How One Family’s Struggle Led to a Network of Thousands

It had been nine years, and Gary and Kathy Schilmoeller still didn’t have an answer.

Their son Matthew had always been different, but doctors insisted there was nothing wrong with the boy, who by now was all the way into elementary school. In fact, they said it was his parents that were the problem.

Doctors accused them of looking for symptoms where there were none, inventing problems that didn’t exist. “Having a typical child would be too boring for you,” Gary recalls one doctor saying.

But when Matt was 9 years old, someone working with him during a summer vacation period thought they saw him have a seizure. Because there were no child neurologists where they lived in Orono, Maine, they had to drive two hours south to Portland so that their son could get a CT scan, revealing he had a condition called agenesis of the corpus callosum. Gary and Kathy were relieved to finally have a diagnosis, but they had no idea what agenesis of the corpus callosum meant.

A diagnosis yields new struggles

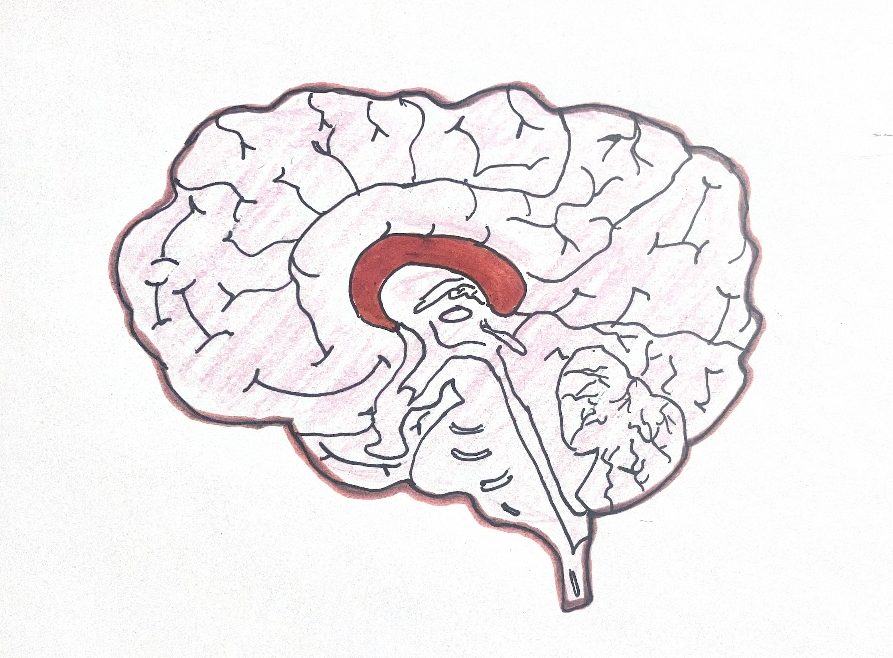

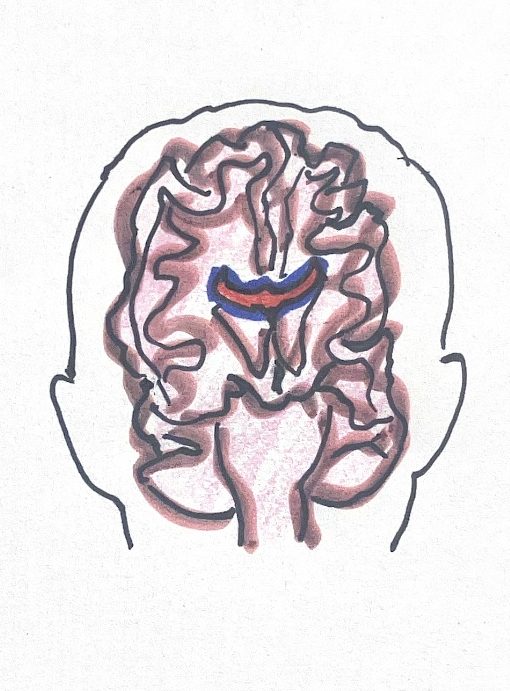

Agenesis of the corpus callosum, or ACC, is a rare mental disability about which little was known before the 1980s, when MRIs and CT scans became more accessible. It means that the corpus callosum, the collection of nerve fibers that connect the two hemispheres of the brain, is either partially or completely missing. But it was hard to know what this meant for their son.

After Matt’s diagnosis, Gary and Kathy asked the doctor all the key questions — “what should we do, where are the books, point us in the right direction,” — but the response from the doctor was simply, “I don’t know anything to tell you, except just keep doing whatever you’re doing.”

