arrive carrying a superior attitude, with the idea that they have something to teach to the locals.

“I hate that they come here thinking they are, I feel like they put themselves on a moral pedestal,” Garcia said, citing examples such as LGBTQ issues or having an open romantic relationship. “They think that because they have developed ideas they are morally superior and with a greater knowledge, and there are others who (think) they have to come and to teach us something.”

Garcia also recalls a friend of hers who had dark skin and was dating an American, and Garcia felt the American girlfriend prided herself on having a dark skin boyfriend, fixating on his dark skin and un-American nationality.

Garcia also feels like the new arrivals can’t conceive Mexican culture as something other than exotic.

“So liberal and whatever, but they don’t want to accept that their presence and them staying here hurts the economy and displaces a lot of people,” said Garcia.

Americans are no strangers to the negative opinions of the locals.

“Everyone’s mad about all the gringos coming,” said Beauchamp on the topic.

The role of the government

With the arrival of digital nomads, the government was incentivized to collaborate with the private sector, changing the structure of the neighborhood.

In October 2022, UNESCO, Airbnb and the government of Mexico City partnered to promote the city as a destination for remote workers.

Airbnb says the partnership will aid in developing “curated” cultural experiences in neighborhoods with less tourism while providing information to make it easier for remote workers to stay in the country.

The partnership has been criticized by experts, who compared how other governments in cities that also have high volumes of tourism implemented restrictions on Airbnb and similar companies, unlike the government of Mexico City.

In London, for example, residents are restricted from renting their property short-term for more than 90 nights a year. Any other rent agreements have to be long-term unless planning permission was granted. Similarly in Paris, where housing is limited, you can only rent your apartment on Airbnb if it’s your primary residence and you are renting it for less than 120 days per year.

In the U.S., several cities are considering implementing restrictions on Airbnb and short-term rentals, following the increased interest in those rentals in a post-pandemic world.

Having a high number of spaces up for a short-term rental incentivizes those with multiple properties to rent out their spaces for an increased price, pushing out families or individuals who need housing.

Under this economic model, renting out residential places that are not your primary residence benefits those who own multiple properties, at the expense of those who are pushed outside the neighborhood.

“The (elites) also benefit from this gentrification because they have the financial capital to adapt the spaces and usually own the property, as well,” said Navarrete Escobedo. “So, does transnational gentrification communicate with national gentrification? Yes. They run almost parallel in some cases and have similar problems in that regard as well.”

Alexandra Dunnet, co-host of the podcast Gracias Por Participar, shared on Twitter how all her neighbors moved out, leaving her as the only permanent resident in the building. All the other apartments were turned into Airbnbs. In a Tweet, Dunnet shows the Airbnb listing for an apartment in her building. The podcast host says she pays 10,000 pesos or 550 dollars for her apartment, the listing she shared shows that same apartment building for 85,700 pesos or 4,700 dollars.

“The good thing is that rents were not going to skyrocket,” wrote Dunnet, sarcastically, tagging the Head of the Government of Mexico City Claudia Shein.

Talking about gentrification in general, Navarrete Escobedo mentioned how it goes beyond just moving somewhere else.

“The concept is the right to the city, the right to work in the city, to live close to where you work, to move within a neighborhood, to have family and affective ties in the neighborhood, to feel part of a community,” said Navarrete Escobedo. “So, living in the city, the right to the city in the long term is the one that erodes the most with gentrification.”

Navarrete Escobedo later said that if someone grows up in a central area, where people with a bigger economic power are starting to settle, they will most likely have to leave eventually, leaving behind relatives and personal stories.

But, is it gentrification?

Dr. Luis Alberto Salinas Arreortua, principal investigator of the Institute of Geography at UNAM says gentrification includes a dispute over urban space, those who have more economic and cultural wealth tend to prevail, displacing those with lower resources.

Solely with this definition, the current situation in Mexico City does seem to check all the boxes. But, Salinas Arreortua adds that gentrification is not caused by an individual simply moving in.

Salinas Arreortua says that in order to be gentrified, the neighborhood has to go through several changes, such as an investment of funds, which can be from the government or the private sector, the displacement of people, and the appropriation of space. “It’s not only that people with certain characteristics arrive. But one can identify, one can tell when a neighborhood starts transforming due to the use and of whom is appropriating the space.”

It doesn’t have to be the entire neighborhood, but it can be a smaller zone or a street.

There is no doubt that locals have felt an economic and social shift with the arrival of digital nomads, but in Mexico City, and in the neighborhoods of Roma and Condesa specifically, the gentrification can be traced far back.

Roma and Condesa were already expensive neighborhoods, at least by standards of what most of the city can afford. The neighborhood, known for its parks and architecture, was previously gentrified by Europeans and wealthy Mexicans.

“The first piece (is) that in the central area of Mexico City, where this phenomenon of the arrival of foreigners to work is taking place, it is an area that has an important patrimonial character. They are neighborhoods that were founded at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th,” said Navarrete Escobedo. “So they are built frames that have an aesthetic, let’s say, highly valued.”

La Condesa, for example, has historically been a residential neighborhood, which in the early 20th century it was a residential place for mostly the middle and upper class. In the 1970’s the neighborhood saw development, but it all stopped in 1985, when on September 19 a powerful earthquake shook the city, destroying several buildings across the city and killing thousands. La Condesa was particularly affected, and according to Oscar Adán Castillo Oropeza, a sociologist at the Autonomous University of the Estate of Mexico, the neighborhood saw a period of decay in the years that followed.

Some wealthy people left the neighborhood, and rents went down and Castillo Oropeza writes that families with fewer resources started moving in.

“The transformation process of the Roma and Condesa neighborhoods in those years is one of greater decline, due to the tertiarization process they experienced, as well as the social and structural changes generated by the departure of the population, loss of housing and decay of security,” wrote Castillo Oropeza.

But in the mid-1990s the central part of the city there was an investment in the development of the city, with the purpose of preserving cultural heritage and bringing back people to these neighborhoods.

It was around this time that Mexico started adopting neoliberal politics which caused a deep change in the country and the city. “Towards the 90s (there was an) increase or growth of businesses in (residential) areas,” said Salinas Arreortua. “Today it is very common to see either restaurants, clubs, or stores of well-known brands that opened their businesses here.”

With the investments of the public and private sectors, the neighborhood saw another big change.

“In terms of housing production, government authorities have allowed the construction of buildings on land previously intended for single-family homes and in places classified as having high heritage value. Thus, single-family homes have been displaced by multi-dwelling buildings,” writes Castillo Oropeza.

While the earthquake of 1985 had a big role in the social and economic changes in the center of Mexico City, the collaboration between the government and the private sector is what allowed the gentrification to take place.

But, why are Americans moving to Mexico City?

The Mexican Dream

“What’s is there not to like?” said Steve Kelly, a remote worker from Chicago. “The food is incredible; people are hospitable, they say hi to you when they pass by, they tell you ‘bon appetite’ at the tables; the produce is more organic, we’re able to get wonderful fruits and vegetables from local farmers; the weather is beautiful, year-round; full of culture; full of more of an of a laid back lifestyle with people who actually enjoy their life; work-life balance is more prominent here.”

Kelly’s situation is different from your stereotypical digital nomad, his wife is Mexican and they are choosing to raise their triplets in Mexico.

“I really just accepted it as my home for the next few years,” said Kelly.

Digital nomads usually cite the rising cost of living and a decrease in quality of life in the U.S. as a reason to leave.

With cheaper rents, and a better quality of life, moving to Mexico while working remotely in the U.S. is what many expats are calling the Mexican Dream.