Dr. Elliot Sherr, a child neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, notes that ACC encompasses a diversity of conditions, and has become more recognized as modern imaging techniques like MRIs and CT scans become more common. Individuals with ACC often struggle cognitively and socially, which Dr. Sherr says needs more attention. “People tend to write off their other challenges, and therefore they struggle,” Dr. Sherr says.

highlighted in the middle

How mild or severe Matt’s case was could not be known, in part because of how wide-ranging the severity of the disability is, and in part because of how little was known about it at that time. Gary and Kathy found themselves having to constantly explain the condition to people, even within the disability community.

“It was a struggle,” Kathy recounts. She and Gary were forced to battle the school in order to advocate for Matt, which was still didn’t take his disability seriously.

At one point Kathy heard about a soap opera with a character that had ACC, and despite not being a soap opera person, began watching the show. “That was the first time that I had seen something beyond Matthew’s information about ACC. So it was a confirmation that it existed,” she says. “I kept taping the show, hoping there would be some little glimmer of information.”

The network is formed

Eventually, Gary and Kathy did find support. At a parent group that they were involved in, they were getting lunch when they overheard another couple talking about their son with similar conditions to Matt. “I plopped my tray down at their table,” Kathy says. “Didn’t know them, hand’t meant them yet. I just blurted our, ‘What’s your son’s diagnosis?’ And they said it was ACC.”

The couples got together for a weekend to exchange notes and discuss the commonalities and differences between their kids. This was the moment, Kathy said, when things changed — their ability to connect with another family had helped where medical professionals had not. “I thought, okay, this is how we have to go. We have to try out best to connect with other families, start comparing notes, and then maybe we can gradually start to build information.”

This way other families would be in a better position than Kathy’s family had been in. “They wouldn’t have to go through the turmoil that we had been going through for thirteen years.”

Gary and Kathy’s information was placed in a newsletter, which said the couple was looking for families members of people with ACC. This led to the creation of the ACC Network. “Then the phone calls started coming in,” Kathy says. She says she had no idea at that point how many families there might be — it could be no more than a handful of people. “But it turned out to be a lot more than that.”

Calls started coming in at all times of day from all over the world. Gary recounts a caller from South Africa calling at 4:00 in the morning, desperate for information.

Kathy, who took most of the calls for the ACC Network, began to realize just how important that first contact was. “Many of these people were in the same position that we had been in. They didn’t know anybody with ACC. They weren’t getting the kind of information that was helpful for them in dealing with the day-to-day issues that came up,” Kathy says. “I kind of saw that as the main thing that I could do, was be that first person, so they didn’t feel alone, so they didn’t feel like they were making things up.”

Gary, who taught full-time at the University of Maine, brought the network on campus and began running it through the university, setting up offices where he and Kathy could print newsletters, send out research surveys, and take calls. Gary’s office was adjacent to Kathy’s, and he would often overhear the phone calls she had with other people desperate for information.

“At some point in that phone call, I would hear this burst of laughter from Kathy, and I would know that she and the person speaking with her had met,” Gary says. The other person had finally made some sort of breakthrough, and a bond was formed.

Sarah’s story

One of the people Kathy Schilmoeller spoke with in the early days was a woman named Sarah Barnes, whose daughter Meredith has ACC. Sarah is a journalist-turned-author, and wrote about her experiences with her daughter in her memoir, Meredith and Me.

After Meredith’s diagnosis, Sarah found herself in a similar predicament to the Schilmoellers, and felt there was nowhere to turn. “It was devastating,” Sarah says. “I just couldn’t even talk, I didn’t even know what to think. And I couldn’t find a lot of information on it. So that was frightening.”

But after looking her daughter’s condition up online — at a time when the Internet was still in its infancy — Sarah did find something. It was the night she got the call from the neurologist about Meredith’s diagnosis, and she felt panicked, devastated, and lost. “I got exactly one hit — which was Gary and Kathy Schilmoeller,” Sarah remembers. “So I got in touch with them right away.” Sarah was involved with the ACC Network in the beginning, corresponding with Gary and Kathy and even doing their newsletter.

“They were without a doubt the pioneers in bringing attention to ACC and its research and removing stigmas,” Sarah says. She was stunned at how many parents were involved in the Schilmoeller’s research, and excited to be a part of it. One summer she even visited them in Maine, the first family of a child with ACC she had met.

“The scariest moment was definitely the diagnosis,” Sarah says. “It was devastating; I just couldn’t even talk. I didn’t even know what to think. And I couldn’t find a lot of information on it. So that was frightening.” Sarah’s biggest fear in the beginning, she recounts, was what Meredith’s future looked like. “The first thing my husband and I thought was, who’s going to take care of Meredith after we’re gone? Definitely our first thought. And we are still trying to find an answer.”

Gary Schilmoeller shares similar concerns about his son Matt. “One of my biggest fears is, who’s gonna do that when I’m not capable of doing that, or when I’ve died?” Gary says. “And I face that because I’m past seventy-five, and I’m not going to be able to do this indefinitely. And yet, there’s no system in place.”

Systemic challenges

Gary says that while people with acquired brain injuries like concussions are eligible for state resources, people with congenital brain anomalies — like ACC — are not. Matt was not able to get Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) on the basis of his ACC diagnosis itself, only receiving these benefits after a neuropsychologist diagnosed his inability to sustain attention.

As Gary points out, disabilities like autism are covered under SSDI, but ACC is not. “Children who had ACC would sometimes find out if someone would add the label of ‘autism,’ their child would suddenly be eligible for services when nothing had changed with the child,” Gary says, noting that many individuals with ACC show symptoms that parallel autism diagnoses. “That’s a thing that was very frustrating for us.”

| 200 million | Nerve fibers in the corpus callosum. |

| 1 in 4,000 | Individuals with a disorder of the corpus callosum. |

| 12th to 16th | Week of pregnancy when the corpus callosum begins functioning in the typical infant brain. |

| 5th to 16th | Week of pregnancy when disruptions to the corpus callosum generally occur. |

| 12 years | Age when the corpus collapse functions as it will in adulthood. This is when the corpus callosum becomes increasingly functional, and children with ACC appear to fall behind. |

Sarah, who lives in Texas, has run into similar challenges obtaining financial support. “Some states are much more liberal in terms of their view of how this works, and some states just really don’t care,” Sarah says. “You may be able to find groups who can help you, but they can’t help with the financial part of it, and that’s frankly what a lot of parents need.”

Leaving the network

The ACC Network eventually grew to a point that Gary and Kathy could not sustain on their own. “I knew I was in over my head at that time. I couldn’t keep running the network, advocating for Matthew, and dealing with all of this,” Kathy says. She knew their mission required more resources than she and Gary could provide on their own, especially as the phone calls from desperate families kept coming — on weekends, evenings, early mornings, even the middle of the night.

They were both involved in the formation of a new organization, the National Organization for Disorders of the Corpus Callosum (NODCC), and were hopeful that the group would maintain what they felt were some of the most important aspects of their network: connecting families to one another, the person-to-person contact, the phone calls.

While Kathy notes that the organization was doing many of the things they had hoped for, their visions did not entirely align.

“From my perspective, what ended up happening is that the people involved had a different vision that they wanted to pursue,” Kathy says. It became difficult for Kathy, who had worked on the ACC Network for the better part of twenty years at this point, to continue advocating for some of the features they had implemented. In the end, Gary and Kathy decided to step away.

Losing the dream

Their son Matt is 46 now and living in his own apartment, but Gary and Kathy are still intimately involved in his life. Gary, now seven years into retirement, says he hasn’t so much retired as switched jobs — becoming Matt’s case manager, helping him navigate bureaucracies, making sure he is able to live independently in his own apartment.

As for Meredith, she is 25 now, and, according to Sarah, doing well for herself. “Meredith is the least concerned with any of it, I mean she’s really happy,” Sarah says. “She is very empathetic. She’ll walk into a room, and whoever needs the most help is where she’s gonna go to first.”

This doesn’t mean it hasn’t been a learning process for Sarah. “The biggest thing I went through was, you lose the dream,” She says. “You dream about this baby, what she’s gonna be like, what she’s gonna become, and that is immediately lost when you get the diagnosis. And so it’s a grieving cycle; it’s grief, it’s losing what you thought you had. And you realize you’re on a different road, and you make different types of friends, and so that’s what happens.”

One of the things Kathy learned early on was that Matt was her teacher, not the other way around. “Through the experience of being his mother and advocating for him I was learning, where my edges were, where I needed to expand,” she says.

For other parents going through similar experiences, facing similar uncertainties, Kathy offers hope for the future.

“I would say try, if you can, to stay open to possibilities that you can’t even imagine.”