“I am currently living in Mexico City and I am currently living the Mexican Dream,” said user Kristie Martin, @_kristiemartin, on a TikTok video. “Back then our parents used to go to the U.S. for a better quality of life and now I feel like I had to leave the U.S., a lot of people are leaving the U.S. to come to Mexico for a better quality of life,” she said.

Martin goes on to say that in California it’s so expensive “you don’t have time to enjoy life,” but that people in Mexico know how to enjoy life. “I’m not talking about money, I’m talking about the quality of life,” said Martin in her video.

Rent and food and services are cheaper in Mexico, plus 1 U.S. dollar equates to about 18 to 20 Mexican pesos, so if you earn in dollars, your dollar would sell for higher.

But salaries and incomes are smaller in Mexico, with the minimum wage in most of the country being 207.44 pesos per day or around 11.52 dollars per day.

In 2020, 43.9% of Mexicans lived in poverty, and 8.5% of Mexicans lived in extreme poverty, so for most Mexicans who earn in pesos, and live within the system, the Mexican Dream is nothing more than a dream.

Another common reason cited by digital nomads is security.

In her TikTok, Martin shares that she feels safer in Mexico. “I’m from Inglewood, California, it is not safer in California than Mexico”

But California is safer than Mexico.

The homicide mortality rate in 2021, which is calculated by the number of people killed per 100,000 residents, in Mexico City was 10.9, while in California the rate was 6.4 for that same year. Mexico City is both a state and a city, although California is much bigger than Mexico City. The rate in Mexico City does not include its metropolitan area. In the Estate of Mexico, where much of the metropolitan area is located, the rate is 18.

Several U.S. states have a much higher homicide mortality rate than California, with Mississippi (the highest one of all the 50 states) having a rate of 23.7, according to the CDC.

But in Mexico, the estate with the highest rate in 2021 was Zacatecas with a rate of 109, followed by Baja California with a rate of 86, and then by Colima with 82, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography.

The average rate of the U.S. is also smaller than Mexico’s, with the U.S. being 7.8 in 2020, which represented a 30% increase from 2019. In Mexico, the rate in 2020 was 29.

Yet, the murder rate alone is not enough to describe the insecurity in Mexico, with the country reaching 100,000 missing people in 2022, almost all going missing since the start of the War on Drugs.

To compare it, the U.S. has over 23,000 open missing persons cases.

Users in Martin’s TikTok pointed out in the comments, in English, that this dream and experience only works if you earn in dollars.

“If you have money every country is a dream,” said username @johngonzalez5353.

Martin is not the only one who has pointed out similar ideas.

In December of 2022 writer Jeffrey A. Tucker tweeted:

People responded differently to the tweet: some agreed, some pointed out Tucker probably only step into the rich neighborhoods, some simply laughed.

Besides the sense of security that wealthy neighborhoods might provide to digital nomads and the economic extent that the dollar and US salaries have over the Mexican peso, medical tourism has been a sizeable factor for many Americans going abroad, not only to Mexico.

For Americans seeking cheaper medicine or treatments, Mexico’s public or private practices are often a more accessible option. Patients can save an average of 40 to 65% in medical costs, according to Patients Beyond Borders, the same organization estimates that the market for medical tourism is growing at a rate between 15 and 25%, with most patients going to Mexico and Southeast and South Asia.

But while Americans feel safer and say to have a better quality of life, many locals are still not happy.

Kelley, who has a Mexican wife, Mexican kids (who he is trying to raise kids in Mexico) and who has Mexican friends, still hasn’t been able to escape the negative comments.

“You will get these negative comments like, ‘What are you doing in this country? Get out,’” said Kelley, who adds that that’s not how he wants to feel because his children were born here. “If you have an opportunity to live somewhere, why shouldn’t you be able to?”

Kelley also adds that he tries to be respectful and is working on improving his Spanish. “I try to be not like a rude arrogance like some of Americans might be or whatever the case,” he said.

“If you have an opportunity to live somewhere, why shouldn’t you be able to?”

Steve Kelley

Beauchamp, who used to live in Portland, understands the frustration, as he says people in Portland are angry about people from California moving in and causing prices to rise.

In his defense, he says he is not part of the “gringo bubble,” that is Americans who only interact with other Americans and make no attempts to speak Spanish, behavior that locals resent.

Beauchamp, who has his own business and currently employs Mexicans and other Latin American workers, believes that counts for something.

“Maybe I just tell myself this to make me feel better, but we also employ people here and are directly contributing to the economy, and we’re setting up our business to play everything by the books, and we’ll be paying taxes,” said Beauchamp.

When talking about gentrification in Mexico City, Salinas Arreortua remarks that it’s important to not fall into bias.

“When talking about digital nomads, especially foreign ones, we may be running the risk of racism, of a fear towards the other, towards the one who is not national,” said Salinas Arreortua.

Still, besides the occasional comments, Beauchamp and Kelley say they do have local friends and have positive experiences with their Mexican peers.

“For the most part people if you’re respectful, you’re interacting (and) you’re feeding money into the economy and being nice,” said Kelley.

The other side wants to build a wall, how is it different?

With many Mexicans going to social media to complain, some social media users have responded with the elephant in the room: how are Americans moving to Mexico different from the millions of Mexicans who emigrate to the U.S.?

It all comes back to status and money.

Digital nomads come to Mexico with job security and a salary that it’s usually enough to live comfortably. The Mexican government does not classify them as immigrants, because they have tourist visas and have more mobility than immigrants. And although some digital nomads consider themselves to be residents of the country, often they are not planning to completely immigrate to the country, but are here temporarily.

Beauchamp, for example, doesn’t know when exactly he will leave Mexico City but said he is likely to stay for a couple of years, but not for longer than 5 or 10 years.

On the other hand, although many Mexican immigrants have left the US in recent years, Mexicans in the U.S. are more likely to stay in the U.S. for a long period of time, compared to other immigrants, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Mexican immigrants are also more likely to live in poverty and less likely to have services like health insurance, compared to the general immigrant population in the U.S., marking a clear contrast with digital nomads.

Tourism vs. Immigration and the Gringo Bubble.

Garcia says that her problem with digital nomads is not that they are moving in, but that they are doing it off the books while staying in their “gringo bubbles,” as Beauchamp put it.

“Let them come but do it as a Mexican, get a Mexican job, that way I don’t have any problems,” said Garcia. “Come here and contribute to the economy here. Spend in pesos, that is, earn in pesos and spend in pesos.”

Mexico City is no stranger to foreigners settling in. Whether they are Spaniards that came after the Civil War, Lebanese during the 20 century, or simply other Latin Americans across the decades, Mexico City has always been a recipient of immigrants.

But a key point here, says Navarrete Escobedo, is the difference between a tourist and someone who is looking to settle.

Navarrete Escobedo says the effects of inflation in zones where digital nomads are staying like Roma or Condesa is clear. But, if in a year or two the expats decide to come back to their countries, the neighborhoods will have a gap.

But prices will not drop, he says.

“But prices are no longer going to go down, nor are rents going to go down,” says Navarrete Escobedo. “Then there will be a permanent effect for the city and it will generate more inequality and more discontent, which will not be counterproductive in the long term for the Mexican cities that are in this process.”

Navarrete Escobedo does not diminish the cultural richness that the foreign populations, the immigrants, have brought to the country historically, but he says their contributions have been different.

“They established permanently, they have integrated into society, have contributed to the construction of national identity,” said Navarrete Escobedo. “The conditions of this new profile of people are now different because, in the end, they are tourists. And a tourist does not live permanently, they do not permanently build a city.”

In the end, while individual people cannot gentrify, locals are looking for a solution to the rising cost of living in the city, a problem that lies within the responsibilities of the government.